Sound and Image Aesthetics and Practices Sound Design 1st Edition Andrew Knight-Hill (Editor)

Sound and Image Aesthetics and Practices Sound Design 1st Edition Andrew Knight-Hill (Editor)

Sound and Image Aesthetics and Practices Sound Design 1st Edition Andrew Knight-Hill (Editor)

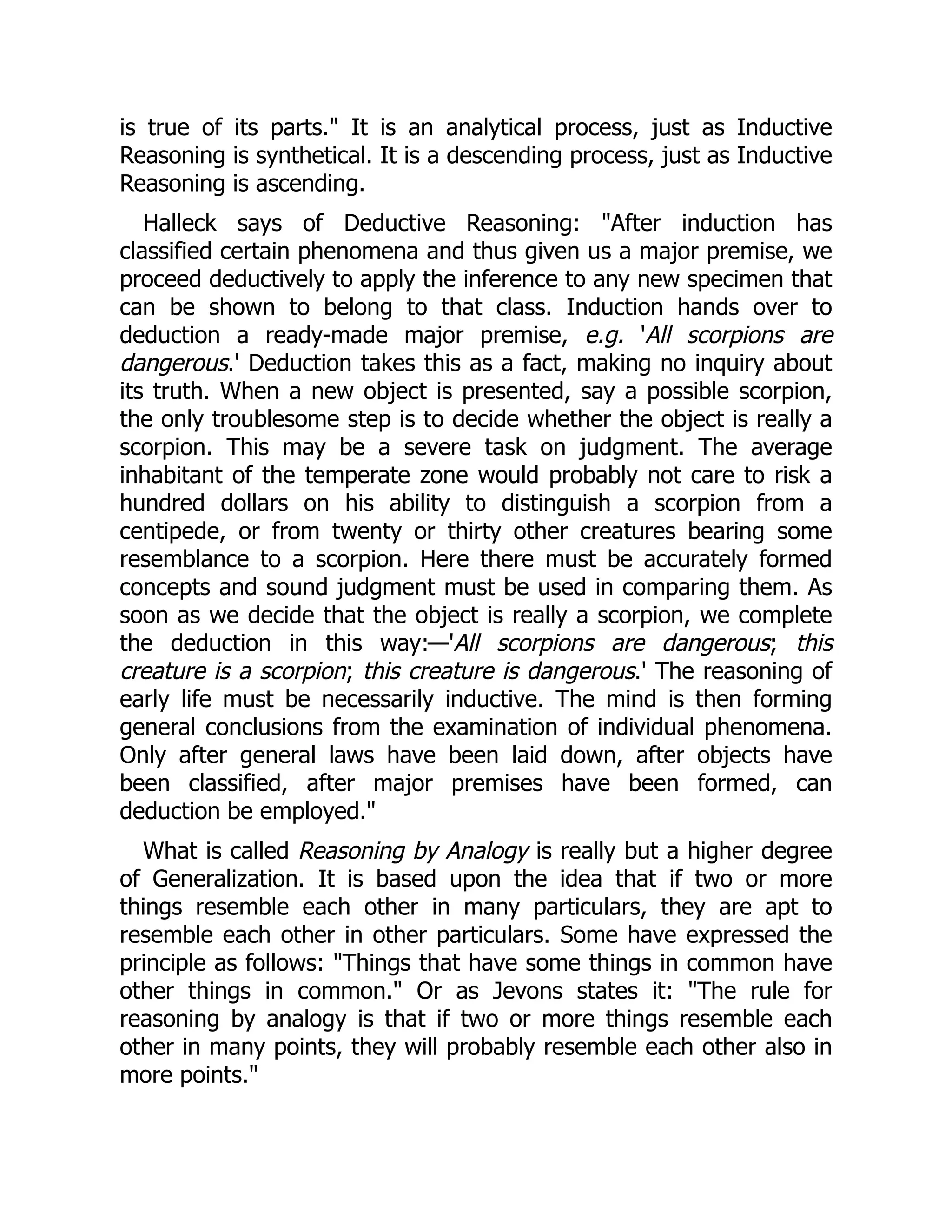

![viii Contents

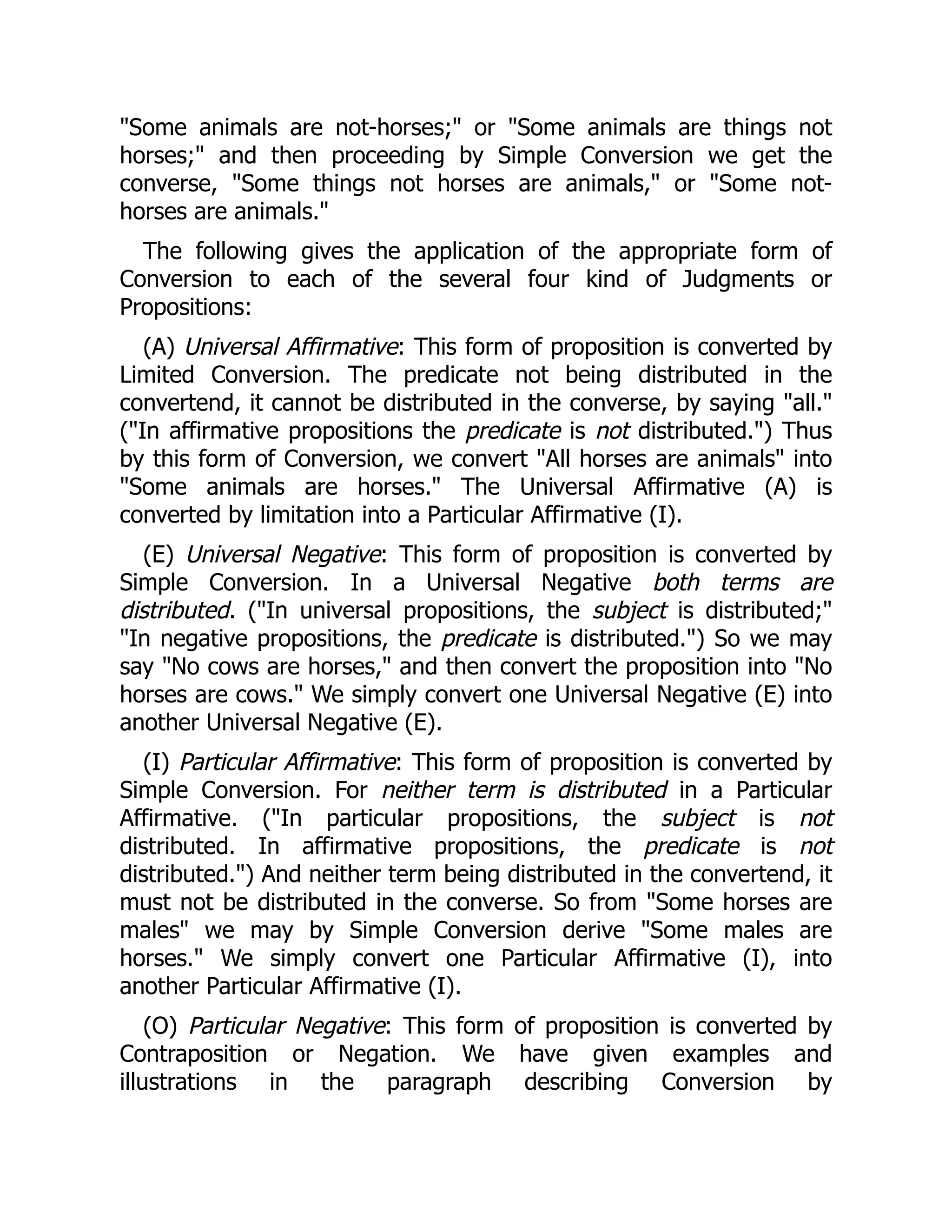

10 The function of Mickey-Mousing: a re-assessment

EMILIO AUDISSINO

145

11 Performing the real: audiovisual documentary performances and

the senses 161

CORNELIA LUND

12 Blending image and music in Jim Jarmusch’s cinema

CELINE MURILLO

177

13 The new analogue: media archaeology as creative practice in

21st-century audiovisual art

JOSEPH HYDE

188

14 Screen grammar for mobile frame media: the audiovisual language

of cinematic virtual reality, case studies and analysis

SAM GILLIES

206

15 Nature Morte: examining the sonic and visual potential of a

16mm flm 219

JIM HOBBS

16 Capturing movement: a videomusical approach sourced in the

natural environment 226

MYRIAM BOUCHER

17 Constructing visual music images with electroacoustic music

concepts

MAURA MCDONNELL

240

18 Technique and audiovisual counterpoint in the Estuaries series

BRET BATTEY

263

19 Exploring Expanded Audiovisual Formats (EAFs) – a practitioner’s

perspective

LOUISE HARRIS

281

20 Making a motion score: a graphical and genealogical inquiry into

a multi-screen cinegraphy

LEYOKKI

294

21 The human body as an audiovisual instrument

CLAUDIA ROBLES-ANGEL

316

22 Sound – [object] – dance: a holistic approach to interdisciplinary

composition

JUNG IN JUNG

331](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/65095-250502041636-f8eda57d/75/Sound-and-Image-Aesthetics-and-Practices-Sound-Design-1st-Edition-Andrew-Knight-Hill-Editor-12-2048.jpg)

![6 Diego Garro

Mapping between sound and images

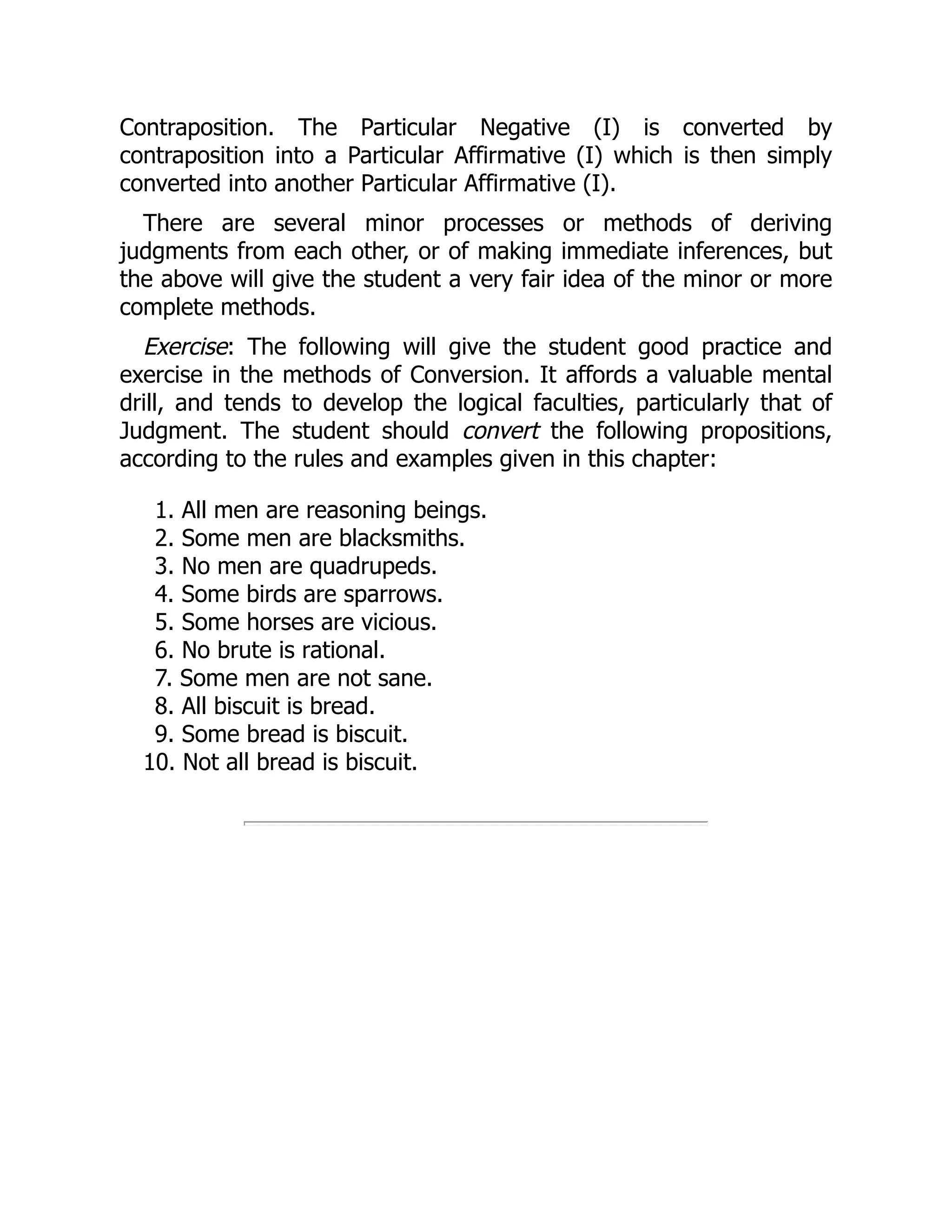

Strategies to combine sound and images have been the subject of study and experi-

mentation for centuries, from Isaac Newton and his correspondences colour-pitch,

through the inventors of the colour organs down to the creators of modern music

visualiser software such as those supported by iTunes, Windows Media Player

and WinAmp (Collopy 2000). Furthermore, psychologists of cognition have been

intrigued since the beginning of the 20th century by so-called synaesthesic corre-

spondences correspondences, within which stimuli in one sense modality is trans-

posed, to a different modality (for example, in some individuals certain sounds are

perceived with an strong sense of certain taste/favours).

Many strategies of mapping audio and visual have concentrated on seeking

to establish normative mappings between sound pitches and colour hues, in an

attempt to create a ‘colour harmony/disharmony’ that can be related to musical

consonance/dissonance. Fred Collopy provides a compendium of possible ‘cor-

respondences’ between music and images (see for example a summary of the vari-

ous ‘colour scales’ developed by thinkers and practitioners over three centuries to

associate normatively certain pitches in the tempered scale with certain colour hues

[Collopy 2001]).

However, prescriptive mapping techniques, such as colour-scales, quickly become

grossly inadequate once the palette of sound and visual material at a composers’

disposal expands. If models for correspondences are to be sought, they need to

account for more complex phenomenoloies of audio and video stimuli, far beyond

simplistic mappings between, for example, musical pitch and colour hue, or sound

loudness and image brightness.

Let us, for a start, introduce a taxonomy of phenomenological parameters of

the moving image and of sound, that we may consider a deeper mapping strategy

between the two media.2

Phenomenological parameters of the moving image

● Colour – hue, saturation, value (brightness).

● Shapes – geometry, size.

● Surface texture.

● Granularity – single objects, groups/aggregates, clusters, clouds.

● Position/Movement – trajectory, speed, acceleration in the (virtual) 2-D or 3-D

space recreated on the projection screen.

● Surrogacy – links to reality, how ‘recognisable’ and how representational visual

objects are.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/65095-250502041636-f8eda57d/75/Sound-and-Image-Aesthetics-and-Practices-Sound-Design-1st-Edition-Andrew-Knight-Hill-Editor-28-2048.jpg)

![8 Diego Garro

which depend more directly on multi-dimensional interplay of tension and

resolution.

(extrapolated from John Whitney’s idea of ‘complementarity’

between music and visual arts [Alves 2005: 46])

From ‘mapping’ to ‘composing’

The “multi-dimensional interplay of tension and resolution” mentioned by Alves

indicates an angle of analysis creativity that is richer than parametric mapping,

albeit less rigorous, because the articulation of tension-release is indeed a more use-

ful compositional paradigm than any, more or less formalised, mapping between

audio and video material.

Instead of pursuing strict parametric mapping of audio into video or vice versa,

composers can aim at the formulation of a more complex ‘language’ based on the

articulation of sensory and emotional responses to artistically devised stimuli.

Roger B. Dannemberg observed that composers may opt for connections between

sound and moving image that, because they are based on explicit mapping, operate

at very superfcial levels. He advocates links between the two dimensions that are

not obvious, but are somewhat hidden within the texture of the work, at a deeper

level. Audiences may grasp intuitively the existence of a link and feel an emotional

connection with the work, while the subtlety of this link allows the viewer to relate

to the soundtrack and the video track as separate entities, as well to the resulting

‘Gestalt’ of the combination, thus fnding the work more interesting and worth

repeated visits (Dannemberg 2005: 26).

A beautiful example of such approach can be found in Dennis H. Miller’s work

Residue (1999) (Figure 1.1). At the onset of this audiovisual composition a mov-

ing, semi-transparent cubic solid, textured with shifting red vapours, is associated

with long, ringing inharmonic tones on top of which sharp reverberated sounds –

resembling magnifed echoes of water drops in a vast cavern – occasionally appear.

The association between the cube and the related sounds cannot be described in

parametrical mapping terms and, in fact, seems at frst rather arbitrary. However,

the viewer is quickly transported into an audiovisual discourse that is surprisingly

coherent and aesthetically enchanting. It is clear that those images and sounds

‘work well’ together although we are not able to explain why, certainly not in terms

of parametric mapping. A closer analysis of this work, and others by the same

author, reveals that it is the articulation in time of the initial, deliberate, audiovi-

sual association that makes the associations so convincing: we do not know why

the red cube is paired with inharmonic drones at the very onset of Residue but,

once that audiovisual statement is made, it is then articulated in such a compel-

ling way – by means of alternating repetitions, variations, developments – that the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/65095-250502041636-f8eda57d/75/Sound-and-Image-Aesthetics-and-Practices-Sound-Design-1st-Edition-Andrew-Knight-Hill-Editor-30-2048.jpg)