This document discusses the role that families can play in supporting children as lifelong learners. It argues that the family environment provides a supportive learning environment that develops many of the key competencies for lifelong learning, such as the ability to pursue interests, solve problems creatively, and learn from natural experiences and conversations. However, it acknowledges that socioeconomic factors can impact parental involvement. While policies aim to engage all parents, some families remain "hard to reach." Overall attainment is determined by complex interactions between children, their families, peers, communities and schools.

![‘…Each person involved is contributing and sharing information, expertise

and ultimately the responsibility for actions and decisions. Thus accountability

belongs to all [and] all involved stand to gain from a productive discourse on

behalf of children…’ (Wolfendale, 1992:3)

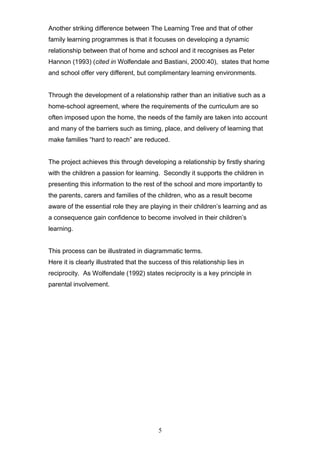

This case study is a retrospective analysis of The Learning Tree project.

Through firstly an exploration of research related to parental involvement and

6

School

Staff

Parents

and

Carers

Pupils

The

Learning

Tree

School

Council](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bb1be4cd-243e-4fcc-b4ff-f5c7bf6819e1-160717140320/85/Vibrant-Schools-Project-The-Learning-Tree-6-320.jpg)

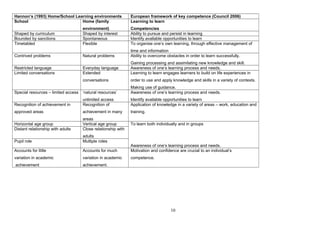

![Qualitative data from Parents at Nythe Primary School

2008

Power relationship

(Reciprocity)

Learning environment 3rd

space

(Ready, will and able to learn)

Learning dispositions

4 R’s

“I would just be doing the house work or shopping and my

daughter would be in bed watching Saturday TV, learning tree

gives us quality time with our children.”

a learning opportunity where both

adult and child can focus on learning

together without distractions of home.

“Learning tree is his time [father who works shifts] with the

children and I get to have a bit of space for myself.”

A learning opportunity offered at a

time when a father can be attentive

and children can develop as effective

partners in learning.

“It is a great way to learn together, we usually pull it apart and

put it back together again several times to see if we can do it

better. There’s usually a trip to the library like when we did the

bird feeders we put it up and then wanted to find out about the

birds that were coming into the garden.”

The environment created makes

people feel positive about learning.

Resilient –curious, determined,

flexible, observant.

Resourceful – questioning, playful

Reflective – methodical,

opportunistic.

Reciprocity – collaborative,

imitative, open to feedback

“We usually take it to Grandparents in the afternoon; it’s a

great stimulus for talk that would usually be quite mundane.”

Intergenerational

Developing a close relationship with

adults

Extending learning opportunity

beyond the classroom and beyond

the 3rd

space created by family

learning activity

Reflective – giving children

opportunity to develop a

philosophy about their learning, to

become self knowing.

“The children get to know how to do it and show us what to

do.”

Role reversal giving children

confidence and adults opportunity to

recognise/respect their child’s learning

and heighten their expectations

Reciprocity – collaborative

learning partnership

Develop strategic awareness – a

toolkit of strategies that they can

share.

“You’re never too old to learn.” said one granddad.” Intergenerational. Opportunity to

model life long learning.

Vertical age groups are made to feel

welcome in school and seen in school

by children and adults.

Creation of a learning community

“Sometimes I haven’t got a clue, I give it a go and I get it

wrong, we’re showing children that we are willing to learn and

show them that we can mistakes to.”

Equalising the power imbalance

To gain respect from children through

not always knowing the right answer.

A learning environment where you

can make mistakes and not be

judged.

Resilient – face challenges but

persevere.

“My son loves it when I go into his class” Increasing parental capacity for

involvement – both child and parent

feel confident to participate in learning

Adults welcomed into learning

community.

Reflective – create a feeling of

serendipity

“They see us all getting on and they know we talk to each other

so they have to think about how they behave because we’ll find

out what they’ve been up to when we all meet up again!”

Developing a collective responsibility

that is non judgemental or competitive.

Opportunity to model expectations,

values and beliefs and to relate to

other experiences of parenting.

Collaborative working

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bb1be4cd-243e-4fcc-b4ff-f5c7bf6819e1-160717140320/85/Vibrant-Schools-Project-The-Learning-Tree-40-320.jpg)

![References

45

Abbott J.A. 1999 The Child Is Father of

the Man: How Humans

Learn and Why

Network Educational Press

Ltd

Banbury, M. 2005 Special Relationships

How families learn

together

NIACE,Leicester

Bastiani J 2000 ‘I know it works...’ in

Wolfendale S. and

Bastiani J. eds. The

Contribution of Parents

to School Effectiveness

London

David Fulton Publishers

pp.19-36

Bateson B. 2000 ‘Inspire’, in Wolfendale

S. and Bastiani J. eds.

The Contribution of

Parents to School

Effectiveness

London

David Fulton Publishers

pp.52-68

Beckford M. 2008 Just 2pc of early years

primary school teachers

male

Telegraph 7th

August

[Online] available from

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/n

ews [accessed 14.08.08]

Campaign For

Learning

2008 Campaign For Learning

publications

[online] available from

http://www.campaign-for-

learning.org.uk/[accessed

28.08.08]

Claxton, G. 2002 Building Learning

Power

TLO, Bristol

Claxton, G. et al 2005 BLP in Action TLO, Bristol

Claxton G. 2001 Wise Up Network Educational Press,

Stafford

Claxton G. 2006 Expanding the Capacity

to Learn: A new end for

education

Opening keynote address

British Educational Research

Association Annual

conference.

Coleman P. 1998 Parent, Student and

Teacher Collaboration

The power of Three

Thousand Oaks, California

Corwin Press,Inc.

Das Gupta P. and

Richardson K.

1995 Children’s Cognitive

and Language

Development

Blackwells

Open University

Deakin Crick R. et

al

2004

Developing an Effective

Lifelong

Learning Inventory: the

ELLI Project

University of Bristol](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bb1be4cd-243e-4fcc-b4ff-f5c7bf6819e1-160717140320/85/Vibrant-Schools-Project-The-Learning-Tree-45-320.jpg)

![46

Desforges C.

Abouchaar A.

2003 The Impact of Parental

Involvement, Parental

Support and Family

Education on Pupil

Achievement and

Adjustment:

A Literature Review

Department for Education and

Skills

Research Report RR433

European

Commission

2006 RECOMMENDATION OF

THE EUROPEAN

PARLIAMENT AND OF

THE COUNCIL

on key competences for

lifelong learning

[online] available from

http://ec.europa.eu/education/lif

elong-learning-

policy/doc42_en.htm

[accessed 28.08.08]

Every Child Matters 2004 Every Child Matters DfES

publications

[online] available from

http://www.everychildmatters

.gov.uk/ [accessed 28.08.08]

Every Parent Matters 2007 DfES Publications

LKAW/2007

(Forward Johnson)

[online] available from

http://www.teachernet.gov.u

k/ [accessed 28.08.08]

Green L. 1970 Parents and Teachers

Partners or Rivals?

London George Allen and

Unwin Ltd.

Haggart, J. 2000 Learning Legacies

A Guide to Family

Learning

NIACE, Leicester

Mc Beath 2000 ‘New Coalitions for

promoting School

Effectiveness’ in

Wolfendale S. and

Bastiani J. eds. The

Contribution of Parents to

School Effectiveness

London

David Fulton Publishers pp.37-

51

Pahl K .and Kelly S

(p91|)

2005 Family literacy as a third

space between

home and school: some

case studies of

practice

Blackwell Publishing, Oxford

Smith S. 2007 Evaluation feedback from

Help Your Child to

Succeed course Devizes

Strong Children Project

Smith S. 2008 The Learning Tree Family

Learning project

[online] available from

www.learning-tree.org.uk

[accessed 28.08.08]

Smith S. 2007 ‘The Learning Tree

bringing family learning to

life Wiltshire

Early Years Magazine 2007.

Wiltshire County Council

University or Warwick

Kings College London

2007 Parent Support Advisor

Pilot: First interim report

from the evaluation

[online] available from

http://www.tda.gov.uk

[accessed 1.3.2008]

Wolfendale S. 1992 Empowering Parents and

Teachers Working for

children

London, Cassell

Wolfendale S. and

Bastiani J. eds.

2000 The Contribution of

Parents to School

Effectiveness

London

David Fulton Publishers

Wolfendale S. 2000 ‘Effective Schools for the

future: incorporating the

parental and family

dimension.’ in

Wolfendale S. and

Bastiani J. eds. The

Contribution of Parents to

School Effectiveness

London

David Fulton Publishers pp.1-

18

Wood R. 2007 Report on Enquiry Walk Supplied by Nythe Primary](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bb1be4cd-243e-4fcc-b4ff-f5c7bf6819e1-160717140320/85/Vibrant-Schools-Project-The-Learning-Tree-46-320.jpg)