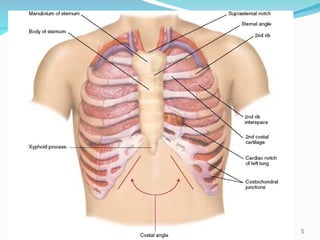

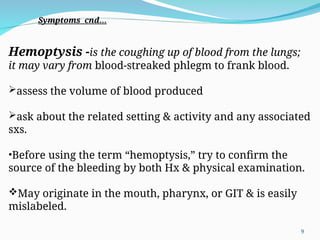

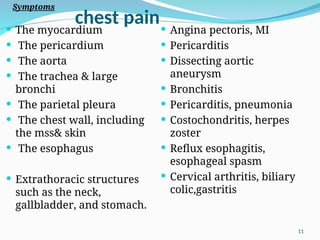

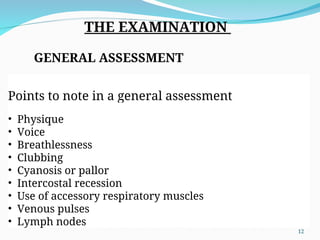

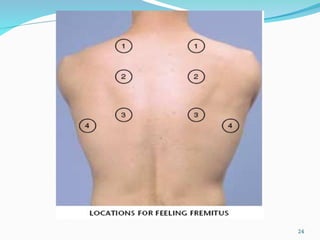

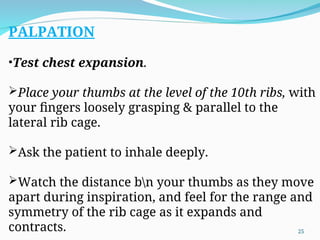

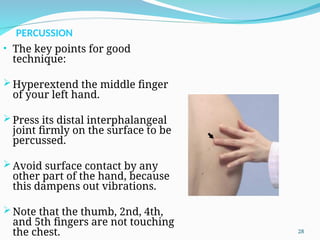

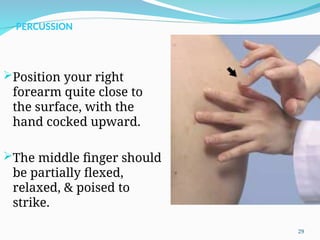

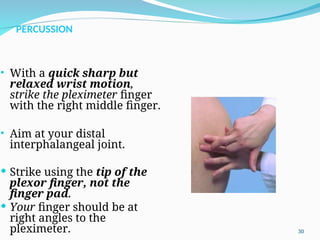

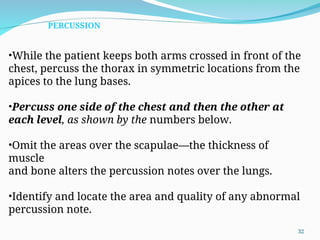

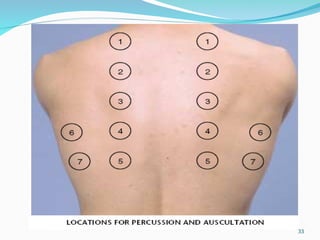

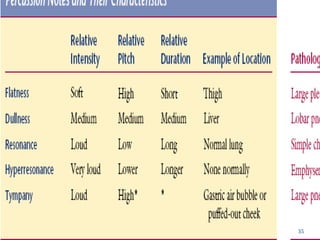

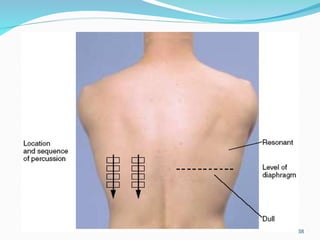

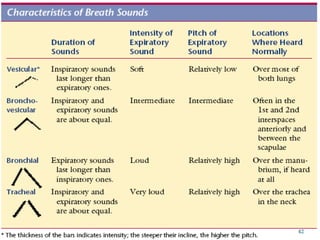

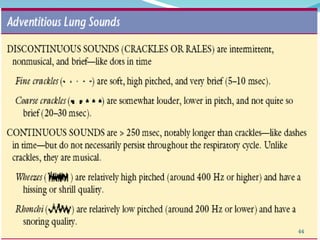

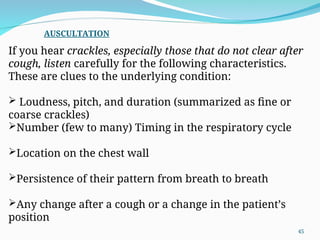

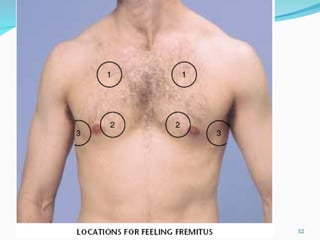

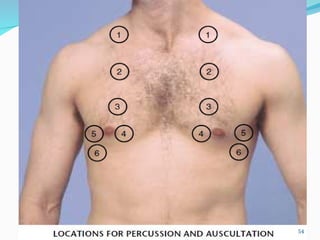

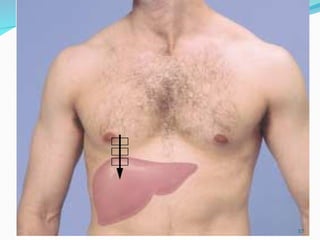

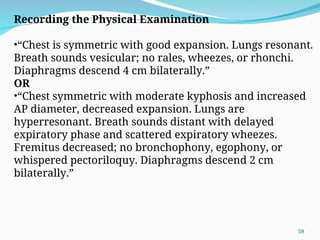

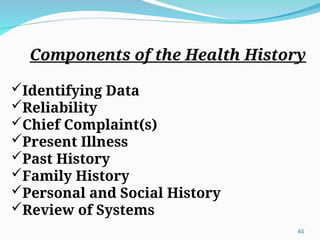

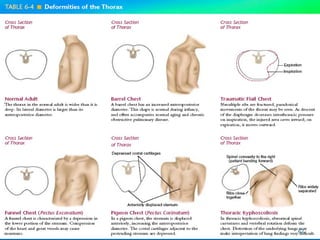

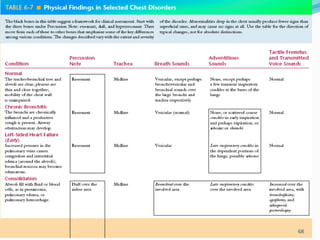

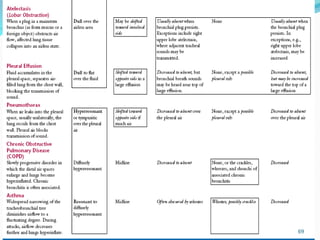

The document provides a comprehensive overview of assessing respiratory health, detailing common symptoms such as dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, and wheezing as well as the techniques for physical examination including inspection, palpation, percussion, and auscultation. It emphasizes understanding chest anatomy and the importance of observing and comparing findings on both sides of the chest. Additionally, it highlights the methods for evaluating breath sounds and identifying potential abnormalities.