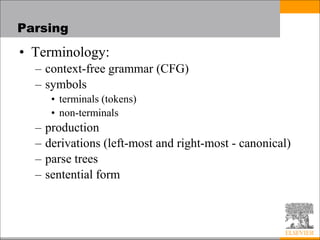

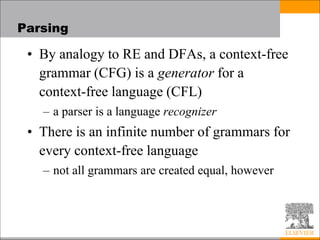

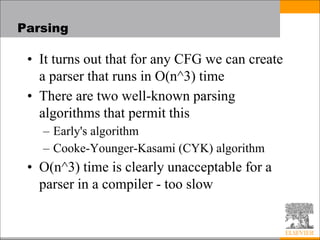

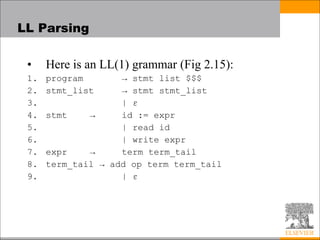

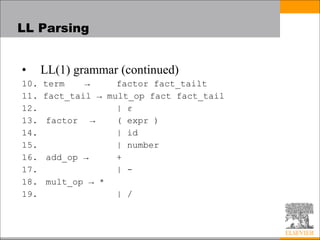

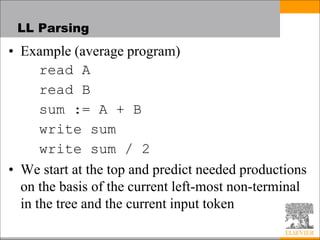

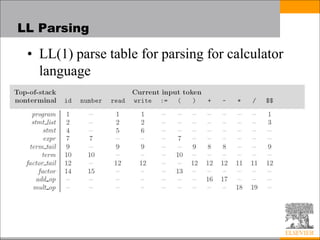

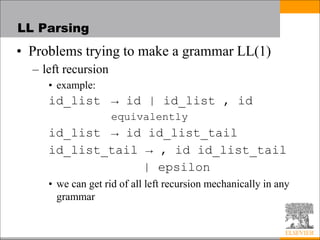

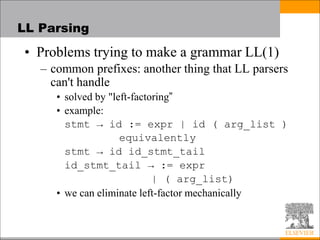

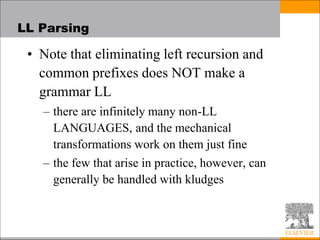

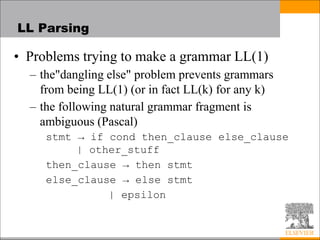

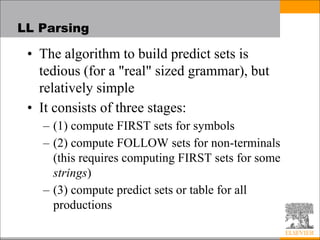

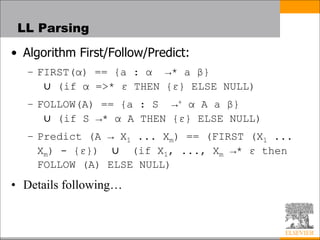

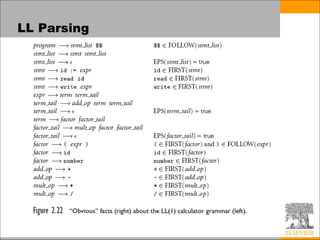

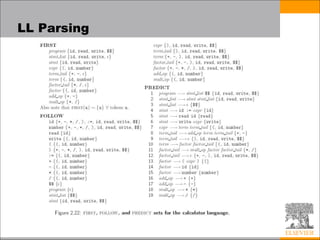

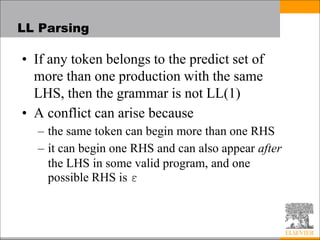

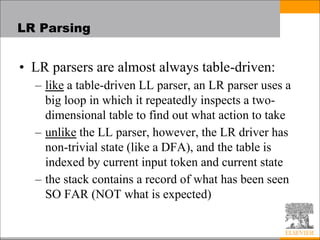

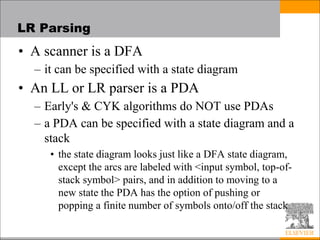

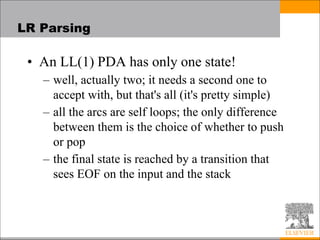

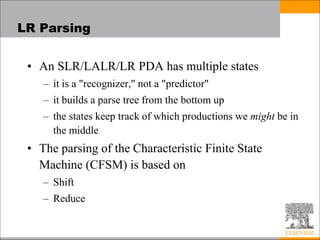

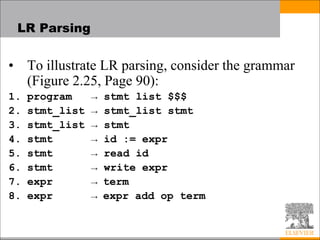

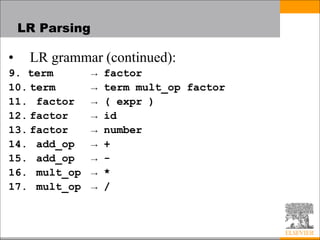

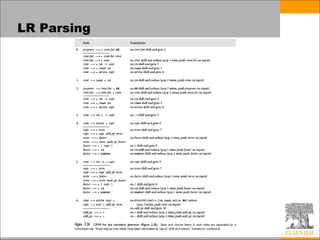

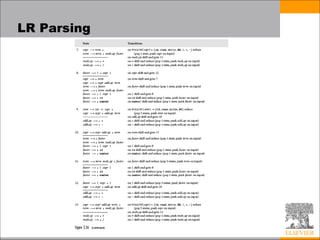

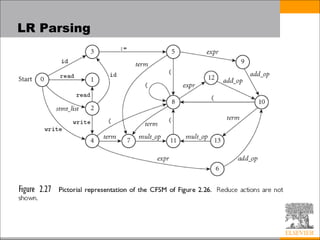

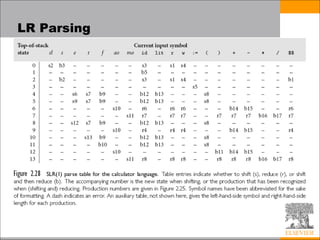

This document discusses parsing techniques for programming languages. It begins by defining regular expressions and context-free grammars. It then describes LL(1) parsing which is a top-down parsing technique that uses prediction sets to parse in linear time. The document provides an example of an LL(1) grammar and parsing table. It also discusses problems that can arise with making grammars LL(1) and techniques for resolving them. The document concludes by introducing LR parsing as a bottom-up technique that uses states and shift-reduce actions to parse in linear time.

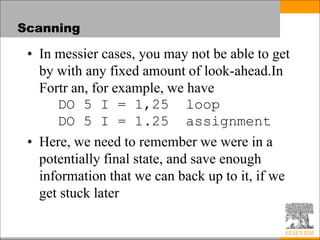

![Scanning

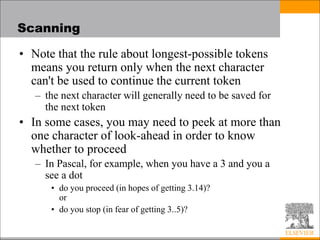

• Suppose we are building an ad-hoc (hand-

written) scanner for Pascal:

– We read the characters one at a time with look-ahead

• If it is one of the one-character tokens

{ ( ) [ ] < > , ; = + - etc }

we announce that token

• If it is a ., we look at the next character

– If that is a dot, we announce .

– Otherwise, we announce . and reuse the look-ahead](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/programminglanguagesyntax-221110063340-a264a7fb/85/Programming_Language_Syntax-ppt-12-320.jpg)