The document provides a comprehensive overview of Solidity and smart contract development, focusing on key topics like the Ethereum Virtual Machine, account types, memory management, data types, and function behavior. It discusses error handling techniques, gas optimization strategies, and the trade-offs between deployment and execution costs in Solidity programming. Additionally, it includes examples and best practices for optimizing gas usage in smart contracts.

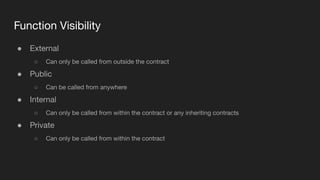

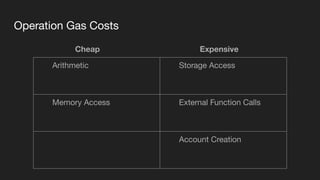

![Unpackable Packed

uint128 a;

uint256 b;

uint128 c;

uint128 a;

uint128 c;

uint256 b;

a b c

Slot 0 Slot 1 Slot 2

a b [empty]

Slot 0 Slot 1 Slot 2

c](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/soliditygasoptimization-220927022950-dbb5b94b/85/Solidity-and-Ethereum-Smart-Contract-Gas-Optimization-21-320.jpg)

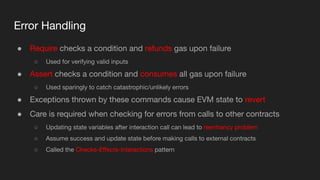

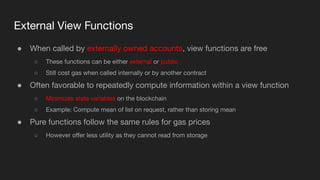

![Code Example

● Sample contract with 5 levels of

optimization

● Each implementation computes

sum of a dynamic array

● Gas costs applicable when called

by another contract

● Detailed comments at:

github.com/zlafeer/solidity-optimization

// Constructs dynamic array

// of n unsigned integers

uint[] private storageArray;

constructor(uint n) {

for (uint i = 0; i < n; i++) {

storageArray .push(i%10);

}

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/soliditygasoptimization-220927022950-dbb5b94b/85/Solidity-and-Ethereum-Smart-Contract-Gas-Optimization-26-320.jpg)

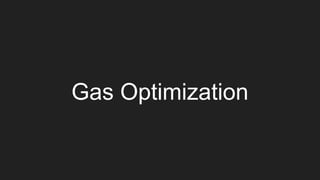

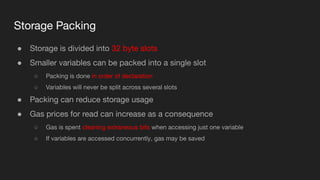

![// Naive

// 100% Gas Cost

function sumA() public view returns (uint) {

uint sum = 0;

for (uint i = 0; i < storageArray.length; i++) {

sum += storageArray[i];

}

return sum;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/soliditygasoptimization-220927022950-dbb5b94b/85/Solidity-and-Ethereum-Smart-Contract-Gas-Optimization-27-320.jpg)

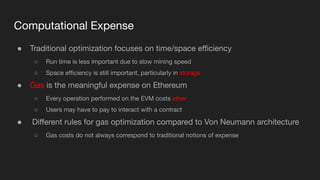

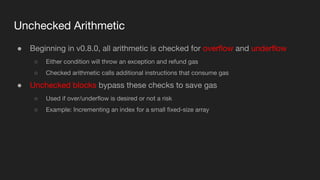

![// Memory Caching

// ~93% Gas Cost

function sumB() public view returns (uint) {

uint[] memory memoryArray = storageArray;

uint sum = 0;

for (uint i = 0; i < memoryArray.length; i++) {

sum += memoryArray[i];

}

return sum;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/soliditygasoptimization-220927022950-dbb5b94b/85/Solidity-and-Ethereum-Smart-Contract-Gas-Optimization-28-320.jpg)

![// Unchecked Arithmetic

// ~91% Gas Cost

function sumC() public view returns (uint) {

uint[] memory memoryArray =

storageArray;

uint sum = 0;

uint i = 0;

while (i < memoryArray.length) {

sum += memoryArray[i];

unchecked {

i++;

}

}

return sum;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/soliditygasoptimization-220927022950-dbb5b94b/85/Solidity-and-Ethereum-Smart-Contract-Gas-Optimization-29-320.jpg)

![// Inline Assembly

// ~87% Gas Cost

function sumD() public view returns (uint) {

uint[] memory memoryArray = storageArray;

uint sum = 0;

uint i = 0;

while (i < memoryArray.length) {

assembly {

sum := add (sum, mload(add(add(memoryArray, 0x20), mul(i, 0x20))))

i := add (i, 0x01)

}

}

return sum;

}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/soliditygasoptimization-220927022950-dbb5b94b/85/Solidity-and-Ethereum-Smart-Contract-Gas-Optimization-30-320.jpg)