REP103 Amounts, impacts ,implications illegal timber removal

- 1. SOUTH and CENTRAL KALIMANTAN PRODUCTION FOREST PROJECT Jalan A. Yani, No. 37 (km35), Banjarbaru 70711, Indonesia Tel. (62) 0511 781 975 – 979, Fax: (62) 0511 781 613 EUROPEAN COMMISSION – INDONESIA FOREST PROGRAMME Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT. AYI forest concession, 1999-2002 Report No. 103 March 2002

- 2. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 i PREFACE The South and Central Kalimantan Production Forest Project (SCKPFP) is a technical co-operation project jointly funded, in terms of the financing memorandum ALA/95/18, by the European Commission and by the Government of the Republic of Indonesia through the Ministry of Forestry and Estate Crops (MoFEC). This report has been completed in accordance with the project Phase I Overall Work Plan (OWP) and in part fulfilment of Activity 1.9, “To investigate and develop proposals for resolving the current illegal logging activities in the concession areas”, and Activity 4.1, “To identify timber resources and products in the province”, and Activity 6.4 , “To recommend any improvement to increase the capacity of forest protection” , to achieve Result 1 “SFM plans and practices that incorporate ITTO guidelines implemented in the production forest of the pilot sites”, and Result 4 “Strategy developed to balance sustainable supply and demand of raw material for the forest industry, incorporating opportunities to create added value from forest products processing”, and Result 6 “The forest ecosystem and associated ecosystems within the project sites managed to maintain viability and diversity” to realise the three-year project Phase I purpose, which is “SFM model developed that incorporates the ITTO guidelines and principles developed and implemented in the forestry operation of Aya Yayang and a central Kalimantan pilot concession.” This report has been prepared with financial assistance from the Commission of the European Communities. The opinions, views and recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and in no way reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The report has been prepared by: • Junaidi Payne (Ecologist) The report is acknowledged and approved for circulation by the Project Co- Directors when duly signed below. Banjarbaru, March 2002 ……………………………… Dr. John Tew International Co-Director ……………………………… Dr. Silver Hutabarat National Co-Director

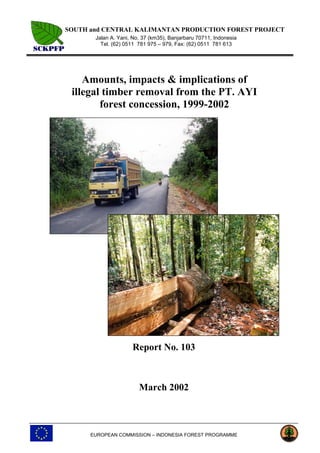

- 3. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks go to the families who conducted the traffic monitoring on the PT AYI road, at Mahe and Muara Uya; the various people who supplied information and ideas in upper Tabalong; and SCKPFP specialists who provided comments for improvement of this report. Front cover : (above) Truck loaded with about 13 m3 of sawn timber from the PT AYI area, on the road between Bentot and Kambitin. (below) One of about six mature keruing trees (Dipterocarpus species) felled across the main trail in the PT AYI Arboretum in August 2001. Apart from destroying the most accessible remaining stand of mature keruing trees in upper Tabalong, about 50% of potential wood was wasted.

- 4. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 iii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report seeks to assess the amounts, impacts and implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI production forest concession area, upper Tabalong, South Kalimantan. Sale of wood products not controlled by government has a long history in Tabalong. However, felling of trees by operators other than PT AYI within the PT AYI concession for commercial sale of timber is clearly illegal under current law. The information used in the report consists of two sorts : SCKPFP Ecologist notes on numerous field observations and discussions during the period June 1999 – February 2002, and monitoring traffic out of the upper Tabalong forest area during late October 2001 – early March 2002. The great majority of illegal timber felled within the PT AYI area passes through one of three locations : (A) the PT AYI timber extraction road between Lalap and Bentot, (B) the lower Tabalong Kiwa River at Mahe, and (C) the road between Binjai (on the Ayu River) and Muara Uya. Eight types of timber are taken by illegal operators, mostly the same dipterocarp trees taken by PT AYI. Ulin is not taken by PT AYI. Except for jabon (which is removed as round logs) and some ulin (cut into roof shingles), trees felled by illegal operators are sawn into beams (typically 400 x 30 x 15 cm) or planks, using a chainsaw, in the forest. Each sawn piece is dragged by one person to a river or roadside for transportation out of the PT AYI concession area. The furthest distance that trees are felled from a road or river in a straight line is just over 1 km, perhaps up to 2 km distance on the ground. Sawn timber is tied together to form rafts for transportation by river. Light-weight wooden floats are tied to dense wood. The majority of transportation by river is done during rainy periods when water levels are high. Sawn timber is loaded manually on to trucks for transportation by road. Almost all trucks used are Mitsubishi Colts, with about 95% being 120 horse-power (which can theoretically take a maximum load of about 8 m3) and the balance 135 horse- power (which can theoretically take a maximum load of about 10 m3). Sawn ulin wood and small quantities of planks of other timbers are transported by four-wheel drive pickups and Toyota Hardtops. The main timber source areas within the PT AYI area can be divided into three Zones, whereby the great majority of that timber then flows through three “bottleneck” locations A, B and C described above. The majority of illegal operators appear to originate from villages between Tanjung town and Solan, along the Tabalong Kanan River, with ages ranging from about 14 years to early 50’s.

- 5. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 iv It is estimated that on any one day, nearly 300 men and youths may be engaged in unlicensed felling, sawing and manual transportation, and up to 60 involved removing timber by truck from the PT AYI forest area. Currently, the only factors locally within upper Tabalong limiting the amounts of trees felled appear to be the number of chainsaws available, the extent of roads accessible to trucks within the PT AYI area and distance from a road. It is estimated that 2,500 m3 of timber per month was removed from Zone A during the 3-month monitoring period, based on an average of 10.2 truck loads per day and 8 m3 per load. It is estimated that on average 60 m3/month is removed from Zone B and 500 m3/month from Zone C. It is believed that the information obtained for Zones A and C covered months where timber volumes removed were slightly less than average. Thus, at least 3,000 m3 of timber is removed per month illegally from the PT AYI concession, equivalent to a minimum of 36,000 m3 per year. It is estimated that the “annual cut” from the PT AYI concession done by illegal operators is at least 72,000 m3, because there is a roughly 50% conversion ratio (about half the amount of tree trunk which could be extracted by legal operators with skidders and sold to mills is left in the forest by illegal operators). This amount is well above the maximum legal allowable annual cut of PT AYI and above the estimated natural annual growth of commercial timber trees. It is estimated that at least 10,000 trees were felled illegally each year in the PT AYI area during the period 1999 – 2002, assuming that an average tree represented 7 m3 of timber. Amounts of ulin appear to have declined significantly over the survey period. Jabon was never seen felled prior to early July 2000, after which is became a favoured species. The trend during 1999 – 2002 was towards taking smaller trees, as all large trees have been felled in accessible areas other than newly-opened PT AYI felling blocks. In 1999, almost all trees felled were large above 80 cm dbh. 2001 was the first year when meranti trees less than 50 cm dbh were seen felled. In the absence of law enforcement measures, it is predicted that illegal felling will continue and become progressively more damaging to prospects for forest recovery, with smaller trees and additional types taken, and intense pressure on each new PT AYI felling block. The immediate local environmental impacts are normally much less severe with illegal logging than with logging by PT AYI, largely because bulldozers are normally not used and sawn timber hauled by illegal operators results in less damage done by the timber to soil and adjacent vegetation. Also, the wood, bark and sawdust left around felling sites is probably beneficial ecologically in maintenance of soil organic matter.

- 6. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 v However, the impact of illegal logging on prospects for forest recovery overall is severely negative for at least seven reasons : (1) commercial seed-producing trees are being eliminated; (2) the forest is becoming lower in stature and more open, like a secondary forest; (3) illegal operators represent a major potential source of forest fire during dry periods; (4) illegal operators re-open roads and trails that should be left to regenerate, thereby re-exposing soil to erosion and introducing garbage; (5) illegal operators fell defective trees with holes and hollows that represent nesting and breeding sites for wildlife; (6) illegal operators fell all trees yielding commercial timber within a distance of at least 1 km of all larger rivers; and (7) illegal logging near major roads may act as an incentive for people to make ladangs. Due to various prevailing factors, the relevant authorities seem reluctant to “take repressive action” against illegal operators. Involvement in the various aspects of the illegal timber business represents one of the few opportunities for cash-generating work in the Tabalong district, especially for young men. However, many aspects of employment currently linked to illegal timber, other than obtaining the illegal timber per se, could be sustained if large volumes of plantation wood were available. Sustainable forest management (SFM) in the PT AYI HPH concession area is not possible if the amount and extent of illegal logging prevailing during August 1999 – February 2002 continues. The best way to maximise prospects for long-term sustainability of the production forests of upper Tabalong may be to : - reduce the access that illegal operators have to forest (e.g. by arranging the allocation of RKL and RKT to minimise the extent of accessible roads at any one time, and make bridges and culverts of timber species that will rot and collapse soon after their usefulness to PT AYI has ended); - devote serious attention to developing large areas of tree plantations on already deforested land (starting with formal resolution of land tenure); and - concentrate efforts on diversifying and expanding employment opportunities generally in Tabalong district. But in the absence of any law enforcement against illegal operations, these measures may be too little, too late.

- 7. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 vi RINGKASAN (INDONESIAN SUMMARY) Laporan ini mencoba untuk menaksir jumlah, dampak dan implikasi yang ditimbulkan oleh pengangkutan atau perpindahan kayu liar dari areal HPH PT. AYI, Hulu Tabalong, Kalimantan Selatan. Penjualan produk kayu yang tidak terkontrol oleh pemerintah di Kabupaten Tabalong, memiliki latar belakang yang panjang. Bagaimanapun, penebangan pohon oleh para penebang selain karyawan PT AYI di dalam kawasan HPH PT AYI untuk dijual secara komersial, dengan jelas merupakan tindakan illegal menurut hukum yang berlaku. Informasi yang digunakan dalam laporan ini terdiri atas dua macam: catatan dari ahli ekologi SCKPFP yang diperoleh dari sejumlah penelitian dilapangan dan diskusi selama periode waktu Juni 1999 sampai dengan Februari 2002, dan pengamatan terhadap peredaran kayu tebangan di areal hutan Hulu Tabalong selama akhir bulan Oktober 2001 sampai dengan awal Maret 2002. Penebangan kayu illegal sebagian besar terjadi di dalam areal PT. AYI melalui satu dari tiga lokasi yang ada yaitu: (A) jalan antara Lalap dan Bentot dimana PT. AYI melakukan pemungutan kayu, (B) di Hilir sungai Tabalong Kiwa, tepatnya di Mahe, dan (C) jalan antara Binjai (di sungai Ayu) dan Muara Uya. Delapan jenis kayu yang diambil oleh penebang liar, hampir semuanya merupakan jenis pohon dipterocarp yang sama diambil oleh PT. AYI. Kecuali jenis kayu Ulin yang tidak diambil oleh PT AYI. Kecuali untuk jabon (yang diangkut dalam bentuk kayu bulat) dan beberapa ulin (berupa potongan sirap), pohon yang ditebang oleh para petugas illegal itu kemudian digergaji menjadi balok-balok (umumnya berukuran 400 x 30 x 15 cm) atau menjadi papan, dengan menggunakan chainsaw di hutan. Satu orang yang bertugas menarik potongan-potongan kayu tadi ke sungai atau ke jalan untuk dibawa keluar dari areal HPH PT. AYI. Jarak dari tempat penebangan ke jalan atau sungai bila ditarik garis lurus adalah maksimum 1 km lebih, mungkin sekitar 2 km jarak lapangan. Balok-balok itu disatukan, diikat menjadi rakit dan dikirim melalui sungai. Kayu- kayu yang berat diapungkan bersama kayu ringan dan dilarutkan. Umumnya, pengiriman melalui sungai dilakukan selama musim hujan pada saat air sedang dalam. Balok-balok tadi di masukkan ke dalam truk-truk secara manual dan dikirim melalui jalur darat. Hampir semua truk yang digunakan adalah Colt Mitsubishi yang berkekuatan sekitar 95%nya dengan kekuatan 120 tenaga kuda (yang secara teorinya mampu mengangkut 8 m3) dan sisanya berkekuatan 135 tenaga kuda (yang secara toerinya mampu mengangkut maksimum 10 m3). Sedangkan untuk kayu ulin dan papan yang telah digergaji diangkut dengan menggunakan mobil pick up kecil dan Toyota Hardtop. Areal penghasil balok terbesar yang ada di wilayah PT. AYI dapat dibedakan menjadi tiga bagian/wilayah dimana penghasil kayu utamanya tersebar di tiga lokasi padat yaitu A, B dan C seperti yang telah dijelaskan di atas. Sebagian besar para penebang liar itu berasal dari Kabupaten Tabalong dengan usia sekitar 14 tahun sampai dengan 50 tahunan.

- 8. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 vii Diperkirakan dalam satu harinya sekitar 300 orang dewasa dan remaja yang terlibat di dalam penebangan tak berijin, penggergajian serta pengiriman local, dan hingga 60 orang yang terlibat dalam pengangkutan balok dengan menggunakan truk dari areal hutan PT. AYI. Sekarang ini, hanya faktor lokal di Hulu Tabalong yang membatasi penebangan pohon tampaknya bergantung pada jumlah chainsaw, panjang jalan yang dapat diakeses serta jarak dari tepi jalan. Di perkirakan sekitar 2,500 m3 kayu perbulan diangkut dari Zona A selama 3 bulan masa pengamatan, berdasarkan perkiraan rata-rata bahwa 10.2 truk per hari dengan muatan 8 m3 satu kali angkut. Diperkirakan rata-rata 60 m3/bulannya dipindahkan dari Zona B dan sebanyak 500 m3/bulannya yang dipindahkan dari Zona C. Sangat dipercaya bahwa berdasarkan informasi yang dikumpulkan dari Zona A dan Zona C selama beberapa bulan jumlah kayu yang dikeluarkan tampaknya kurang dari jumlah rata-ratanya. Dengan demikian setidaknya sekitar 3,000 m3 balok/bulannya dipindahkan secara illegal dari areal HPH PT. AYI, atau setara dengan 36,00 m3 pertahunnya. Diperkirakan bahwa “tebangan tahunan” yang dilakukan oleh penebang liar di kawasan HPH PT. AYI mencapai 72,000 m3, sebab diperkirakan terdapat rasio konversi sebesar 50% (sekitar setengah dari jumlah batang pohon yang dipanen oleh penebang liar dengan penyarad dan dijual ke penggergajian- penggergajian telah ditinggalkan di hutan oleh para penebang liar). Jumlah ini adalah diatas jatah maksimum dari jatah tebangan tahunan PT. AYI, dan diatas perkiraan pertumbuhan tahunan alami pohon-pohon komersial. Diperkirakan setidaknya 10,000 pohon ditebangi secara liar di kawasan PT. AYI untuk tiap tahunnya selama periode waktu 1999-2002, dengan asumsi bahwa rata-rata pohon menghasilkan 7 m3 kayu. Jumlah ulin terlihat menurun secara signifikan pasca survei. Jabon yang tampaknya tidak pernah ditebang sebelum Juli 2000 menjadi jenis yang disukai setelah kurun waktu tersebut. Kecendrungan penebangan selama 1999-2002 adalah terhadap pohon-pohon berdiameter kecil, karena semua pohon berdiameter besar pada kawasan yang dapat diakses telah ditebang kecuali pada petak tebangan PT AYI yang baru dibuka. Pada 1999, hampir semua pohon yang ditebang berdiameter lebih dari 80 cm. Tahun 2001 merupakan tahun pertama dimana pohon meranti dengan diameter kurang dari 50 cm terlihat ditebang. Penilaian terhadap keberadaaan penegakkan hukum, diperkirakan bahwa penebangan liar akan terus berlanjut dan lebih menimbulkan kerusakan terhadap percepatan pemulihan hutan. Diperkirakan pohon yang berdiameter lebih kecil serta jenis yang lain merupakan jenis-jenis yang akan dipanen pada masa akan datang. Demikian pula tekanan terhadap blok-blok tebangan PT AYI yang baru akan semakin meningkat. Dampak terhadap lingkungan lokal yang ditimbulkan oleh penebangan liar biasanya lebih ringan bila dibandingkan dengan dampak penebangan yang dilakukan oleh PT. AYI, karena para petugas illegal itu tidak menggunakan alat- alat berat seperti bulldozer dalam penebangan, sehingga mengurangi kerusakan tanah dan tumbuhan yang ada disekitar areal. Lagipula kayu, kulit kayu dan sisa

- 9. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 viii penggergajian yang tertinggal disekitar areal penebangan kemungkinan berguna bagi pemeliharaan unsur organik tanah. Bagaimanapun, dampak penebangan hutan terhadap prospek peremajaan kondisi hutan secara keseluruhan benar-benar negatif setidaknya berdasarkan tujuh alasan: (1) berkurangnya pohon induk benih komersil, (2) ketinggian hutan berubah menjadi lebih rendah dan lebih terbuka, layaknya hutan sekunder, (3) para penebang liar menjadi ancaman terjadinya kebakaran hutan selama musim kemarau, (4) penebang liar akan membuka ulang jalan-jalan dan lintasan yang seyogyanya ditinggalkan untuk peremajaan, yang dapat mengakibatkan penumpukan sampah dan erosi, (5) para penebang liar menebangi pohon-pohon growong yang tidak layak tebang serta merupakan sarang dan tempat berkembang biaknya margasatwa, (6) para penebang liar menebang semua pohon yang menghasilkan kayu komersial dalam jarak sekurang-kurangnya 1 km kiri- kanan sungai, dan (7) penebangan liar yang berada didekat jalan utama memancing minat orang-orang untuk membuka ladang. Berdasarkan beberapa faktor, pemerintah terkait/berwenang sepertinya enggan untuk “mengambil tindakan represif” untuk menghentikan aksi para penebang liar. Keterlibatan beberapa aspek dalam bisnis kayu illegal menciptakan satu dari sangat sedikit kesempatan untuk dapat menghasilkan uang-dengan melakukan pekerjaan di daerah Tabalong, terutama untuk para remajanya. Bagaimanapun, ada banyak peluang pekerjaan bagi mereka yang terlibat dalam penebangan illegal yang dapat dipadukan ke dalam kegiatan HTI. Pengelolaan hutan lestari (SFM) di dalam areal HPH PT. AYI tidak mungkin berhasil jika jumlah penebangan liar dan pertambahannya selama periode bulan Agustus 1999 sampai dengan Februari 2002 terus berlangsung. Cara terbaik untuk memperbesar kemungkinan pelestarian hutan produksi dalam jangka waktu panjang di Hulu Tabalong, yaitu: - Meminimasi kesempatan para petugas illegal untuk dapat menebangi hutan (misalnya dengan mengatur pengalokasian RKL dan RKT untuk memperkecil meluasnya jalan sekaligus membangun jembatan dan membuatkan gorong-gorong dengan jenis kayu yang cepat membusuk dan roboh setelah ditinggalkan oleh PT AYI); - Memberikan perhatian yang serius dalam mengembangkan penanaman pohon di kawasan yang tidak berhutan (dimulai dengan pemecahan masalah tentang kepastian lahan); dan - Berkonsentrasi dalam usaha untuk memperluas dan meragamkan kesempatan kerja di daerah Tabalong. Tapi semua usaha tersebut tidak akan terasa hasilnya atau sudah terlambat apabila tidak ada tindakan tegas dari aparat pemerintah/badan berwenang terhadap para penebang liar.

- 10. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 ix ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AAC AWP 2 Annual Allowable Cut Annual Work Plan 2 for the period January 1st to December 31st 2001 AYI PT Aya Yayang Indonesia (project forest concession partner) BAPPEDA Badan Perencanaan Daerah (=Local Planning Board, can be provincial or district) BKSDA cm dbh Balai Konservasi Sumber Daya Alam (= Natural Resources Conservation Office) centimeters Diameter at breast height FMU Forest Management Unit HPH Hak Pengusahaan Hutan (= Forest Concession Right) HTI Hutan Tanaman Industri (= Industrial Tree Plantation) IDR Indonesian Rupiah ladang non-irrigated rice farms, usually planted with rubber after one or two harvests m3 cubic metres NTFP OWP 1 Non-Timber Forest Products Overall Work Plan for Phase 1 of SCKPFP PEMDA RTRWK RTRWP Pemerintah Daerah (=Local Government) Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Kabupaten (district land use plan) Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Propinsi (provincial land use plan) RKL Five year logging work plan RKT Annual logging work plan SCKPFP South/Central Kalimantan Production Forest Programme SK Surat Keputusan (= Ministerial Decree) SFM Sustainable Forest Management

- 11. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 x Table of Contents PREFACE i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................................................................................ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................................iii RINGKASAN (Indonesian Summary).................................................................................................................................vi ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS..............................................................................................................................ix 1 AIMS .................................................................................................................................................................1 1.1 General background ...........................................................................................................................................1 1.2 Specific aims......................................................................................................................................................1 2 HISTORICAL AND LEGAL CONTEXT.....................................................................................................2 2.1 Historical background ........................................................................................................................................2 2.2 Current legal aspects ..........................................................................................................................................3 3 METHODS .......................................................................................................................................................4 3.1 Field observations ..............................................................................................................................................4 3.2 Traffic monitoring..............................................................................................................................................4 4 RESULTS & DISCUSSION OF SURVEY RESULTS.................................................................................5 4.1 How trees are selected, felled, sawn and transported.........................................................................................5 4.1.1 Tree selection .....................................................................................................................................................6 4.1.2 Felling and sawing .............................................................................................................................................6 4.1.3 Hauling from felling site to river or road ...........................................................................................................6 4.1.4 Transportation by river.......................................................................................................................................6 4.1.5 Transportation by road .......................................................................................................................................7 4.2 The main timber source areas and flow routes...................................................................................................7 4.3 The people involved...........................................................................................................................................8 4.3.1 Origins................................................................................................................................................................8 4.3.2 Numbers.............................................................................................................................................................8 4.3.3 Experience and attitudes.....................................................................................................................................9 4.4 Limiting factors................................................................................................................................................10 4.5 How much is removed by operators other than PT AYI ? ...............................................................................10 4.5.1 Reliability and completeness of information obtained.....................................................................................10 4.5.2 Estimate of volumes of timber removed ..........................................................................................................11 4.5.3 Estimate of wastage..........................................................................................................................................13 4.5.4 Estimate of commercial volume of timber cut & number of trees ..................................................................14 4.6 Trends ..............................................................................................................................................................14 4.6.1 Non PT AYI logging, July 1999 – March 2002...............................................................................................14 4.6.2 Likely future trends..........................................................................................................................................15 5 ENVIRONMENTAL AND ECOLOGICAL IMPACTS ............................................................................19 6 PROSPECTS FOR CONTROL....................................................................................................................21 7 CONCLUSIONS ............................................................................................................................................22 8 References.......................................................................................................................................................23 List of Tables

- 12. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 xi Table 1 : Traffic Monitoring Locations ....................................................................................................................................4 Table 2 : Characteristics of main timber trees taken by operators other than PT AYI .............................................................5 Table 3 : Summary of results from Monitoring Location A...................................................................................................11 Table 4 : Summary of results from Monitoring Location C ...................................................................................................12

- 13. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 1 1 AIMS 1.1 General background Five sub-activities listed in SCKPFP AWP 2 refer to illegal logging in the PT AYI forest concession area, including 1.9.1 “To review information available on illegal logging activities within (the PT AYI) HPH”, 1.9.2 “To identify the extent that illegal logging impacts upon sustainability of forest management”, 1.9.3 “To develop proposals to reduce impact of illegal logging on SFM”, 4.1.5 “To investigate the wood flow and market for illegal logs from the project concession”, and 6.4.2 “To improve forest protection procedures for forest encroachment, forest fires and illegal operations”. Some of these issues (including the market for illegal logs, forest encroachment and forest fires) are addressed in separate reports. This report addresses only issues related directly to the felling and flow of illegal wood out of the PT AYI area. It does not touch on the “chain” that links tree fellers to the ultimate destination of the wood. 1.2 Specific aims This report aims to : - outline the historical and social background to illegal logging in upper Tabalong; - outline the current legal situation regarding the status of forest land and illegal logging in the PT AYI area; - show the critical points through which most illegal wood is transported; - outline the general process by which timber is felled and removed from the forest by operators other than PT AYI; - provide an estimate of the volume of wood and number of trees removed illegally from the PT AYI area annually during the period July 1999 – March 2002; - provide an assessment of the environmental and ecological impacts of illegal logging on the forest in the upper Tabalong area; and Based on the above, the report then seeks to : - assess the future prospects for SFM in the PT AYI HPH in view of the prevailing extent and impact of illegal logging; and - suggest possible ways forward to address illegal logging in relation to SFM in the PT AYI area.

- 14. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 2 2 HISTORICAL AND LEGAL CONTEXT 2.1 Historical background Presumably most of South Kalimantan was once covered in forest. People inhabited the Gua Babi cave near Muara Uya, upper Tabalong more than 5,000 years ago (Widianto et al., 1997). Seemingly, most of the flatlands and larger alluvial river valleys were converted to farmland hundreds of years ago. Around 1650, it is believed that the Amuntai area was inhabited by Manyan Dayaks, who then emigrated northwards due to pressure from Banjar and Javanese pepper farmers (Hudson, 1972). In the mid 19th century, “all the canoes that are used on the Barito (River) and in the (Banjar) sultanate are made almost exclusively by (Manyan) Dayaks of the Padju Empat (= the area around Telang, through where PT AYI takes logs to the Barito River). … the canoe makers have denuded the whole territory of heavy timber so that .. it is only by renting forest tracts from their neighbours that they are able to continue their profession.” (Dutch administrator’s report, 1857, quoted by Hudson, 1972). Dayak communities in upper Tabalong probably protected specific areas under natural forest for spiritual and practical reasons (e.g. water, useful trees). Dayak people accord ownership rights to farmers and their descendents for land which has been farmed, and to trees which have been planted on that land. Under adat tradition, forest land neither protected by local agreement, nor claimed by other communities, nor previously farmed would generally be regarded as available for felling of trees for wood or for farming. In 1835, the Banjarese Sultan Adam (1825-57) formulated and published the “Undang-undan Sultan Adam” which represents the first codified law for the Banjar community. The law makes no mention of forest land, but three districts are named (Halabiu, Negara and Ulu Sungai, all areas south of upper Tabalong) and it is mentioned that persons who abandon farmed land for more than two seasons without any sign of ownership, such as planting, relinquish rights over that land. Historically, the pattern was of Banjar people moving northwards up major rivers, with Dayaks in turn moving into the upper tributaries. By the nineteenth century in what is now Kabupaten Tabalong, Banjar people had settled along the alluvial terraces of the Tabalong while Dayak people (mainly Lawangan and Deah) were concentrated along the smaller and upper river valleys. The existence of old secondary forest with mature fruit trees even in the upper Tutui River valley (e.g. near Muara Sinangoh; Ecologist field notes, 15 May 1999) shows that there were Dayak settlements here about a century ago. In the 1890’s, there were Dutch tobacco plantations employing local labour at Mahe and Muara Uya, along the Tabalong Kanan valley, while starting from the early 1900’s, rubber planting by European investors and local Banjar planters expanded rapidly until the 1930’s in the Tabalong river valleys (Lindblad, 1988). Until the development of roads to extract wood from the hills north-west of the Tabalong River between Tanjung and Mahe, in the 1960s, most human travel,

- 15. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 3 settlement and trade on the north bank of the Tabalong River would have followed rivers. Banjar settlers moved into the Salikung area of the Ayu River by river around 1958 and Miho (= Mihau) only in 1970 (Yus, 2001). The waterfall and rapids of Riam Tampulingun on the Tabalong Kiwa River just above Miho (Map 1) would have acted as a partial barrier to settlement and trade upstream of this point. The construction of a major logging road by the operators now known as PT. AYI starting in the early 1970’s opened up a large area of predominantly hill forest that had previously been inaccessible to local people as a source of timber for trade. Based on traditional Dayak adat and Banjar customs, any forest land which shows no sign of use or habitation in upper Tabalong would be regarded as open access and the trees regarded as not owned by anyone. Under the Basic Constitution of Indonesia (1945), the Agrarian Law (5/1960), Basic Forestry Law (5/1967) and its replacement (41/1999), forest land and the trees on it are regarded as vested in the state unless the state formally grants rights to individuals, institutions or companies over specific land or forest areas. 2.2 Current legal aspects According to the RTRWK for Tabalong and RTRWP for South Kalimantan, all the land covered by the PT AYI concession is currently designated as forest land. There is no indication that rights to land use or ownership have been granted under the Basic Agrarian Law (5/1960) within the production forest area allocated to PT AYI. Thus, the land within the PT AYI concession is regarded as state forest (hutan negara) as defined in articles 1 and 5 of the Forestry Law (41/1999). According to the RTRW maps, the forest encompassed by the PT AYI concession area represents a combination of production forest, limited production forest and “protection forest” (hutan lindung) or “protection area” (kawasan lindung”). The exact locations and legal status of land referred to as “protected” (lindung) has yet to be resolved. According to the Forestry Law (41/1999), Article 50(3) no one is allowed, without a licence or legal authorisation, to (a) occupy a forest area, … (e) cut trees within a forest area, … (h) carry, possess or keep forest products, … (j) bring heavy equipment used for loading forest products in a forest area, or (item k) bring in equipment used for felling trees. A Ministerial Decree (840/Kpts-II/1999) renews the forest utilisation right of PT. AYI from 6 October 1999 for a period of 55 years within the approximate area shown on Map 1. Together, these three documents (RTRW, Forestry Law and Ministerial Degree) mean that under Indonesian law the land area shown as encompassed by the HPH of PT AYI is a state forest area that has been allocated for harvesting by PT AYI, and that commercial felling and extraction of trees by parties other than PT AYI is illegal.

- 16. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 4 3 METHODS 3.1 Field observations Field observations of Ecologist made during more than 30 separate visits to the PT AYI area over the period April 1999 to March 2002 and information supplied by other SCKPFP team members was reviewed for this report. The field observations include : discussions with PT AYI field staff; discussions with persons met felling and sawing trees in the forest; discussions with persons met hauling sawn timber in the forest and loading it on to trucks; notes on sawn timber and remains of felled trees seen in the forest and on road sides; observations of people loading sawn timber on to trucks within the PT AYI area and the movement of these trucks in the upper Tabalong area; and observations of sawn timber being floated down the Pasuang, Ayu, Bayur (Kumap), Tutui and Missim Rivers. 3.2 Traffic monitoring Based on the general field observations (3.1), it was concluded that the great majority of illegal timber felled within the PT AYI area passes through one of three Locations : Location A the PT AYI timber extraction road between Lalap and Bentot, Location B the lower Tabalong Kiwa River at Mahe, and Location C the road between Binjai (on the Ayu River) and Muara Uya (see Map 1). Monitoring of traffic passing these three Locations, in both directions, was done as shown in Table 1. The purpose was to obtain quantitative information on the flow of people and products in relation to the PT AYI concession area, with the flow of timber an issue of special interest. Continuous monitoring was done at Location A because this was clearly the route through which most illegal timber is removed; monitoring was not done continuously as Locations B and C because local informants stated that the only traffic passing at night time would be unusual and emergency circumstances. At each Location, monitoring was done by a family, from their own house, taking turns on duty through the day. Table 1 : Traffic Monitoring Locations Location What was recorded Monitoring period & times (A) Road between Bunu & Bentot All motorised vehicles & their contents / load 29 October 2001 – 29 January 2002, 24 hours every day (B) Tabalong Kiwa River near Mahe All traffic up & down the Tabalong Kiwa River 1 February – 5 March 2002 inclusive, 05.00 – 19.00 hours daily, but excluding 22 February (C) Road between Binjai & Muara Uya All motorised vehicles & their content / load 30 January – 5 March 2002, 05.00 – 24.00 hours daily

- 17. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 5 4 RESULTS & DISCUSSION OF SURVEY RESULTS 4.1 How trees are selected, felled, sawn and transported Eight main timber tree types were noted to be taken by operators other than PT AYI, and each has different characteristics (Table 3). Table 2 : Characteristics of main timber trees taken by operators other than PT AYI Timber type Tree & wood characteristics Felling & sawing Transportation Meranti (red, yellow & white) (Shorea species) Widespread along river valleys & hills; wood density 300 – 800 kg/m3; multi-purpose, including house walls Trees about 35 cm dbh and above are felled; various sizes sawn, but 30 x 15 x 400 cm most common By river : no floats needed; tied in “rafts” of 15-40 pieces. By road : trucks may be overloaded to 10 – 15 m3 Bangkirai, Angih (Shorea laevis) Mostly on hills; wood density 600 – 1160 kg/m3; favoured for posts, frames, beams, joists Trees above 80 cm dbh favoured; sawn to various sizes Normally by road on trucks; due to high wood density and high value, loads of less than 6 m3 seem normal Keruing (Dipterocarpus species) Mostly on hills; wood density 600 – 980 kg/m3 Trees above 50 cm dbh favoured; various sizes sawn, including small planks Commonly by road on trucks Kapur, Sintok (Dryobalanops laneceolata) Hills & valleys; wood density 600 – 1100 kg/m3; favoured for flooring Trees above 50 cm dbh favoured; various sizes sawn, including small planks Commonly by road on trucks Dungun, Mengkulang (Heritiera species) Scattered on low hills; wood density 520-890 kg/m3; Interior construction, favoured for its rich red colour Various sizes sawn, including small planks Commonly by road on trucks Jelutung, Pantung (Dyera cosulata) Scattered on low hills, but almost extinct from accessible areas; wood density 220-560 kg/m3; specialist interior use Trees above 70 cm dbh favoured; various plank sizes sawn Only records are by truck Jabon, Bunto, Kelempayan (Anthocephalus chinensis) Common in secondary growth along most roads; wood density 290-465 kg/m3; interior use Trees above 35 cm dbh (few exceed 60 cm); this is the only tree removed in the form of round logs, and not sawn in the forest By road on trucks; logs 2 – 4 metres long Ulin (Eusideroxylon zwageri) Lowlands only; threatened due to overharvesting; 880-1190 kg/m3; house posts, window frames & roof shingles All trees big enough to be sawn or split as shingles for sale are now felled (> about 20 cm dbh); various sizes, according to order By river, with Macaranga wood floats; or by road in pickups or tied to sides of four-wheel drive wagons Sources: Ecologist field note based on observations and discussions with tree-fellers. ”Timber type” includes local names in upper Tabalong & scientific names. Wood density figures, at 15% moisture content, from Soerianegara & Lemmens (1994).

- 18. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 6 4.1.1 Tree selection Few tree types appear to be felled other than those listed in Table 2. Exact selection of trees to be felled is based primarily on a combination of the market (prevailing orders by timber buyers, and trends may change; see 4.4) and the relative ease or difficulty of moving the timber to a road or river. Meranti probably represents the most commonly felled type because it is the most common and widespread type. Also, its relatively low density and light weight mean that it can be hauled and floated rather easily and large volumes stacked on to trucks. Bangkirai and ulin fetch the best prices, but their localised occurrence and high density mean that they are more troublesome to saw and transport. Based on the Ecologist’s field notes for years 200-2001, the furthest distance trees are felled from a road or river in a straight line is just over 1 km, perhaps up to 2 km distance on the ground. In selecting a tree for felling, there is an interplay of several criteria, notably (a) type, diameter and quality of trees, (b) distance from road or river, (c) prevailing gradient between site of felling and the road or river, and (d) the dimensions to which the timber is to be sawn into beams or planks. 4.1.2 Felling and sawing All trees are felled and sawn, where they fall in the forest, with chainsaws. No hand sawing was observed. Where timber is to be hauled downwards or along a stream, 30 x 15 (or even 20 or 30) x 400 cm beams can be sawn. In other circumstances, timber is usually cut to smaller dimensions. Two exceptions are jabon (where logs are winched to the road) and ulin (where small planks or shingles are cut in the forest). 4.1.3 Hauling from felling site to river or road Most timber cut by unlicensed operators is hauled from felling site to a road or river by manpower, with one person hauling one piece of timber. Teams of men do not haul logs, and no animal power is used. Pieces of timber are hauled by whichever route is easiest; this includes along old roads and skid trails, down ridges and along small river and stream beds. The sawn timber is stacked on the side of any road that can be reached by a truck. Sometimes, bulldozers appear to be used to skid logs nearer to a road for illegal operators to saw. No bulldozers other than those operated by PT AYI have been seen within the PT AYI area. Most jabon trees (being normally felled within about 30 metres from a road), occasionally other small diameter trees and sometimes sawn planks near roads, are winched to the road by a modified Toyota “Hardtop”. 4.1.4 Transportation by river Sawn timber is tied together to form rafts for transportation by river. Typically, three or four beams or planks are tied side-by-side, and these groups of three/four are then tied in lines of between six to ten. Thus, one raft consists of between about 24 – 40 beams or planks. Light-weight wooden floats, often poles of Macaranga, are tied to dense wood, notably ulin. Ease of transportation by river is highly dependent on water depth. The majority of work is done during rainy periods when water levels are high. Little or no river transportation is done during dry periods.

- 19. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 7 4.1.5 Transportation by road Almost all sawn timber is loaded manually on to trucks for transportation by road. Almost all trucks used are yellow-painted Mitsubishi Colts, with about 95% being 120 horse-power (which can theoretically take a maximum load of about 8 m3) and the balance 135 horse-power (which can theoretically take a maximum load of about 10 m3). Sawn ulin wood and small quantities of planks of other timbers are transported by four-wheel drive pickups. 4.2 The main timber source areas and flow routes The main timber source areas within the PT AYI area can be divided into three Zones, whereby the great majority of that timber then flows through three “bottleneck” Locations A, B and C (as outlined in section 3.2). These three Zones are not 100% clear-cut, but represent a convenient way to picture the main flows of timber out of the concession area, and upper Tabalong in general. Zone A consists of the entire western and central part of the PT AYI concession area up to an imaginary line which is drawn about 1 – 1.5 km west of the course of the Kumap River (Map 1). Timber from this Zone represents all the timber which can be seen in yellow Colt trucks and occasionally small four wheel drive vehicles, passing down the PT AYI road south of Panaan and through monitoring Location A (3.2). More specifically, this timber comes from : a distance of at least 1 km from the sides of all roads that are accessible to trucks during dry weather; current and abandoned but accessible PT AYI felling blocks; and from the Tutui and Missim Rivers. Timber from these two rivers is taken out of the Tabalong Kiwa River and loaded on to trucks at Panaan. In 1999, a small percentage of timber from Zone A was transported out via road over the Kumap River to Mahe (Ecologist field notes, July 1999) but the bridge has collapsed since then. In addition, a small percentage of timber from Zone A is floated down the entire Tabalong Kiwa River, past Panaan and over the Riam Tampulingan waterfall and rapids, thereby coming out at monitoring Location B. However, this is possible only during very high water levels for light weight timber, and involves risks of human safety and loss of timber. A local informant at Panaan stated that a few people prefer this route because sawn timber fetches a 20% higher price at Mahe than at Panaan. Zone B consists forest along the Kumap River (Map 1). Due to the very bad condition of the roads between Kumap village and the Hutan Sembada and Tricorindo since 1999, it is assumed that all or almost all timber from this Zone has been removed via the Kumap and Tabalong Kiwa River, passing through monitoring Location B (3.2). Zone C covers the catchments of the Ayu and Pasuang Rivers. Almost all timber from Zone C passes down the Ayu River and is taken out and loaded on to trucks at Binjai. This timber then passes via monitoring Location C (3.2). A small percentage of timber from Zone C is floated past Binjai and comes out at Pasar Batu (local informants and personal observations; Map 1). Also, small amounts of timber are cut from the hills north-west of Solan (local informant; Map 1), and removed via old tracks in dry weather, but this timber is largely or entirely from outside the PT ATI concession.

- 20. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 8 4.3 The people involved 4.3.1 Origins The majority of people met involved in felling trees, sawing timber, hauling the timber to roadsides or riversides, loading timber on to trucks and floating sawn timber down the rivers of upper Tabalong appear to originate from villages between Tanjung town and Solan, along the Tabalong Kanan River. Their ages appear to range from about 14 years (teenagers typically hauling planks through the forest or meranti beams along streams in the forest) to early 50’s, with an overall majority probably in their late 20s - 30’s. Those operating in Zone A (section 4.2) appear to originate mainly from the villages between Tanjung town and Mahe area, also Jango and Panaan (but the families of Jango and Panaan people themselves originate from the Tanjung – Mahe – Muara Uya area). The origins of those operating in Zone B (section 4.2) are unknown. Those operating in Zone C (section 4.2) appear to originate mainly from the villages around Solan, Muarauya and along the lower Uwi River (incorrectly called Tabalong Kanan on the 1:50,000 topographical maps) between muara Sungai Ayu and Muara Uya (see Map 1). Some of these Tabalong men have travelled and worked widely, notably in HPHs and mining companies in East and Central Kalimantan; one claimed to have worked in Sumatera, another planting rattan in the Sabah Foundation concession in Malaysia. The few exceptions noted were : (a) people from Missim involved in felling ulin wood on the Missim River; (b) a few people from Central Kalimantan and from the east coast of South Kalimantan (all operating in or near the Arboretum); and (c) local people operating north-west of the Ayu – Pasuang River junction on land that is probably their ancestral territory. The only women noted (excluding women involved in making ladangs between km 54 – 62) were on the Pasuang River, presumably to assist in domestic chores for the large logging community there. 4.3.2 Numbers No specific efforts were made in the field to count the number of people involved in unlicensed logging in the PT AYI area, but a rough estimate can be made. Zone A During October – November 1999, estimates suggested to the Ecologist by local observers ranged from 20 – 50 non-PT AYI chainsaws in use within the area between km 54 and km 88 (Map 1). A total of about 100 illegal chainsaws was claimed by a local informant for the entire concession in year 2001. The estimate of 50 within Zone A in 1999 number seems plausible because (a) the informant had detailed field knowledge, (b) during a check in March 2002, there were 28 active illegal operator camps between km 54 and 84 (this excludes camps elsewhere, and presumably there was at least one chainsaw per camp), and (c) if one chainsaw man can cut between 1.5 - 2 m3 of sawn timber per day, this would be equivalent to about 75-100 m3 sawn daily, which is very close to the estimate based on traffic monitoring for the average daily volume of timber removed from Zone A (see section 4.5.2). Each chainsaw man might have an average of two or three helpers to take turns in sawing and to haul timber to the road or river. This yields an estimate of 50 x 3.5 persons = 175 persons involved in felling and sawing within Zone A. If it is assumed that an average of 10 trucks takes timber out of Zone A daily, with a driver and an average of 4 additional persons to load timber on to the truck (the

- 21. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 9 range seems to be about 2 – 8), this represents a further 5 x 10 = 50 persons involved daily. Since timber can be transported at all times from at least parts of Zone A, these estimates can be regarded as daily averages through the year. Zone B There is no information for this Zone, but the numbers are likely to be small (there is much less timber available and it is difficult to transport to a buyer) and variable (according to the level of the Kumap River, now the only means to transport timber from this Zone). Possibly there are a few small groups operating here during rainy periods and no-one operating during dry periods, equivalent to perhaps less than 10 persons per day on average. Zone C During visits to this area (Pasuang River), 29 April–1 May 2000 and 1-3 August 2000, the Ecologist encountered many tens of men and youths involved in felling, sawing and hauling timber to the Pasuang River, and floating it down the Pasuang River. It was estimated at these times that probably over 100 persons were operating there. This estimate cross checks quite well with the estimate of 225 men for Zone A, from where it is estimated that four times the amount of timber is removed per year (4.6.2), but where fewer men would be needed because conditions of terrain and transportation are considerably easier. Less than ten men per day are involved in loading and driving trucks from Binjai (section 4.5.2). Based on the above observations, it is estimated that on any one day, an average of about 285 men and youths are engaged in unlicensed felling, sawing and manual transportation, and an additional. An average of up to 60 men may be involved removing timber by truck from the PT AYI forest area. It must be noted that the above estimates refer to the number of people working in connection with obtaining and removing unlicensed timber within the PT AYI at any one time. One individual may spend anything between a few hours (truck drivers and helpers) to about four weeks in the forest (the maximum a fit man can stand conditions if he does not become sick, and mainly in the upper Tutui and Pasuang River areas, where transportation in and out of the work site is most difficult). All workers take time off to recuperate from exhaustion, poor nutrition and illness. Informants in Zones A and C state that malaria affects many operators and there are reports of deaths from malaria amongst operators, especially in the area around km 81 during year 1999 – 2000. 4.3.3 Experience and attitudes No specific efforts were made in the field to ascertain the experience and attitudes of unlicensed operators, but some general observations can be made. Like any other group of people involved in a particular endeavour, they vary widely in both aspects. Some tree fellers are experienced (albeit largely self-taught) with a wealth of experience, having spent years involved in timber as well as harvesting non timber forest products all over the upper Tabalong forests, and they take a pride in their skills and knowledge. At the other end of the spectrum are those who know little of forest life, have started this line of work only recently, and who fell small and faulty trees left by previous operators not far from a road, leaving much wasted wood and sometimes danger to others. Quite often, the trunks of faulty trees (with hollows or rotten wood) are seen either partly sawn through and abandoned still standing, or felled and then abandoned after the tree has fallen.

- 22. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 10 4.4 Limiting factors There is a smoothly-running system of producing illegal timber and transportation out of the PT AYI concession area. The precise locations of felling and the routes by which timber is removed are quite flexible, with rivers preferred during rainy periods and roads during dry periods. After the preferred large diameter trees are felled, it is possible to return later to take smaller trees. Currently, the only factors locally within upper Tabalong limiting the amounts of trees felled appear to be (a) the number of chainsaws available, (b) the extent of roads accessible to trucks within the PT AYI area and (c) distance from a road or river (normally about 1 km in plan view). 4.5 How much is removed by operators other than PT AYI ? 4.5.1 Reliability and completeness of information obtained There are three main ways in which the estimates provided below (section 4.5.2, and Tables 3 and 4) might be faulty: (a) the observers at the Monitoring Locations might be inaccurate, (b) the monitoring periods might not be representative of one year, and (c) there might be other routes by which timber is removed from the PT AYI area. Regarding observers, it is likely that a small number of records of trucks carrying timber were either missed or wrongly recorded (especially at night, trucks would be recorded as carrying timber based on sound and experience, not necessarily because timber was seen). However, as a percentage of all records, such errors are believed to be very small. Regarding whether data was from representative periods, it is believed to be likely that the periods of data collection were either typical or represented periods when timber flow was slightly lower than average. Monitoring at Location A was over a three-month period in the “rainy season” with 60 out of the 93 monitoring days experiencing at least some rain. On a casual basis between May – October 2001, the Ecologist noted up to 16 trucks on the road between km 63 and Bentot within a 2 hour period, suggesting that the rate of timber removal from Zone A may have been greater earlier in 2001. The information for Zone C covers periods of relatively low river levels, when volumes of timber removed will be relatively low. Regarding other routes out of the PT AYI area, no investigation was done to ascertain if timber is removed from the Bianon – Awang area to the west of the concession. In mid 2001, an abandoned road linking Bahalang (= Amparibura) to Ampah via Siong was re-opened. Due to the long distance involved and the poor quality of this road, it is assumed that no timber is removed from the PT AYI area via this route. Overall, it is believed that the information sources used in this report are adequately reliable and complete to provide estimates, but that the available information may slightly underestimate the annual volume of timber removed during the period 1999-2002.

- 23. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 11 4.5.2 Estimate of volumes of timber removed Zone A Based on the results from Monitoring Location A, an average of 10.2 truck loads of timber/day (including jabon logs) and an average of 1.2 pickups/Hardtops with timber or planks/day were recorded coming from Zone A. Daily average removal of sawn timber increased from November to January. The lowest number of trucks recorded with timber during one day was 2 trucks (21 December) while the highest number in one day was 20 trucks (8 December). Although days of heavy rain affect traffic, overall timber flow did not appear to vary much according to weather. The apparent trend of increased timber flow over the monitoring period may be due in part to higher water levels in the Tabalong Kiwa River during December – January. Table 3 : Summary of results from Monitoring Location A Description Nov Dec Jan Truck, sawn timber 299 319 297 Truck, jabon logs 18 6 5 Truck other logs 2 0 1 Truck, sawn ulin 0 0 1 Truck, rattan 1 0 0 Truck, damar 0 3 0 Daily average number of trucks with sawn timber & jabon logs 9.8 10.2 10.7 Pickup, sawn timber / planks 18 41 46 Pickup, planks & damar 1 0 0 Pickup, ulin 4 0 0 Daily average number of pickups with sawn timber / planks 0.7 1.3 1.6 PT AYI logging lorry with logs 10 0 25 Number of days with rain 21 20 19 Notes: Table shows only traffic coming out of the upper Tabalong area (north to south). “truck” = trucks not owned by PT AYI.. Nov = number of records between 10.00 hours, 29 October – 24.00 hours, 29 November (32.5 days). Dec = number of records between 00.00 hours, 30 November – 24.00 hours, 31 December (32 days). Jan = number of records between 00.00 hours, 1 January – 10.00 hours, 29 January (28.5 days). “Pickup” includes a few records of Toyota Highlines. This monitoring recorded number of vehicles with timber passing out of Zone A; it was not able to record volume of timber in the vehicles. It is assumed that an average truck contained 8 m3 of timber, based on the following reasons : (a) 8 m3 is reckoned to be the normal maximum load for a 120 horse power truck, and timber traders would normally want to maximise the volume of timber per trip; (b) the normal maximum load for 135 horse power trucks is reckoned at 10 m3, but few such trucks seen in Zone A (perhaps about 5%) are this capacity; (c) some loads will be less than the theoretical maximum, either because timber available at the roadside pick-up point is less, or because the truck driver is unwilling to risk a large load due to poor road conditions off the main road; (d) some loads are more

- 24. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 12 than the theoretical maximum (when sawn timber can be seen loaded above the top of the truck sides, which occurs with perhaps 1 in 10 loads, the load is greater than 12 m3). It is assumed that an average pickup/Hardtop carried 0.5 m3. Thus, the estimate for timber removed from Zone A is 10.2 x 8 = 81.6 m3 per day (in trucks), plus 1.2 x 0.5 = 0.6 (in pickups), which (assuming 30.4 days per month) represents 2,500 m3 per month. Zone B No timber was recorded passing down the Tabalong Kiwa River at Monitoring Location B during the period 1 February – 5 March 2002. Although there is little doubt that volumes of timber coming from this Zone are relatively small, transportation is highly dependent on high water levels in the Kumap River, which means that activity is very seasonal and unpredictable. Thirteen days with rain were recorded out of the 32 monitoring days. In the absence of data for one whole year, a best guess is that an average of only one team operates per day in Zone B, producing 2 m3/day or 60 m3/month. Zone C During two visits up the Ayu – Pasuang River in year 2000, estimates were made by the Ecologist of the daily volumes of timber being removed from Zone C. This was done by counting the number of sawn beams (most 400 x 30 x 15 cm) actively being transported on the river below Muara Pasuang (Map 1). Amounts of sawn timber seen in the river and on land, not in the process of being transported, was very much greater, but was not included in the calculation. The fact that it normally takes 2 days to float timber from the forest site to Binjai, and 3 days to Pasar Baru (according to local informants), was noted in the calculation. The following timber volumes in process of being transported downstream were estimated : 29 March, 34.5 m3; 1 April, 6.5 m3; 1 August, 16.4 m3; 3 August , 16.0 m3. River level was moderately low in March-April and very low in August. These figures indicate a daily average of 18.35 m3/day removed, or 550 m3/month in year 2000. Based on the results from Monitoring Location C, and making assumptions on timber loads per truck (Table 4), an average of 10.6 m3/day is estimated to have left Zone C from end January – early March 2002. Thus, the estimate for timber removed from Zone C in early 2002 is 10.6 x 30.4 (days per month) = 320 m3 per month. Timber flow out of Zone C tends to occur in alternate periods of intense activity (high water levels in Ayu River) and little or no activity (low water levels), each period of unpredictable timing and length. Water level was low during most of the monitoring period, increasing only at end of February – early March during a rainy period Two significant points can be made regarding data from Zone C. Firstly, water levels were relatively low during all three periods with records, so the estimates probably represents an amount less than the average for a whole year. Table 4 : Summary of results from Monitoring Location C

- 25. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 13 Description W 1 W 2 W 3 W 4 W 5 Total µ/day M3/day Truck, sawn timber, full 6 0 1 6 11 24 0.71 8.5 Truck, round logs 0 0 2 0 0 2 0.06 0.5 Truck, load uncertain 2 12 6 3 4 27 0.8 1.6 Truck, empty 7 4 4 5 7 27 0.8 0 Notes: Table shows only traffic coming from Binjai towards Muarauya. Records are for 05.00 – 24.00 hours, (but only to 18.00 hours on final day). W 1 = number of trucks recorded during the week of 31 Jan – 6 Feb; W 2 = 7 – 13 Feb; W 3 = 14 – 20 Feb; W 4 = 21- 27 Feb; W 5 = 28 Feb – 5 March (5.7 days only). Total = total trucks for monitoring period (trucks carrying rubber are excluded). µ/day = average number of trucks per day. PT AYI is not taking any timber from this area. M3/day = estimated average volume of timber removed per day, assuming : trucks full of sawn timber are overloaded and carry 12 m3 per load; trucks with round logs contain 8 m3; of trucks with uncertain load, half carry sawn timber, with 4 m3 per load. Secondly, the early 2002 estimate (at 320 m3/month) is about 40% lower than the year 2000 estimate (at 550 m3/month). Part of the difference may be due to the fact that the year 2000 records cover all timber, whereas the year 2002 records miss the small amounts of timber taken to Pasar Batu. Given the intense activity seen in year 2000, however, it is expected that all accessible large commercial trees have been felled along the upper Ayu and Pasuang Rivers, and that smaller trees, further from the river, now have to be sought by illegal operators. It is assumed that overall during the period mid 1999 to early 2002, an average of 500 m3/month were removed from Zone C, but that future volumes will be much smaller. Overall, based on the information and calculations for all three Zones, it is estimated that an average of 2,500 m3 + 60 m3 + 500 m3 = at least 3,000 m3 is removed per month from the PT AYI concession, equivalent to a minimum of 36,000 m3 per year. 4.5.3 Estimate of wastage There is always wastage of potentially usable wood when trees are felled and transported. The amount of potentially usable wood wasted by illegal operators is high, for the following reasons : (a) entire trees which fall down steep slopes, where sawing and removal of planks is either difficult, very tiring or impossible, are abandoned; (b) entire trees which topple but are trapped by lianas and other tree crowns before falling to the ground are abandoned; (c) trees found after felling to have significant hollows, holes or faults are either abandoned or only partly sawn; (d) most trees are sawn in the forest, and the process of converting a cylindrical shape to rectangles cause inevitable loss; (e) use of a chainsaw produces more waste than use of a peeler or factory saw; (f) due to the presence of seemingly abundant “free” trees elsewhere, many illegal chainsaw operators are extravagant and do not even aim to maximise the amount of wood they saw from any given tree (e.g. any pieces of tree trunk less than 4 m long are typically abandoned). The % of potentially usable wood from any given tree which is left in the forest by illegal operators is highly variable. In the absence of a special study, in the opinion of the Ecologist it is safe to say that 50% of the trunks of trees, which could be

- 26. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 14 extracted by legal operators with skidders and sold to mills, are left in the forest by illegal operators. 4.5.4 Estimate of commercial volume of timber cut & number of trees If the above assumptions are made (4.5.3), then the actual volume of commercially marketable timber cut by illegal operators is double the volume removed and sold. Thus, it is estimated that “annual cut” from the PT AYI concession done by illegal operators is at least 72,000 m3. The volume of timber in the trunks of trees selected by illegal operators is highly variable, varying with species, distance from a road, and relative local abundance of marketable species. Mature meranti and bankirai favoured in 1999 may represent 20 m3 of timber per tree, while a typical jabon may be less than 2 m3. It is assumed that an average tree felled during the period 1999-2002 represents 7 m3 of timber (a 70 cm dbh meranti with a trunk length of 18m). Based on this assumption, at least 10,000 trees were felled illegally each year in the PT AYI area during the period 1999 – 2002. 4.6 Trends 4.6.1 Non PT AYI logging, July 1999 – March 2002 Five trends can be inferred for the period mid 1999 – early 2002. Firstly, amounts of ulin appear to have declined significantly, and by mid 2001, hardly freshly sawn ulin wood was seen in upper Tabalong, suggesting that most accessible mature trees have now been felled. Secondly, jabon was never seen felled prior to early July 2000 (either by PT AYI or illegal operators), after which is became a favoured species. Since mature jabon occurs only along old roads, its supply is now periodic and correlated with the re- opening up of old roads by PT AYI. Thirdly, prior to about August 1999, most illegal felling appeared to be along rivers and in areas away from the main road. Starting around October 1999, the emphasis shifted to felling along the main roads and in newly-opened areas within PT AYI blocks, with illegal operators rushing to fell and claim “ownership” of trees before PT AYI started felling. Fourthly, volumes of timber coming from the Ayu-Pasuang River forests (Zone C) have probably declined, reflecting loss of all large trees from accessible parts of this area. Fifthly, the trend in general was towards taking smaller trees, as all large trees have been felled in accessible areas other than newly-opened PT AYI felling blocks. In 1999 (apart from ulin), almost all trees felled were large (typically above 80 cm dbh) and meranti and bangkirai seemed favoured. Bankirai more than 90 cm dbh were particularly sought in 1999. Keruing, kapur and dungun seemed to become more commonly cut in 2000-2001. In Zone C in year 2000, all trees other than ulin seen felled along the Pasuang River (mainly meranti, kapur and keruing) were above 70 cm dbh. Remaining accessible large jelutung in Zone A were all cut in

- 27. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 15 year 2000. Based on the Ecologist field notes, 2001 was the first year when meranti trees less than 50 cm dbh were seen felled. 4.6.2 Likely future trends In the absence of law enforcement measures, it is predicted that illegal felling will continue and become progressively more damaging to prospects for forest recovery, for the following reasons : - as large accessible trees disappear, size of trees felled will become smaller; - tree species other than those listed in Table 2 will be felled; - as all commercial trees along main roads and larger rivers disappear, illegal operators will continue to maximise efforts in forthcoming PT AYI blocks; - PT AYI machinery may be used more for skidding illegal logs from sites that are currently too difficult for manpower alone; - illegal operators may introduce buffalo, tractors and their own bulldozers into the PT AYI area; - the market for sawn timber and small diameter trees in Tabalong area is unlikely to decline; and - not only harvesting and transportation of timber but also sawing and trading timber in local mills will continue to provide income for many local families.

- 28. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 16 Figure 1. Meranti merah, about 38 cm dbh, felled in the PT. AYI Arboretum, September 2001. Note wood wastage, and removal of last potential meranti seed tree from this locality. Figure 3. Remains of keruing trees felled in August 2001 and sawn at the edge of the main stream in the PT AYI Arboretum. Figure 2. Location of mature trees felled east of the road at km 59, PT. AYI area. Some trees exceeding 80 cm dbh felled in late 1999 have been abandoned. Figure 4. Site of tree felling and sawing east of km 59, about two years after being abandoned.

- 29. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 17 Figure 5. A youth dragging meranti beams (400 x 30 x 15 cm) down the Bayur tributary of Kumap River, July 1999 Figure 6. Floating ulin wood planks down the Tutui River, with Macaranga poles as floats, June 1999. This raft contains 4 x 16 planks.

- 30. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 18 Figure 7. Meranti beams ready for loading on to a truck, roadside, km 75 PT. AYI area. Figure 8. The bridge at Panaan where most timber transported down the Tutui – Tabalong Kiwa River is removed from the river (bottom left) and loaded on to trucks.

- 31. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 19 5 ENVIRONMENTAL AND ECOLOGICAL IMPACTS Many observations were made by the Ecologist of conditions surrounding the sites of trees felled by illegal operators in all the sorts of situations in the PT AYI concession area. From these observations, it is clear that the environmental and ecological impacts of illegal logging in upper Tabalong are : - both direct and indirect; and - locally vary in significance from site to site; but are - highly significant in view of the large number of trees involved (about 10,000 per year; 4.6.4) The immediate local environmental impacts are normally much less severe with illegal logging than with logging by PT AYI. This is largely because bulldozers are normally not used to skid illegal timber, so there is none of the soil compaction, soil pushing and collateral damage to other trees associated with bulldozers. Also, sawn timber hauled by illegal operators, being much smaller per piece than the whole trunks skidded by bulldozers, results in less damage done by the timber to soil and adjacent vegetation. In addition, the large amounts of wood, bark and sawdust left around felling sites is probably beneficial ecologically in maintenance of soil organic matter. However, the impact of illegal logging on prospects for forest recovery overall is severely negative for the following reasons : 1. In general, the fact that illegal operators now take trees as small as 35 cm dbh, and presumably will continue to do so if not stopped, means that the number of commercial seed source trees continues to be reduced. The number of dipterocarp seedlings and saplings is low in many parts of the PT AYI area (probably in part due to high mortality during dry periods, especially the 1997- 98 drought); continuing removal of potential seed trees will tend to result in impoverishment of dipterocarps over much of the area. 2. Similarly to point 1, the continuing removal of ever smaller trees will lead to development of a very different forest quality, with lower stature, more pioneer growth and a dry, well-lit micro-climate unsuitable for organisms sensitive to desiccation and heat. 3. Illegal operators represent worrying sources of fire during dry periods, scattered through the concession, as most smoke cigarettes and all have camp fires using wood for cooking, and they operate in close proximity to dry wood waste. 4. Illegal operators re-open roads, skid trails and areas that should be left to regenerate (old logging roads and felling blocks that were operated by PT AYI during the previous few years), thereby re-exposing soil to erosion and introducing garbage.

- 32. Amounts, impacts & implications of illegal timber removal from the PT AYI forest concession, 1999-2002- Report No. 103-March 2002 20 5. Illegal operators fell defective trees with holes and hollows that represent nesting and breeding sites for some wildlife such as hornbills. 6. lllegal operators have already felled, and will continue to fell if not stopped, all trees yielding commercial timber within a distance of at least 1 km of all larger rivers within the PT AYI area. By law, all forest within 100 m of a river lies within protection areas. The impact of logging here will be to remove substrates for orchid species confined to moist riverine forest (Nasution, 2001) and reduce water quality and food input for aquatic life (Tjakrawidjaja & Pramudyagarini, 2002). Fortunately, many trees near to river banks are either non-commercial species or have very poor form. In terms of timber production, the concern is more within the area 100 – 1,000 m from the river, which due to soil fertility and moisture tends to have good regeneration potential for meranti merah, as long as seed trees are retained. 7. Illegal logging within about 500 m of major roads may act as an incentive for people to make ladangs, because it is apparent to local residents that neither government nor PT AYI are able or willing to protect that forest or land. For these reasons, the net overall environmental and ecological impacts of illegal logging are reckoned to be somewhat negative for soil and water quality, and highly negative to forest recovery, future timber production capacity, and to conservation of rare and sensitive species.