The document discusses resource allocation in computer networks with an emphasis on survivability, particularly in scenarios involving enemy attacks. It contrasts centralized and distributed network structures, outlining the vulnerabilities and performance implications associated with each in terms of node and link destruction. Additionally, it explores design considerations for creating resilient systems that balance reliability against cost.

![high data rate links in emergencies.[2]

Satellites

The problem of building a reliable network using

satellites is somewhat similar to that of building a

communications network with unreliable links. When

a satellite is overhead, the link is operative. When a

satellite is not overhead, the link is out of service.

Thus, such links are highly compatible with the type

of system to be described.

Variable Data Rate Links

In a conventional circuit switched system each of the

tandem links requires matched transmission

bandwidths. In order to make fullest use of a digital

link, the post-error-removal data rate would have to

vary, as it is a function of noise level. The problem

then is to build a communication network made up of

links of variable data rate to use the communication

resource most efficiently.

Variable Data Rate Users

We can view both the links and the entry point nodes

of a multiple-user all-digital communications system

as elements operating at an ever changing data rate.

From instant to instant the demand for transmission

will vary.

We would like to take advantage of the average

demand over all users instead of having to allocate a

full peak demand channel to each. Bits can become a

common denominator of loading for economic

charging of customers. We would like to efficiently

Paul Baran‘62 On Distributed Communications Networks

ON A FUTURE SYST E M

DEVELOPMENT](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-38-320.jpg)

![high data rate links in emergencies.[2]

Satellites

The problem of building a reliable network using

satellites is somewhat similar to that of building a

communications network with unreliable links. When

a satellite is overhead, the link is operative. When a

satellite is not overhead, the link is out of service.

Thus, such links are highly compatible with the type

of system to be described.

Variable Data Rate Links

In a conventional circuit switched system each of the

tandem links requires matched transmission

bandwidths. In order to make fullest use of a digital

link, the post-error-removal data rate would have to

vary, as it is a function of noise level. The problem

then is to build a communication network made up of

links of variable data rate to use the communication

resource most efficiently.

Variable Data Rate Users

We can view both the links and the entry point nodes

of a multiple-user all-digital communications system

as elements operating at an ever changing data rate.

From instant to instant the demand for transmission

will vary.

We would like to take advantage of the average

demand over all users instead of having to allocate a

full peak demand channel to each. Bits can become a

common denominator of loading for economic

charging of customers. We would like to efficiently

Paul Baran‘62 On Distributed Communications Networks

ON A FUTURE SYST E M

DEVELOPMENT](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-39-320.jpg)

![A protocol that supports the sharing of resources that

exist in different packet switching networks is

presented. The protocol provides for variation in

individual network packet sizes, transmission failures,

sequencing, flow control, end-to-end error checking,

and the creation and destruction of logical process-

to-process connections. Some implementation issues

are considered, and problems such as internetwork

routing, accounting, and timeouts are exposed.

In the last few years considerable effort has been

expended on the design and implementation of

packet switching networks [1]-[7],[14],[17]. A principle

reason for developing such networks has been to

facilitate the sharing of computer resources. A packet

communication network includes a transportation

mechanism for delivering data between computers or

between computers and terminals. To make the data

meaningful, computer and terminals share a common

protocol (i.e, a set of agreed upon conventions).

Several protocols have already been developed for this

purpose [8]-[12],[16]. However, these protocols have

Vinton G. Cerf and Robert E. Kahn‘74 A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-55-320.jpg)

![In the last few years considerable effort has been

expended on the design and implementation of

packet switching networks [1]-[7],[14],[17]. A principle

reason for developing such networks has been to

facilitate the sharing of computer resources. A packet

communication network includes a transportation

mechanism for delivering data between computers or

between computers and terminals. To make the data

meaningful, computer and terminals share a common

protocol (i.e, a set of agreed upon conventions).

Several protocols have already been developed for this

purpose [8]-[12],[16]. However, these protocols have

Vinton G. Cerf and Robert E. Kahn‘74 A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

A protocol that supports the sharing of resources that

exist in different packet switching networks is

presented. The protocol provides for variation in

individual network packet sizes, transmission failures,

sequencing, flow control, end-to-end error checking,

and the creation and destruction of logical process-

to-process connections. Some implementation issues

are considered, and problems such as internetwork

routing, accounting, and timeouts are exposed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-56-320.jpg)

![In the last few years considerable effort has been

expended on the design and implementation of

packet switching networks [1]-[7],[14],[17]. A principle

reason for developing such networks has been to

facilitate the sharing of computer resources. A packet

communication network includes a transportation

mechanism for delivering data between computers or

between computers and terminals. To make the data

meaningful, computer and terminals share a common

protocol (i.e, a set of agreed upon conventions).

Several protocols have already been developed for this

purpose [8]-[12],[16]. However, these protocols have

Vinton G. Cerf and Robert E. Kahn‘74 A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

“A protocol that supports the

sharing of resources that exist in

different packet switching

networks is presented.”

A protocol that supports the sharing of resources that

exist in different packet switching networks is

presented. The protocol provides for variation in

individual network packet sizes, transmission failures,

sequencing, flow control, end-to-end error checking,

and the creation and destruction of logical process-

to-process connections. Some implementation issues

are considered, and problems such as internetwork

routing, accounting, and timeouts are exposed.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-57-320.jpg)

![A protocol that supports the sharing of resources that

exist in different packet switching networks is

presented. The protocol provides for variation in

individual network packet sizes, transmission failures,

sequencing, flow control, end-to-end error checking,

and the creation and destruction of logical process-

to-process connections. Some implementation issues

are considered, and problems such as internetwork

routing, accounting, and timeouts are exposed.

In the last few years considerable effort has been

expended on the design and implementation of

packet switching networks [1]-[7],[14],[17]. A principle

reason for developing such networks has been to

facilitate the sharing of computer resources. A packet

communication network includes a transportation

mechanism for delivering data between computers or

between computers and terminals. To make the data

meaningful, computer and terminals share a common

protocol (i.e, a set of agreed upon conventions).

Several protocols have already been developed for this

purpose [8]-[12],[16]. However, these protocols have

Vinton G. Cerf and Robert E. Kahn‘74 A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

packet fragmentation

transmission failures

sequencing

flow control

error checking

connection setup](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-58-320.jpg)

![incorporated. We envision it will occasionally be

invoked to allow HOST accommodation to

infrequent overdemands for limited buffer resources,

and otherwise not used much.

Any retransmission policy requires some means by

which the receiver can detect duplicate arrivals. Even

if an infinite number of distinct packet sequence

numbers were available, the receiver would still have

the problem of knowing how long to remember

previously received packets in order to detect

duplicates. Matters are complicated by the fact that

only a finite number of distinct sequence numbers are

in fact available, and if they are reused, the receiver

must be able to distinguish between new

transmissions and retransmissions.

A window strategy, similar to that used by the French

CYCLADES system (voie virtuelle transmission

mode [8]) and the ARPANET very distant HOST

connection [18]), is proposed here (see Fig. 10).

Suppose that the sequence number field in the

internetwork header permits sequence numbers to

range from 0 to n − 1. We assume that the sender will

not transmit more than w bytes without receiving an

acknowledgment. The w bytes serve as the window

(see Fig. 11). Clearly, w must be less than n. The rules

for sender and receiver are as follows.

Sender: Let L be the sequence number associated

with the left window edge.

1) The sender transmits bytes from segments whose

text lies between L and up to L + w − 1.

Vinton G. Cerf and Robert E. Kahn‘74 A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication

RETRANSMISSION A N D

DUPLICATE DETEC TI ON

NETWORK INTERCOMMUNICATION 643

SSIONANDDUPLICATE

DETECTION

e 100 percent reliable. We

d positive acknowledgment mecha-

TCP’s torecover from packet losses

other. A TCP transmits packets and

knowledgements) that are carried in

eam. If noacknowledgment for a

received, theTCP will retransmit.

that the HOST level retransmission

s described inthe following para-

called uponveryofteninpractice.

sts2 that individual networks can be

d without this feature. However, the

retransmissioncapabilitymakes it

om occasional network problems and

of HOST protocol strategies to be in-

ion it will occasionally be invoked to

dation to infrequent overdemandsfor

es, and otherwise not used much.

Left Window Edge

I

0 n-1a+w- 1a

1- window -4

I< packet sequence number space

-1

Fig. 10. The windowconcept.

Source

Address

I Address

Destination

I

6

7

8

9

10

Next Read Position

End ReadPosition

Timeout

Fig. 11. Conceptual TCBformat.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-72-320.jpg)

![On retransmission, the same packet might be broken

into three 200-byte packets going through a different

HOST. Since each byte has a sequence number, there

is no confusion at the receiving TCP. We leave for

later the issue of initially synchronizing the sender

and receiver left window edges and the window size.

Every segment that arrives at the destination TCP is

ultimately acknowlegded by returning the sequence

number of the next segment which must be passed to

the process (it may not yet have arrived).

Earlier we described the use of a sequence number

space and window to aid in duplicate detection.

Acknowledgments are carried in the process header

(see Fig. 6) and along with them there is provision for

a “suggested window” which the receiver can use to

control the flow of data from the sender. This is

intended to be the main component of the process

flow control mechanism. The receiver is free to vary

the window size according to any algorithm it desires

so long as the window size never exceeds half the

sequence number space.

This flow control mechanism is exceedingly powerful

and flexible and does not suffer from synchronization

troubles that may be encountered by incremental

buffer allocation schemes [9], [10]. However, it relies

heavily on an effective retransmission strategy. The

receiver can reduce the window even while packets

are en route from the sender whose window is

presently larger. The net effect of this reduction will

be that the receiver may discard incoming packets

(they may be outside the window) and reiterate the

Vinton G. Cerf and Robert E. Kahn‘74 A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication

NETWORK INTERCOMMUNICATION 643

SSIONANDDUPLICATE

DETECTION

e 100 percent reliable. We

d positive acknowledgment mecha-

TCP’s torecover from packet losses

other. A TCP transmits packets and

knowledgements) that are carried in

eam. If noacknowledgment for a

received, theTCP will retransmit.

that the HOST level retransmission

s described inthe following para-

called uponveryofteninpractice.

sts2 that individual networks can be

d without this feature. However, the

retransmissioncapabilitymakes it

om occasional network problems and

of HOST protocol strategies to be in-

ion it will occasionally be invoked to

dation to infrequent overdemandsfor

es, and otherwise not used much.

Left Window Edge

I

0 n-1a+w- 1a

1- window -4

I< packet sequence number space

-1

Fig. 10. The windowconcept.

Source

Address

I Address

Destination

I

6

7

8

9

10

Next Read Position

End ReadPosition

Timeout

Fig. 11. Conceptual TCBformat.

“a ‘suggested window’ which

the receiver can use to control

the flow of data from the sender.

This is intended to be the main

component of the process flow

control mechanism.”

FLOW CONTROL](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-73-320.jpg)

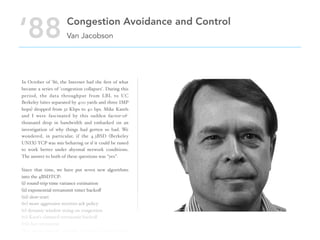

![(vii) fast retransmit

Our measurements and the reports of beta testers

suggest that the final product is fairly good at dealing

with congested conditions on the Internet.

This paper is a brief description of (i) - (v) and the

rationale behind them. (vi) is an algorithm recently

developed by Phil Karn of Bell Communications

Research, described in [KP87]. (vii) is described in a

soon-to-be-published RFC.

Algorithms (i) - (v) spring from one observation: The

flow on a TCP connection (or ISO TP-4 or Xerox NS

SPP connection) should obey a 'conservation of

packets' principle. And, if this principle were obeyed,

congestion collapse would become the exception

rather than the rule. Thus congestion control involves

finding places that violate conservation and fixing

them.

By 'conservation of packets' I mean that for a

connection 'in equilibrium', i.e., running stably with a

full window of data in transit, the packet flow is what

a physicist would call 'conservative': A new packet

isn't put into the network until an old packet leaves.

The physics of flow predicts that systems with this

property should be robust in the face of congestion.

Observation of the Internet suggests that it was not

particularly robust. Why the discrepancy?

There are only three ways for packet conservation to

fail:

1. The connection doesn't get to equilibrium, or

2. A sender injects a new packet before an old packet

has exited, or

3. The equilibrium can't be reached because of

Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-99-320.jpg)

![(vii) fast retransmit

Our measurements and the reports of beta testers

suggest that the final product is fairly good at dealing

with congested conditions on the Internet.

This paper is a brief description of (i) - (v) and the

rationale behind them. (vi) is an algorithm recently

developed by Phil Karn of Bell Communications

Research, described in [KP87]. (vii) is described in a

soon-to-be-published RFC.

Algorithms (i) - (v) spring from one observation: The

flow on a TCP connection (or ISO TP-4 or Xerox NS

SPP connection) should obey a 'conservation of

packets' principle. And, if this principle were obeyed,

congestion collapse would become the exception

rather than the rule. Thus congestion control involves

finding places that violate conservation and fixing

them.

By 'conservation of packets' I mean that for a

connection 'in equilibrium', i.e., running stably with a

full window of data in transit, the packet flow is what

a physicist would call 'conservative': A new packet

isn't put into the network until an old packet leaves.

The physics of flow predicts that systems with this

property should be robust in the face of congestion.

Observation of the Internet suggests that it was not

particularly robust. Why the discrepancy?

There are only three ways for packet conservation to

fail:

1. The connection doesn't get to equilibrium, or

2. A sender injects a new packet before an old packet

has exited, or

3. The equilibrium can't be reached because of

Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control

“(…) should obey a

‘conservation of packets’

principle”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-100-320.jpg)

![(vii) fast retransmit

Our measurements and the reports of beta testers

suggest that the final product is fairly good at dealing

with congested conditions on the Internet.

This paper is a brief description of (i) - (v) and the

rationale behind them. (vi) is an algorithm recently

developed by Phil Karn of Bell Communications

Research, described in [KP87]. (vii) is described in a

soon-to-be-published RFC.

Algorithms (i) - (v) spring from one observation: The

flow on a TCP connection (or ISO TP-4 or Xerox NS

SPP connection) should obey a 'conservation of

packets' principle. And, if this principle were obeyed,

congestion collapse would become the exception

rather than the rule. Thus congestion control involves

finding places that violate conservation and fixing

them.

By 'conservation of packets' I mean that for a

connection 'in equilibrium', i.e., running stably with a

full window of data in transit, the packet flow is what

a physicist would call 'conservative': A new packet

isn't put into the network until an old packet leaves.

The physics of flow predicts that systems with this

property should be robust in the face of congestion.

Observation of the Internet suggests that it was not

particularly robust. Why the discrepancy?

There are only three ways for packet conservation to

fail:

1. The connection doesn't get to equilibrium, or

2. A sender injects a new packet before an old packet

has exited, or

3. The equilibrium can't be reached because of

“(…) for a connection 'in

equilibrium', (…) the packet flow

is what a physicist would call

'conservative': A new packet

isn't put into the network until an

old packet leaves.”

Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control

“(…) should obey a

‘conservation of packets’

principle”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-101-320.jpg)

![Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control

is costly. But an exponential, almost regardless of its

time constant, increases so quickly that overestimates

are inevitable.

Without justification, I'll state that the best increase

policy is to make small, constant changes to the window

size:

On no congestion:

W~= W~_~+ ~ (~ << Wmo=)

where W,.,,a= is the pipesize (the delay-bandwidth prod-

uct of the path minus protocol overhead -- i.e., the

largest sensible window for the unloaded path). This

is the additive increase / multiplicative decrease policy

suggested in [JRC87] and the policy we've implemented

in TCP. The only difference between the two implemen-

tations is the choice of constants for d and u. We used

0.5 and I for reasons partially explained in appendix C.

A more complete analysis is in yet another in-progress

paper.

The preceding has probably made the congestion

control algorithm sound hairy but it's not. Like slow-

to slo

both c

by a ti

dow, t

depen

tives.

have b

tise th

descri

algori

Fig

nectio

thoug

delibe

nario

IMP en

in tran

4.3BSD

multa

at Ber

the bu

lead 12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-108-320.jpg)

![Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control

is costly. But an exponential, almost regardless of its

time constant, increases so quickly that overestimates

are inevitable.

Without justification, I'll state that the best increase

policy is to make small, constant changes to the window

size:

On no congestion:

W~= W~_~+ ~ (~ << Wmo=)

where W,.,,a= is the pipesize (the delay-bandwidth prod-

uct of the path minus protocol overhead -- i.e., the

largest sensible window for the unloaded path). This

is the additive increase / multiplicative decrease policy

suggested in [JRC87] and the policy we've implemented

in TCP. The only difference between the two implemen-

tations is the choice of constants for d and u. We used

0.5 and I for reasons partially explained in appendix C.

A more complete analysis is in yet another in-progress

paper.

The preceding has probably made the congestion

control algorithm sound hairy but it's not. Like slow-

to slo

both c

by a ti

dow, t

depen

tives.

have b

tise th

descri

algori

Fig

nectio

thoug

delibe

nario

IMP en

in tran

4.3BSD

multa

at Ber

the bu

lead 12

u = 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-109-320.jpg)

![Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control

(These are the first two terms in a Taylor series expan-

sion of L(t). There is reason to believe one might even-

tually need a three term, second order model, but not

until the Internet has grown substantially.)

When the network is congested, 7 must be large and

the queue lengths will start increasing exponentially, s

The system will stabilize only if the traffic sources throt-

tle back at least as quickly as the queues are growing.

Since a source controls load in a window-based proto-

col by adjusting the size of the window, W, we end up

with the sender policy

On congestion:

Wi = dWi_l (d < 1)

I.e., a multiplicative decrease of the window size (which

becomes an exponential decrease over time if the con-

gestion persists).

If there's no congestion, 7 must be near zero and the

load approximately constant. The network announces,

via a dropped packet, when demand is excessive but

utili

have

verg

able

widt

crea

T

tive

Wi =

will

thro

tedio

easy

to re

effec

9I

the s

will f

shrink

bottle

of co

move

is costly. But an exponential, almost regardless of its

time constant, increases so quickly that overestimates

are inevitable.

Without justification, I'll state that the best increase

policy is to make small, constant changes to the window

size:

On no congestion:

W~= W~_~+ ~ (~ << Wmo=)

where W,.,,a= is the pipesize (the delay-bandwidth prod-

uct of the path minus protocol overhead -- i.e., the

largest sensible window for the unloaded path). This

is the additive increase / multiplicative decrease policy

suggested in [JRC87] and the policy we've implemented

in TCP. The only difference between the two implemen-

tations is the choice of constants for d and u. We used

0.5 and I for reasons partially explained in appendix C.

A more complete analysis is in yet another in-progress

paper.

The preceding has probably made the congestion

control algorithm sound hairy but it's not. Like slow-

to slo

both c

by a ti

dow, t

depen

tives.

have b

tise th

descri

algori

Fig

nectio

thoug

delibe

nario

IMP en

in tran

4.3BSD

multa

at Ber

the bu

lead 12

u = 1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-110-320.jpg)

![Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control

(These are the first two terms in a Taylor series expan-

sion of L(t). There is reason to believe one might even-

tually need a three term, second order model, but not

until the Internet has grown substantially.)

When the network is congested, 7 must be large and

the queue lengths will start increasing exponentially, s

The system will stabilize only if the traffic sources throt-

tle back at least as quickly as the queues are growing.

Since a source controls load in a window-based proto-

col by adjusting the size of the window, W, we end up

with the sender policy

On congestion:

Wi = dWi_l (d < 1)

I.e., a multiplicative decrease of the window size (which

becomes an exponential decrease over time if the con-

gestion persists).

If there's no congestion, 7 must be near zero and the

load approximately constant. The network announces,

via a dropped packet, when demand is excessive but

utili

have

verg

able

widt

crea

T

tive

Wi =

will

thro

tedio

easy

to re

effec

9I

the s

will f

shrink

bottle

of co

move

is costly. But an exponential, almost regardless of its

time constant, increases so quickly that overestimates

are inevitable.

Without justification, I'll state that the best increase

policy is to make small, constant changes to the window

size:

On no congestion:

W~= W~_~+ ~ (~ << Wmo=)

where W,.,,a= is the pipesize (the delay-bandwidth prod-

uct of the path minus protocol overhead -- i.e., the

largest sensible window for the unloaded path). This

is the additive increase / multiplicative decrease policy

suggested in [JRC87] and the policy we've implemented

in TCP. The only difference between the two implemen-

tations is the choice of constants for d and u. We used

0.5 and I for reasons partially explained in appendix C.

A more complete analysis is in yet another in-progress

paper.

The preceding has probably made the congestion

control algorithm sound hairy but it's not. Like slow-

to slo

both c

by a ti

dow, t

depen

tives.

have b

tise th

descri

algori

Fig

nectio

thoug

delibe

nario

IMP en

in tran

4.3BSD

multa

at Ber

the bu

lead 12

u = 1

d = 0.5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-111-320.jpg)

![is costly. But an exponential, almost regardless of its

time constant, increases so quickly that overestimates

are inevitable.

Without justification, I'll state that the best increase

policy is to make small, constant changes to the window

size:

On no congestion:

W~= W~_~+ ~ (~ << Wmo=)

where W,.,,a= is the pipesize (the delay-bandwidth prod-

uct of the path minus protocol overhead -- i.e., the

largest sensible window for the unloaded path). This

is the additive increase / multiplicative decrease policy

suggested in [JRC87] and the policy we've implemented

in TCP. The only difference between the two implemen-

tations is the choice of constants for d and u. We used

to slow-start in addition to the above. But, because

both congestion avoidance and slow-start are triggered

by a timeout and both manipulate the congestion win-

dow, they are frequently confused. They are actually in-

dependent algorithms with completely different objec-

tives. To emphasize the difference, the two algorithms

have been presented separately even though in prac-

tise they should be implemented together. Appendix B

describes a combined slow-start/congestion avoidance

algorithm. 11

Figures 7 through 12 show the behavior of TCP con-

nections with and without congestion avoidance. Al-

though the test conditions (e.g., 16 KB windows) were

deliberately chosen to stimulate congestion, the test sce-

nario isn't far from common practice: The Arpanet

IMP end-to-end protocol allows at most eight packets

in transit between any pair of gateways. The default

The first thought is to use a symmetric, multiplicative

increase, possibly with a longer time constant, Wi =

bWi-1, 1 < b <1/d. This is a mistake. The result will

oscillate wildly and, on the average, deliver poor

throughput. There is an analytic reason for this but

it's tedious to derive. It has to do with that fact that it

is easy to drive the net into saturation but hard for

the net to recover (what [Kle76], chap. 2.1, calls the

rush-hour effect).9 Thus overestimating the available

bandwidth is costly. But an exponential, almost

regardless of its time constant, increases so quickly

that overestimates are inevitable.

Without justification, I'll state that the best increase

policy is to make small, constant changes to the

window size:

Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control

ADAPTING TO THE PATH :

CONGESTION AVOI DAN C E](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-112-320.jpg)

![is costly. But an exponential, almost regardless of its

time constant, increases so quickly that overestimates

are inevitable.

Without justification, I'll state that the best increase

policy is to make small, constant changes to the window

size:

On no congestion:

W~= W~_~+ ~ (~ << Wmo=)

where W,.,,a= is the pipesize (the delay-bandwidth prod-

uct of the path minus protocol overhead -- i.e., the

largest sensible window for the unloaded path). This

is the additive increase / multiplicative decrease policy

suggested in [JRC87] and the policy we've implemented

in TCP. The only difference between the two implemen-

tations is the choice of constants for d and u. We used

to slow-start in addition to the above. But, because

both congestion avoidance and slow-start are triggered

by a timeout and both manipulate the congestion win-

dow, they are frequently confused. They are actually in-

dependent algorithms with completely different objec-

tives. To emphasize the difference, the two algorithms

have been presented separately even though in prac-

tise they should be implemented together. Appendix B

describes a combined slow-start/congestion avoidance

algorithm. 11

Figures 7 through 12 show the behavior of TCP con-

nections with and without congestion avoidance. Al-

though the test conditions (e.g., 16 KB windows) were

deliberately chosen to stimulate congestion, the test sce-

nario isn't far from common practice: The Arpanet

IMP end-to-end protocol allows at most eight packets

in transit between any pair of gateways. The default

The first thought is to use a symmetric, multiplicative

increase, possibly with a longer time constant, Wi =

bWi-1, 1 < b <1/d. This is a mistake. The result will

oscillate wildly and, on the average, deliver poor

throughput. There is an analytic reason for this but

it's tedious to derive. It has to do with that fact that it

is easy to drive the net into saturation but hard for

the net to recover (what [Kle76], chap. 2.1, calls the

rush-hour effect).9 Thus overestimating the available

bandwidth is costly. But an exponential, almost

regardless of its time constant, increases so quickly

that overestimates are inevitable.

Without justification, I'll state that the best increase

policy is to make small, constant changes to the

window size:

Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control

“There is an analytic reason for

this but it's tedious to derive.”

ADAPTING TO THE PATH :

CONGESTION AVOI DAN C E](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-113-320.jpg)

![is costly. But an exponential, almost regardless of its

time constant, increases so quickly that overestimates

are inevitable.

Without justification, I'll state that the best increase

policy is to make small, constant changes to the window

size:

On no congestion:

W~= W~_~+ ~ (~ << Wmo=)

where W,.,,a= is the pipesize (the delay-bandwidth prod-

uct of the path minus protocol overhead -- i.e., the

largest sensible window for the unloaded path). This

is the additive increase / multiplicative decrease policy

suggested in [JRC87] and the policy we've implemented

in TCP. The only difference between the two implemen-

tations is the choice of constants for d and u. We used

to slow-start in addition to the above. But, because

both congestion avoidance and slow-start are triggered

by a timeout and both manipulate the congestion win-

dow, they are frequently confused. They are actually in-

dependent algorithms with completely different objec-

tives. To emphasize the difference, the two algorithms

have been presented separately even though in prac-

tise they should be implemented together. Appendix B

describes a combined slow-start/congestion avoidance

algorithm. 11

Figures 7 through 12 show the behavior of TCP con-

nections with and without congestion avoidance. Al-

though the test conditions (e.g., 16 KB windows) were

deliberately chosen to stimulate congestion, the test sce-

nario isn't far from common practice: The Arpanet

IMP end-to-end protocol allows at most eight packets

in transit between any pair of gateways. The default

The first thought is to use a symmetric, multiplicative

increase, possibly with a longer time constant, Wi =

bWi-1, 1 < b <1/d. This is a mistake. The result will

oscillate wildly and, on the average, deliver poor

throughput. There is an analytic reason for this but

it's tedious to derive. It has to do with that fact that it

is easy to drive the net into saturation but hard for

the net to recover (what [Kle76], chap. 2.1, calls the

rush-hour effect).9 Thus overestimating the available

bandwidth is costly. But an exponential, almost

regardless of its time constant, increases so quickly

that overestimates are inevitable.

Without justification, I'll state that the best increase

policy is to make small, constant changes to the

window size:

Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control

“There is an analytic reason for

this but it's tedious to derive.”

“Without justification, I’ll state

that the best increase policy

(…)”

ADAPTING TO THE PATH :

CONGESTION AVOI DAN C E](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-114-320.jpg)

![A reason for using 1⁄2 as the decrease term, as op-

posed to the 7/8 in [JRC87], was the following

handwaving: When a packet is dropped, you're either

starting (or restarting after a drop) or steady-state

sending. If you're starting, you know that half the

current window size 'worked', i.e., that a window's

worth of packets were exchanged with no drops

(slow-start guarantees this). Thus on congestion you

set the window to the largest size that you know

works then slowly increase the size. If the connection

is steady-state running and a packet is dropped, it's

probably because a new connection started up and

took some of your bandwidth. We usually run our

nets with p < 0.5 so it's probable that there are now

exactly two conversations sharing the bandwidth. I.e.,

you should reduce your window by half because the

bandwidth available to you has been reduced by half.

And, if there are more than two conversations sharing

the bandwidth, halving your window is conservative -

and being conservative at high traffic intensities is

probably wise.

Although a factor of two change in window size

seems a large performance penalty, in system terms

Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control

WINDOW ADJUSTMEN T POL ICY](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-115-320.jpg)

![A reason for using 1⁄2 as the decrease term, as op-

posed to the 7/8 in [JRC87], was the following

handwaving: When a packet is dropped, you're either

starting (or restarting after a drop) or steady-state

sending. If you're starting, you know that half the

current window size 'worked', i.e., that a window's

worth of packets were exchanged with no drops

(slow-start guarantees this). Thus on congestion you

set the window to the largest size that you know

works then slowly increase the size. If the connection

is steady-state running and a packet is dropped, it's

probably because a new connection started up and

took some of your bandwidth. We usually run our

nets with p < 0.5 so it's probable that there are now

exactly two conversations sharing the bandwidth. I.e.,

you should reduce your window by half because the

bandwidth available to you has been reduced by half.

And, if there are more than two conversations sharing

the bandwidth, halving your window is conservative -

and being conservative at high traffic intensities is

probably wise.

Although a factor of two change in window size

seems a large performance penalty, in system terms

Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control

“A reason for using 1/2 as the

decrease term (…) was the

following handwaving (…)”

WINDOW ADJUSTMEN T POL ICY](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-116-320.jpg)

![nets with p < 0.5 so it's probable that there are now

exactly two conversations sharing the bandwidth. I.e.,

you should reduce your window by half because the

bandwidth available to you has been reduced by half.

And, if there are more than two conversations sharing

the bandwidth, halving your window is conservative -

and being conservative at high traffic intensities is

probably wise.

Although a factor of two change in window size

seems a large performance penalty, in system terms

the cost is negligible: Currently, packets are dropped

only when a large queue has formed. Even with an

[ISO86] 'congestion experienced' bit to force senders

to reduce their windows, we're stuck with the queue

because the bottleneck is running at 100% utilization

with no excess bandwidth available to dissipate the

queue. If a packet is tossed, some sender shuts up for

two RTT, exactly the time needed to empty the

queue. If that sender restarts with the correct window

size, the queue won't reform. Thus the delay has been

reduced to minimum without the system losing any

bottleneck bandwidth.

The 1 packet increase has less justification than the

0.5 decrease. In fact, it's almost certainly too large. If

the algorithm converges to a window size of w, there

are O(w2) packets between drops with an additive

increase policy. We were shooting for an average drop

rate of < 1% and found that on the Arpanet (the worst

case of the four networks we tested), windows

converged to 8-12 packets. This yields I packet

increments for a 1% average drop rate.

Van Jacobson‘88 Congestion Avoidance and Control

“A reason for using 1/2 as the

decrease term (…) was the

following handwaving (…)”

“The 1-packet increase has less

justification than the 0.5

decrease. In fact, it's almost

certainly too large.”

WINDOW ADJUSTMEN T POL ICY](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-117-320.jpg)

![This paper is deliberately destructive. It sets out to

destroy an ideology that is blocking progress - the

idea that fairness between multiplexed packet traffic

can be achieved by controlling relative flow rates

alone. Flow rate fairness was the goal behind fair

resource allocation in widely deployed protocols like

weighted fair queuing (WFQ), TCP congestion

control and TCP-friendly rate control [8, 1, 11]. But it

is actually just unsubstantiated dogma to say that

equal flow rates are fair. This is why resource

allocation and accountability keep reappearing on

every list of requirements for the Internet

architecture (e.g. [2]), but never get solved. Obscured

by this broken idea, we wouldn’t know a good

solution from a bad one.

Controlling relative flow rates alone is a completely

impractical way of going about the problem. To be

realistic for large-scale Internet deployment, relative

flow rates should be the outcome of another fairness

mechanism, not the mechanism itself. That other

mechanism should share out the ‘cost’ of one user’s

actions on others—how much each user’s transfers

Bob Briscoe‘07 Flow Rate Fairness: Dismantling A Religion

INTRODUCTION](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-122-320.jpg)

![This paper is deliberately destructive. It sets out to

destroy an ideology that is blocking progress - the

idea that fairness between multiplexed packet traffic

can be achieved by controlling relative flow rates

alone. Flow rate fairness was the goal behind fair

resource allocation in widely deployed protocols like

weighted fair queuing (WFQ), TCP congestion

control and TCP-friendly rate control [8, 1, 11]. But it

is actually just unsubstantiated dogma to say that

equal flow rates are fair. This is why resource

allocation and accountability keep reappearing on

every list of requirements for the Internet

architecture (e.g. [2]), but never get solved. Obscured

by this broken idea, we wouldn’t know a good

solution from a bad one.

Controlling relative flow rates alone is a completely

impractical way of going about the problem. To be

realistic for large-scale Internet deployment, relative

flow rates should be the outcome of another fairness

mechanism, not the mechanism itself. That other

mechanism should share out the ‘cost’ of one user’s

actions on others—how much each user’s transfers

Bob Briscoe‘07 Flow Rate Fairness: Dismantling A Religion

INTRODUCTION](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-123-320.jpg)

![This paper is deliberately destructive. It sets out to

destroy an ideology that is blocking progress - the

idea that fairness between multiplexed packet traffic

can be achieved by controlling relative flow rates

alone. Flow rate fairness was the goal behind fair

resource allocation in widely deployed protocols like

weighted fair queuing (WFQ), TCP congestion

control and TCP-friendly rate control [8, 1, 11]. But it

is actually just unsubstantiated dogma to say that

equal flow rates are fair. This is why resource

allocation and accountability keep reappearing on

every list of requirements for the Internet

architecture (e.g. [2]), but never get solved. Obscured

by this broken idea, we wouldn’t know a good

solution from a bad one.

Controlling relative flow rates alone is a completely

impractical way of going about the problem. To be

realistic for large-scale Internet deployment, relative

flow rates should be the outcome of another fairness

mechanism, not the mechanism itself. That other

mechanism should share out the ‘cost’ of one user’s

actions on others—how much each user’s transfers

Bob Briscoe‘07 Flow Rate Fairness: Dismantling A Religion

“This paper is deliberately

destructive.”

INTRODUCTION](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-124-320.jpg)

![This paper is deliberately destructive. It sets out to

destroy an ideology that is blocking progress - the

idea that fairness between multiplexed packet traffic

can be achieved by controlling relative flow rates

alone. Flow rate fairness was the goal behind fair

resource allocation in widely deployed protocols like

weighted fair queuing (WFQ), TCP congestion

control and TCP-friendly rate control [8, 1, 11]. But it

is actually just unsubstantiated dogma to say that

equal flow rates are fair. This is why resource

allocation and accountability keep reappearing on

every list of requirements for the Internet

architecture (e.g. [2]), but never get solved. Obscured

by this broken idea, we wouldn’t know a good

solution from a bad one.

Controlling relative flow rates alone is a completely

impractical way of going about the problem. To be

realistic for large-scale Internet deployment, relative

flow rates should be the outcome of another fairness

mechanism, not the mechanism itself. That other

mechanism should share out the ‘cost’ of one user’s

actions on others—how much each user’s transfers

restrict other transfers, given capacity constraints.

Then flow rates will depend on a deeper level of

fairness that has so far remained unnamed in the

literature, but is best termed ‘cost fairness’.

It really is only the idea of flow rate fairness that

needs destroying—nearly ever ything we’ve

engineered can remain. The Internet architecture

Bob Briscoe‘07 Flow Rate Fairness: Dismantling A Religion

INTRODUCTION

“Obscured by this broken idea, we

wouldn’t know a good solution

from a bad one.”](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-150-320.jpg)

![increase with flow rate, but the shape and size of the

function relating the two (the utility function) is

unknown, subjective and private to each user. Flow

rate itself is an extremely inadequate measure for

comparing benefits: user benefit per bit rate might be

ten orders of magnitude different for different types

of flow (e.g. SMS and video). So different applications

might derive completely different benefits from equal

flow rates and equal benefits might be derived from

very different flow rates.

Turning to the cost of a data transfer across a

network, flow rate alone is not the measure of that

either. Cost is also dependent on the level of

congestion on the path. This is counter-intuitive for

some people so we shall explain a little further. Once

a network has been provisioned at a certain size, it

doesn’t cost a network operator any more whether a

user sends more data or not. But if the network

becomes congested, each user restricts every other

user, which can be interpreted as a cost to all - an

externality in economic terms. For any level of

congestion, Kelly showed [20] that the system is

optimal if the blame for congestion is attributed

among all the users causing it, in proportion to their

bit rates. That’s exactly what routers are designed to

do anyway. During congestion, a queue randomly

distributes the losses so all flows see about the same

loss (or ECN marking) rate; if a flow has twice the bit

rate of another it should see twice the losses. In this

respect random early detection (RED [12]) is slightly

fairer than drop tail, but to a first order

approximation they both meet this criterion.

So in networking, the cost of one flow’s behaviour

Bob Briscoe‘07 Flow Rate Fairness: Dismantling A Religion

COST, NOT BENEFIT](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-153-320.jpg)

![increase with flow rate, but the shape and size of the

function relating the two (the utility function) is

unknown, subjective and private to each user. Flow

rate itself is an extremely inadequate measure for

comparing benefits: user benefit per bit rate might be

ten orders of magnitude different for different types

of flow (e.g. SMS and video). So different applications

might derive completely different benefits from equal

flow rates and equal benefits might be derived from

very different flow rates.

Turning to the cost of a data transfer across a

network, flow rate alone is not the measure of that

either. Cost is also dependent on the level of

congestion on the path. This is counter-intuitive for

some people so we shall explain a little further. Once

a network has been provisioned at a certain size, it

doesn’t cost a network operator any more whether a

user sends more data or not. But if the network

becomes congested, each user restricts every other

user, which can be interpreted as a cost to all - an

externality in economic terms. For any level of

congestion, Kelly showed [20] that the system is

optimal if the blame for congestion is attributed

among all the users causing it, in proportion to their

bit rates. That’s exactly what routers are designed to

do anyway. During congestion, a queue randomly

distributes the losses so all flows see about the same

loss (or ECN marking) rate; if a flow has twice the bit

rate of another it should see twice the losses. In this

respect random early detection (RED [12]) is slightly

fairer than drop tail, but to a first order

approximation they both meet this criterion.

So in networking, the cost of one flow’s behaviour

Bob Briscoe‘07 Flow Rate Fairness: Dismantling A Religion

“(…) if the network becomes

congested, each user restricts every

other user, which can be

interpreted as a cost to all - an

externality in economic terms.”

COST, NOT BENEFIT](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pwl2-160607180433/85/Resource-Allocation-in-Computer-Networks-154-320.jpg)