Quick Reference Guide – The BasicsDr. Susan CathcartGeneral In.docx

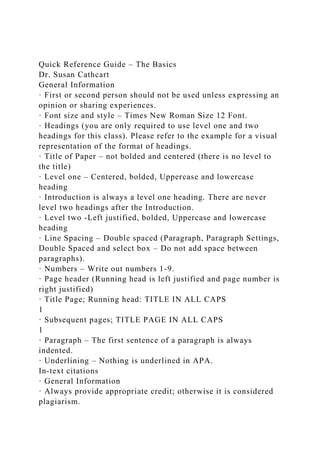

- 1. Quick Reference Guide – The Basics Dr. Susan Cathcart General Information · First or second person should not be used unless expressing an opinion or sharing experiences. · Font size and style – Times New Roman Size 12 Font. · Headings (you are only required to use level one and two headings for this class). Please refer to the example for a visual representation of the format of headings. · Title of Paper – not bolded and centered (there is no level to the title) · Level one – Centered, bolded, Uppercase and lowercase heading · Introduction is always a level one heading. There are never level two headings after the Introduction. · Level two -Left justified, bolded, Uppercase and lowercase heading · Line Spacing – Double spaced (Paragraph, Paragraph Settings, Double Spaced and select box – Do not add space between paragraphs). · Numbers – Write out numbers 1-9. · Page header (Running head is left justified and page number is right justified) · Title Page; Running head: TITLE IN ALL CAPS 1 · Subsequent pages; TITLE PAGE IN ALL CAPS 1 · Paragraph – The first sentence of a paragraph is always indented. · Underlining – Nothing is underlined in APA. In-text citations · General Information · Always provide appropriate credit; otherwise it is considered plagiarism.

- 2. · Everything cited in text must appear on the Reference page. Everything on the Reference page must be cited within the text. · When citing at the end of a sentence, the punctuation should be place after the citation and never before. · When citing in ( ), use & between two or more authors (not the word and). · If there is no year in a Reference, cite as n.d. · If there is no page number, cite as n.p. · When citing at the end of a sentence, punctuation only goes after the citation. · The first time you cite a reference in a paragraph, you must cite the year. · Examples of citations when paraphrasing (you must cite the year the first time you cite a reference in a paragraph). · According to Cathcart (2019), it is always snowy in Michigan. · It is always snowy in Michigan (Cathcart & Ryan, 2019). · According to Cathcart, Ryan, & Masica (2019), you cite three or more authors the first time. · In subsequent citations for three or more authors, you use et al. (Cathcart et al., 2019). · Flowers do not bloom until it is spring (“Today’s gardener,” 2018) or (Today’s gardener, 2018). There is no author listed in this example. · Direct Quotes – Should be avoided as much as possible as this does not provide analysis. If you do not cite with a page number, you will not receive credit. · According to Cathcart (2019, p. 15), “Driving is horrible during an ice storm.” · “Driving is always horrible during and ice storm” (Cathcart, n.d., n.p.). You never use a page number unless you are citing a direct quote. Reference Page – This is a level one heading. This is not an all- inclusive list. · General Information · References are always listed in alphabetical order.

- 3. · The author’s first name should not be used. Only the first letter of the first name is used. · Professional credentials should not be used. · Use & between two or more references (not the word and). · The first letter of the first word and the first letter of proper nouns are capitalized for articles and books. The journal name and the journal number are italicized. Books: Cathcart, S. D. (2015). Communication in the workplace. Cambridge, NJ: Boston Books. Communication in the workplace. (2015). Cambridge, NJ: Boston Books. Journal Articles: Cathcart, S. D. (2019, January 7). Human resource management in Fortune 500 organizations. HR Today, 9(2), 15-22. Retrieved from https://........ Cathcart, S. D., & Ryan, J. (2019). Human resource management in Fortune 500 organizations. HR Today, 9(2), 15-22. Retrieved from https://........ Newspapers: Cathcart, S. D., Ryan, J., & Masica, A. J. (2018, December 30). Roads in Michigan. The Oakland Press, pp. A1. Online Video from the Internet: Cathcart, S. (2019, June 1). How to grow herbs [Video}. Retrieved from http://youtube.com.... Website Articles (remember to avoid .com websites): DOL appeals association health care plan ruling. (2019, May 1). Retrieved from https:// shrm.org *The authority on APA style is the APA manual. FINAL PAPER PROJECT ART AND ARCHITECTURE OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC WORLD 2020

- 4. DUE SUNDAY MAY 3 1. choose an object/structure from the Art&Christianity Ecclesiart Projects site - https://www.artandchristianity.org/ecclesiart-projects OR from slide file posted on Blackboard. 2. Review your slides and notes for an object/structure that you would like to explore, and to compare to a similar although modern one, selected from the sources above. 3. The premise is that you will find significant similarities, as well as differences between the selected image, one that has been created in the 20th/21st centuries, and an object covered in the course, from the 4th to the 17th century. 4. While this project is based on the standard art history compare/contrast exercise, you must also be thinking about the underlying belief, its imagery, its rituals, its adherents, and the impact or the use that EACH of your two objects has on those who experience the object or space in person. 5. Since we are dealing with a very different set of circumstances, my requirements are simple: Images of both objects, and of any other objects that may come into your discussion. A solid bibliography that demonstrates your exploration of both topics. By this I mean VETTED sources including online resources. No popular sites like PBS, for example, although there may be suggestions for further reading connected to some of their programs. The same for Wikipedia – there can be decent bibliographies but be careful. A very good place is of course, the Metropolitan Museum’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art for

- 5. contextual essays, as well as object information. I am finicky about notes, I want them at the end of the paper, not on the page. This is easy to set up in any word processing program. Be careful of plagiarism – any idea as well as direct quotes MUST be cited in your end notes as well as the source included in the bibliography. I am less finicky about the style of format, although I prefer Chicago, just pick one and be consistent. Any questions about format can be found at the Purdue OnLine Writing Lab - https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/purdue_owl.html Length is always arbitrary, right? But for a decent job, the paper should be a minimum of 1500 to 2000 words, but not more than 4000 words - exclusive of bibliography and end notes. Do something of which you are proud; think of this as the culmination of what you have learned in this course. Running head: TITLE OF PAPER – ALL CAPS 1 TITLE OF THE PAPER 3 Comment by Dr. Susan Cathcart: Please notice that the h in Head is not capitalized.

- 6. Title of Paper Your Name Comment by scathc01: Don’t’ forget to include your name here! Don’t forget to remove any comments. Columbia Southern University You are required to use headings for all assignments for this class. Title of Paper Introduction Comment by Dr. Susan Cathcart: You must include an Introduction for all assignments. The Introduction includes 4-6 sentences overview of the topic and 3-6 sentences overview of the paper. The overview of the paper tells me what I am going to read in the next 3 or more pages. The heading following an Introduction is always level one. This is your introduction where you have a comprehensive overview of the topic. Then you need an overview of the paper. The next heading is always level one. Level One Heading Comment by Dr. Susan Cathcart: Never use Part I or Part II as headings. Headings tell the reader what to expect next.

- 7. The heading after an introduction is always a level ne heading (centered and bolded). Text starts here. You must always have paragraph after a heading. Level Two Heading Text starts here. The level two heading is a sub-heading of a level one heading. Leadership Styles Comment by Dr. Susan Cathcart: Don’t forget to cite when you paraphrase. Essentially, you will have a citation in every paragraph. If you do not cite, you will not get credit for what you write. Direct quotes are not analysis without a substantial discussion of relevance. If you feel you must use a direct quotes, you must cite with author, year, p. #. If you do not include a page number, no credit is earned for the quote. Paragraph starts here. Servant Leadership Paragraph starts here. Transformational Leadership Paragraph starts here. Conclusion The conclusion should include 4-5 sentences providing a summary of the facts/findings for the assignment. This is the end to the paper. There are no headings after the Conclusion. **This template provides examples of headings that are 2-5 words long. The organization and the words used in a heading are up to you. You never ask a question in a heading nor use Part I or Part II as headings. References Comment by Dr. Susan Cathcart: Always in alphabetical order. The reference and citation must match.

- 8. Author, A. A., & Author, B. B. (Year). Title of the journal article is case sensitive. Name of the Journal in Title Case, vol(issue), starting page-ending page. Retrieved from… Author, A. A. (Year, Month Date). Title of the newspaper article is case sensitive. Name of the Newspaper in Title Case, vol(issue number), page-page. Retrieved from name of the database. Author, A. A. or Organization Name, if available. (Date of publication; use n.d. if there is no date). Website document title – case sensitive. Retrieved from URL. Author, A.A. (2019). Title of the book is case sensitive and italicized (3rd ed). City, State: Publisher. Other hints: 1. The expectations do not provide the headings nor the organization. This is up to you to determine. Headings – not formatted as a question. Headings tell me what to expect in the next discussion. You do not Part I or Part II as a heading. 2. Everything is formatted in Times new roman size 12 font. 3. Everything is double spaced. To do this, you select Don’t add space in the paragraph settings. 4. You must cite in every paragraph unless solely based on your experiences. If you do not cite, you will not receive credit. 5. Direct quotes – should be avoided and when used, you must explain its relevance in 3-4 sentences. I would prefer if you avoid direct quotes as they are not analysis when you use the author’s own words. a. If you do not include a citation with a page number, you do not earn credit. b. If you do not have a page number when you cite a direct quote, you would use n.p. (Cathcart, 2017, n.p.). c. You do not use a page number unless citing a direct quote. d. If you do not have a year when you cite, you would cite as n.d. (Cathcart, n.d.). 6. When citing three or more authors, cite all authors in the first citation. In subsequent citations, use only the last name of the first author followed by et al. Example - (Cathcart et al., 2018).

- 9. 7. Everything cited in text must appear on the Reference page; likewise, everything cited on the Reference page must appear within text. If this does not happen, points will be deducted. 20 / Regulation / spring 2014 L a b o r I n the United states today, less than 10 percent of pri- vate sector employment is unionized. After peaking at 35 percent in the early 1950s, union membership has been in decline for the last 59 years. The decline represents one of the most important institutional shifts in the U.s. economy. reflecting the decline, a common theme among academic legal commentators is that the law governing unionization and collective bargaining, the national Labor relations Act (nLrA), has been a terrible failure. i believe the opposite is true: the nLrA has been largely successful and in one key area it has been exceedingly successful. Moreover, its presumed failure—declining union enrollment—is due largely to its overall success. in this article, i will describe this success. i will first outline the goals of the Wagner Act (the nLrA’s progenitor legislation), and then explain how the nLrA achieved those goals. i will conclude by explaining why it’s not surprising that those successes would result in declining union membership.

- 10. GOALS OF THE NLRA The first of the Wagner Act goals was, and is, industrial peace. The preamble of the Act states that the “denial by some employ- ers of the right of employees to organize” and bargain collectively M icH A EL L . WAcH T ER is the William B. and Mary Barb Johnson Professor of Law and Economics and co-director of the institute for Law and Economics at the Univer- sity of Pennsylvania Law School. The author thanks Sarah Edelson for research assistance and useful comments for this article. This article is condensed from a chapter in the Research Handbook on the Economics of Labor and Employment Law, cynthia L. Estlund and Michael L. Wachter eds., Edward Elgar Publishing, 2013. had led “to strikes and other forms of industrial strife or unrest.” On one level, that goal means reducing the number of strikes or the economic effects of strikes. But that barely scratches the surface of that goal. industrial strife in the late 19th and early 20th centuries went far deeper, raising the question of whether the employees would agree to work within a capitalist system. prior to 1932, there was no federal legal right to strike, even peace- fully, and many strikes were illegal under state law or the federal com- mon law. Employers often required that workers agree not to

- 11. join a union or be involved in union activities during the term of their employment, and the federal courts held such agreements binding. Concerted activity by employees was not protected. if workers went out on strike and did not return to work when served with a state court–ordered injunction, the striking workers were in contempt of court. When confronted by police or pinkerton guards, strikes would often turn violent. The next move in many strikes was for the governor to call out the national guard to restore order. in the great railroad strike of 1877, federal troops were deployed in major cities in six states, including Baltimore, pitts- burgh, Chicago, and st. Louis. striking workers often resisted, resulting in considerable violence and many deaths. Certainly one could understand president rutherford Hayes’ concern that a revolution against the government itself might be in the mak- ing. Hence, when i use the term “industrial peace” to describe what Congress was seeking, my focus is—and Congress’s focus was—on the unrest that led to riots and the eventual use of police or military force to restore order. Equality of bargaining power / The second goal was, and is, to redress “inequality of bargaining power.” in the words of the Act, The STriking SucceSS of The naTional labor relaTionS acT

- 12. The NLRA has brought labor peace and improved workers’ negotiating power, which may explain why union membership is declining. ✒ By MicHAEL L. WAcHTER B e t t m a n n /C O R B IS wage and the nonunion wage for workers doing similar work. Collective bargaining and higher wages were linked. it was always understood that the collectively bargained wage would be higher than the wage achieved in the nonunion sector. Under the traditional industrial relations view, the procedural goal is achieved when workers join unions and engage in collective

- 13. bargaining and the substantive goal is achieved when the collec- tively bargained wage is set above otherwise-prevailing wages in an unorganized labor market. But that understanding of the second goal of the Act is problematic because it is internally inconsistent, based on flawed and outdated theories of wage determination and of business cycles. The labor market analysis at the time of the great Depression was still rooted in the theories of Thomas Malthus and John r. Commons. Malthus claimed that population growth would always leave a pool of unemployed workers that would keep wages at the subsistence level. Commons, one of the original giants of industrial relations, extended the claim, saying that “cutthroat competition” among workers set the market wage at the wage that the “cheapest laborer” would be willing to accept. To remedy the problem, unions were needed to address the inequality of bargaining power. “[t]he inequality of bargaining power … substantially burdens and affects the flow of commerce, and tends to aggravate recurrent business depressions, by depressing wage rates and the purchasing power of wage earners in industry and by preventing the stabiliza- tion of competitive wage rates and working conditions within and between industries.” Whereas the goal of industrial peace is easily stated, the same is not true of the equality of bargaining power. The second goal is complex because it has both procedural and

- 14. substantive elements. On the procedural element, the legislation’s author, sen. robert F. Wagner (D-n.Y.), said that the goal was satisfied if workers were represented by unions. i will adopt sena- tor Wagner’s interpretation by equating the procedural element with workers’ achievement of collective bargaining status. This provides a clear and measurable goal. The greater the percent- age of workers belonging to unions and engaging in collective bargaining, the more successful is the Act. Hereafter, i use the economic term “union density,” which means the percentage of workers who belong to unions. The substantive element is raising wages, which it was hoped would reduce the likelihood or severity of depressions. The tradi- tional indicator of whether unions raise wages is the union wage premium—that is, the percentage difference between the union spring 2014 / Regulation / 21 B e t t m a n n /C O R

- 15. B IS 22 / Regulation / spring 2014 L a B O R The modern concept of competitive labor markets was unde- veloped at this time. it was not until 1932 that John Hicks pub- lished The Theory of Wages and laid the framework for the neoclas- sical theory of wage determination, and it was several decades later before it became widely known and accepted. in the modern theory of wage determination, the competitive wage is the wage that equates supply and demand. Both employers and employees are “price takers”—neither exercises bargaining power. The com- petitive wage may be a depressed wage in terms of some norm of acceptable living conditions, but it is the market outcome. But the conventional wisdom among policymakers when labor law was being developed in the 1930s was that of Commons and not Hicks. The business cycle language of the Act also creates problems in light of modern neoclassical economic theory. The statutory language looks to unions to raise wages to counter an ongoing deflationary cycle where declining wages result in under- consump- tion and increased unemployment. The under-consumption story was a neat one but there was never any solid economic support

- 16. for it, and it was gradually being replaced by Keynesian econom- ics even as the Act was passed. Keynesian economics posits that a combination of countercyclical fiscal and monetary policy could reduce the severity and length of downturns in business activity. Elevating peace / Two alternative stories can be told in evaluating the two goals. The first story is the one told by the framers of the Wagner Act. industrial peace is an important, clear, and coherent goal of the Wagner Act. replacing industrial strife and unrest with industrial peace makes both employers and employees bet- ter off and has enormous benefits for social welfare. On the other hand, a violent regime of illegal strikes, riots, and the recurring exercise of police power represents a failed industrial relations system. in this story, the goal of equalization of bargaining power seems to fit neatly with the goal of industrial peace. Equality of bargaining power was required for labor disputes to be resolved peacefully. The two goals are thus complementary. The second story reaches a very different conclusion. As a threshold economic issue, the procedural and substantive aspects of the goal of equalizing bargaining power are inconsistent. The higher the union wage, the lower the level of employment in the union sector. Thus the substantive goal of a high wage pulls in one direction, while the procedural goal of more workers covered by collective bargaining pulls in the other. There also is a potential inconsistency between the substantive goal of higher union

- 17. wages and the goal of industrial peace. High union wage, relative to the nonunion wage, means greater management opposition to union demands (and to union organizing efforts generally), thus the greater likelihood of strikes. The complexities and potential inconsistencies inherent in this second goal of the nLrA are one reason for emphasizing the more straightforward goal of industrial peace. But another reason lies in the dramatic statutory revisions of 1947. in the Taft-Hartley Amendments to the nLrA, making greater progress in achiev- ing industrial peace was the paramount goal. At the same time, certain tactics and conduct during labor disputes were restricted, even at the obvious cost of curbing unions’ bargaining power. With the Taft-Hartley amendments, the goal of industrial peace clearly became paramount. THE FOUR LEGAL REGiMES To evaluate the success of the nLrA, i will treat it as one of four alternative legal regimes that have each existed in the United states at some time since the beginning of the new Deal. i will then ask which of the four is most likely to achieve the two goals. in terms of terminology, i note that the nLrA has been amended several times since the original Act—the Wagner Act—was first passed in 1935. When i use the term “nLrA,” i refer to the labor law as it exists today. The NIra / The f irst of the alternative legal regimes is the national industrial recovery Act (nirA) of 1933, which was the first attempt in the United states to give workers the right

- 18. to act in concert without employer interference and to encour- age collective bargaining. The theme of the Act, as stated in its preamble, was to replace “free competition” with managed “fair competition.” The nirA’s legal structure is known as corporatism. Cor- poratism emphasizes cooperation among interest groups or constituencies—especially labor and capital—and between those constituencies and the government. One problem with this scheme was that unions represented only a small percentage of the private labor force at the time. Without labor unions that broadly represent employees’ interests, industry codes would likely be unbalanced, reflecting only the interests of business. To provide a countervailing power to corporations, the nirA actively encouraged unionization. As a result, union member- ship grew exponentially in the period following the adoption of the nirA. Essentially, the economic goal of the nirA legal regime was to cartelize industry in order to prevent price and wage competi- tion from feeding deflation. Although the term “cartel” was not explicitly used, it was this feature that encouraged corporations to participate. At the heart of the nirA’s labor policy was section 7(a), which required that each code recognize the rights of employ- ees “to organize and bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing free from employer interference.” section 7(a) was breakthrough legislation for the union movement, pro- viding labor the right to organize and to do so without interfer- ence from employers. Most importantly, the nirA held out the promise of a truly cooperative relationship between labor and capital. By

- 19. equalizing pay across competing firms, unions took wages out of the price competition. The incentive to reduce wages and then prices to gain market share was no longer possible or profitable. Cutting spring 2014 / Regulation / 23 prices would violate the nirA’s codes of conduct. Moreover, the extra revenue provided by the higher prices could pay the higher union wages. High union wages thus did not put unionized firms at a competitive disadvantage. Management associations and labor unions worked together to form codes of behavior that prevented competitive cost cutting. The nirA experiment ended when the Act was declared uncon- stitutional by the U.s. supreme Court. in the case Schecter Poultry Corporation v. United States, the Court held that the code- making authority conferred by the nirA was an excessive delegation of legislative power and therefore unconstitutional. With its emphasis on fair competition, the nirA is against the spirit of free competition embodied in neoclassical economics. And as a legal regime, the nirA failed to work effectively. rather than attempting to reform the nirA, president Franklin roosevelt made the important political decision to let it become a brief footnote in American economic history. Wagner act / After the nirA was declared unconstitutional, a second attempt to calm industrial strife was made with the 1935 passage of the national Labor relations Act, better known as the Wagner Act. The heart of the legislation, section 7, was largely a carryover from section 7(a) of the nirA. Workers were

- 20. given a right to join labor organizations, bargain collectively, and engage in concerted activity such as strikes without “interference, restraint, or coercion” by management. The nLrA provided a detailed set of rules for both union recognition and collective bargaining. it forbade many employer tactics that discouraged unionization, set up machinery for determining the union des- ignated as the bargaining agent of the employees, and directed employers “to bargain collectively” with the chosen representa- tives in good faith. To achieve its goal of promoting industrial peace, the Wagner Act provided for a legal strike mechanism that channeled con- certed activity into a peaceful form. Employees were given the right to strike, but that right was required to be exercised in a peaceful fashion. The Act favored collective bargaining as the preferred form of the employment relationship and favored spreading collective bargaining throughout the economy. With the Wagner Act favor- ing unionization, if all firms in an industry were to unionize, the competitive pressures for firms to compete based on differences in costs would be reduced. The advantages of higher prices and higher wages, promised by the nirA, might be gained without the cumbersome structure and questionable constitutional legality of the nirA. Again, higher prices would fund the higher wages with the associated economic inefficiencies promoted by the nirA. The cooperative spirit between employers and unions envi- sioned by senator Wagner, however, was an impossible dream from the beginning. Without the government assistance to

- 21. cartel- ize labor and product markets provided by the nirA, the Wagner Act could only take wages out of competition if all firms in the industry were unionized and if wages were bargained at the industry level. Under the best of circumstances that would take time to develop. Thus, from the outset, staying nonunion under the Wagner Act gave firms much lower labor costs, negating any incentive to cooperate with unions. Taft-Hartley amendments / Most of the changes brought by the Taft-Hartley Amendments of 1947—the third of the four legal regimes—reduced the scope and effectiveness of the economic weapons available to the union in organizing new workers. Criti- cally, Taft-Hartley replaced the “closed shop” of the Wagner Act with the “union shop.” Under the new rules, prospective employ- ees did not need to be members of a union as a condition of employment. instead, the collective bargaining agreement could require that an employee join the union and was given at least 30 days from the date of hire to join. Although the loss of closed shop status was important to unions, it was minor compared to the effect of the “open shop.” The new section 14(b) permitted states to pass “right to work” laws mandating the “open shop.” in the open shop, employees hired into a bargaining unit job did not have to join the union or pay dues. The effect of the right- to-work laws, which were especially popular in the south, was to make it much more difficult for a union to organize and sustain bargaining units across an entire industry. Competing on wages was back as a business strategy.

- 22. in addition, Taft-Hartley added a list of unfair labor practices by unions to balance the list of unfair labor practices by employers in the Wagner Act. Taft-Hartley also added a new section 8(c) to clarify that employers had the right to express their views about unionization in response to a union organizing drive. The main effect of Taft-Hartley was to limit the spread of unionization. The relative difficulty of organizing, as well as the ban on the “closed shop,” guaranteed that there would be a vibrant nonunion sector, especially in the “right-to-work” states that required an “open shop.” Consequently, the legal regime of the Taft-Hartley Act has a nonunion sector competing actively with a union sector. The nonunion sector / The fourth legal regime is the patchwork of employment laws that regulate today’s nonunion sector. The employees in this sector do not have the benefits of an enforce- able contract, or of “just cause”–type job security, and they do not have a bargaining agent to represent their interests before the employer. This legal regime has two components. The first is the employment-at-will doctrine, which governs the norms of the workplace. The second is a set of government mandates such as the Fair Labor standards Act (FLsA); the Occupational, safety, and Health Act (OsHA); and the Employee retirement income security Act (ErisA); as well as Title Vii and other anti- discrimination laws. The employment-at-will doctrine effectively operates as a jurisdictional boundary. The effect of allowing an employer to 24 / Regulation / spring 2014

- 23. L a B O R discharge a worker at-will is that the employee cannot contest that decision in court. if taken literally, this rule may appear to promote employer opportunism and unfairness. Yet employment- at-will survives. What explains the almost universal fact that the nonunion employment relationship works without use of an enforceable contract for most of its terms? One possible answer is that employers are able to exploit their superior bargaining power over employees and impose this unfair arrangement. But that begs the question of why the nonunion sector seems tranquil today, rather than having a labor force eager and ready to unionize. perhaps nonunion employers can offer a pay and job security package that is attractive because it has lower costs than the unionized firms with which they compete. Understanding this point takes us to the neoclassical theory of the firm. The key point here is that in addition to higher union pay, col- lective bargaining is a high-cost mechanism for providing worker protection against employer opportunism. simply put, collective bargaining is very expensive because of its high transaction costs. in general, when transaction costs are high and contract enforce- ment is expensive, the economic relationship is brought inside the firm, where the parties are governed by the intra-firm hierarchical

- 24. governance structure. From the perspective of transaction cost theories, the decision to bring relationships within the firm is the decision to opt for the intra-firm governance structure over contractual governance within markets. With the single exception of the collective bargaining contract, the decision to bring an activity inside the firm means that the activity will not be governed in most of its particulars by con- tract terms. What then explains the fact that employers do not use the employment-at-will doctrine to act opportunistically and take advantage of their work force? As an empirical matter, employment-at-will is today an accepted part of the nonunion employment relationship, at least to the extent that it is not a seri- ous topic of labor law reform at either the national or state level. What explains the relative lack of employer opportunism in today’s nonunion sector? The answer is to be found in the unique nature of the employment relationship: it is an intensive repeat- play game. Monitoring is costly and thus incomplete. it is now well known that informal norm governance works best in such situations because self-help methods are much more effective. in this situation, it is the firm that arguably lacks bargaining power, since the remedy—increased monitoring—can be prohibitively expensive for the same reasons that contract writing is prohibi- tively expensive. The employment relationship is typically marked by the parties investing in their match. Firm-specific investments create a wedge between the employee’s value to her current employer versus her

- 25. value to a new employer. The contract is self-enforcing because both sides then lose their investment if the relationship is termi- nated early. in addition to the self-enforcing structure of norms, other factors are also at work. For instance, reputational effects can be a strong deterrent to employer opportunism. The ultimate deterrent to employer opportunism, however, is the threat effect of unionization. A nonunion firm will become much less profitable if unionized. Wage and benefits will likely be raised above competitive levels and the firm will have the transac- tion costs of negotiating a collective bargaining agreement that will also impose restrictions on its ability to manage its work force unilaterally. The second component of the nonunion legal regime is the extensive set of government mandates such as the FLsA, OsHA, and ErisA, as well as Title Vii and other antidiscrimination laws. Mandates such as ErisA and OsHA serve to remedy potential problems of information asymmetries. Mandates such as mini- mum wages, child labor prohibitions, and discrimination-free employment serve a different function. rather than correcting a market imperfection, they impose a public moral standard. such regulations impose minimum standards on the theory that some market-determined outcomes are unacceptable as a matter of national policy. AccOMPLiSHiNG THE GOALS OF THE NLRA Which legal regime best accomplishes the goals of the nLrA? The nirA receives some credit for being the first federal labor law legislation to provide for the right to engage in lawful concerted

- 26. activity: both to unionize and to strike without interference from employers. As a practical matter, however, the nirA failed on the ground, and the problems showed up almost immediately. price- fixing proved difficult to accomplish. noncompliance begot further noncompliance, as code-abiding business executives began to feel the pinch of competition from cheating firms. The hoped-for stable higher prices were not achieved. The nirA was no more successful in labor relations than it was at fixing prices. in the nirA framework, unions and business were expected to exercise self-restraint in their bargaining demands in order to support national priorities. That did not happen. The historical record of strike activity during the brief nirA era illus- trates the failure of the law to reduce industrial strife. instead of providing for greater labor stability, the number of workdays lost to strikes tripled over the first three years of the nirA. The nirA does much better with the goal of equalization of bargaining power. On the procedural element, the nirA suc- ceeded because the percentage of workers from the private sector belonging to unions increased. On the substantive element, The nirA was also successful. Although the exact premium differs by industry and over time, the evidence uniformly supports the existence of a high union wage premium over the entire period studied here. Overall, the nirA scores high as the first major legislation to grapple with the problems of industrial strife and unequal bargaining power. Much more statutory work needed to be done,

- 27. but the nirA was a good first attempt. spring 2014 / Regulation / 25 achieving the Wagner act’s goals / One would expect that the Wagner Act would be successful in achieving its own goals. in fact, the record turned out to be mixed. With respect to indus- trial peace, the Wagner Act created a legal strike mechanism that turned many strikes from violent ones to non-violent ones. This was an important change. Although less threatening to the established order, industrial strife—which had already increased during the nirA years—increased further under the Wagner Act. rather than bringing industrial peace, the number of strikes and lockouts nearly doubled under the Wagner Act. There are several explanations for the worsening in industrial strife. First, particularly in the late 1930s, many new unions were forming, undertaking their organizing drives and bargaining for their first contract. second, the legal regime was particularly favor- able to unions. For example, the fact that there were no unfair labor practice standards restricting union action meant that the strike weapon could be used freely except as constrained by state law. Third, the aspirations of union leaders and workers increased along with the more favorable legal regime, and rising aspirations translated into more costly bargaining demands that were difficult to resolve without strikes. The jump in industrial strife went along with a sharp increase in union membership.

- 28. so while the Wagner Act was unable to reduce industrial strife, it was able to increase union representation. That is, while the first goal was proving unattainable, the second goal was being achieved. This underscores one of the themes of this article: the goals of the Wagner Act were potentially inconsistent. A potential inconsistency in the Act turns into an actual inconsistency once the substantive goal of equalizing bargaining power is taken into account. Concomitant with the increase in union density, the newly organized union members were able to achieve higher wages and thus gained the union wage premium. Herein lies the problem: who would pay for the higher wages? Under the Wagner Act, and unlike the nirA, firms would pay for the higher wages through reduced profits. Although firms might be able to pass on some of the wage increases to consumers, there is no reason to suppose that they could pass on the bulk of the increase. Consequently, employer opposition to unions was built into the Wagner Act. in summary, the Wagner Act scores high on the goal of equal- izing bargaining power. With respect to the key goal of industrial peace, however, the Wagner Act was not a success. strikes did become less violent compared to the strikes of the late 19th cen- tury, but violence was still a frequent feature of strike activity. in

- 29. addition, the level of strike activity increased dramatically, and this—combined with the continuing incidence of violence—was eventually deemed to be unacceptable. Whatever its success in promoting the bargaining power of workers, it was doomed to be replaced because it failed to achieve industrial peace. Taft-Hartley and the NLra’s goals / The Taft-Hartley Amendments transformed the original Wagner Act into a very different regime. it certainly changed the Wagner Act’s balance between employers and unions in favor of employers. it also supported the develop- ment of a vibrant nonunion sector in almost every industry, thus raising the likelihood of direct labor cost competition between union and nonunion companies. With respect to the goal of industrial strife, the post-Taft- Hartley nLrA has been much more successful than the Wag- ner Act. The average number of strikes, adjusted for the size of employment, dropped throughout the decades following passage of Taft-Hartley. During the 1970s, there was an average of 289 strikes per year involving 1,000 or more workers. This … MHR 6451, Human Resource Management Methods 1 Course Learning Outcomes for Unit VI Upon completion of this unit, students should be able to:

- 30. 8. Analyze the impact of different collective bargaining strategies on employee morale. Reading Assignment In addition to the articles and videos listed directly in the Unit VI Lesson, the following items are also required. In order to access the following resources, click the links below. Hurd, R. W. (2013). Moving beyond the critical synthesis: Does the law preclude a future for US unions? Labor History, 54(2), 193-200. Retrieved from https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?url=http://s earch.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direc t=true&db=bth&AN=87786622&site=ehost-live&scope=site Wachter, M. L. (2014). The striking success of the National Labor Relations Act. Regulation, 37(1), 20-26. Retrieved from https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?url=http://s earch.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direc t=true&db=bth&AN=95528882&site=ehost-live&scope=site Unit Lesson In order to access the following resource, click the link below.

- 31. College of Business – CSU. (2016, September 1). Collective bargaining [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/KZcuT1oM2GE To view the transcripts for this video, click here. Collective Bargaining and Employee Morale This unit begins with a rapid look back at the history of American trade unions and how the first friendly societies in the 18th century evolved and later began to tackle important issues such as minimum wage, health and safety conditions, discrimination, benefits, job security, strikes, and even challenges posed by new technologies of the 1980s and 1990s. As you watch the following archival footage, veterans of the labor struggles along with business and government officials reveal fascinating personal insights into labor’s sometimes violent origins and how it has altered the workplace over the past 200 years. This film can be viewed in the Films on Demand database within the CSU Online Library. You are encouraged to watch Segments 2 (Immigrant Labor), 3 (Labor Unions: A.F.L. and the I.W.W.), and 8 (Change in the Labor Market) in the video linked below. Gardner, E. T. (Producer), Angel, C. (Producer), & Boyd, K. (Director). (1994). Organizing America: The history of trade unions [Video file]. Retrieved from https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?auth=CAS &url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPla ylists.aspx?wID=273866&xtid=8049

- 32. To view the transcript of the video above, click here. Hopefully, after watching the video, you have learned a little more about the beginnings of the labor unions UNIT VI STUDY GUIDE Collective Bargaining and Employee Morale https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?url=http://s earch.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=8778 6622&site=ehost-live&scope=site https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?url=http://s earch.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=8778 6622&site=ehost-live&scope=site https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?url=http://s earch.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=9552 8882&site=ehost-live&scope=site https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?url=http://s earch.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=9552 8882&site=ehost-live&scope=site https://youtu.be/KZcuT1oM2GE https://online.columbiasouthern.edu/bbcswebdav/xid- 71368682_1 https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?auth=CAS &url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=273866 &xtid=8049 https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?auth=CAS &url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=273866 &xtid=8049 https://online.columbiasouthern.edu/bbcswebdav/xid- 71368687_1

- 33. MHR 6451, Human Resource Management Methods 2 and have an appreciation for the sacrifices endured by all during those tough economic times. Today, the American Bar Association (1997) and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) (n.d.) remind us that labor law is still linked to three significant federal statues: Relations Act (NLRA); -Hartley Act, also known as the Labor Management Relations Act (LMRA); and -Griffin Act, also known as the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA). The Wagner Act is a federal law that grants employees the right to form and join a union, promote and aid unions, select a union to act for them as their collective bargaining representative, and help them regarding workplace issues. Additionally, employees have a right to not engage in concerted activities under this act. These rights are provided to employees working for employers in the private sector who are covered by the NLRA. This excludes employees of airlines, railways, independent contractors, farmworkers, domestic workers, supervisors, and managers. The National Labor Relations Board administers the Wagner Act and investigates charges of unfair labor practices by employers and

- 34. unions (American Bar Association, 1997; Industrial Workers of the World, n.d.; Ivancevich, 2010). Congress amended the NLRA, also known as the Wagner Act, with the Taft-Hartley Act. This act has two purposes: to reduce industrial arguments and to restrict the power of labor unions. It establishes guidelines for employee and employer relationships and protects employees from unfair labor practices by unions (National Labor Relations Board, n.d.). Congress passed the Landrum-Griffin Act, also known as the LMRDA, to protect individual members from illegal practices by the unions and by employers as well. It gives union members rights such as the right to nominate individuals for union office, vote in the elections, and attend union meetings. It ensures that union accounts and records are available to all union members. In an effort to eliminate what was referred to as sweetheart contracts, where union and management agreed to terms that benefitted their own interests but allowed poor working conditions for the workers, the union must submit an annual financial report to the Secretary of Labor. Additionally, the employer is required to report any payments or loans given to the union, union officials, or employees (American Bar Association, 1997). Collective Bargaining: What is it? At the center of the employer-employee relationship is the collective bargaining process. As the exclusive agent for the employees, it is the union’s duty to negotiate a collective bargaining agreement with the employer. The employer and union are required by the NLRA to bargain in good faith concerning employee

- 35. wages, benefits, hours, and terms and conditions of their employment in order to reach an agreement. Refusing to bargain in good faith violates the law. Once the union has been elected, the employer cannot negotiate with anyone else—not directly with employees or with another union (American Bar Association, 1997; Carrell & Heavrin, 2010). Rather than negotiating each time an issue occurs, the terms and conditions of employment are set down in a collective bargaining agreement (CBA). Ideally, both management and the union agree on the duties, rules, and benefits that will govern the workplace relationship between management and employees for a set period of time (e.g., three years) (American Bar Association, 1997). Since the agreement will be in use over a period of time, it is imperative that both parties, management and union, bargain in good faith and understand their role in the collective bargaining process. There are several phases of the bargaining process. The first is preparation; it is extremely important that both parties do their homework by analyzing the data for their proposals, anticipating the other’s proposals, selecting their bargaining items, and planning their strategy. Next is the actual bargaining stage, where ground rules are established and an exchange of demands, proposals, and counterproposals are made. The resolution stage is where an agreement is reached. The union members ratify the contract, or if the parties find themselves at an impasse over the terms and conditions of employment, then it is often resolved through mediation or arbitration. When these measures fail, a lockout or strike may occur, and even hiring replacement employees may happen until a resolution can be reached. Having a unified strategy and being prepared usually keeps

- 36. this worst-case scenario from happening (Carrell & Heavrin, 2010). MHR 6451, Human Resource Management Methods 3 One industrial relations professional describes collective bargaining as having four phases: planning, face-to- face negotiations, coming to agreement, and implementing the agreement (Queen’s IRC, 2014). In the following short video, Ann Grant of Queen’s Industrial Relations Centre (IRC) talks about the collective bargaining process, and she describes what parties should expect when trying to reach a collective agreement. Queen’s IRC. (2014, February 25). What are the four phases of collective bargaining? [Video file] Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F02opoWS6bU&feature=yo utu.be To view the transcript of the video above, click here. Collective Bargaining: What’s Discussed at the Bargaining Table? The National Labor Relations Board established mandatory subjects that must be discussed if brought up by either party during collective bargaining. It is the duty of management and the union to negotiate mandatory

- 37. issues such as wages, hours, benefits, vacations, profit sharing, drug testing, layoffs, transfers, and recalls (American Bar Association, 1997; Carrell & Heavrin, 2010; National Labor Relations Board, n.d.). Nonmandatory or volunteer subjects can be discussed only if both parties agree to discuss them; there is no duty to negotiate issues such as what products the company will offer, how much will be spent for advertising, or how much will be put into the marketing budget. However, if the company and union enter into a negotiation and agree on a nonmandatory subject under the CBA, they must adhere to the conditions. The last categories are illegal subjects, and even if both parties agree to discuss them, they cannot be negotiated. These would include topics such as discriminatory treatment, whistleblowing, and closed shop. The CBA includes three provisions: just cause clauses, grievance and arbitration clauses, and union security clauses (American Bar Association, 1997; Carrell & Heavrin, 2010; National Labor Relations Board, n.d.). Let’s hear what Stephen Cabot, a management-labor expert, says about the permissive and mandatory subjects in collective bargaining. As you listen to Cabot’s advice, be thinking critically about the approach or type of strategy he is suggesting. Cabot, S. J. (2009, November 9). Stephen Cabot’s labor strategy survival seminar – Bargaining subjects [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZCqP0AzAOxk&feature=yo utu.be

- 38. To view the transcript of the video above, click here. Collective Bargaining: Types of Strategies There are commonly two types of strategies used in collective bargaining: distributive bargaining and interest- based bargaining (IBB). When selecting which type of strategy to use, it is most important to review the specific issues to be negotiated, the people involved, and the context of the discussions. If only one issue will be negotiated, then a distributive bargaining process would probably be used. If there are multiple issues and there is a positive bargaining relationship between the parties, a more collaborative approach, such as IBB (also referred to as a win-win approach), would be used. Distributive bargaining is defined as a negotiation process that has the goal of coming to an agreement over how resources should be allocated. There are three components to this win-lose approach: resource, bargaining process, and the immediate interaction and negotiation, with little concern for past or future relationships. In collective bargaining, the reality is that both parties are fully aware that they may be negotiating in the future and want to accomplish their goals in good faith. They

- 39. do, however, start the process with different strategies. IBB is a mutual gains or win-win approach that looks for logical trade-offs and is referred to as an expanded- pie approach, whereas the distributive bargaining is a fixed-pie approach. IBB, also called integrative https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F02opoWS6bU&feature=yo utu.be https://online.columbiasouthern.edu/bbcswebdav/xid- 71368682_1 https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCDcvqcT2nPmDXX0FAbr_ RjA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZCqP0AzAOxk&feature=yo utu.be https://online.columbiasouthern.edu/bbcswebdav/xid- 71368681_1 MHR 6451, Human Resource Management Methods 4 bargaining, strives to create value for both sides and claim as much value as possible for personal interests. IBB pursues principled negotiation and strives to separate the people from the problem, focuses on interests rather than positions, and creates options for mutual gain. For examples of this and other differences between distributive and IBB, view the following video: Professional Development Training. (2013, September 24). Negotiation-2 strategies [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/PO3Mv8dGbJM

- 40. To view the transcript of the video above, click here. Most collective bargaining has elements of both types of bargaining. It is important to stay focused and not become too greedy; those who are negotiating for the employees or the company have reputations to uphold. Here is some good advice from a veteran negotiator; watch the short video indicated below. 101therealest. (2015, December 3). 7.Distributive bargaining and the dangers of being greedy [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/b3XpVlTQ1Xo To view the transcript of the video above, click here. Collective Bargaining: The Opening Session and Recognizing Bargaining Tactics The opening session of collective bargaining establishes the details of the process, and if the parties have not bargained before, more time is spent introducing members, designating leaders, and setting the ground rules. If the parties have negotiated formerly, a general conversation and introductions take place, and each party states their intention to use a traditional or collaborative process (Carrell & Heavrin, 2010). The following brief article, which you can access by clicking the link in the reference below, provides a glimpse into tactics used by members of management who are intending to use the traditional process of collective bargaining: Outsmarting the "stealth" union organizer. (2010). Management

- 41. Report for Nonunion Organizations (Wiley), 33(8), 5. Retrieved from https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?url=http://s earch.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direc t=true&db=bth&AN=52427363&site=ehost-live&scope=site The importance of an opening statement when preparing an interest-based strategy should not be underestimated. Both parties need to paint the big picture of the negotiation, the past relationship, current issues, intentions, and ground rules, and parties should exchange the key economic and non-economic issues that must be resolved to reach a settlement (Queen’s IRC, 2013). To see how understanding the dynamics and skills for negotiating a collective agreement can impact the outcome of the collective bargaining process, watch Queen’s IRC facilitator Gary Furlong discuss this issue. Queens IRC. (2013, August 12). How can the dynamics of collective bargaining impact the outcome of your negotiations? [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/hOBORmAETxk To view the transcript of the video above, click here. Unfortunately, if distributive bargaining is used by one party, the other party must follow suit, or they stand to lose it all. If distributive bargaining is used, the other party should anticipate some bargaining tactics in case conflict arises. It is good to show patience and to remember that goals are interdependent, and neither side can be successful without a future healthy relationship. Another

- 42. tactic is the packaging of issues to be negotiated, and this tactic can establish trust and will allow for gains on both sides. The same is true of throwaway items; some may have value to one side but may not have value to the other side. Caucusing, flexibility, compromise, and saving face are all important as well; however, they can take up valuable time and must be carefully executed (Carrell & Heavrin, 2010). To be better prepared for any traditional bargaining you may find yourself in, watch the quick video indicated below. Arden, D. (2013, August 11). The 7 mistakes people make when they negotiate [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/PO3Mv8dGbJM https://online.columbiasouthern.edu/bbcswebdav/xid- 71368690_1 https://youtu.be/b3XpVlTQ1Xo https://online.columbiasouthern.edu/bbcswebdav/xid- 71368683_1 https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?url=http://s earch.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=5242 7363&site=ehost-live&scope=site https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?url=http://s earch.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=bth&AN=5242 7363&site=ehost-live&scope=site https://youtu.be/hOBORmAETxk https://online.columbiasouthern.edu/bbcswebdav/xid- 71368684_1 MHR 6451, Human Resource Management Methods 5

- 43. https://youtu.be/BldEUM1Ha94 To view the transcript of the video above, click here. Sometimes, tactics reach the general population and have lasting effects on both parties. For an example of this, watch Segments 4 and 5 in the video linked below. Moyers, B. (Writer), Winship, M. (Writer), & Diego, K (Director). (2009). United Steelworkers’ Leo Gerard/earmark abuse [Television series episode]. In T. Casciato (Executive Producer), Bill Moyers Journal. Retrieved from https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?auth=CAS &url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPla ylists.aspx?wID=273866&xtid=40177 To view the transcript of the video above, click here. For an appreciation of what slows down negotiations and to learn how each party can more effectively negotiate by understanding the way the opposing party thinks at the bargaining table, watch the following video. Candian HR Reporter. (2012, April 16). Overcoming mental barriers in collective bargaining [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/688KDSeQHGo To view the transcript of the video above, click here. Collective Bargaining and Employee Morale

- 44. In Reframing Organizations, Bolman and Deal (1997) stress the importance of having organizations build a thoughtful human resource (HR) philosophy that clearly explains how to treat people. They provide many examples of successful organizations that diligently enforce their philosophy into the corporate structure, provide incentives, and develop ways to measure the management of HR. This philosophy is achieved by investing in people—hiring the right people; paying the employees well; providing guidance and direction, job security, training, and education; promoting from within; and sharing the wealth through profit or gain (sharing or employee ownership). These are all necessary elements of an HR philosophy; however, it is the work itself that provides the opportunity for the autonomy, influence, and intrinsic rewards that skyrocket morale. By empowering employees with autonomy and participation and by redesigning their work with a focus on job enrichment and teamwork, equality and self-efficacy is ensured (Bolman & Deal, 1997). There have been many HR scholars; one such scholar is Frederick Herzberg due to his work on the importance of achievement, responsibility, and recognition. Herzberg (1969) called these factors motivators, and his research showed that remarkable results can happen when people are given the authority to influence their working conditions. Bolman & Deal (1997) relate a classic study captured by Whyte in 1955. In a reengineering process, a group of women who painted toy dolls manually in a toy factory were asked to use a new system where they took a

- 45. toy from a tray, painted it, and then put it on a passing hook. They were given an hourly rate, a bonus for the group, and a learning bonus. Management had no expectation of a system problem, but the results were disappointing, and the employees’ morale was poor. The workers protested that the hooks moved too fast and the environment was too hot. After hiring a consultant, the managers agreed to meet with the women face to face, and as a result of the meeting, management decided to bring in fans. To their surprise, morale improved. After several meetings, the women made a radical request: They wanted to control the speed of the belt. Against the engineer’s objections, management decided to try the women’s suggestion. They prepared a production schedule that was logical to their work day. The belt was slow at the start of the shift, and as the employees warmed up, the speed of the belt increased; the speed of the belt slowed again right before lunch and so on and so forth. The results increased production beyond anyone’s expectations; the women’s bonuses were giving them more income than other employees who were more highly skilled. The women’s higher pay and production was disruptive, and other workers protested. To still the waters, management went https://youtu.be/BldEUM1Ha94 https://online.columbiasouthern.edu/bbcswebdav/xid- 71368679_1 https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?auth=CAS &url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=273866 &xtid=40177 https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?auth=CAS &url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=273866 &xtid=40177

- 46. https://online.columbiasouthern.edu/bbcswebdav/xid- 71368680_1 https://youtu.be/688KDSeQHGo https://online.columbiasouthern.edu/bbcswebdav/xid- 71368688_1 MHR 6451, Human Resource Management Methods 6 back to the engineers’ fixed speed; production decreased, morale fell, and most of the women quit. This makes one wonder if the cost of redesigning other positions would have outweighed the benefits they would have gained? Research that extended Herzberg’s ideas on job enrichment was conducted by Hackman & Oldham (1980) and indicates that for redesign to be successful, three factors need to be present. First, people need to identify their work as meaningful and worthwhile, and they must see it as a whole rather than seeing it as a part of something. They also need to be able to use discretion and judgement and be accountable for the results. Finally, they should be given feedback that will allow them to improve. One popular program of this time period that is still being used today is Total Quality Management (TQM), which combines Eastern and Western philosophies and encourages bottom-up critical thinking. Another result of research done on job enrichment is that it has a stronger impact on quality than productivity, which makes sense if you think about the satisfaction one gets

- 47. from a job well done versus just doing more work (Lawler, 1986). Most of the successes with teams come from self-managed, autonomous work groups who are given responsibility for a meaningful whole such as a product or a complete service. This was not always acceptable to management or unions on many levels, mostly because they did not want to lose prerogatives they were currently enjoying, and they believed their involvement was essential to success. However, things are changing; one of the world’s first plants was built by Volvo in Kalmar, Sweden, to accommodate self-managing work groups (Bolman & Deal, 1997). When it comes to worker morale, they prefer autonomy and more power to less, and when they are allowed to gain influence, they want more. The question then remains, will management and union leaders bargain for and encourage the environment that provides employees with the highest morale? Collective Bargaining and its Future This unit closes with looking at where the union movement is today and the trends in labor laws for tomorrow. Union membership may be down; however, unions have been influential, although not successful, in pushing Congress to pass the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), which allows employees to vote using authorization cards to have a union and to bypass formal elections. Speculation as to what would have happened if the EFCA had been passed, as well as other failed efforts for union revitalization, is discussed in the Richard Hurd (2013) article, “Moving Beyond the Critical Synthesis: Does the Law Preclude a Future for US Unions?,” which is listed in the required reading section of this unit. Another trend is creating new strategies for cooperative labor

- 48. relations. These efforts can lead management to share information with unions, and this encourages unions to be more cooperative with management, which, consequently, ensures a more competitive organization. An excellent example of this can be seen in the following video. You are encouraged to watch Segments 1 and 2 in the video indicated below. Smith, H. (Producer). (1998). Management combines forces with unions-Northwest Airlines [Television series episode]. In Surviving the Bottom Line with Hedrick Smith. Retrieved from https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?auth=CAS &url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPla ylists.aspx?wID=273866&xtid=7827 To view the transcript of the video above, click here. For a different viewpoint, go to the General OneFile database, and read the article by M. L. Wachter, titled “The Striking Success of the National Labor Relations Act,” which is listed in the required reading section for this unit. Despite a continuing decline of union membership in America, Labor Secretary Thomas Perez remains optimistic about the future of organized labor. Watch as the Labor Secretary reflects on the future of unions in this interview excerpt with PBS News Hour: PBS News Hour. (2013, September 2). Labor secretary reflects on the future of unions [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/vq_EB5MxhFo

- 49. To view the transcript of the video above, click here. https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?auth=CAS &url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=273866 &xtid=7827 https://libraryresources.columbiasouthern.edu/login?auth=CAS &url=http://fod.infobase.com/PortalPlaylists.aspx?wID=273866 &xtid=7827 https://online.columbiasouthern.edu/bbcswebdav/xid- 71368692_1 https://youtu.be/vq_EB5MxhFo https://online.columbiasouthern.edu/bbcswebdav/xid- 71368689_1 MHR 6451, Human Resource Management Methods 7 Another positive but varying perspective comes from Sara Horowitz, an international lawyer and founder of the Working Today & Freelancer’s Union, a leading organization of independent workers. This labor expert sees a bold new role for unions in the new economy, and Horowitz shares her outlook by answering two interesting questions: What is the role of unions in the new economy? Does labor hamper industrial growth? Find out the answers in this short video: Big Think. (2012, April 23). Sara Horowitz envisions the future of unions [Video file]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/X9rP9aGw4xE

- 50. To view the transcript of the video above, click here. References American Bar Association. (2006). The American Bar Association guide to workplace law (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Random House. Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (2013). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership (5th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. Carrell, M. R., & Heavrin, J. D. (2010). Labor relations and collective bargaining: Private and public sectors (10th ed.). New York, NY: Pearson. Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980). Work redesign. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley. Herzberg, F. (1969). Work and the nature of man. New York, NY: Crowell. Hurd, R. W. (2013). Moving beyond the critical synthesis: Does the law preclude a future for US unions? Labor History, 54(2), 193-200. Industrial Workers of the World. (n.d.). The basic labor laws (United States of America). Retrieved from

- 51. http://www.iww.org/organize/laborlaw/Lynd/Lynd3.shtml Ivancevich, J. (2010). Human resource management (11th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Irwin. Lawler, E. E., III (1986). High involvement management: Participative strategies for improving organizational performance. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. National Labor Relations Board. (n.d.). National Labor Relations Act. Retrieved from https://www.nlrb.gov/resources/national-labor-relations-act Queens IRC. (2013, August 12). How can the dynamics of … Moving beyond the critical synthesis: does the law preclude a future for US unions? Richard W. Hurd* Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA This retrospective essay on Tomlins’ The State and Unions assesses the durability of his observations in light of developments over the past quarter century. The decline of unions in the context of minimal protections offered under contemporary labor law seems to fit Tomlins’ thesis that the New Deal offered only a counterfeit liberty to labor. A brief review of

- 52. failed efforts at union revitalization demonstrates that labor’s waning fortunes are as much a sign of institutional rigidity and internal weakness as result of external constraints. Any current semblance of liberty offered to the U.S. working class is indeed counterfeit, but the source of fraud is the full set of neoliberal economic policies, not the narrow constraints of labor law alone. As Jean-Christian Vinel reminds us, when Christopher Tomlins’ The State and Unions was published in 1985 it was embraced by left academics as a ‘devastating analysis of the labor relations regime erected by Progressive and New Deal reformers.’ Indeed Tomlins’ portrayal of the original National Labor Relation Act (NLRA) as the foundation of a set of ‘legal rules and institutional constraints’ that would curb workers militance and ultimately weaken the labor movement was particularly pertinent in the mid-1980s. At that juncture, private sector union density was in sharp decline, and even prominent labor leaders seemed to be echoing Tomlins with their outspoken criticism of the law and the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

- 53. Vinel appropriately positions Tomlins contribution within an interdisciplinary paradigm that he labels the ‘critical synthesis’ encompassing New Left social scientists and Critical Legal scholars. Indeed those of us with roots in the New Left greeted Tomlins work as a vindication of our skepticism regarding the New Deal and its supposed left- progressive tilt, and as a piece of thorough scholarship that confirmed our own less well- framed arguments. 1 Of course The State and the Unions was not met with universal praise, but like all good scholarship served as a catalyst for healthy debate. As noted by Vinel, among the critics was Melvyn Dubofsky, who questioned whether a militant labor movement would have emerged even if conflict had not been channeled into the bureaucratic procedures of the NLRB. Dubofsky went beyond this basic criticism (which was raised as well by others at the time) and also disagreed with Tomlins’ main thesis, arguing instead that the law and its

- 54. administration can be understood only in the broader context of shifting economic and political power relations. 2 The latter point has been developed more fully by James Gross q 2013 Taylor & Francis *Email: [email protected] Labor History, 2013 Vol. 54, No. 2, 193–200, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2013.773147 in his three-volume history of the NLRB, the first two of which were published before Tomlins’ book. 3 Perhaps more intriguing as we look back on Tomlins’ contribution is the reaction of Craig Becker in a full-length Harvard Law Review article, relevant for both its content and its author. Parallel to Dubofsky, Becker argued that Tomlins failed to appreciate internal complexities of the labor movement and its responses to the NLRA. Furthermore, although

- 55. agreeing that the New Deal ‘was hardly an unalloyed victory for unions,’ Becker chided Tomlins for dismissing ‘far too hastily the rights the NLRA afforded labor.’ 4 Given Becker’s recent position on the NLRB (as an Obama recess appointee loudly condemned by the Republican right), a careful read of his reaction to The State and the Unions should prove valuable for those who are monitoring the actions of the Board a quarter of a century later. Indeed, even those of us who praised Tomlins in the mid-1980s have cause to re- evaluate the efficacy of his damning of the NLRA. Vinel captures this revised perspective in his thoughtful essay when he notes, ‘Thirty years of conservative rule have fundamentally changed the debate on the merits of the system created by the pluralists of the 1930s.’ The New Deal may have done less to create a just society than recalled by champions of Franklin Delano Roosevelt among historians and labor relations academics,

- 56. but it most certainly offered more to workers and unions that the current neoliberalism that dominates the thinking and policies of both major political parties. To fully appreciate how a recasting of Tomlins may make sense in light of what has transpired over the succeeding quarter century, we need to go beyond Vinel’s rendering and consider developments in union strategy and practice, including the push for labor law reform that has dominated the political agenda of unions since before the Reagan era. Union transformation: the search for a militant working class As if on cue from Tomlins and the publication of his book, 1985 was a pivotal year for the labor movement with the release of the American Federation of Labor – Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO’s) blueprint for revitalization, The Changing Situation of Workers and Their Unions. The culmination of a strategic planning process that involved the presidents of most major unions, The Changing Situation, offered five sets of recommendations, two of which are relevant here: increase

- 57. member participation/activism and improve organizing methods. 5 Initiatives to address members’ apathy were initially framed as internal organizing, then later as the organizing model that was contrasted with the servicing model, or the traditional insurance agent approach to union representation. 6 Most unions endorsed the organizing model at least rhetorically, and several initiated broad-based efforts to inspire activism and militancy. For example, the Communications Workers of America devoted considerable resources to a mobilization structure that increased member involvement in both workplace actions and coalitions with other unions and community organizations. 7 Similarly, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) designed a contract campaign framework to increase militancy during contract negotiations, 8 and encouraged

- 58. locals to experiment with approaches to implement the organizing model in all aspects of their work. On the external organizing front, the AFL-CIO created the Organizing Institute (OI) to recruit, train, and place union organizers. The OI adopted a grassroots style that paralleled R.W. Hurd194 the mobilization efforts being developed to increase member activism. This bottom-up organizing contrasted with the traditional method of selling union representation to prospective customers. By the mid-1990s there were hundreds of OI trained organizers working in the labor movement, and the OI method of member recruitment was accepted as the preferred ‘model’ of organizing. Perhaps because of the parallels to the mobilization of current members being promoted simultaneously, it became common for those in union circles to refer to the OI style as the organizing model. Thus, for the past 15 plus years, the

- 59. term has been used indiscriminately to refer to both internal and external organizing with an activist core. 9 In spite of nearly a decade of concerted efforts to build an activist culture, union density continued to decline into the mid-1990s. Frustration among the more engaged elements of the labor movement culminated in a successful effort to oust long time President Lane Kirkland and elect a new slate of AFL-CIO officers in 1995: John Sweeney, Richard Trumka, and Linda Chavez-Thompson. This ‘New Voice’ team promised to ‘organize at a pace and scale that is unprecedented.’ 10 Under the strategic guidance of Richard Bensinger, who moved from the OI to become Organizing Director, a blueprint for growth was adopted and vigorously promoted as ‘Organizing for Change, Changing to Organize.’ 11

- 60. These efforts at revitalization are relevant to an assessment of Tomlins’ enduring contribution because they offered the potential for radical change in organized labor even within constraints of the NLRA framework. Indeed specific unions and groups of unions began to look tantalizingly like a left, militant labor movement. Many of us in scholarly circles reported, analyzed, and hailed the transformation in progress as the beginning of a new social movement unionism, or social justice unionism. 12 The enthusiasm was never fully justified. It became clear within relatively few years that the internal application of the organizing model was proving to be difficult except during the period immediately preceding the expiration of a collective bargaining agreement. Even then, mobilization required careful planning and intense efforts by staff and elected leaders. Burnout was a common problem, and rank- and-file enthusiasm was difficult to sustain. It seemed that union members did not have a taste for perpetual

- 61. warfare, preferring stability rather than class struggle. 13 External organizing seemed to offer more potential, especially with enthusiastic leadership from John Sweeney and the AFL-ICO. But the Changing to Organize agenda included not only a grassroots approach (which proved threatening to elected leaders at the local level) but also a substantial shift of resources. Individual national unions were happy to proclaim support for the organizing priority, but union officers jealously guarded their authority over resource allocation, organizing strategy, target selection, and all decisions regarding coordination with other unions. Efforts by the AFL- CIO to take the strategic lead and build a movement wide growth agenda were effectively rejected. 14 The end result was continued decline, and growing frustration among those unions that were most committed to the organizing priority. Dissension came to a head in 2005 when the SEIU led the exodus of six key unions from the AFL-CIO to form Change to Win