- The document discusses the history of Vyborg, Russia from its founding in the 13th century through World War II. It focuses on how the city changed hands between Sweden, Finland, and Russia over the centuries and was significantly damaged in WWII.

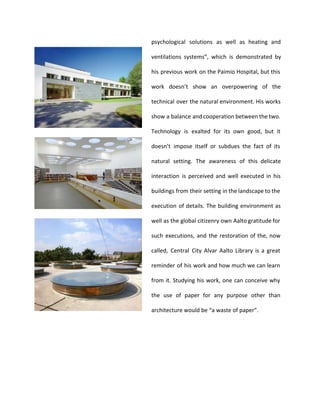

- It then describes Alvar Aalto's design for the Central City Library in Vyborg from 1927-1935, including the use of circular skylights, radiant heating, and various wood types.

- By WWII, Vyborg was a major city in Finland but was heavily bombed during the Winter War and ceded to Russia, with the library now located in Russia.