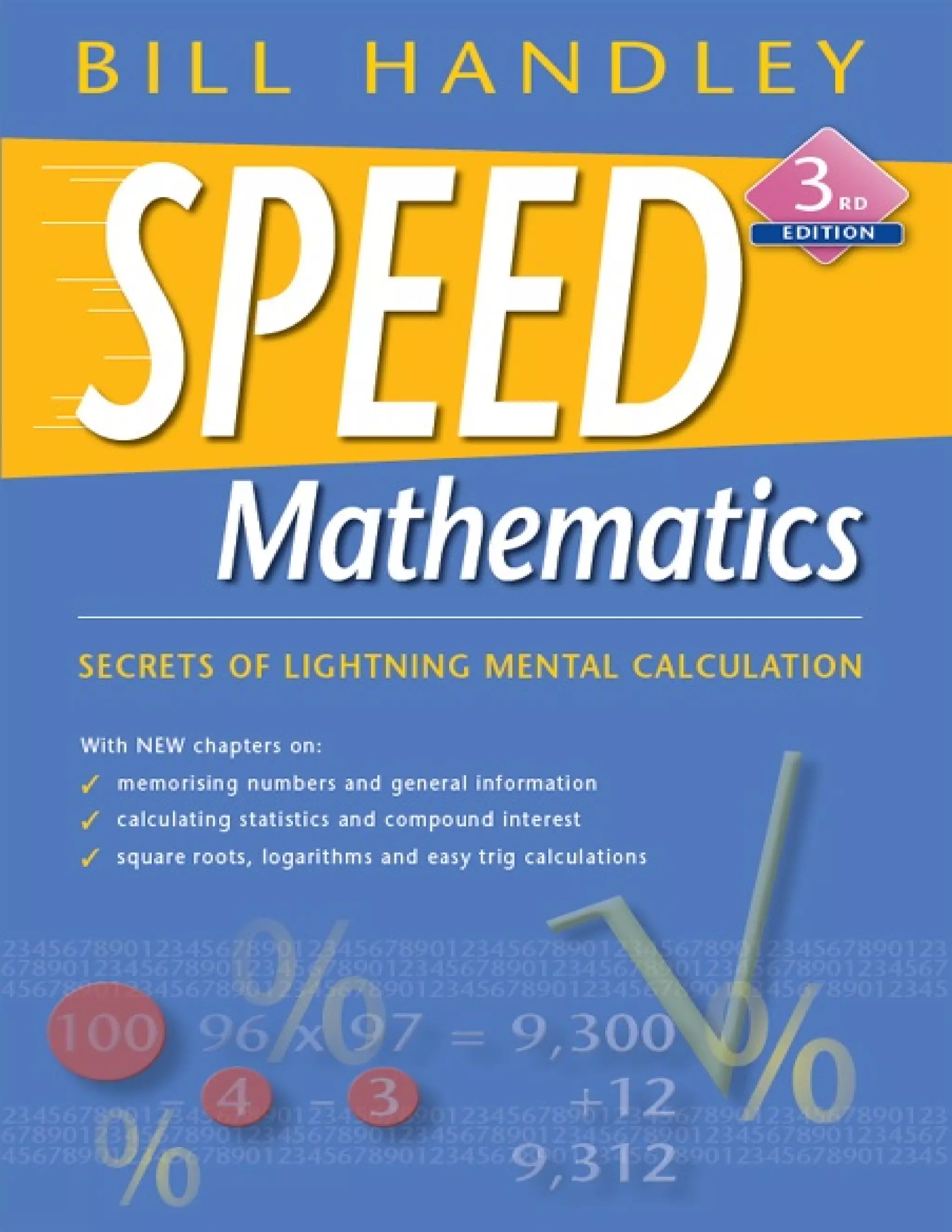

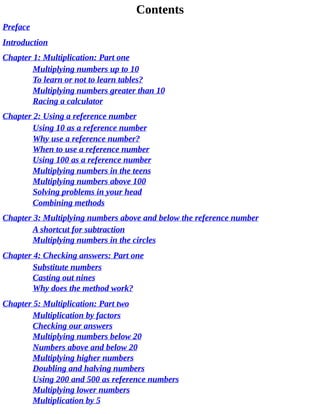

This document provides a table of contents for a book on speed mathematics. The book covers various math topics across 29 chapters, including multiplication, division, fractions, decimals, square roots, and mental calculation strategies. It also includes 8 appendices with additional information on topics like checks for divisibility and square roots of feet and inches. The goal of the book is to teach readers how to perform complex math calculations in their heads faster than using a calculator.

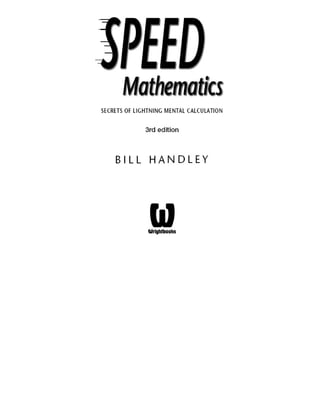

![To square 23 you square 25 (625) and subtract twice 23 + 25.

23 + 25 = 48

48 × 2 = 96 (48 = 50 − 2 2[50 − 2] = 100 − 4)

625 − 96 = 529

The numbers above 25 follow the same pattern. To square 26 you consider it as 1 above 25. Twenty-

five squared is 625, 25 + 26 is 51.

625 + 51 = 676

Consider 27 as 2 above 25. Twenty-five squared = 625.

25 + 27 = 52

Twice 52 is 104. Six hundred and twenty-five plus 104 equals 729.

Twenty-eight is 2 below 30. Thirty squared is 900.

30 + 28 = 58

58 × 2 = 116

900 − 116 = 784

All of these calculations can be made mentally.

Try these calculations for yourself:

a) 422

b) 332

c) 382

d) 772

The answers are: a) 1764 b) 1089 c) 1444 d) 5929

An easy option for problem b) would be to consider 33 as 3 above 30.

302

= 900

30 + 33 = 63

63 × 3 = 189

900 + 189 = 1089

An easier method of solving problem a) would be to use the method for numbers near 50.

50 − 42 = 8

25 − 8 = 17 (1700 becomes our subtotal)

82

= 64

1700 + 64 = 1764

You now have a choice of methods for squaring numbers.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/speedmathematicssecretsofmentalcalculation-220129163831/85/Speed-mathematics-secrets-of-mental-calculation-71-320.jpg)