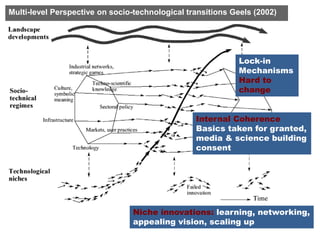

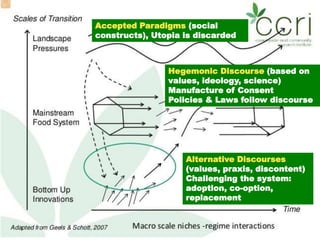

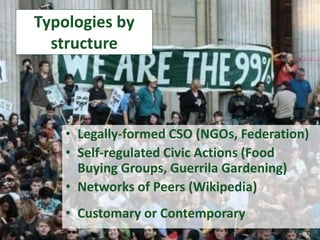

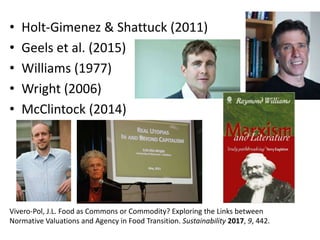

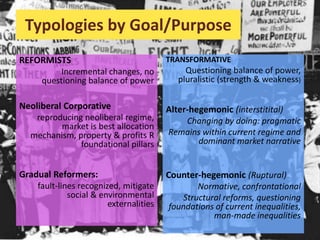

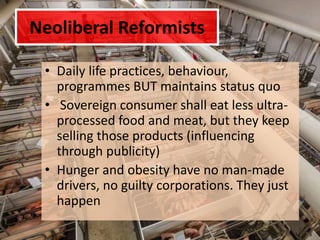

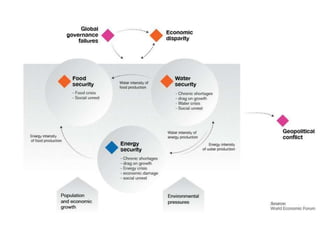

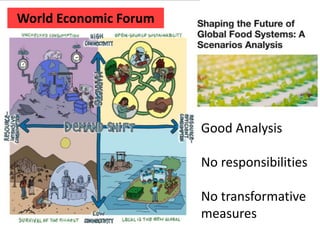

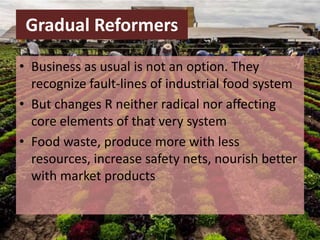

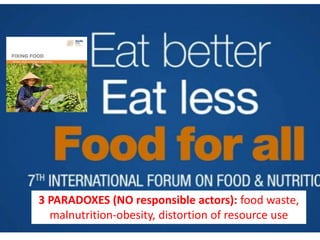

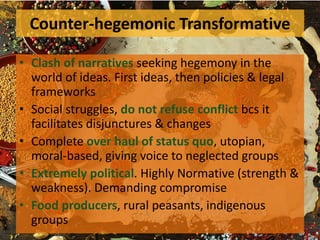

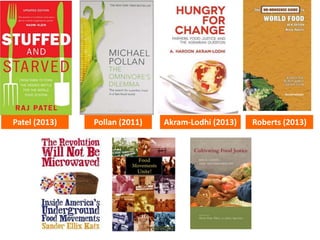

This document discusses theoretical approaches for understanding social food movements. It defines social food movements as civic collective actions focused on food and analyzes their different constituencies. It also presents typologies for categorizing these movements based on their structure, goals, and degree of transformation sought. Reformist movements seek incremental change within the existing system, while transformative movements more fundamentally question existing power balances and can be alter-hegemonic or counter-hegemonic in nature. The document draws on literature discussing these approaches and debates regarding social movements' potential to reform or transform current food systems.