The authors introduce a systematic review of articles in the area of software engineering security challenges on the cloud. The review examines articles that were published between 2014 and 2019. The procedure for article qualification relied on the elucidation of Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses premises. Meta-analysis checklist was employed to explore the analytical quality of the reviewed papers.

This paper presents the results of an SLR on research approaches and tools for the deployment and orchestration of IoT systems. From thousands of relevant publications, 17 primary studies were systematically identified and reviewed for data extraction and synthesis to answer the predefined research questions.

Focusing on an urban-scale, this study systematically reviews 70 journal articles, published

![Gough, David A., David Gough, Sandy Oliver, and James Thomas. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. Systematic Reviews. London: SAGE, 2012.

Grant, M. J. & Booth, A. (2009) A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal 26(2), 91-108

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing

between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Pittway, L. (2008) Systematic literature reviews. In Thorpe, R. & Holt, R. The SAGE dictionary of qualitative management research. SAGE Publications Ltd

doi:10.4135/9780857020109

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D & Smart, P. (2003) Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal

of Management 14(3), 207-222

According to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, a systematic review attempts to gather all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified criteria in order to

answer a specific research question. A systematic review has: 1) a clearly stated set of objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies; 2) an explicit, reproducible

methodology; 3) a thorough, objective and reproducible search of a range of sources to identify as many relevant studies as possible; 4) an assessment of the validity of the

findings for the included studies; 5) a systematic presentation and synthesis of the characteristics and findings of the studies.

Source: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, 2019. Available from

www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

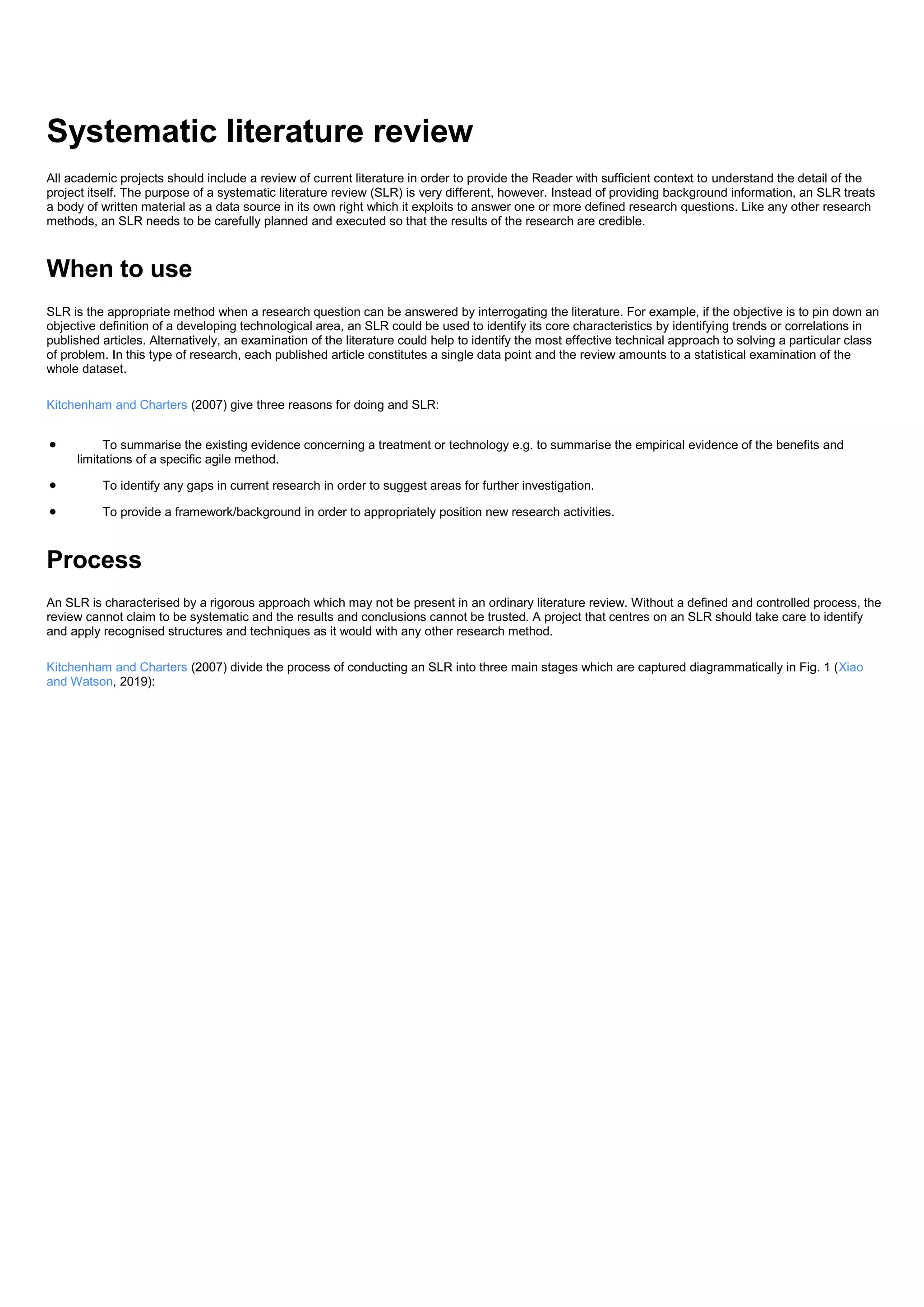

The Systematic Review Process

1. Define your research question.

2. Determine that there are no existing systematic reviews or systematic review protocols that address your question.

3. Assemble your research team. The team should ideally include subject area specialists, a specialist versed in systematic review methods and a

librarian/information specialist who has had training in systematic review methods.

4. Develop your protocol, which is a detailed description of the objectives and methods of the review. It should include the rationale and objectives of the review, the

inclusion/exclusion of the criteria, methods for locating studies, quality assessment methods, data extraction methods, data synthesis methods,etc.

5. Register your protocol.

6. Review the literature to search for studies.

7. Screen titles and abstracts to identify potentially relevant studies.

8. Review full-text and apply inclusion and exclusion criteria.

9. Assess quality of eligible studies.

10. Depending on the type of review, extract data from individual studies.

11. Analyze data and synthesize if appropriate.

12. Report findings.

Articles

EPPI-Centre (2019). What is a systematic review? UCL Institute of Education, University College London.

Henderson, Lorna K (09/2010). How to write a Cochrane systematic review. Nephrology (Carlton, Vic.) (1320-5358), 15(6), p. 617.

National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools. (2014). Anatomy of a Systematic Review [fact sheet].

Riesenberg, Lee Ann (04/2014). Conducting a successful systematic review of the literature, part 1. Nursing (Jenkintown, Pa.) (0360-4039), 44 (4), p. 13.

Riesenberg, Lee Ann (06/2014). Conducting a successful systematic review of the literature, part 2. Nursing (Jenkintown, Pa.) (0360-4039), 44 (6), p. 23.

Umscheid, Craig A (09/2013). A Primer on Performing Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Clinical infectious diseases (1058-4838), 57 (5), p. 725.

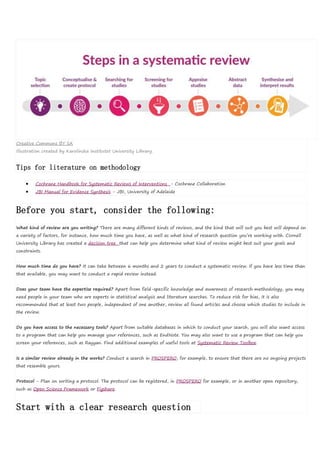

Steps in the Literature Review Process

1. Define the research question (for more)

1. You may need to some exploratory searching of the literature to get a sense of scope, to determine whether you need to narrow or broaden your focus

2. Identify databases that provide the most relevant sources, and identify relevant terms (controlled vocabularies) to add to your search strategy

3. Finalize your research question](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/slr-230822171946-ee6526e7/85/SLR-docx-17-320.jpg)