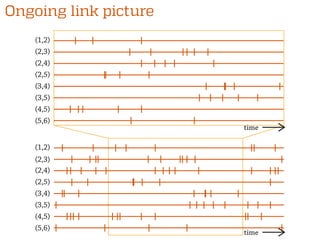

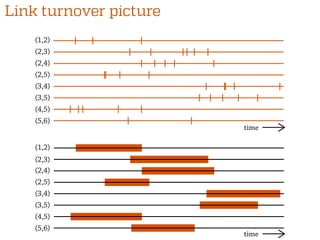

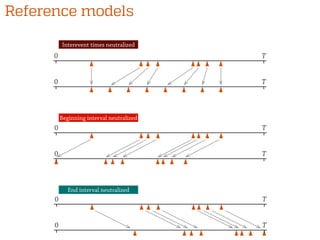

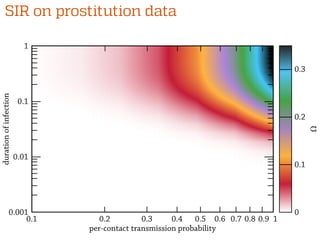

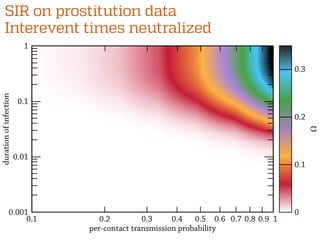

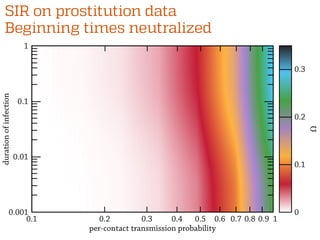

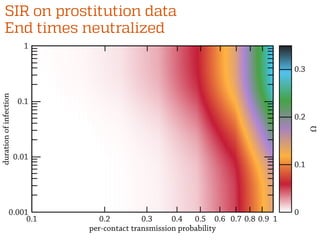

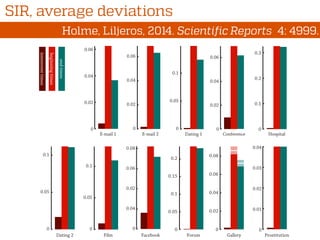

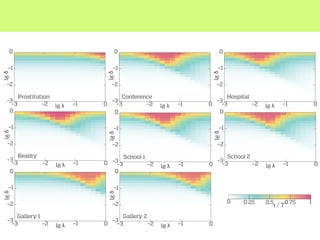

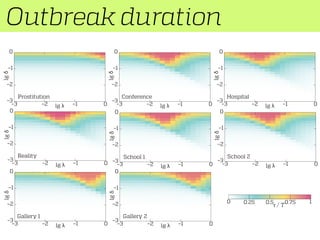

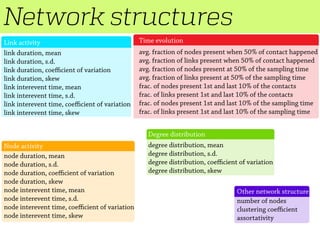

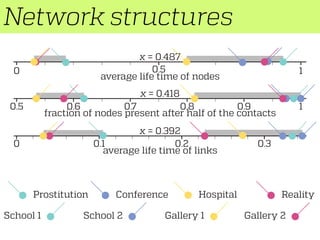

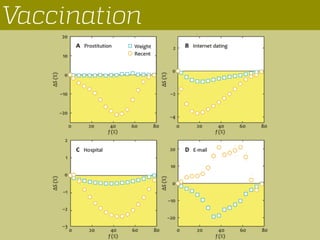

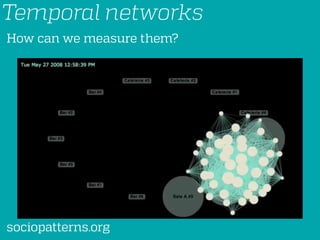

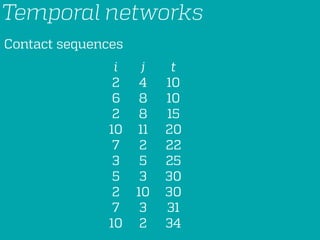

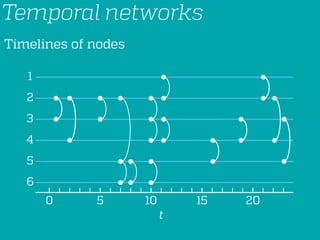

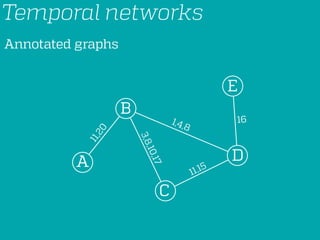

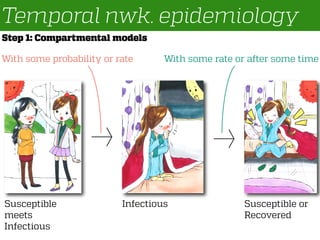

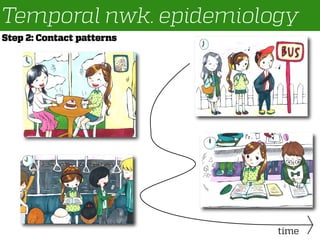

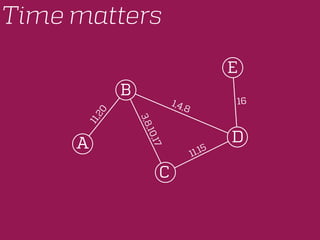

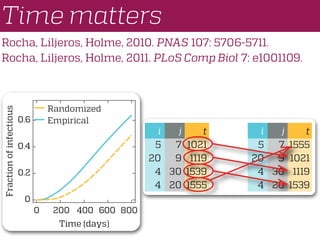

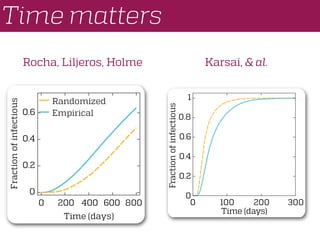

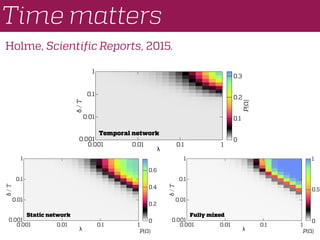

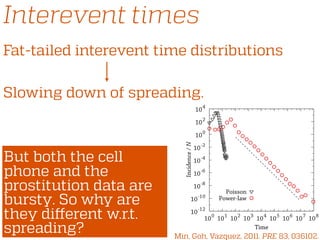

This document discusses temporal networks and how temporal structures can impact dynamical processes on networks. It begins by describing different types of temporal networks including person-to-person communication, information dissemination, physical proximity, and cellular biology networks. It then discusses methods for analyzing temporal network structures like inter-event times and how bursty or heavy-tailed distributions can slow spreading compared to memory-less processes. The document also presents examples of how neutralizing temporal structures like inter-event times or beginning/end times can impact spreading simulations. Finally, it discusses how different temporal network datasets exhibit diverse temporal structures.

![Europhys. Lett., 64 (3), pp. 427–433 (2003)

EUROPHYSICS LETTERS 1 November 2003

Network dynamics of ongoing social relationships

P. Holme(∗

)

Department of Physics, Ume˚a University - 901 87 Ume˚a, Sweden

(received 21 July 2003; accepted in final form 22 August 2003)

PACS. 89.65.-s – Social and economic systems.

PACS. 89.75.Hc – Networks and genealogical trees.

PACS. 89.75.-k – Complex systems.

Abstract. – Many recent large-scale studies of interaction networks have focused on networks

of accumulated contacts. In this letter we explore social networks of ongoing relationships with

an emphasis on dynamical aspects. We find a distribution of response times (times between

consecutive contacts of different direction between two actors) that has a power law shape over a

large range. We also argue that the distribution of relationship duration (the time between the

first and last contacts between actors) is exponentially decaying. Methods to reanalyze the data

to compensate for the finite sampling time are proposed. We find that the degree distribution

for networks of ongoing contacts fits better to a power law than the degree distribution of

the network of accumulated contacts do. We see that the clustering and assortative mixing

coefficients are of the same order for networks of ongoing and accumulated contacts, and that

the structural fluctuations of the former are rather large.

Introduction. – The recent development in database technology has allowed researchers

to extract very large data sets of human interaction sequences. These large data sets are

suitable to the methods and modeling techniques of statistical physics, and thus, the last years

have witnessed the appearance of an interdisciplinary field between physics and sociology [1–3].

More specifically, these studies have focused on network structure —in what ways the networks](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/tmpnwk-160428131248/85/Spreading-processes-on-temporal-networks-27-320.jpg)