The politicization myth holds that greater political control over policing would undermine operational independence. However, politicians already interfere in policing practices through numerous targets and initiatives, preventing chief constables from directing strategy. Senior police officers also spend time influencing politics. While operational decisions remain with police leaders, the current tripartite system lacks clear accountability. Politicians set policing priorities but cannot control strategy, while police chiefs manage operations but not strategic direction. This confusion of roles prevents effective accountability and reform.

![A new force

The myths of policing

priorities.17 Decisions on policing strategy go through ACPO committees.

One high-profile example of political involvement was the former Metropolitan Police Commissioner, Sir

Ian Blair, who campaigned publicly in favour of the Government’s plans to introduce identity cards and to

allow detention without charge for 42 days. The result of this was an erosion of trust and the widespread

questioning of Sir Ian’s independence.18

A force of “robots”

The result of the centralisation of policing practice is police officers who do not use discretion. This has been

amplified by the centralisation of operational decisions and technological changes – people now interact with the

police by phone, not in person. Force Control Rooms determine the location and response of police on the beat,

directing them to the crime scenes which are deemed the most important. But this strategy has transferred

management of uniformed patrol officers from police Basic Command Units (BCUs) to civilian control room

operators.The result is that BCU Commanders have no real control over the deployment of their patrol staff.19

This has led to the creation of a dependency culture amongst patrol officers who now just go where they are

told. The prestige and power of junior managers such as Sergeants has been reduced to that of a highly-paid

Constable.20 The proliferation of “civilians” in these areas has further implications. Reform has been told

that after the Metropolitan Police centralised operations into three control rooms, staff have refused to stay

once their hours are up, even if there is an large-scale emergency in progress.

Tripartite risk sharing

Accountability is diluted by the tripartite structure of police governance, which shares risk and blame across

three parties: the Home Office, Police Authorities and Chief Constables. ACPO’s role in it is akin to the

British Medical Association being part responsible for the running of the health service or the Association

of Head Teachers approving education plans. ACPO’s blurred purpose and responsibility does not help.

Shami Chakrabarti, Director of Liberty, recently said:

“[ACPO] advises government, it sets policing policy, it campaigns for increased police powers, and

now we learn it is engaged in commercial activities – all with a rather shady lack of accountability.”21

ACPO’s incorporation as a private company shields it from accountability, for example through the

Freedom of Information Act.22

Accountability and the Metropolitan Police

The Metropolitan Police is unique in that, as well as being London’s “local” police force, it has national

responsibilities, in particular for counter-terrorism.23 This dual role results in confused accountability. The

Metropolitan Police Commissioner reports both to the Home Secretary, for national serious crime, and the

Mayor of London, for local policing. As such he is not accountable to any single person or body.

A lack of local accountability

The Home Office has filled the vacuum of accountability by taking more responsibility for decision-making

along with ACPO. In other public services, such as health and education, government departments have

also asserted their control. But these decisions have been balanced (admittedly to a very limited extent) by

efforts to increase the power of local decision-makers, for example through greater choice of hospital for

patients or choice of new types of school.

Policing has not seen a comparable increase in local accountability. Part of the issue is the wider problem of

weak local government structures in England and Wales. Because local government relies on central

7 iller, J. (200), Police Corruption in England and Wales: An assessment of current evidence, Home Office; The Independent (2005),

M

“Police accused of lobbying MPs over shooting”, 6 November: The aftermath of the shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes has shown

some members of the police attempting to involve themselves with government policy and investigations.

8 aville, S. (2008), “The fall and fall of Sir Ian Blair”, The Guardian, 2 October: “Early in his tenure Blair earned the reputation for being a New

L

Labour lackey. Lobbying first for identity cards and later for detention for 2 days without trial, he was accused of being a mouthpiece for

his namesake, the then prime minister, Tony Blair.”

9 N

orthamptonshire Police (2009), Force Communications Centre recruitment website (http://www.greatunderpressure.co.uk/fcro.html):

“Force Control Room Operatives direct and control police incidents ensuring the timely deployment of appropriate resources to ensure

successful resolution.”

20 rooks, P. (2002), “Putting civvies in the control room is asking for trouble”, The Guardian, 5 October: “If you put a civilian in a job where

B

someone has to think like a police officer – the control room, for instance – then you ask for trouble. Imagine the army sending civilians

out to battlefields to control a war, it doesn’t make sense. Well it’s the same in the police service.”

2 ones, S. (2009), “Police chiefs body faces calls for review after cash revelations”, The Guardian, 6 February.

J

22 ssociation of Chief Police Officers (2007), ACPO and the Freedom of Information Act 2000: “ACPO is a private company and the Office

A

of the Information Commissioner has confirmed that the Freedom of Information Act does not apply to the Association, since Schedule

of the Act does not include a definition which covers ACPO.”

2 etropolitan Police Authority (2008), Policing London Annual Report 07/08.

M

0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/salesstrategydocumentation-12561338655456-phpapp01/75/Sales-Strategy-Documentation-11-2048.jpg)

![A new force

The myths of policing

government for the great majority of its income, its own accountability is blurred and uncertain.24 Equally,

the territories of most police forces are not coterminous with local government boundaries, making it

impossible for citizens to know who is responsible for policing in their area.25

Proposals to increase local accountability have an unhappy history.The most recent example that foundered was

Jacqui Smith’s plans to elect Police Authority members.26 One reason for successive Home Secretaries’ lack of

success may be their failure to address the structural problems of local accountability, in particular the uncertain

relationship between police and councils. The result of this is, in the words of one commentator, “a huge gap

between how we want to be policed, how the police want to police us and how we are actually policed.”27

The Bichard Inquiry into the murders of Holly Wells and Jessica Chapman in Soham, Cambridgeshire

strongly criticised the “worrying” lack of “clarity of accountability” of the police.28

The secret police

There is a distinct lack of transparency of information available about the police. Reform has repeatedly

found that attempts to research specifics on police budgets, strategies and accountability structures have

been futile. Although Police Authorities do publish high-level annual budgets, there are no detailed,

publicly-accessible accounts. There is no clear document explaining who reports into whom, particularly in

terms of national bodies. Enquiries directly to police forces have yielded some information, but in many

cases they have refused to help or suggested a Freedom of Information request.

The Policing and Crime Bill

The Policing and Crime Bill currently going through Parliament significantly tones down the pledges in the

policing Green Paper on local accountability. Instead of endorsing the direct election of some members of

Police Authorities the Bill calls for Police Authorities to “have regard to the views of the public”.29 Vernon

Coaker, the Police Minister, has argued that this will “strengthen [Police Authorities’] current duty”, but

David Ruffley, his Shadow, concluded that it represents “a very modest change”.30

The Bill also creates a Police Senior Appointments Panel to advise the Home Secretary on the appointment

of senior police officers.31 This would be a change from the current system where senior police officer roles

are advertised by Police Authorities. The successful candidate is appointed by the relevant Police Authority,

subject to approval by the Home Secretary.

The new Panel will consist of members nominated by the Home Secretary, the Association of Police

Authorities (APA) and ACPO. This will therefore reduce accountability since Police Authorities will have

less of a say in order to make room for ACPO, who will in effect become responsible for appointing their

own people. The proposed appointment structure will strengthen the “self-perpetuating oligarchy” that is

ACPO by embedding it at all levels. Chris Grayling, the Shadow Home Secretary, commented:

“It is strange that [the Bill] gives ACPO a statutory position in advising on appointments when the

status of ACPO itself remains undefined. Is it an external reference group for Home Office Ministers,

or a professional association protecting senior officers’ interests? Is it a national policing agency, or is

it a pressure group arguing for greater police powers?”32

Conclusion

The problem for the police is not politicisation; it is a lack of accountability.

The tripartite model and in particular the role of ACPO creates an accountability gap.

Greater local political control over most police priorities would enhance accountability. It would

clarify who is responsible for police performance (the police) and who can be changed in order to

change those priorities (locally elected representatives).

Better accountability will sharpen management within police forces.

2 D

epartment for Communities and Local Government (2008), http://www.communities.gov.uk/localgovernment/

localgovernmentfinance/counciltaxes/counciltaxfacts/: Central government is providing local councils in England with over £70 billion in

2008/2009. Total local government revenue expenditure in 2008-09 is £98. billion.

25 eform research: Only of the forces are coterminous with the boundaries of local government structures (see Appendix).

R

26 he Guardian (2008), “Labour forced to ditch police elections plan”, 8 December.

T

27 ergeant, H. (2008), “The dangerous gap in policing”, The Sunday Times, 25 May.

S

28 ichard, M. (200), The Bichard Inquiry Report.

B

29 P

olicing and Crime Bill 2008-09.

0 H

ouse of Commons Public Bill Committee (2009), th Sitting, 29 January.

P

olicing and Crime Bill 2008-09.

2 H

ansard (2009), 9 January, Col. 258.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/salesstrategydocumentation-12561338655456-phpapp01/75/Sales-Strategy-Documentation-12-2048.jpg)

![A new force

The myths of policing

Myth : The local force myth

“The civilisation of many English counties is sufficiently backward to make it hazardous for the

Crown to part with power over the police; even if that power should be looked on as a proper

municipal attribute, which I am inclined to doubt.”

Lord Salisbury

There is a belief that the 43 forces in England and Wales are independent. Chief Constables direct their

forces, allocating funding and resources to respond to local needs and priorities. The forces are perceived to

be strong enough and of sufficient scale to cope with the demands placed upon them.

Reality: National policing is entrenched

Lord Salisbury’s remark about local policing appears to have informed the attitude of the Home Office and

ACPO. Reform has found that the UK has one of the most centralised criminal justice systems in the world.

The centralisation phenomenon has been particularly pronounced in policing, where there has been a

relentless drive towards government control through a many-layered management regime and the creation

of a multitude of new national agencies such as the Police Standards Unit and the National Policing

Improvement Agency (NPIA).33

In reality police forces are not independent. The Home Office sets strategies and targets. ACPO directs

national policy and commissions national services. The Metropolitan Police acts as the de facto national lead

police force and its Commissioner, Sir Paul Stephenson, as the country’s lead police officer and adviser to

the Home Secretary. The NPIA is also achieving some national coordination, albeit with little leverage.

The four elements of national policing

Effectively England and Wales already has national policing. The Metropolitan Police, the Home Office,

ACPO and the NPIA together provide many of the functions that national police forces cover in other

countries, albeit in a disjointed, inefficient and fragmented way.

ACPO – the power behind the throne

The Association of Chief Police Officers is a powerful and independent body consisting of Chief Constables,

Deputy Chief Constables and Assistant Chief Constables. It has a major role as the primary coordinator of

policing policy, encouraging the 43 forces in England and Wales to adopt the policies it promotes:

“Few understand that ACPO is a private company, which happens to be funded by a Home Office

grant and money from 44 police authorities. [It has an] important role in drafting and implementing

policies that affect the fundamental freedoms of this country [and has been responsible for promoting

policies including] police officers ... being equipped with 10,000 stun guns [and] the automatic number

plate recognition camera network [being] set up to record and store data from most road journeys.”34

ACPO has the ear of the Home Secretary and this, in combination with its influence over senior officers

(and those wishing to become senior officers), means it is a prominent voice in determining policy. Reform’s

interviews revealed a widespread belief that ACPO is the main party persuading forces to adopt particular

policies. If the Home Secretary wants to ensure the adoption of a policy idea, she will “strike a bargain”

with ACPO to ensure its implementation:

“ACPO is the driving force behind policy, and the Home Office succumbs, either because of its

own autocratic instincts or because the police are exceptionally good at pushing through the things

they want.”35

This focus of ACPO on national policy means that individual Chief Constables are left focusing on

administrative matters and equipment choices. In fact this situation should be reversed: ACPO could

take a useful national lead on administration and interoperability while Chief Constables focus on their

forces’ operations.

iangrande, R. et al. (2008), The lawful society, Reform.

G

orter, H. (2009), “The secret police are watching you”, Comment is free, 0 February.

P

5 I

bid.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/salesstrategydocumentation-12561338655456-phpapp01/75/Sales-Strategy-Documentation-13-2048.jpg)

![A new force

The myths of policing

The Home Office – a Faustian pact with ACPO

Given the roadblock that ACPO and the 43 forces have presented, the Government has sought to centralise

and mandate, subject to ACPO’s agreement. The 1964 Police Act enabled central government to take many

powers from local government in the name of fighting corruption.39 The 1996 Police Act enabled the Home

Secretary to set national policing priorities, leaving power resting almost exclusively between the Home

Secretary and Chief Constables.40

Since 2001 the Home Office has conducted a sustained campaign to take control of policing decisions. The

Home Office published three National Policing Plans along with a variety of supporting documents, and

established new agencies.41 Through these, the Home Office took responsibility for setting the priorities for

police forces, for setting many of their performance targets, and for key questions of operational

management. The result of this process was a considerable uniformity of activity across England and Wales,

directly in line with the Home Office’s intentions.

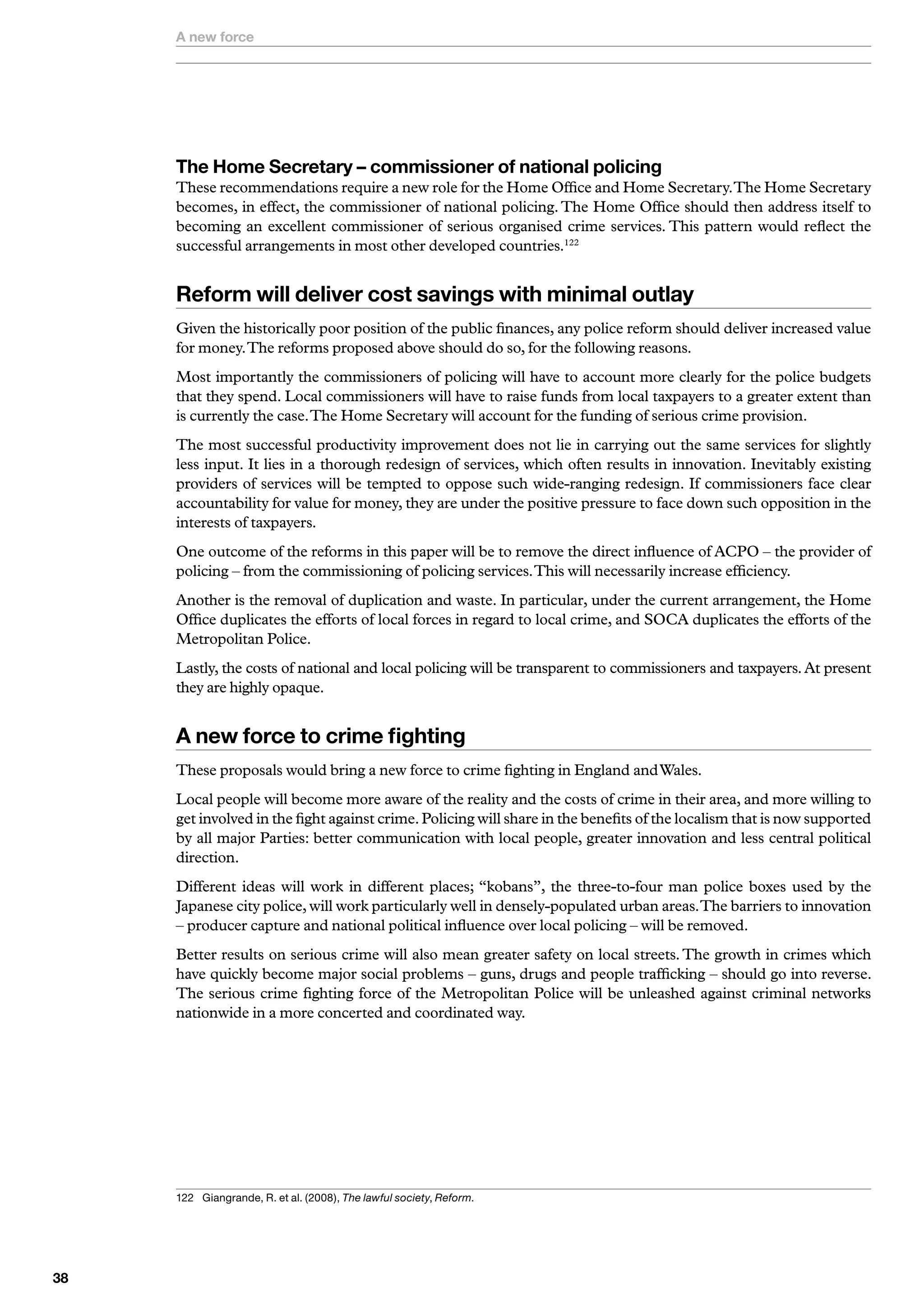

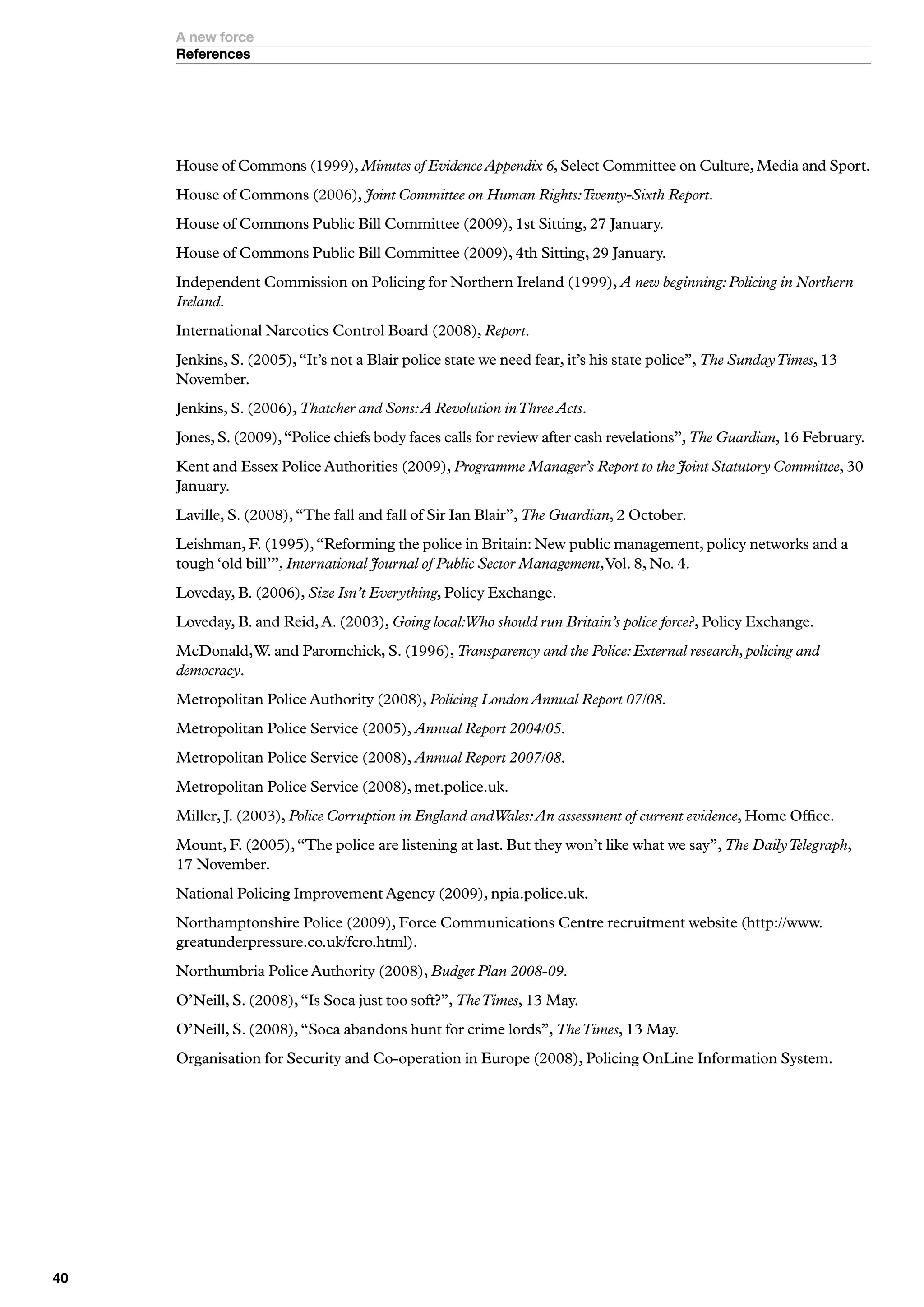

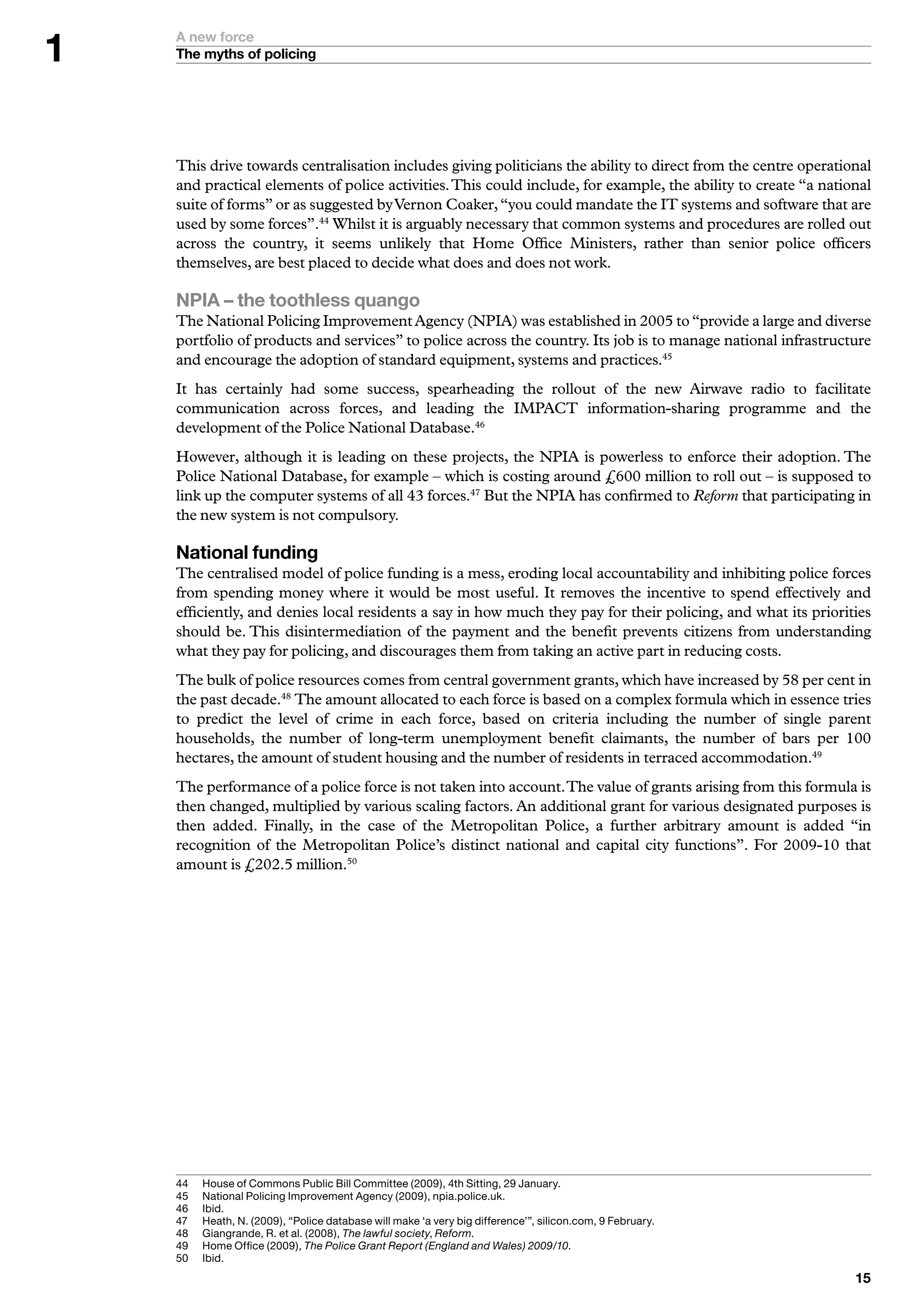

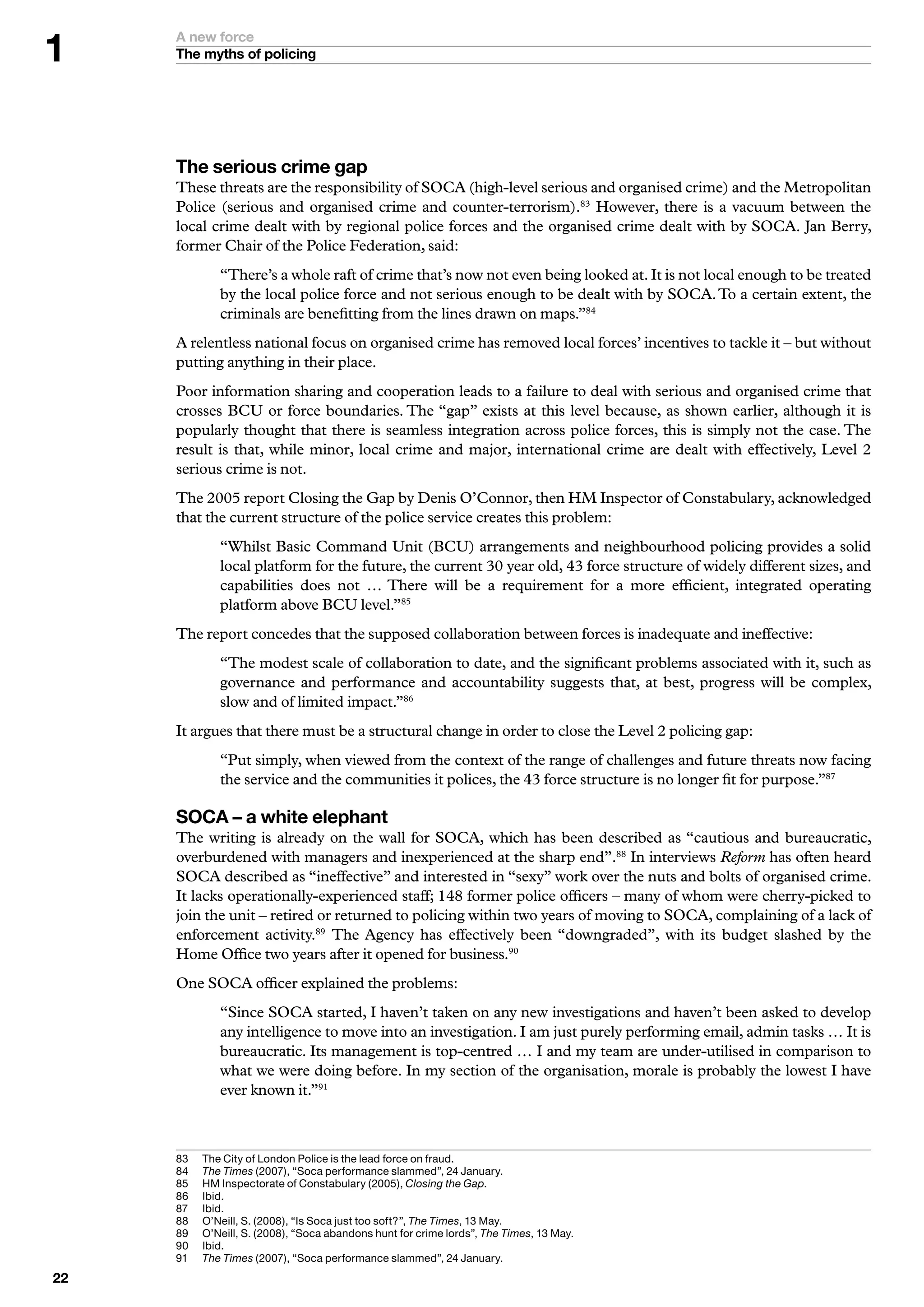

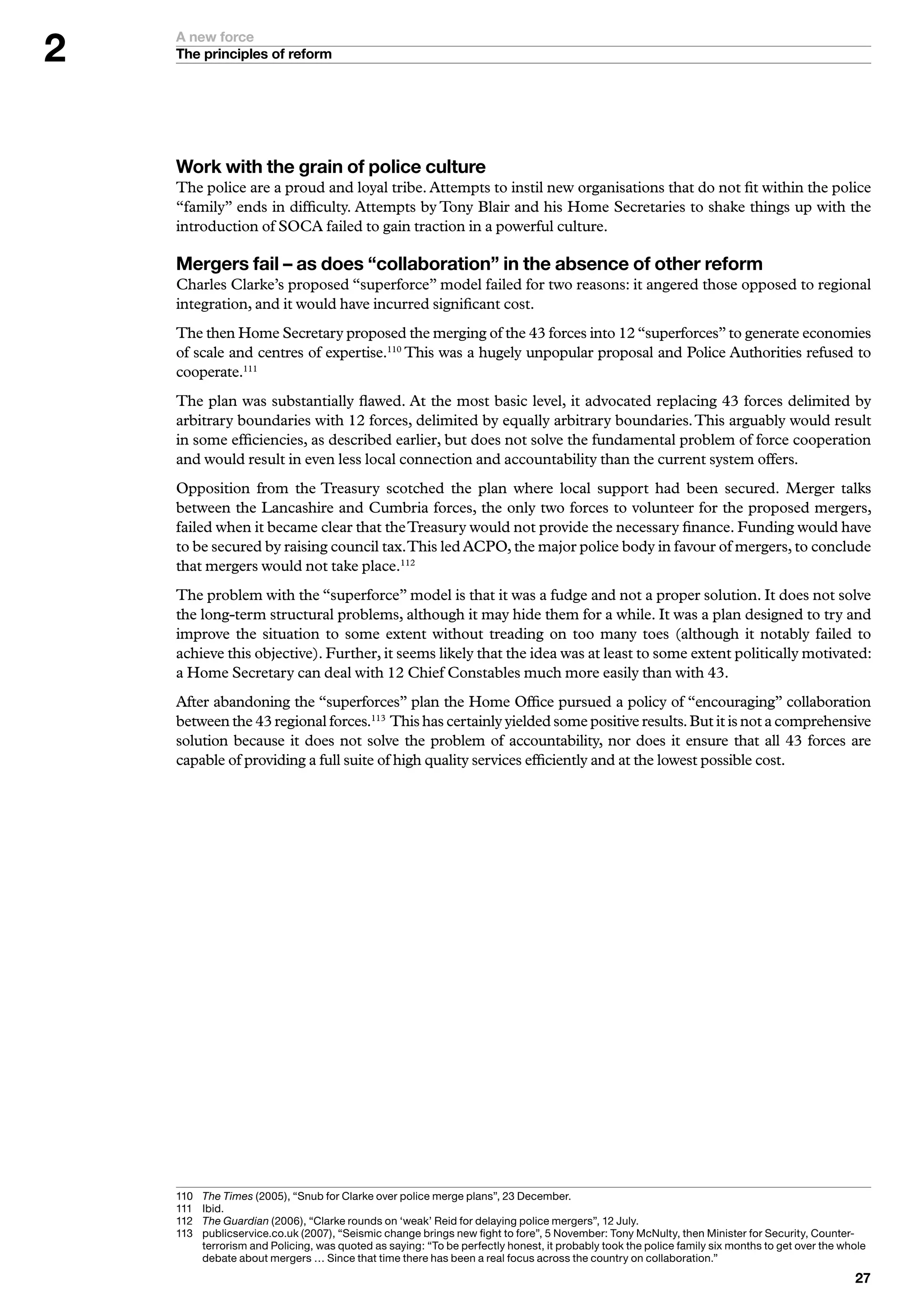

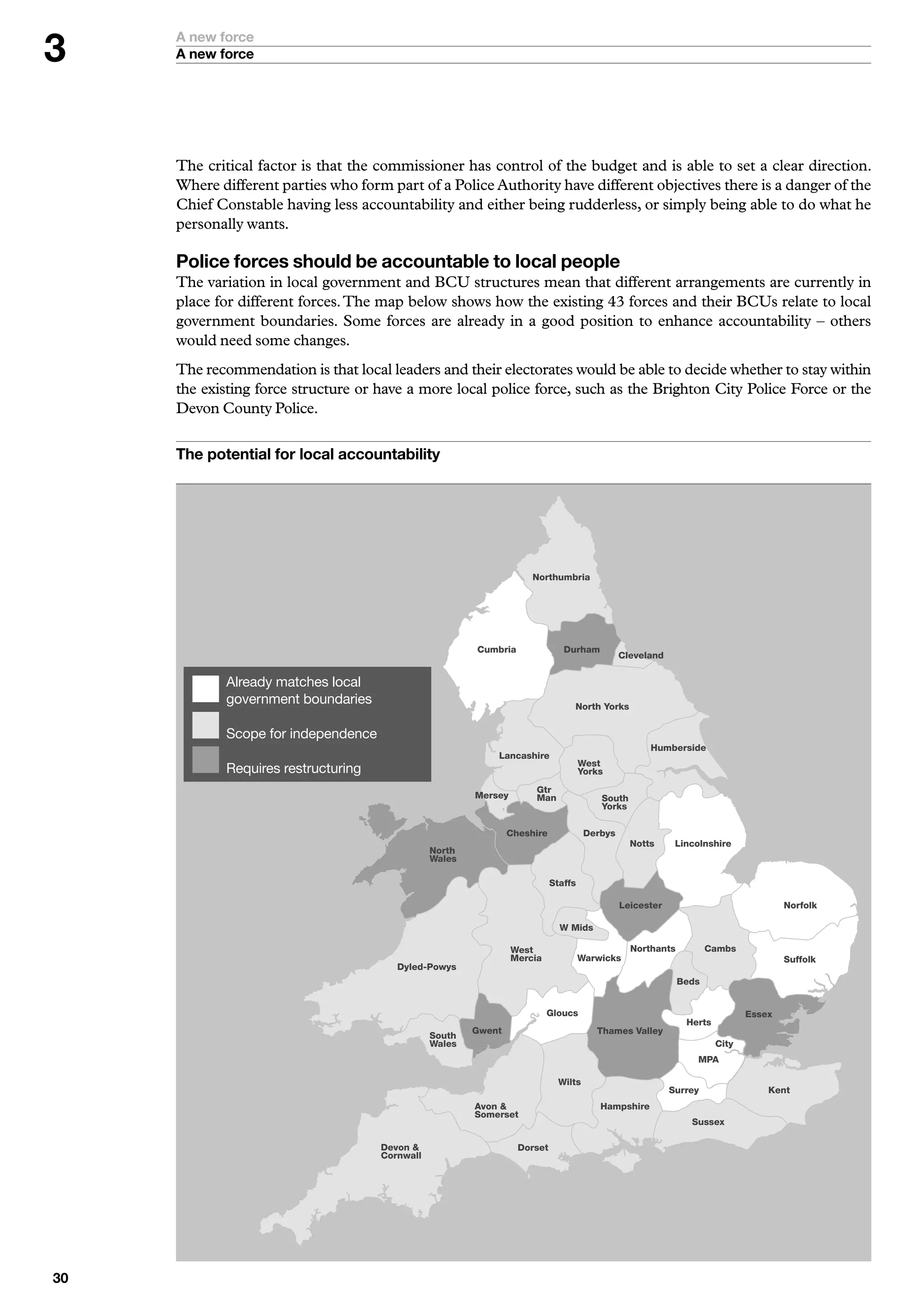

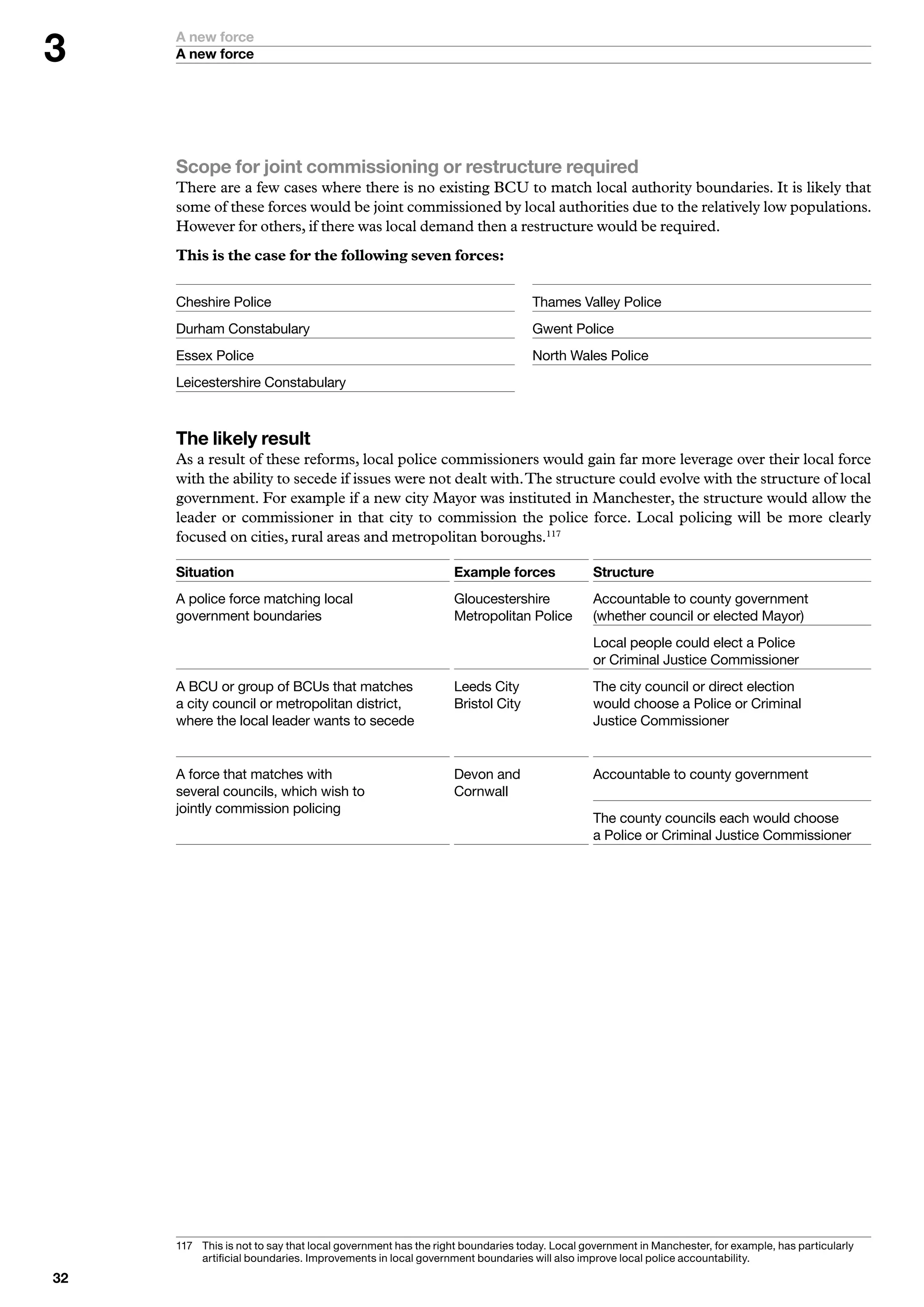

National Policing Plans

The National Policing Plans were the clearest expression of the policy of centralisation. Each Plan set out a

series of “priorities” for police forces to follow, supported by a greater number of targets, metrics or directives.

National Policing Plans

Home Office

Number of top level priorities Supporting targets

NPP 00-0 Four “directives”

e.g. “Tackle anti-social behaviour e.g. “Chief officers should work closely

and disorder” with local partners to tackle alcohol-related

crime effectively”

NPP 00-0 Seven (including two “themes”) performance metrics

e.g. “Combat serious and e.g. “New statutory indicator of sanction

organised crime, both across and detection rates for domestic rates for

within force boundaries” domestic burglary and violence against

the person by ethnicity of victim”

NPP 00-0 Five “Statutory Performance Indicators”

e.g. “Provide a citizen-focused police and metrics

service which responds to the needs e.g. “Using the British Crime Survey,

of communities and individuals … and [measure] the percentage of people who

inspires public confidence in the police” think their local police do a good job”

This proliferation of targeting and central direction inhibits local initiatives and priorities, leaving Chief

Constables unable to exercise their prerogative to direct their force.

Wresting more control

The current Policing and Crime Bill contains measures that will increase central control over forces through

new rules on collaboration. The Bill gives the Home Secretary the power not just to sanction and veto

collaboration agreements but to give guidance and directions on which forces should collaborate and how.42

Sir Norman Bettison, Chief Constable of the West Yorkshire Police, said:

“Our reading of the bill is that ultimately the Home Secretary, who currently has the power, will have

a mechanism by which to mandate collaboration.”43

9 P

olice Act 96: “The Secretary of State may cause a local inquiry to be held by a person appointed by him into any matter connected

with the policing of any area”.

0 P

olice Act 996: “The Secretary of State may by order determine objectives for the policing of the areas of all police authorities ... The

Secretary of State may direct police authorities to establish levels of performance [and] may impose conditions with which the

performance targets must conform, and different conditions may be imposed for different authorities.”

ome Office (2002), National Policing Plan 2003-06; Home Office (200), National Policing Plan 2004-07; Home Office (200), National

H

Policing Plan 2005-08. The Home Office states that the National Policing Plans should be “seen in the wider context” of the Home Office

Strategic Plans and policing policy papers. Bodies established since 200 include the Police Standards Unit, the National Policing

Improvement Agency and the Serious Organised Crime Agency.

2 P

olicing and Crime Bill 2008-09: “The Secretary of State may give chief officers or police authorities guidance about collaboration

agreements or related matters … In discharging their functions, chief officers and police authorities must have regard to the guidance.”

H

ouse of Commons Public Bill Committee (2009), st Sitting, 27 January.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/salesstrategydocumentation-12561338655456-phpapp01/75/Sales-Strategy-Documentation-15-2048.jpg)

![A new force

The myths of policing

Myth : The intelligence myth

The 43-force structure is intended to cope with crimes that cross force boundaries by sharing information

and intelligence. Roads policing, fraud and major incidents should see forces working together, sharing

resources and cooperating in the planning and implementation of strategy. There are some good examples

in the service of collaboration and joint arrangements.

Reality: fiefdoms resist action

Denuded of a real connection with the electorate and stymied by edicts from the Home Office, police chiefs

have sought to exert influence over the aspects of policing that are under their control. The reduction in the

number of police forces from 123 in 1964 to 43 today has, by definition, concentrated more power in the

hands of fewer people.54 The role was also strengthened through the 1994 Police and Magistrates Court

Act and the 1996 Police Act. Through these Acts the size of police authorities governing local police forces

was reduced from 35 members to 17.55 The Acts also abolished elections to Police Authorities and gave

Chief Constables control over police budgets.56

Poor inter-force intelligence

The Bichard Inquiry gave a damning verdict on the state of inter-force intelligence sharing. It declared that

“the importance everyone concerned professes to give intelligence was not borne out in reality”.57 There

was a devastating failure of the forces involved to share information:

“[Ian Huntley, the offender] had come to the attention of Humberside Police in relation to allegations

of eight sexual offences from 1995 to 1999 (and had been investigated in yet another). This

information had not emerged during the vetting check, carried out by Cambridgeshire constabulary

at the time of Huntley’s appointment to Soham Village College late in 2001.”58

Moreover, the IT systems which should have facilitated information-sharing were quite literally non-existent.59

The Inquiry called for the urgent implementation of a new system to enable forces to identify intelligence

that is held on an individual by another police force. This system, the IMPACT Nominal Index (INI) is

now in operation but is still missing tens of millions of records.60 The new Police National Database, which

should “replace the INI, as well as facilitate key links with other national information systems”, is yet to be

implemented.61 And, as we have seen, adoption of this database is not even compulsory.

Lack of agreement

The practical consideration of achieving agreement between 43 Chief Constables is problematic. In

interviews with Reform there has been widespread agreement that it is impossible to engage with a “seminar”

of 43 Chief Constables; indeed there is some thinking that at least part of the motivation behind Charles

Clarke’s “superforces” plan was the appeal of dealing with fewer Chief Constables.

However there are some good examples of collaboration in the service. Kent and Essex, for example, have

arrangements in a wide variety of areas. The forces have a joint procurement department and collaborate on

marine services, specialist vehicles, a helicopter and numerous back office functions.62 There are also examples

of cost-sharing between emergency services. Gloucestershire has one control room shared by the police, fire

and ambulance services. In addition to saving money, this tri-service arrangement facilitated an extremely

high level of cooperation during the 2007 floods. But while some inter-force collaboration is happening –

largely spurred on by the threat of police force mergers – it is not enough, and it is not happening fast enough.

5 ount, F. (2005), “The police are listening at last. But they won’t like what we say”, The Daily Telegraph, 7 November.

M

55 oveday, B. (2006), Size Isn’t Everything, Policy Exchange.

L

56 I

bid.

57 ichard, M. (200), The Bichard Inquiry Report.

B

58 I

bid.

59 I

bid: “Although national Information Technology (IT) systems for recording intelligence were part of the original National Strategy for

Police Information Systems (NSPIS) as long ago as 99, no such system exists even now. It was, in fact, formally abandoned in 2000

[and] there are still no firm plans for a national IT system in England and Wales.”

60 N

ational Policing Improvement Agency (2008): “As of January 2008, a total of 6 million records were held on the system and it is

estimated that, by 200, a total of 0 million records will be accessible.” (http://www.npia.police.uk/en/89.htm).

6 N

ational Policing Improvement Agency (2008) (http://www.npia.police.uk/en/895.htm).

62 ent and Essex Police Authorities (2009), Programme Manager’s Report to the Joint Statutory Committee, 0 January.

K](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/salesstrategydocumentation-12561338655456-phpapp01/75/Sales-Strategy-Documentation-18-2048.jpg)

![A new force

The myths of policing

Myth : The serious crime myth

When it launched in 2006 the Serious Organised Crime Agency (SOCA) was hailed as Britain’s FBI.70 It

was to “borrow intelligence-gathering techniques from MI5 and MI6 [and] poach methods from the world

of counter-terrorism”.71 According to its website:

“SOCA is an intelligence-led agency with law enforcement powers and harm reduction responsibilities.

Harm in this context is the damage caused to people and communities by serious organised crime.”72

While the police deal with local and more minor crime, SOCA takes responsibility at a national level for

serious and organised crime such as drug trafficking, people trafficking, money laundering and fraud.73

Reality: Serious crime remains a problem

Serious and organised crime presents a significant threat to the UK. The social and economic cost of serious

organised crime, including the costs of combating it, is estimated to be £20 billion.74

Drugs trafficking, people smuggling and gun crime are the principal elements of this serious crime, which is

referred to as Level 2 (regional) and Level 3 (national and international).75 Level 2 also includes other

issues such as homicide, riot control and contingencies such as flooding, major disease outbreaks and

strategic road policing.76

In 1998 the Home Office estimated that up to 1,420 women were trafficked into the UK. Just five years

later this estimate had risen to 4,000.77 The End Violence against Women Campaign has said the number is

now closer to 10,000.78

The price of cocaine has fallen by half in the last decade, and the International Narcotics Control Board

has warned that prices will continue to fall unless supply is curtailed.79 Heroin seized by the authorities in

2003-04 amounted to just 12 per cent of the overall market in Britain.80

The most recent SOCA Threat Assessment found that criminal gangs were succeeding in bringing in larger

quantities of firearms than had previously been assessed. This has fuelled street gun crime in three force

areas: London, Greater Manchester and the West Midlands.81

Internet crime is a growing phenomenon, which does not respect police force or even national boundaries.

One review estimated that there were around 35,000 identity thefts online in 2006, with an increase

expected in future years. There were estimated to be 207,000 cases of online financial fraud in 2006, up 35

per cent on the previous year. The review concluded: “It is clear that cybercrime is a pressing and prevalent

social problem.”82

70 ’Neill, S. (2008), “Soca abandons hunt for crime lords”, The Times, May.

O

7 ’Neill, S. (2008), “Is Soca just too soft?”, The Times, May.

O

72 S

erious Organised Crime Agency (2006), soca.gov.uk.

7 I

bid. The SOCA website lists the organisation’s focuses as drug trafficking, organised immigration crime, individual and private sector

fraud, money laundering and chemical suspicious activity reporting.

7 erious Organised Crime Agency (2008), The United Kingdom Threat Assessment of Serious and Organised Crime.

S

75 bid; HM Inspectorate of Constabulary (2005), Closing the Gap. Level 2 services are grouped under seven headings: counter terrorism

I

and extremism; serious organised and cross border crime; civil contingencies and emergency planning; critical incident management;

major crime (homicide); public order; and strategic roads policing. The National Intelligence Model (NIM) describes criminality as follows:

Level – local criminality that can be managed within a Basic Command Unit (BCU), Level 2 – cross border issues, usually of organised

criminals, major incident affecting more than one BCU, Level – Serious crime, terrorism operating at a national or international level.

76 M Inspectorate of Constabulary (2005), Closing the Gap.

H

77 ouse of Commons (2006), Joint Committee on Human Rights: Twenty-Sixth Report.

H

78 aves (2008), Eaves information sheet – sex trafficking, December.

E

79 I

nternational Narcotics Control Board (2008), Report; BBC News Online (2009), “Cocaine price ‘set to fall more’”, 9 February.

80 euter, P. and Stevens, A. (2007), An Analysis of UK Drug Policy, UK Drug Policy Commission.

R

8 erious Organised Crime Agency (2008), The United Kingdom Threat Assessment of Serious and Organised Crime.

S

82 afinski, S. (2006), UK Cybercrime report, Garlik.

F](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/salesstrategydocumentation-12561338655456-phpapp01/75/Sales-Strategy-Documentation-22-2048.jpg)

![A new force

The myths of policing

The missing Metropolitan Police mandate

As shown earlier, the Metropolitan Police already has responsibility for dealing with serious crime, counter-

terrorism and e-crime. The problem is that it does not have the formal control or resources to effectively

coordinate serious crime policing. Sir Paul Stephenson may be the de facto “national” Chief Constable, but

he is not in charge of everything he needs to be in charge of; he lacks a clearly defined mandate.

The Metropolitan Police is good at fighting serious and organised crime, and has the resources to do so.

The average number of criminal networks it disrupted rose from 3.4 per month in 2004/05 to 27.1 per

month in 2007/08.92 However outside London there is a gap – where the Metropolitan Police does not have

full control over serious crime fighting, but other forces do not have the resources and expertise to take on

the mantle themselves.

Going round in circles

Government’s focus on total crime numbers played a major role in destroying Level 2 policing. With three

key areas to focus on – response policing, neighbourhood policing and protective services (i.e. serious

crime) – Chief Constables found that they got no credit for work in the latter area. Accordingly it ceased to

be a priority. Resources were moved to a national level as Regional Crime Squads were replaced by the

National Crime Squad. As serious crime was no longer individual forces’ responsibility, the gap was allowed

to open.93

Now the HMIC series of “Level 2 Gap” reports has focused attention on the problem. As a result Regional

Intelligence Units have been established, at a substantial cost; Reform has been told that Gloucestershire

had to raise council tax by 52 per cent to fund the rebuilding of its protective services.

Continued confusion about serious crime fighting has created this gap in an essential area of policing

provision, wasting vast sums of money along the way. The lack of effective national coordination of serious

crime provision – and of a single point of leadership – will perpetuate this fudge.

Conclusion

SOCA has been downgraded.

Serious crime fighting is not effectively coordinated.

There continues to be a problem with serious crime, especially outside the London area.

92 etropolitan Police Service (2005), Annual Report 2004/05; Metropolitan Police Service (2008), Annual Report 2007/08.

M

9 B

BC News Online (998), “National squad targets top criminals”, March: “The [National Crime Squad] is taking over from the old

regional crime squads”.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/salesstrategydocumentation-12561338655456-phpapp01/75/Sales-Strategy-Documentation-24-2048.jpg)

![A new force

A new force

The Home Office to relinquish role in local policing

For the Home Secretary to get a better grip over serious and organised crime, she needs to relinquish

interference and targeting in the minutiae of local policing issues such as burglary and street crime. She also

needs to pass responsibility for issues such as interoperability to the professionals in the police force.

. Strengthen the role of the Metropolitan Police as the lead national

force on serious crime

One danger in public sector reform is, when faced with a weakness in provision, to create an entirely new

organisation where one is not needed. At worst, this duplicates effort and wastes resources without solving

the problem itself.

In retrospect the creation of SOCA is an example of this danger in practice. The gap in serious crime

provision that Denis O’Connor described in 2005 is real and remains.120 The Police Superintendents’

Association agrees that the current structure is outdated and not fit for purpose.121 But there was no need to

create a separate agency.

The creation of SOCA was the wrong answer to the right question. One organisation should be accountable

for serious, national crime. The Metropolitan Police already holds many of the responsibilities of a national

force, albeit with imperfect accountability and transparency. It commands the necessary respect from the

other police forces; Sir Paul Stephenson is accepted as the most senior police officer in the country.

The Metropolitan Police’s role should be enhanced and made transparent.

Metropolitan Police should have responsibility for serious crime at a national level

The Metropolitan Police should be answerable to the Home Secretary about whether serious and organised

crime is being effectively tackled. It should have a leadership role on all Level 2 and 3 serious and organised

crime across England and Wales.

SOCA should therefore cease to exist as a separate entity. Its responsibilities should be migrated to the

Metropolitan Police or the intelligence services as appropriate.

Giving the Metropolitan Police formal responsibility for leading national, serious crime fighting would

utilise its capabilities far better and provide local forces with the support they need.

This proposal has the advantage of allowing greater focus on performance and efficiency without requiring

a major restructuring of police forces and the consequent cost in morale and energy that this would cause.

National funding would continue to be provided, but rather than the “fits and starts” that have characterised

the setting up of agencies, it should be a continued stream overseen by the Home Secretary and scrutinised

by Parliament.

Improvements in local accountability will then be balanced by greater accountability for serious national crime.

20 M Inspectorate of Constabulary (2005), Closing the Gap.

H

2 olice Superintendents’ Association of England and Wales (2006), Press release: “Police Force Amalgamations – Wasted Opportunity”,

P

July: “[The] structure [of the police service] will remain rooted in the 970s when there were no mobile phones, no internet, no

cybercrime – we only had three television channels and the M25 had not been built. The world has changed and so must policing.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/salesstrategydocumentation-12561338655456-phpapp01/75/Sales-Strategy-Documentation-36-2048.jpg)