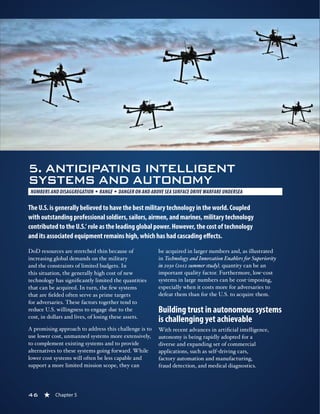

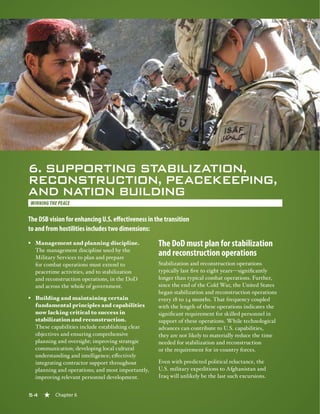

This document summarizes the key findings and recommendations from reports published by the Defense Science Board over the past dozen years. It identifies seven major themes that dominated the Board's work: 1) protecting the homeland, 2) deterring nuclear weapons, 3) preparing for "gray zone" conflicts, 4) maintaining information superiority, 5) anticipating intelligent systems and autonomy, 6) supporting stabilization and nation-building, and 7) preparing for surprise. The document provides an overview of each theme and references underlying reports to aid the incoming administration in addressing pressing national security issues.