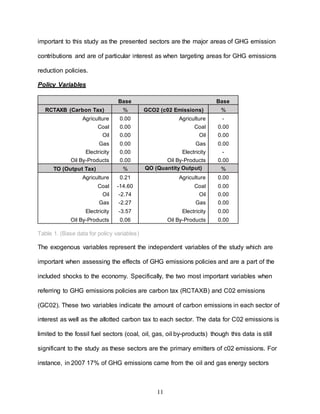

This document provides a summary of a research paper analyzing the effects of environmental policy on the economy. Specifically, it examines implementing a carbon tax and reducing output subsidies for fossil fuels in Canada and surrounding regions. It finds that a carbon tax is effective at reducing greenhouse gas emissions with a slight positive impact on the economy. Emissions reductions also occur through carbon trading, which allows countries to trade emissions quotas. The research utilizes a GTAP model to analyze the economic and environmental impacts of different greenhouse gas policies.