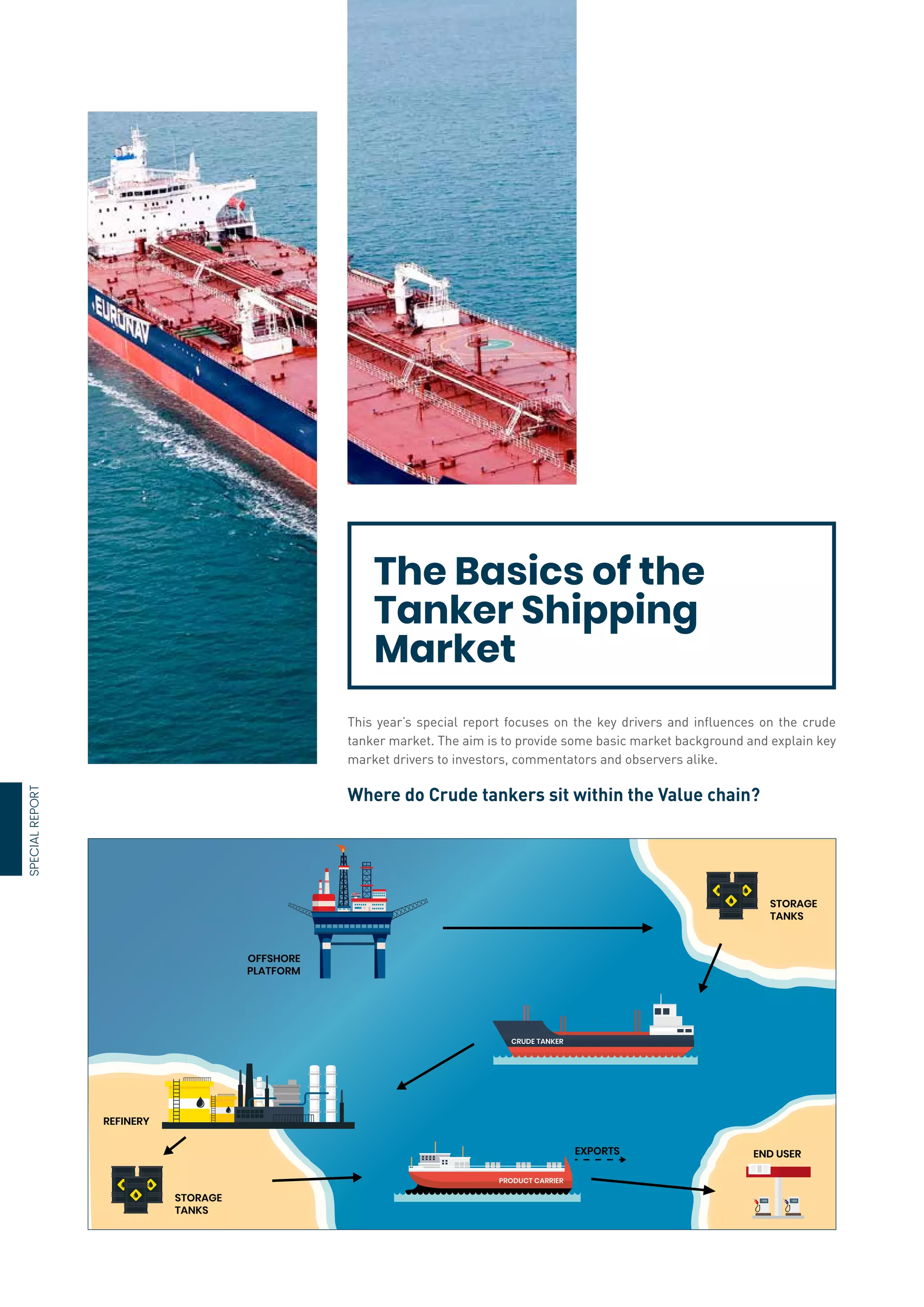

- Crude oil tankers transport crude oil from production points to refineries and come in various sizes from Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs) to smaller Aframax tankers.

- Freight rates are determined through negotiations between ship brokers and owners with the number of eligible vessels impacting prices.

- Tanker shipping is influenced by oil prices, with lower prices generally boosting demand for oil transportation but very low prices potentially reducing production.