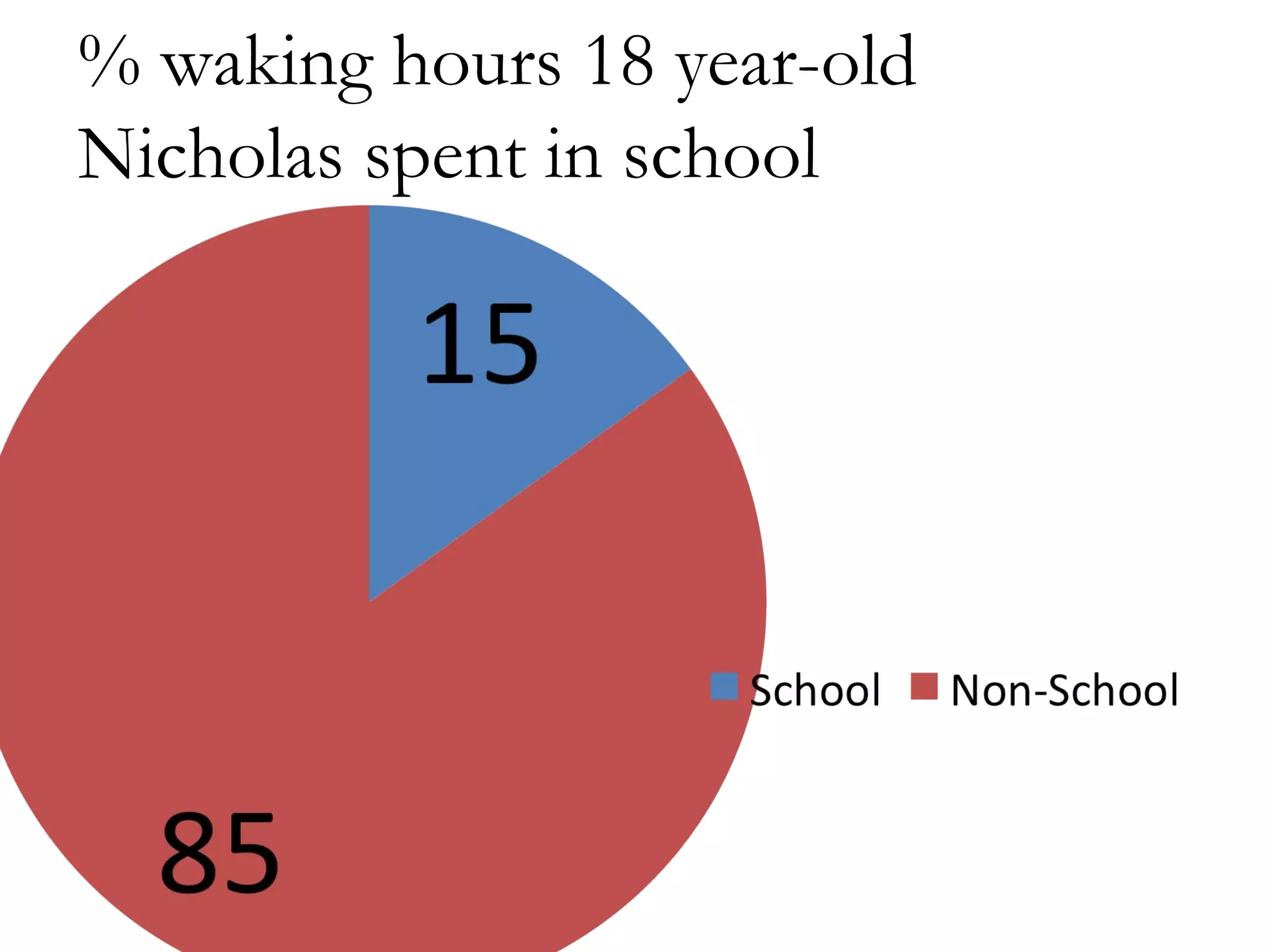

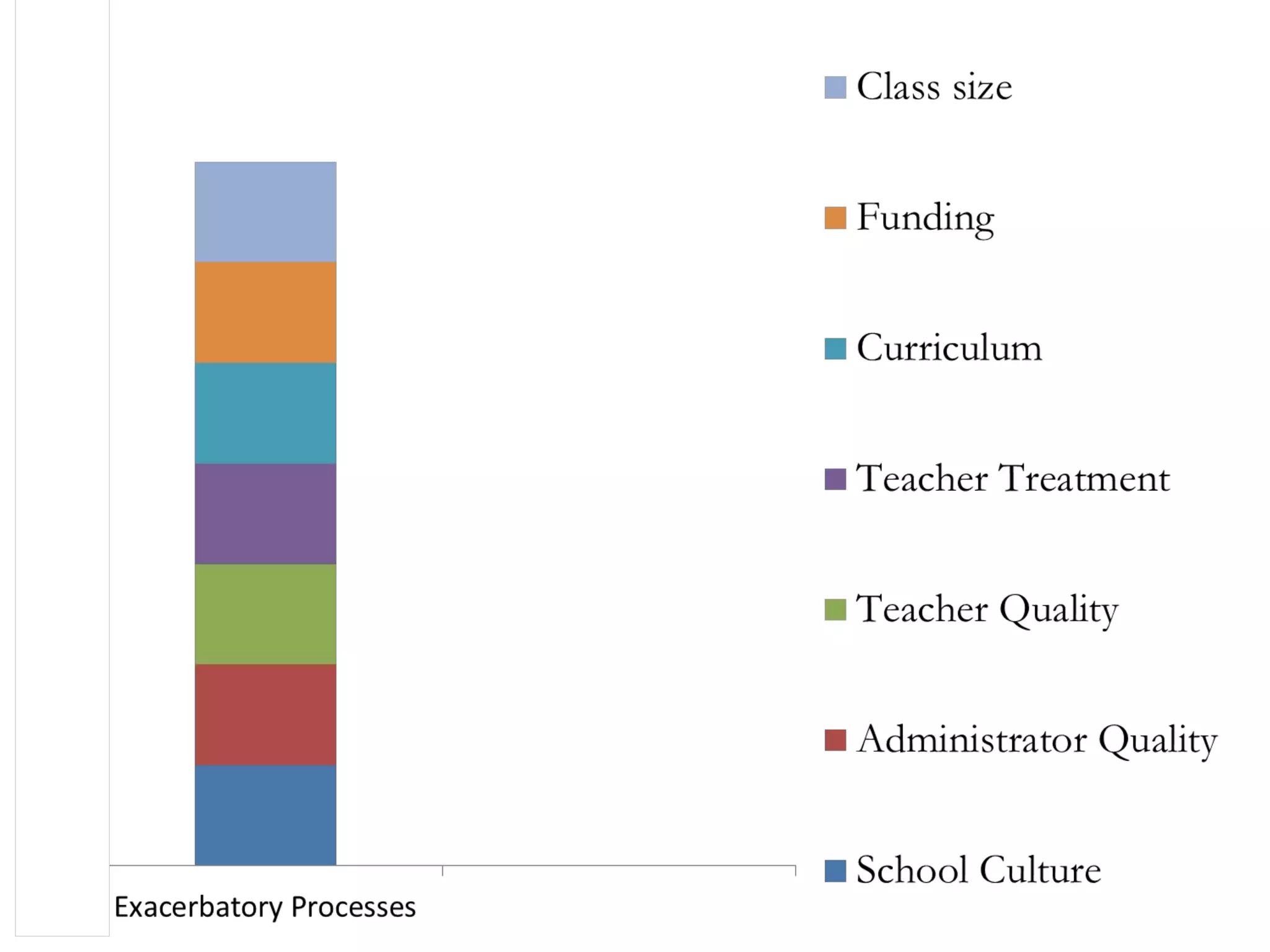

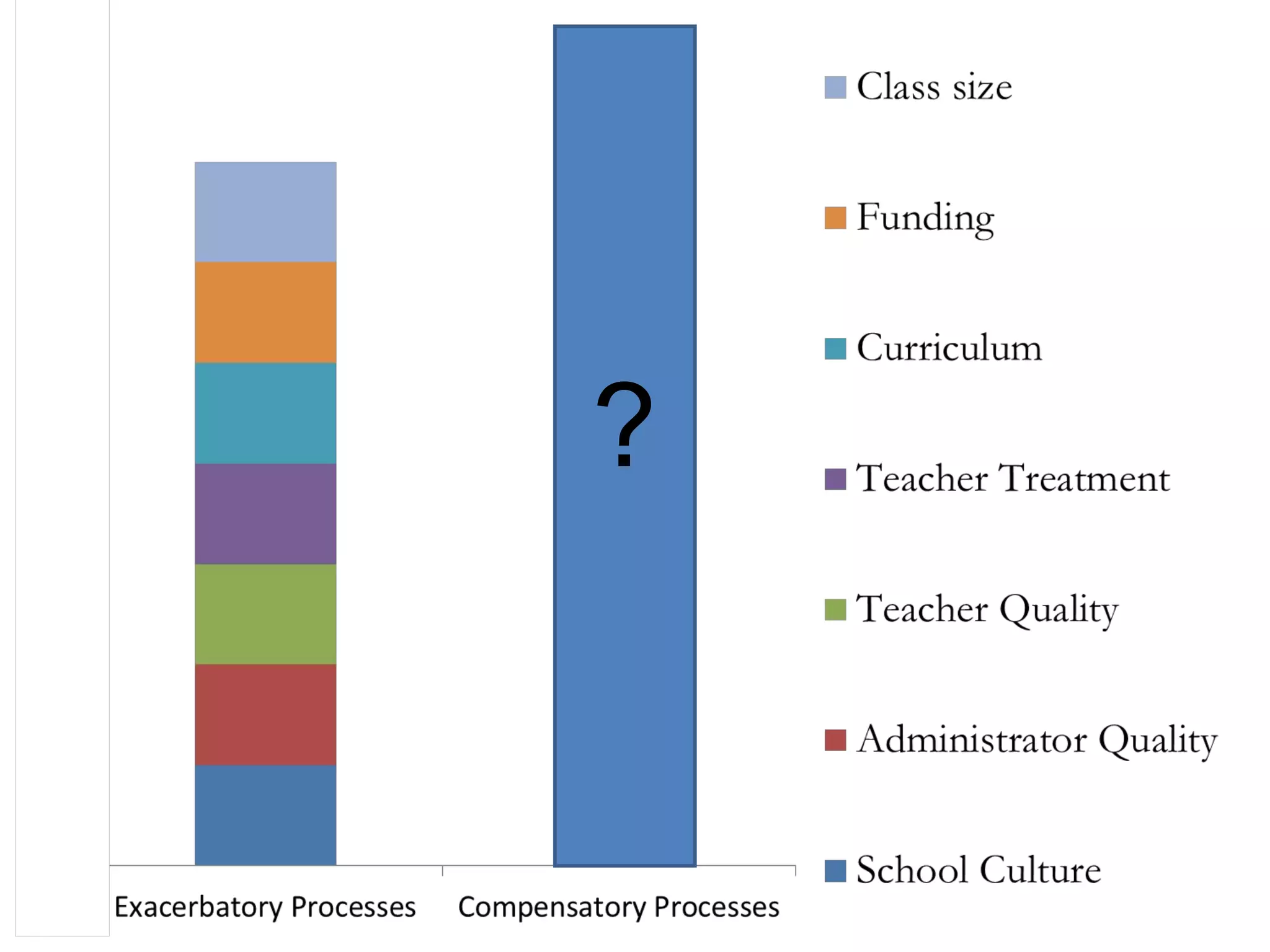

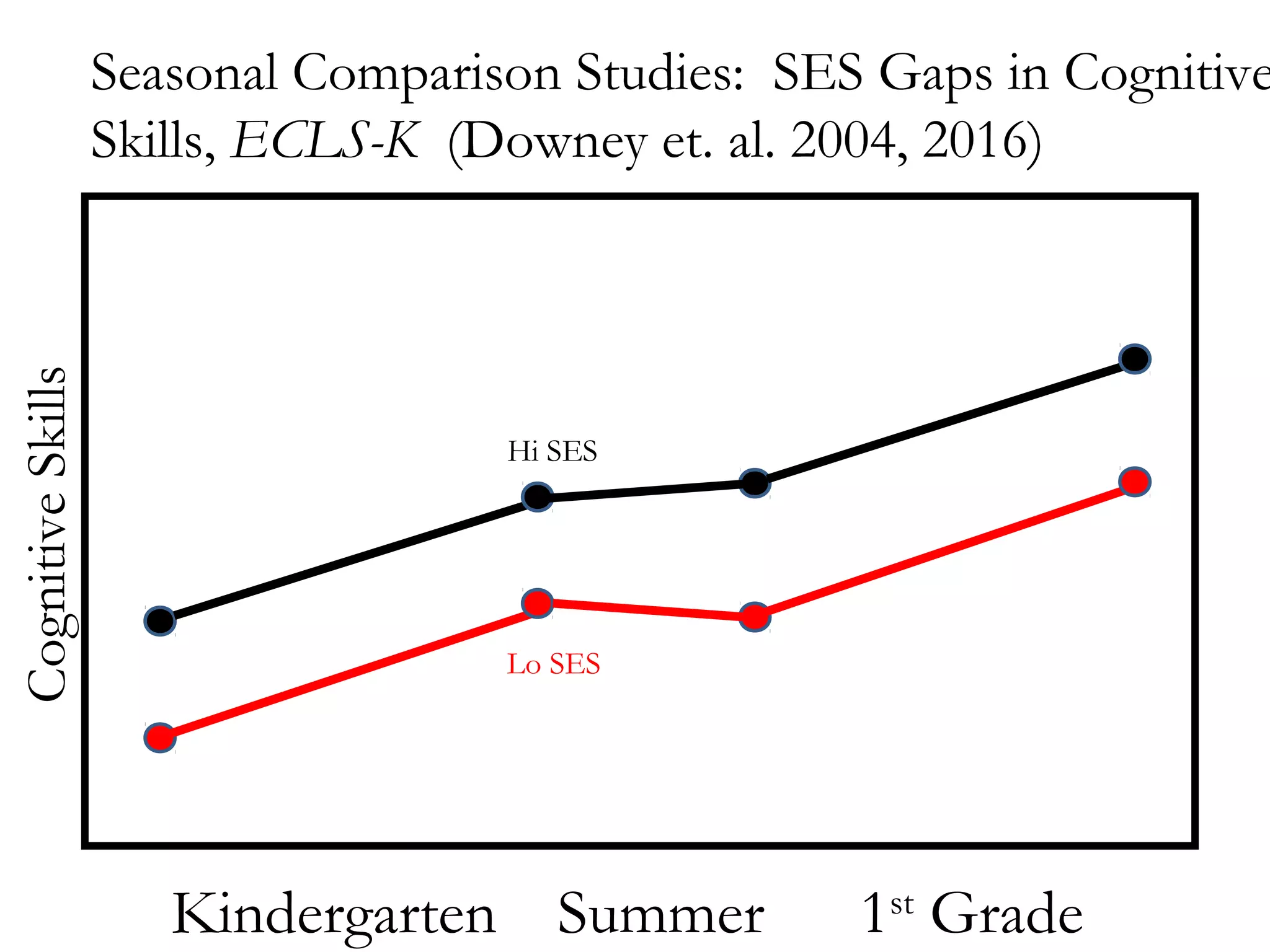

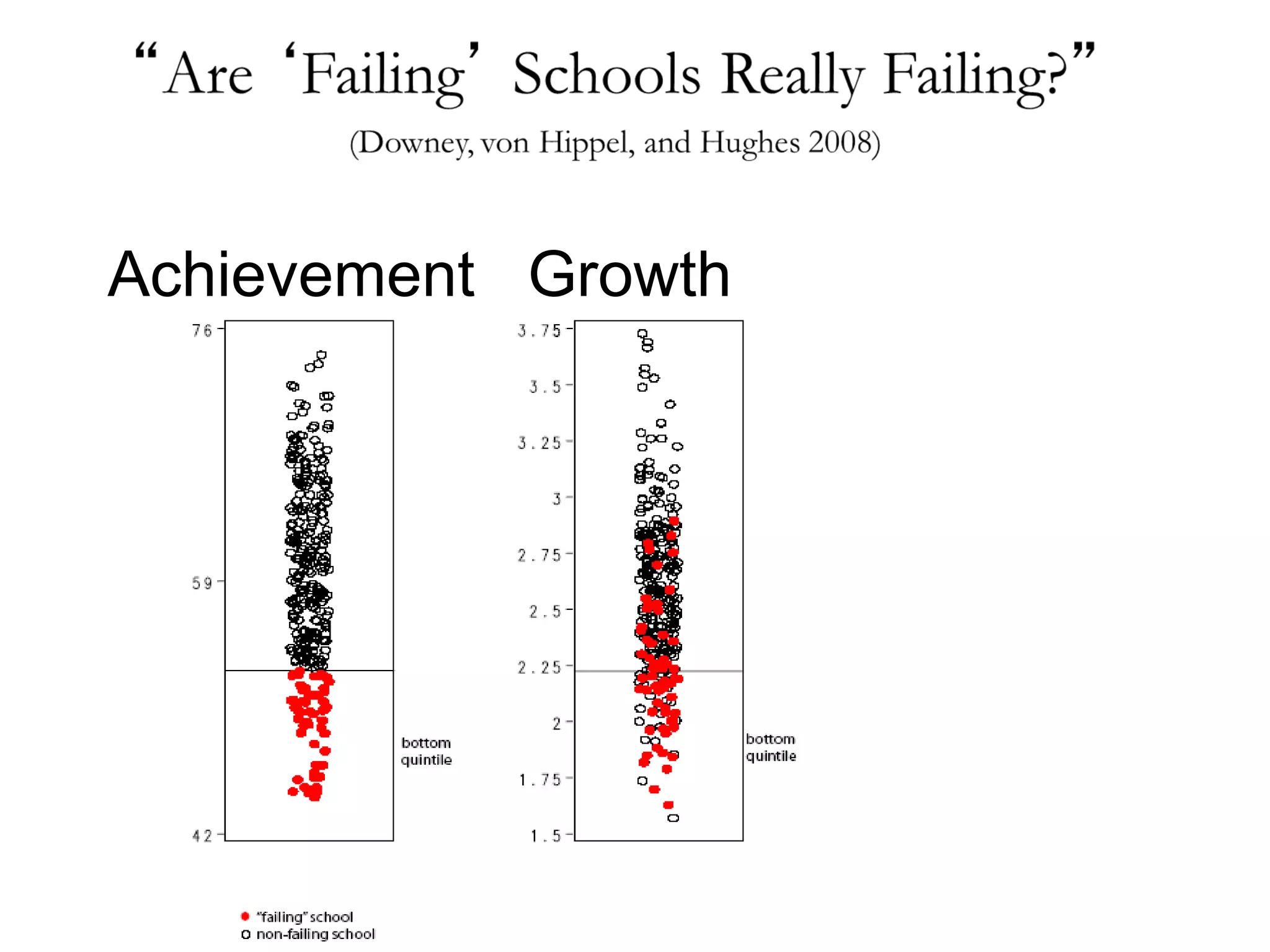

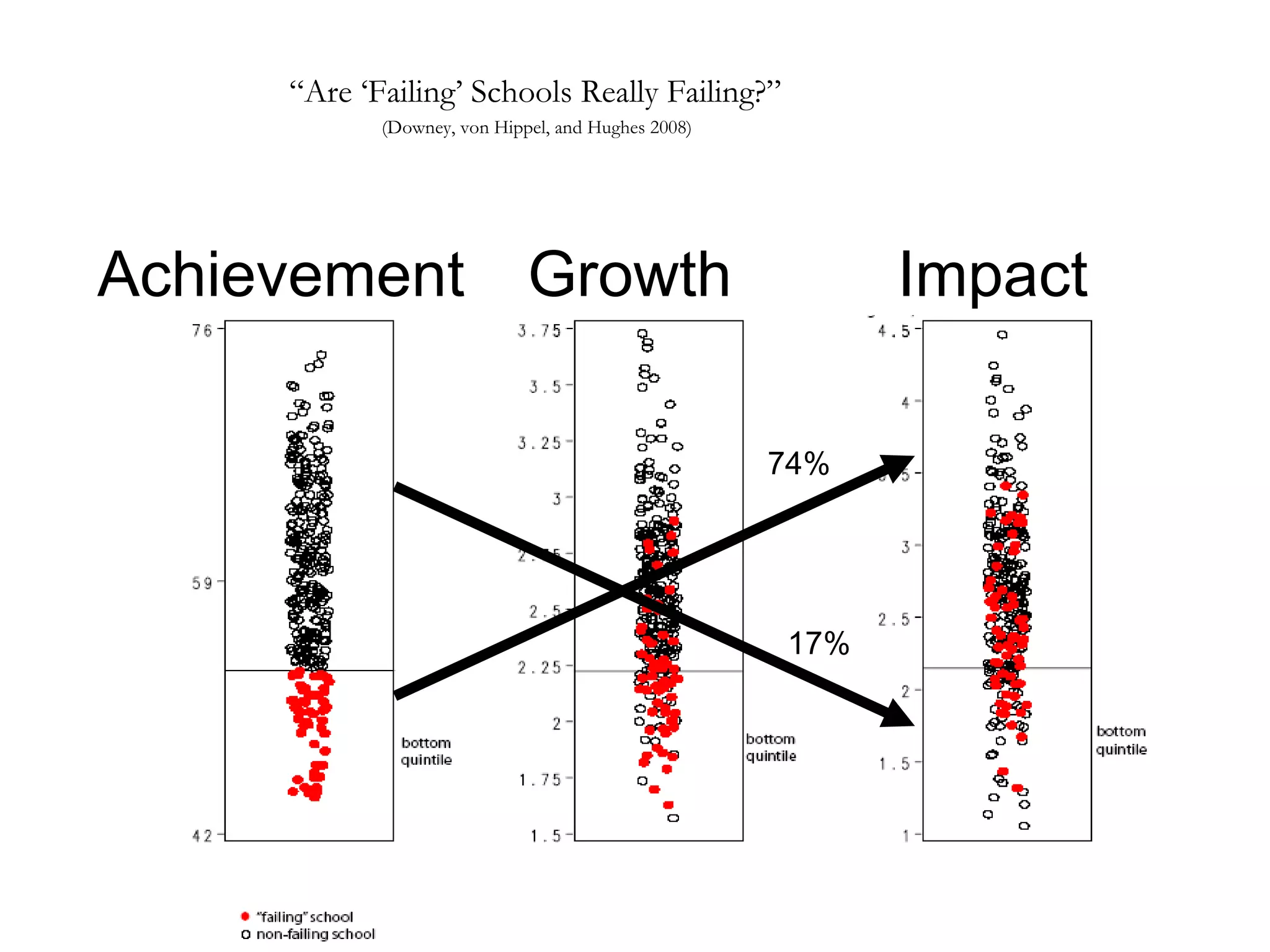

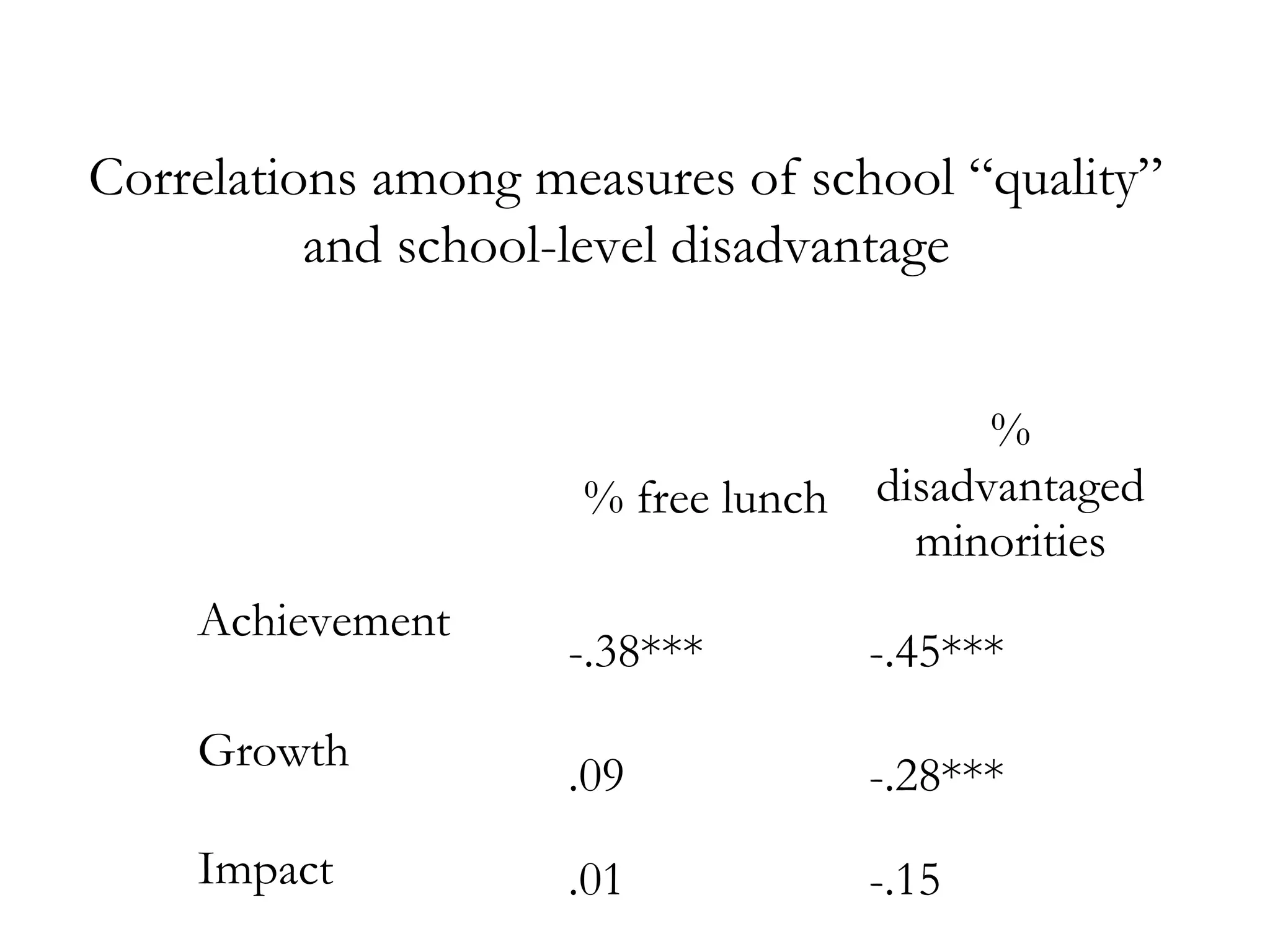

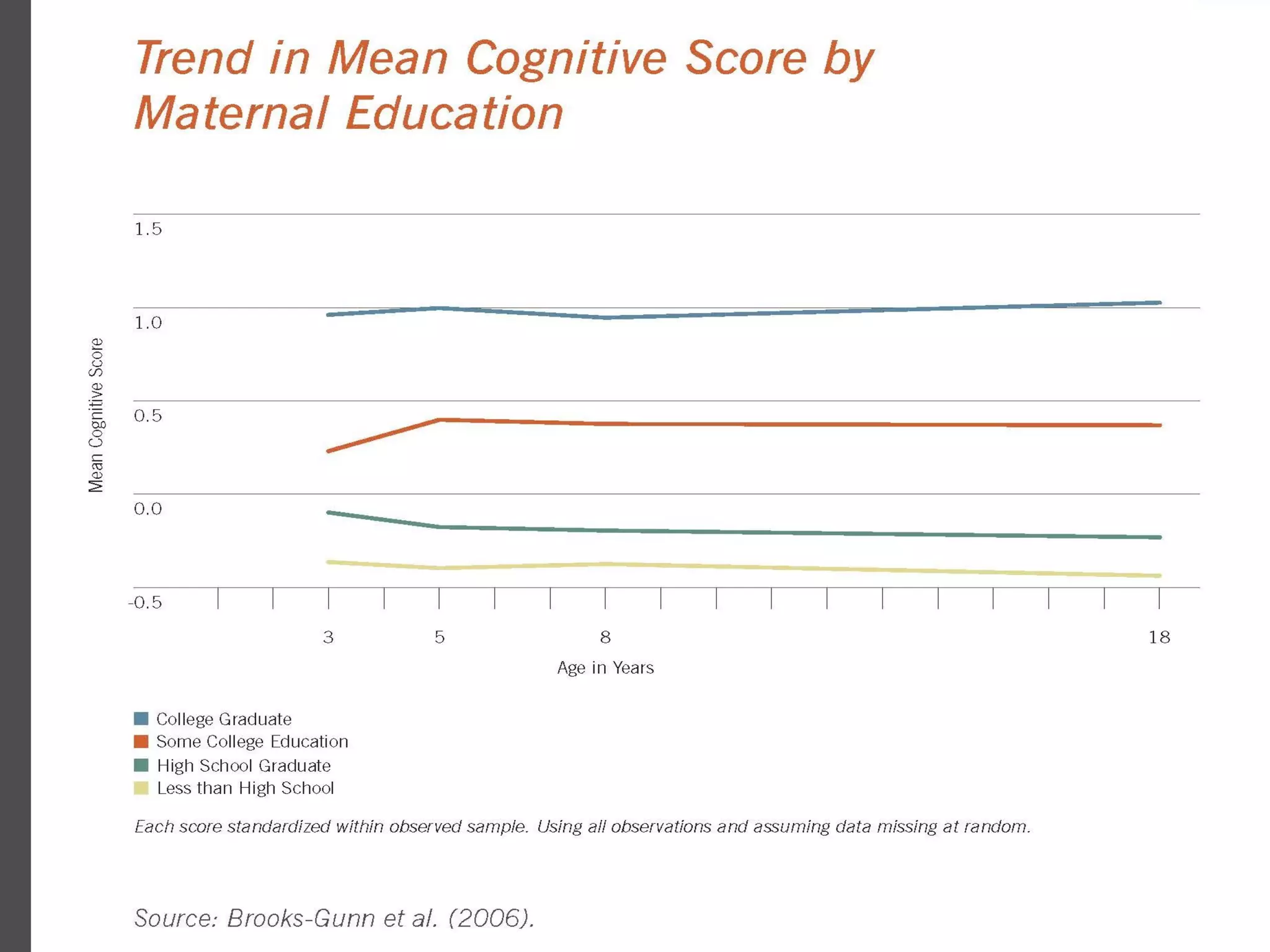

The document discusses the insights gained from seasonal comparison research regarding the relationship between schools and socioeconomic inequality, challenging the traditional narrative that schools exacerbate disparities. It highlights the limitations of traditional school-based research in isolating educational effects and emphasizes the need for broader social reforms to improve educational outcomes, particularly for disadvantaged students. The author argues that improved school environments alone are insufficient; systemic changes are necessary to address the root causes of achievement gaps.