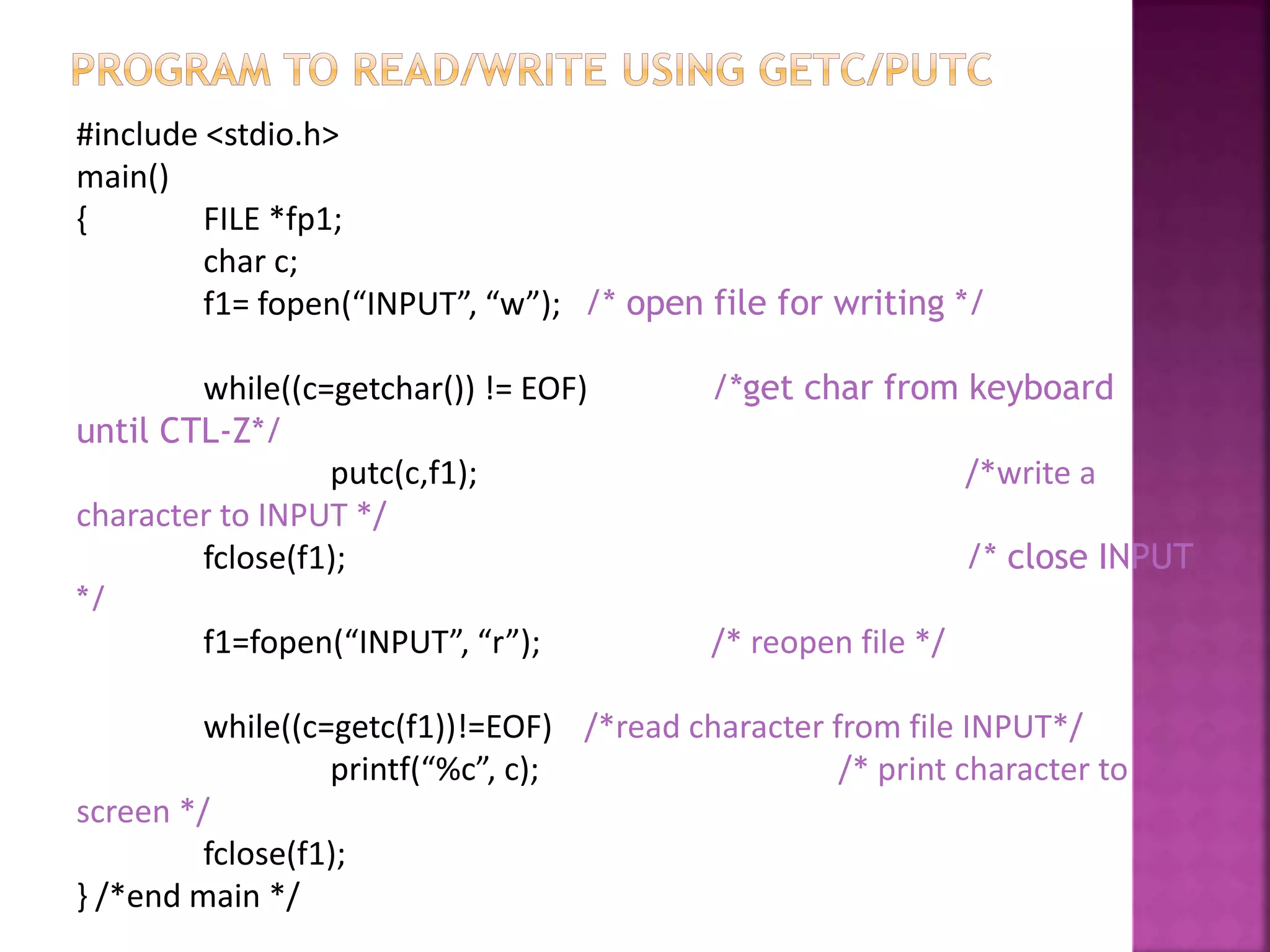

An array is a collection of variables of the same type that can be accessed using a common name. Arrays can be initialized statically at declaration or dynamically at runtime. Elements in an array are accessed using indexes and the size of an array allocates contiguous memory blocks for its elements. Structures group related data types together and allow accessing members using dot and arrow operators. Unions store different data types in the same memory location and the type of the member accessed determines the interpretation. Files provide a way to persist data in programs and functions like fopen(), fclose(), fread(), fwrite() allow opening, closing and reading/writing files. Command line arguments passed to programs can be accessed using argc and argv.

![ An Array is a collection of variables of the

same type that are referred to through a

common name.

Declaration

type var_name[size]

e.g

2

int A[6];

double d[15];](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/iiib-191030041411/75/Programming-in-C-2-2048.jpg)

![After declaration, array contains some garbage

value.

Static initialization

Run time initialization

3

int month_days[] = {31, 28, 31, 30, 31, 30, 31, 31, 30, 31, 30, 31};

int i;

int A[6];

for(i = 0; i < 6; i++)

A[i] = 6 - i;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/iiib-191030041411/75/Programming-in-C-3-2048.jpg)

![int A[6];

6 elements of 4 bytes each,

total size = 6 x 4 bytes = 24 bytes

Read an element

Write to an element

{program: array_average.c}

4

A[0] A[1] A[2] A[3] A[4] A[5]

0x1000 0x1004 0x1008 0x1012 0x1016 0x1020

6 5 4 3 2 1

int tmp = A[2];

A[3] = 5;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/iiib-191030041411/75/Programming-in-C-4-2048.jpg)

![ No “Strings” keyword

A string is an array of characters.

OR

5

char string[] = “hello world”;

char *string = “hello world”;](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/iiib-191030041411/75/Programming-in-C-5-2048.jpg)

![• Compiler has to know where the string ends

• ‘0’ denotes the end of string

{program: hello.c}

Some more characters (do $man ascii):

‘n’ = new line, ‘t’ = horizontal tab, ‘v’ =

vertical tab, ‘r’ = carriage return

‘A’ = 0x41, ‘a’ = 0x61, ‘0’ = 0x00

6

char string[] = “hello world”;

printf(“%s”, string);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/iiib-191030041411/75/Programming-in-C-6-2048.jpg)

![ Direct access operator s.m

subscript and dot operators have same precedence and

associate left-to-right, so we don’t need parentheses for

sam.pets[0].species

Indirect access s->m: equivalent to (*s).m

Dereference a pointer to a structure, then return a

member of that structure

Dot operator has higher precedence than indirection

operator , so parentheses are needed in (*s).m

(*fido.owner).name or fido.owner->name

10

. evaluated first: access owner member

* evaluated next: dereference pointer to

HUMAN

. and -> have equal precedence

and associate left-to-right](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/iiib-191030041411/75/Programming-in-C-10-2048.jpg)

![ can give input to C program from command line

E.g. > prog.c 10

name1 name2 ….

how to use these arguments?

main ( int argc, char *argv[] )

argc – gives a count of number of arguments

(including program name)

char *argv[] defines an array of pointers to

character (or array of strings)

argv[0] – program name

argv[1] to argv[argc -1] give the other arguments

as strings](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/iiib-191030041411/75/Programming-in-C-30-2048.jpg)