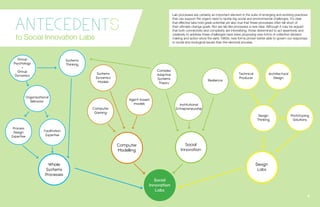

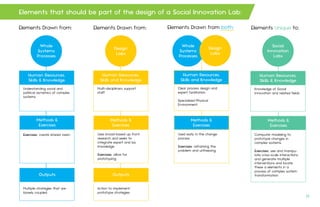

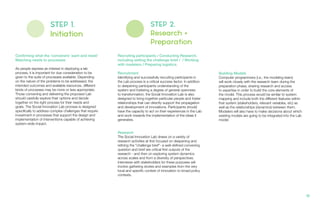

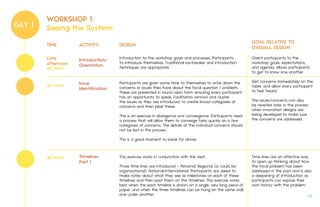

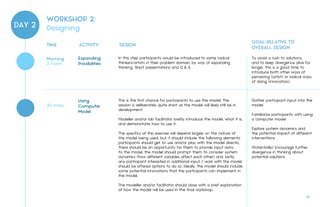

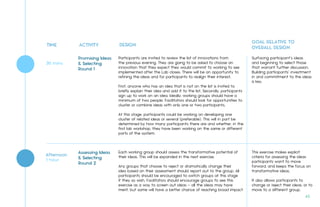

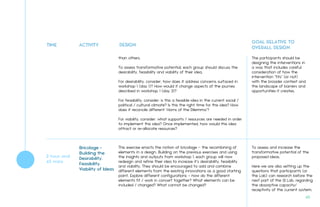

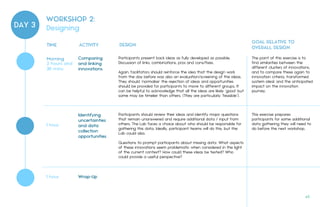

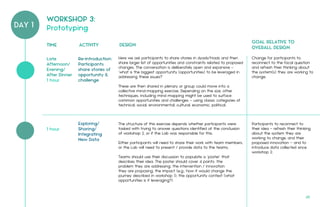

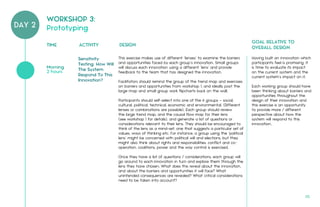

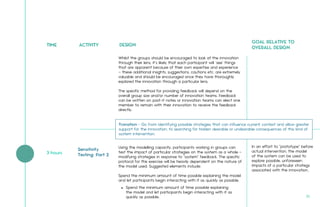

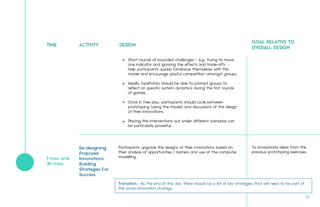

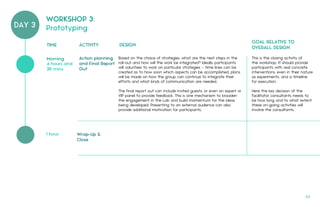

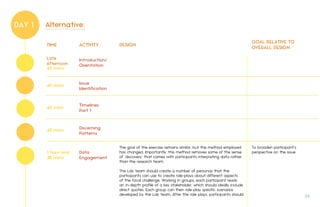

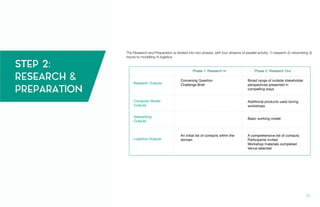

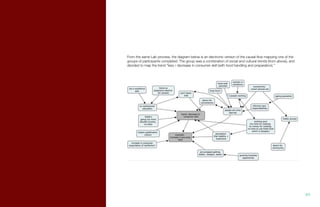

The document provides a guide to establishing a social innovation lab, detailing a three-step process that includes initiation, research, and workshops to tackle complex social problems. This methodology emphasizes collaboration among multi-stakeholder groups and utilizes computer modeling to prototype interventions. The guide aims to empower practitioners, leaders, and citizens to transform social challenges into actionable solutions, fostering a greater sense of agency in driving systemic change.