The document outlines various financial and accounting scenarios related to borrowing and amortization for two companies, Norwood and Gordon Enterprises, including their installment payments, accrued interest, and amortization tables. It also compares debt to equity ratios of Pulaski and Scott Companies, as well as Atlas and Bryan Companies, highlighting the associated risks of high debt levels. Additionally, the text delves into the historical context and implications of policing in the era of homeland security post-September 11, 2001.

![were busy at duties such as getting medical supplies while Ong

and Sweeney were re-

porting the events.

At 8:41, in America’s operations center, a colleague told

Marquis that the air traffic

controllers declared Flight 11 a hijacking and “think he’s

[American 11] headed toward

Kennedy [airport in New York City]. They’re moving everybody

out of the way. They

seem to have him on a primary radar. They seem to think that he

is descending.”

At 8:44, Gonzalez reported losing phone contact with Ong.

About this same time

Sweeney reported to Woodward, “Something is wrong. We are

in a rapid descent . . . we

are all over the place.” Woodward asked Sweeney to look out

the window to see if she

could determine where they were. Sweeney responded: “We are

flying low. We are fly-

ing very, very low. We are flying way too low.” Seconds later

she said, “Oh my God we are

way too low.” The phone call ended.

At 8:46:40, American 11 crashed into the North Tower of the

World Trade Center in

New York City. All on board, along with an unknown number of

people in the tower, were

killed instantly.

The Hijacking of United 175

United Airlines Flight 175 was scheduled to depart for Los

Angeles at 8:00. Captain Victor

Saracini and First Officer Michael Horrocks piloted the Boeing

767, which had seven](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/problem14-6aproblem14-6anorwoodsborrowings1-221119031245-d49f3303/75/PROBLEM-14-6AProblem-14-6A-Norwoods-Borrowings1-Total-amount-of-docx-63-2048.jpg)

![Recovery effort from the attack on the Pentagon, Arlington

County, Virginia. (Source: Photo Courtesy of

the Federal Emergency Management Agency [FEMA].)

IS

B

N

0

-5

5

8

-3

7

2

7

5

-9

Homeland Security for Policing, by Willard M. Oliver.

Published by Prentice Hall. Copyright © 2007 by Pearson

Education, Inc.

UNDERSTANDING THE RESPONSE 55

BOX 1-10

TERRORISM TIME LINE (ABBREVIATED)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/problem14-6aproblem14-6anorwoodsborrowings1-221119031245-d49f3303/75/PROBLEM-14-6AProblem-14-6A-Norwoods-Borrowings1-Total-amount-of-docx-167-2048.jpg)

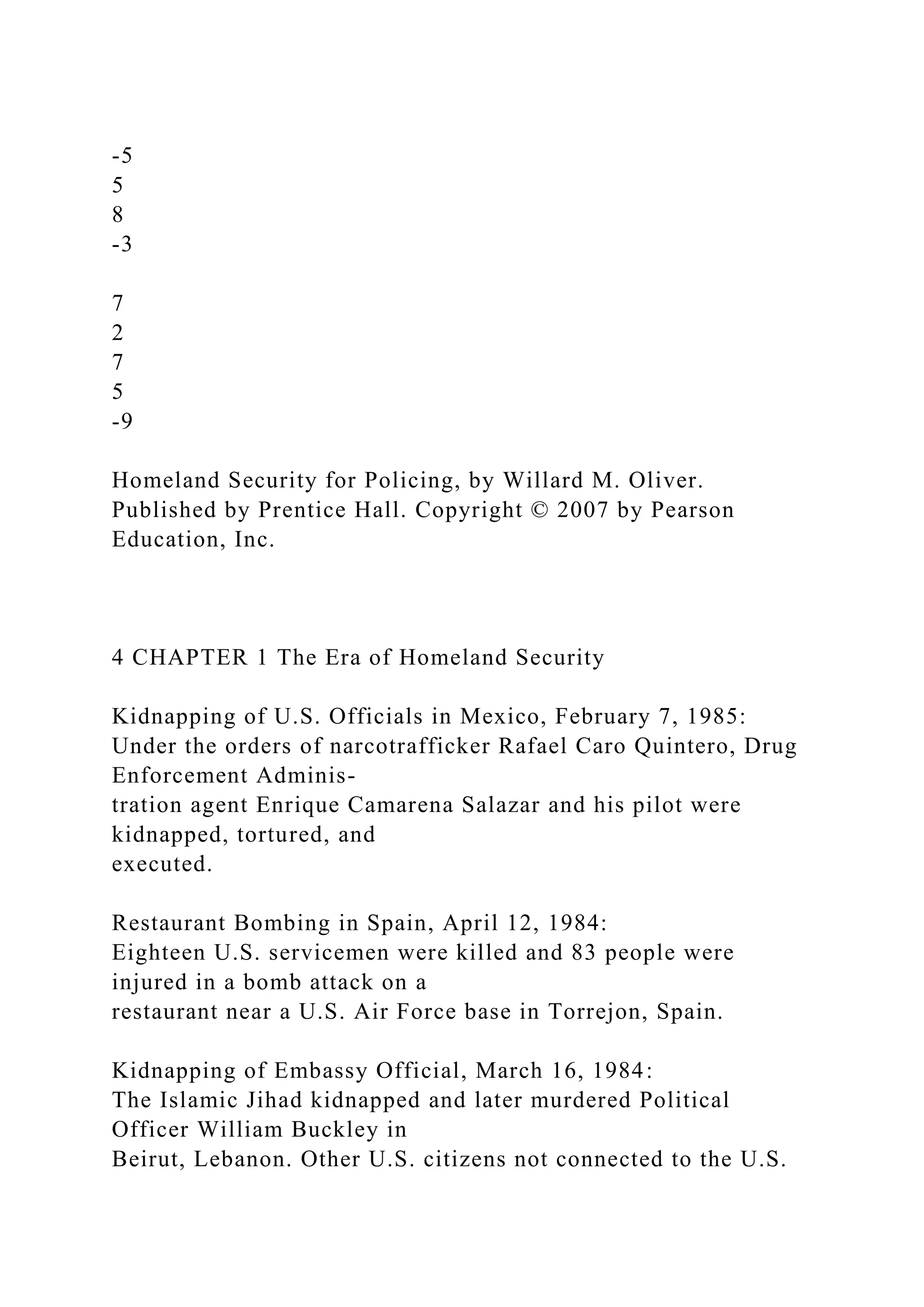

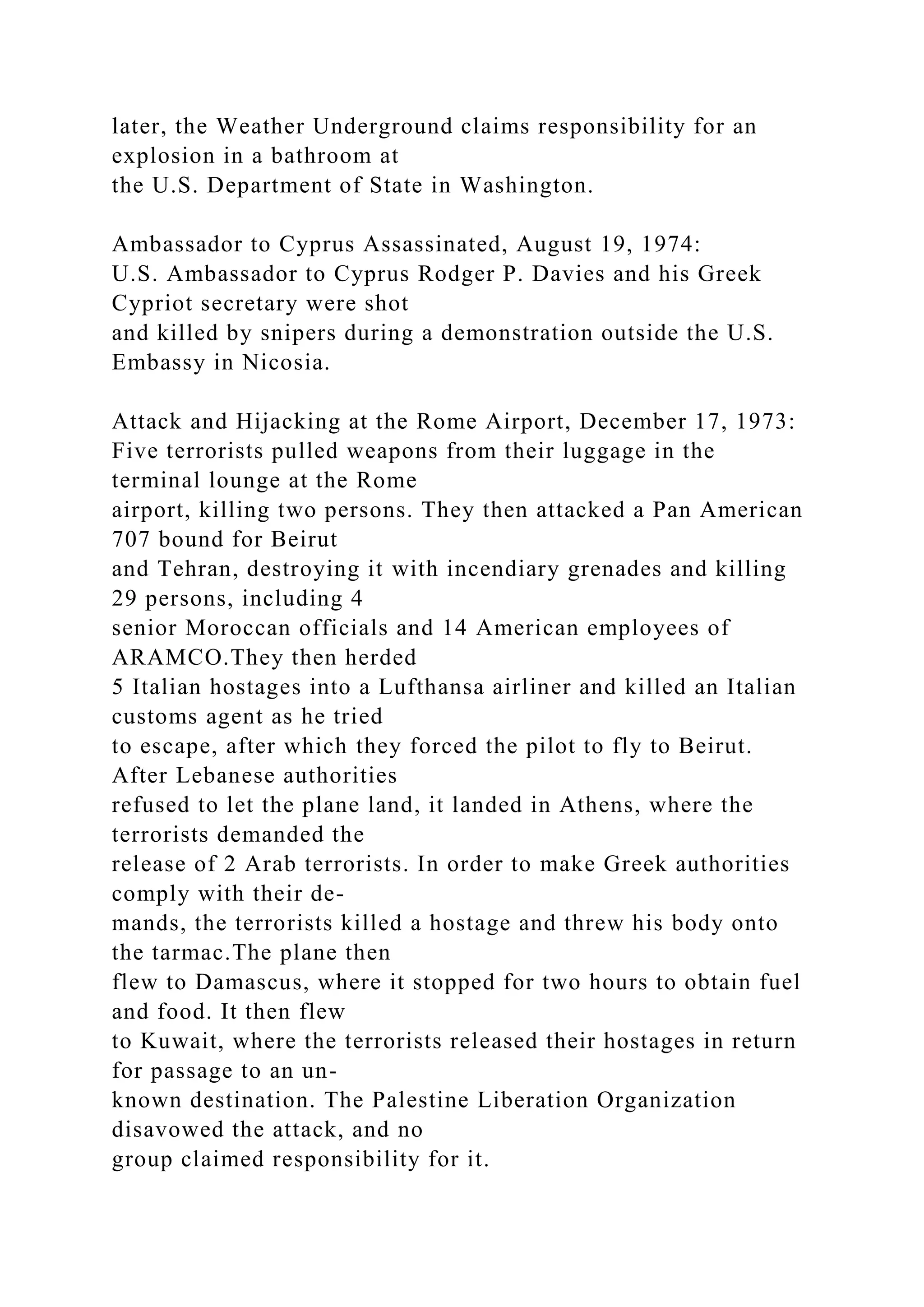

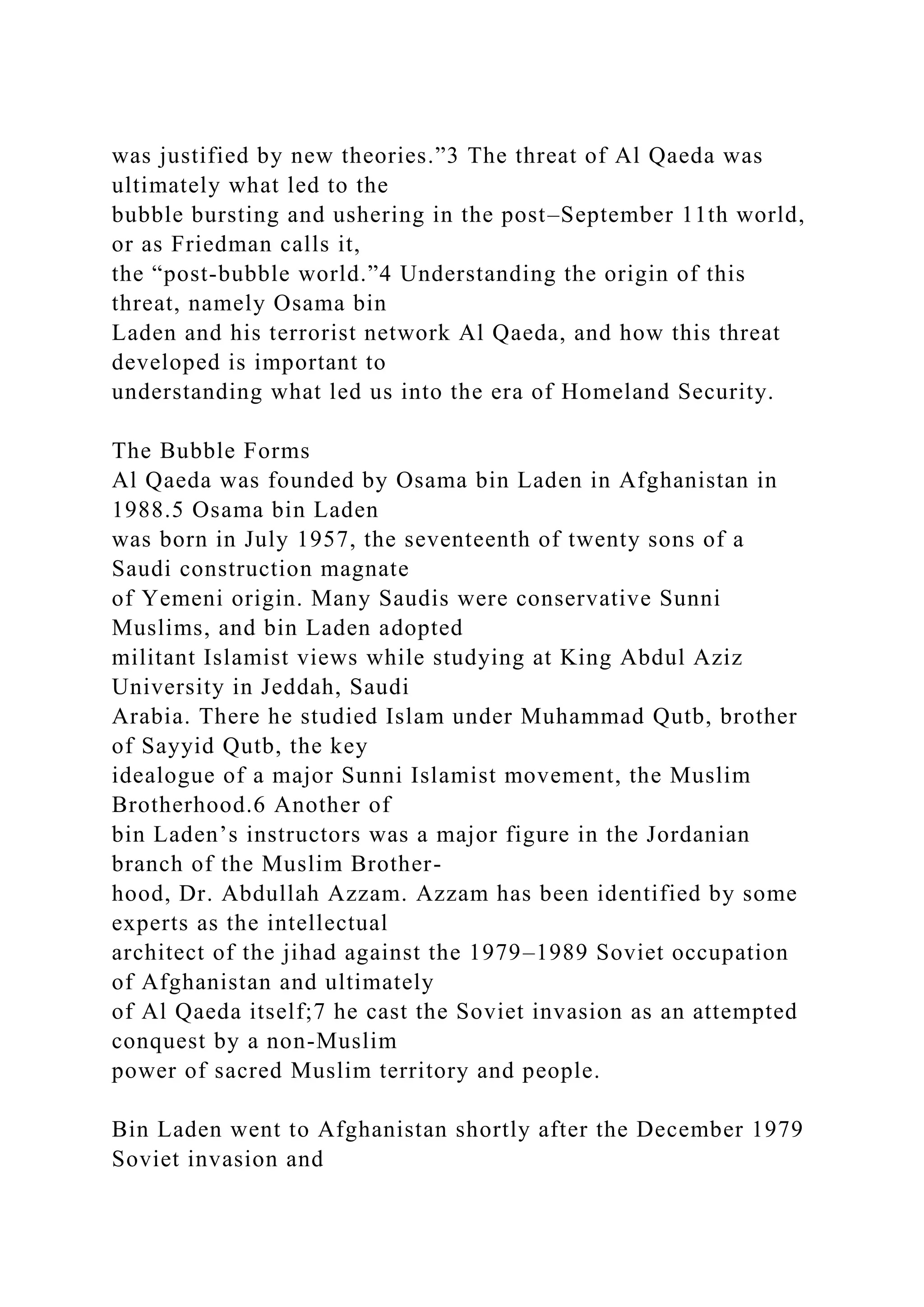

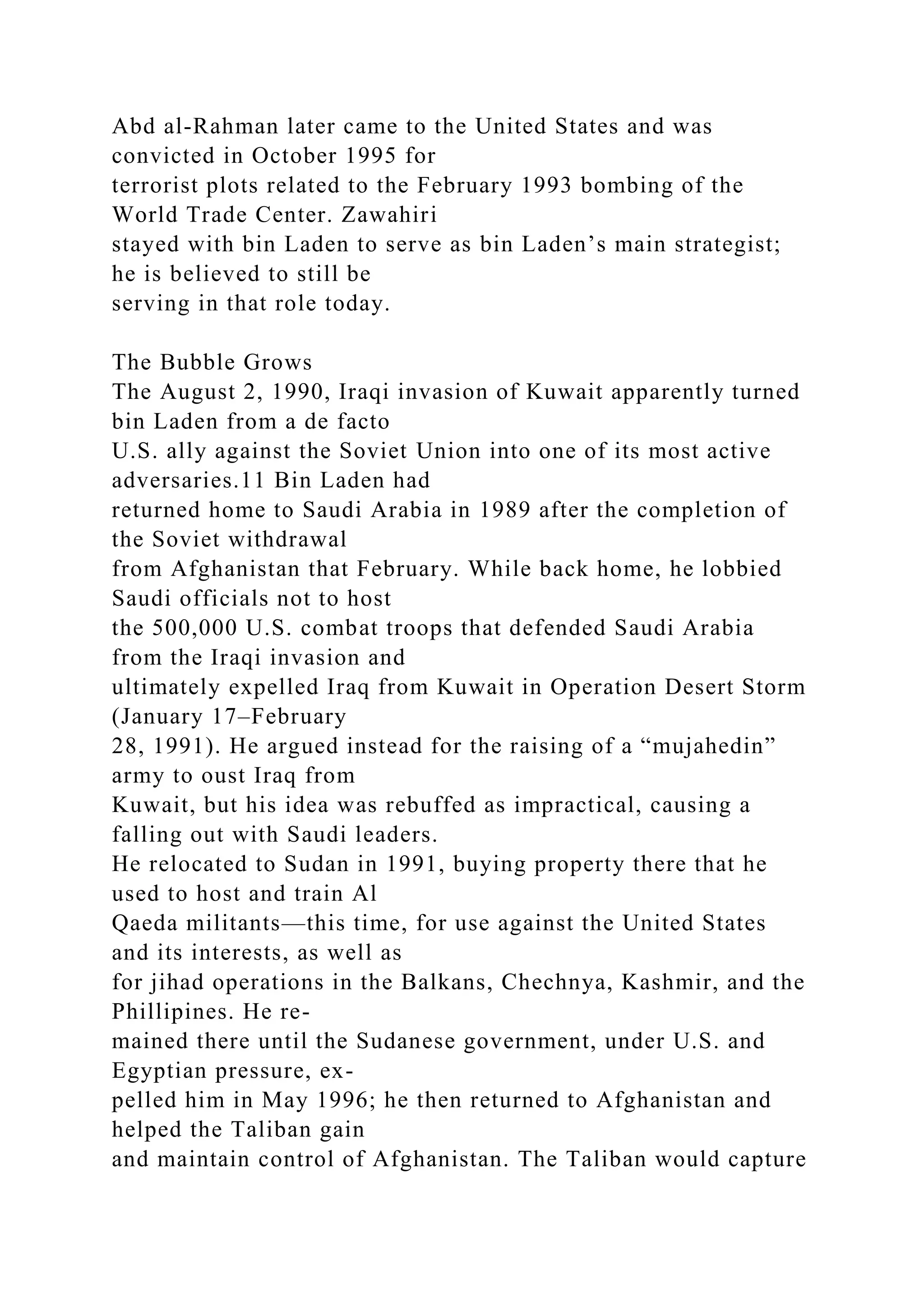

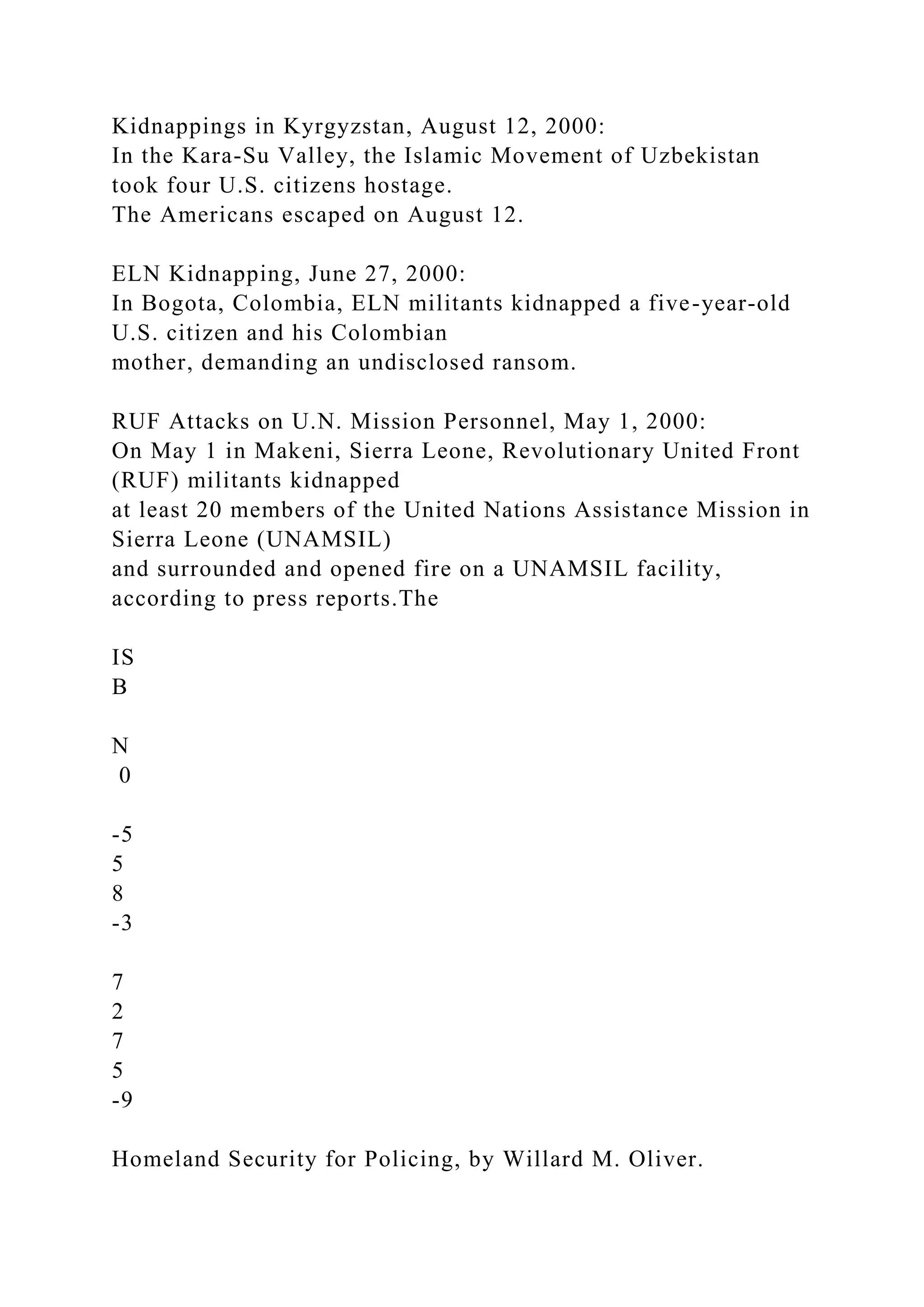

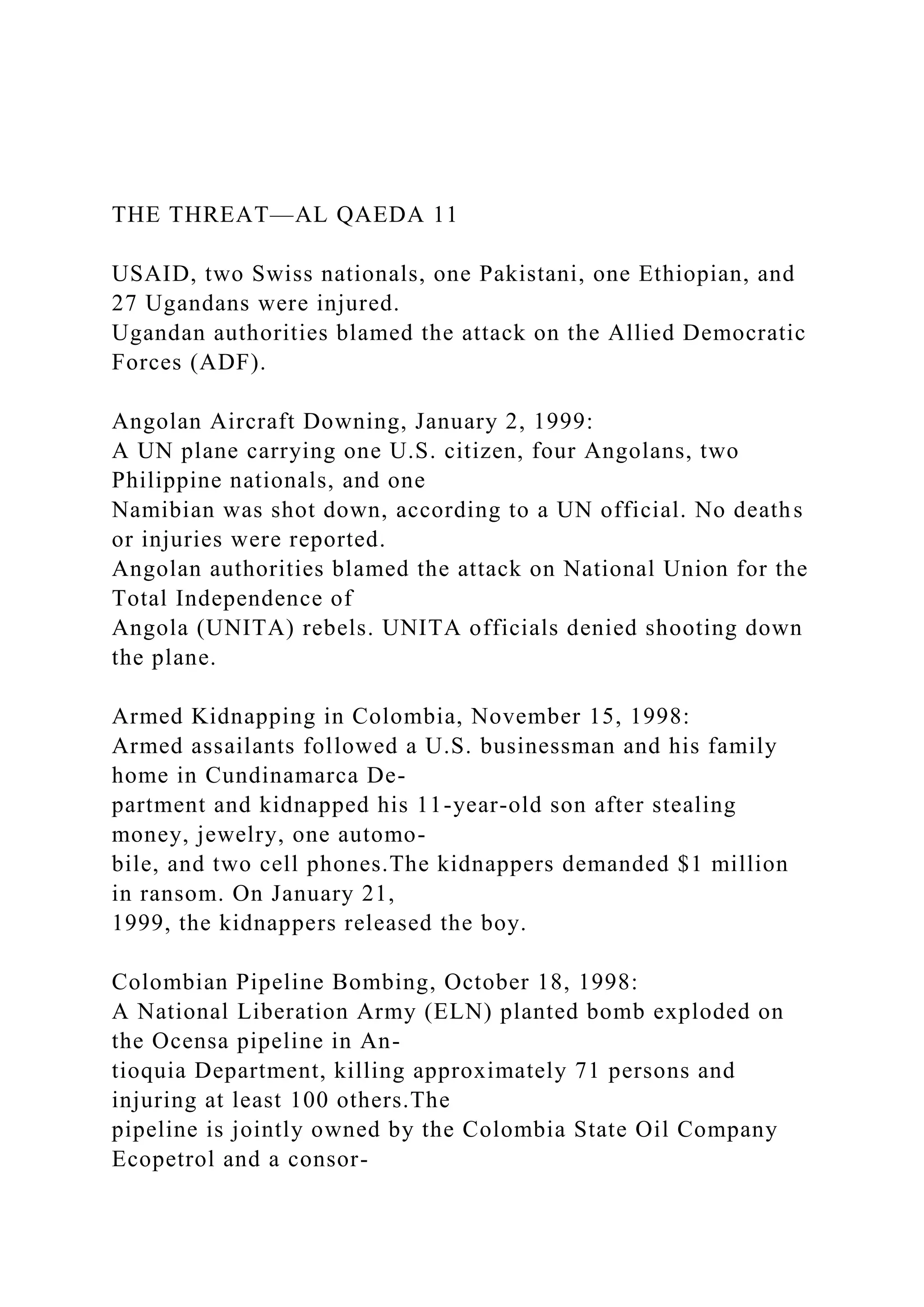

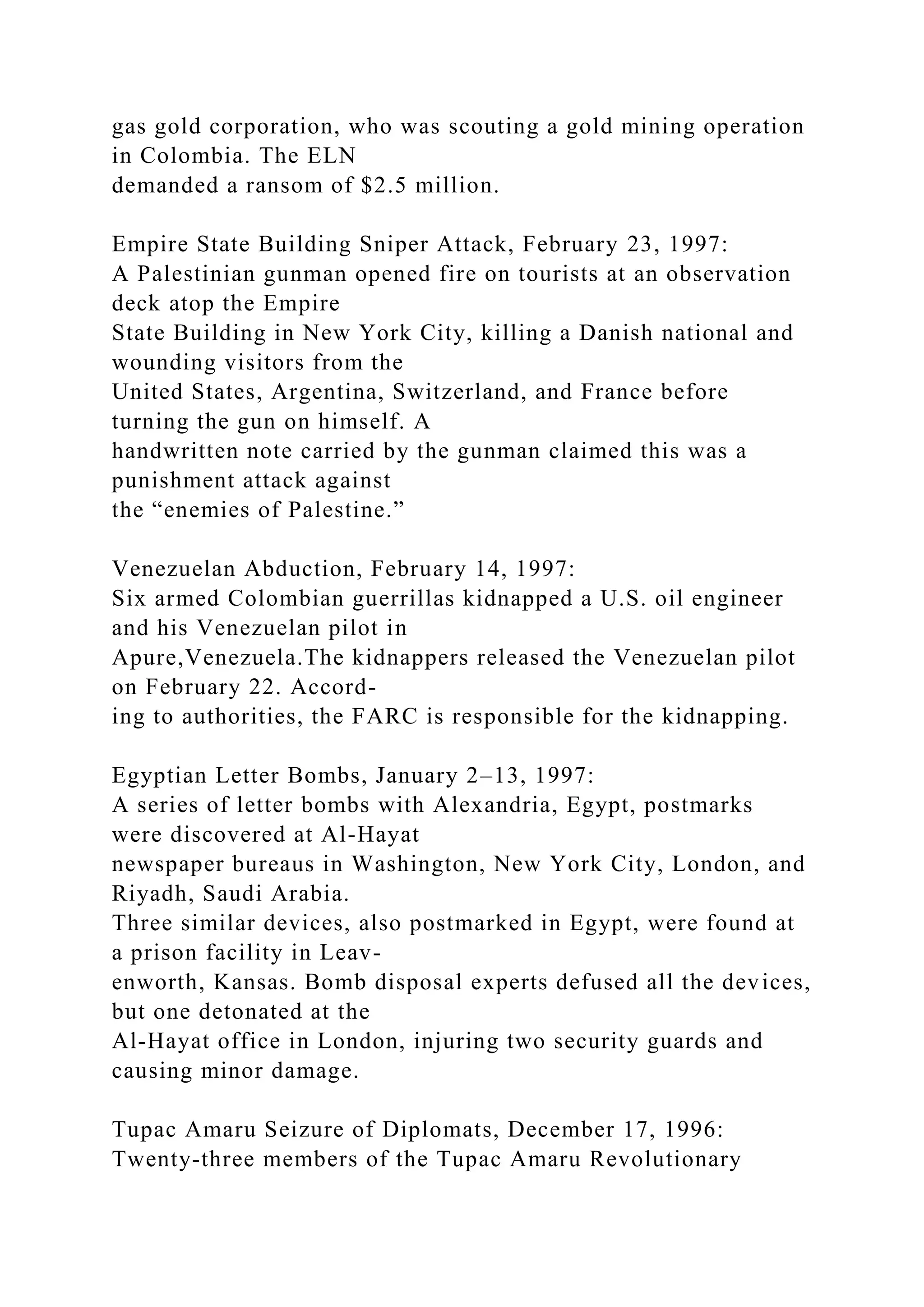

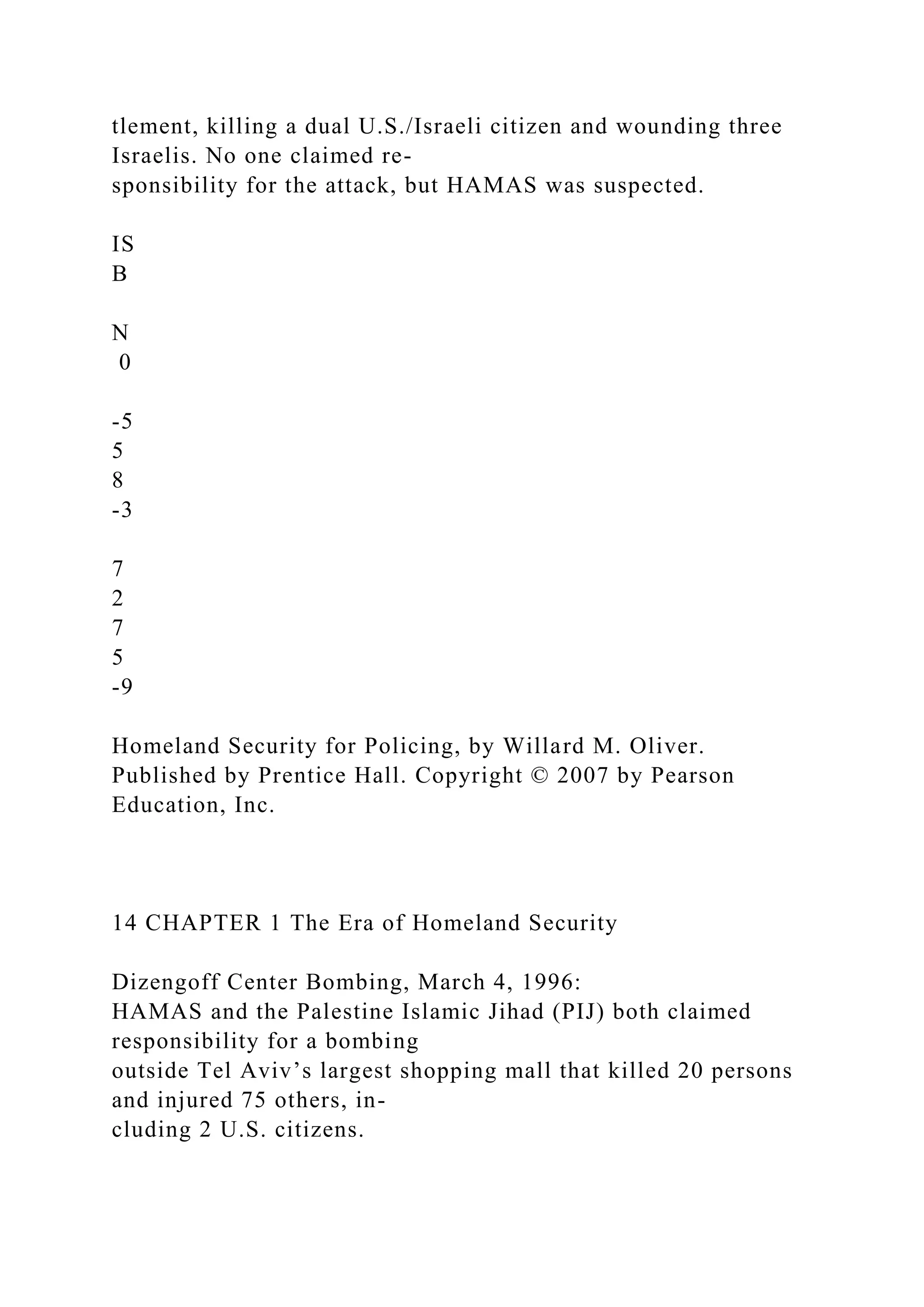

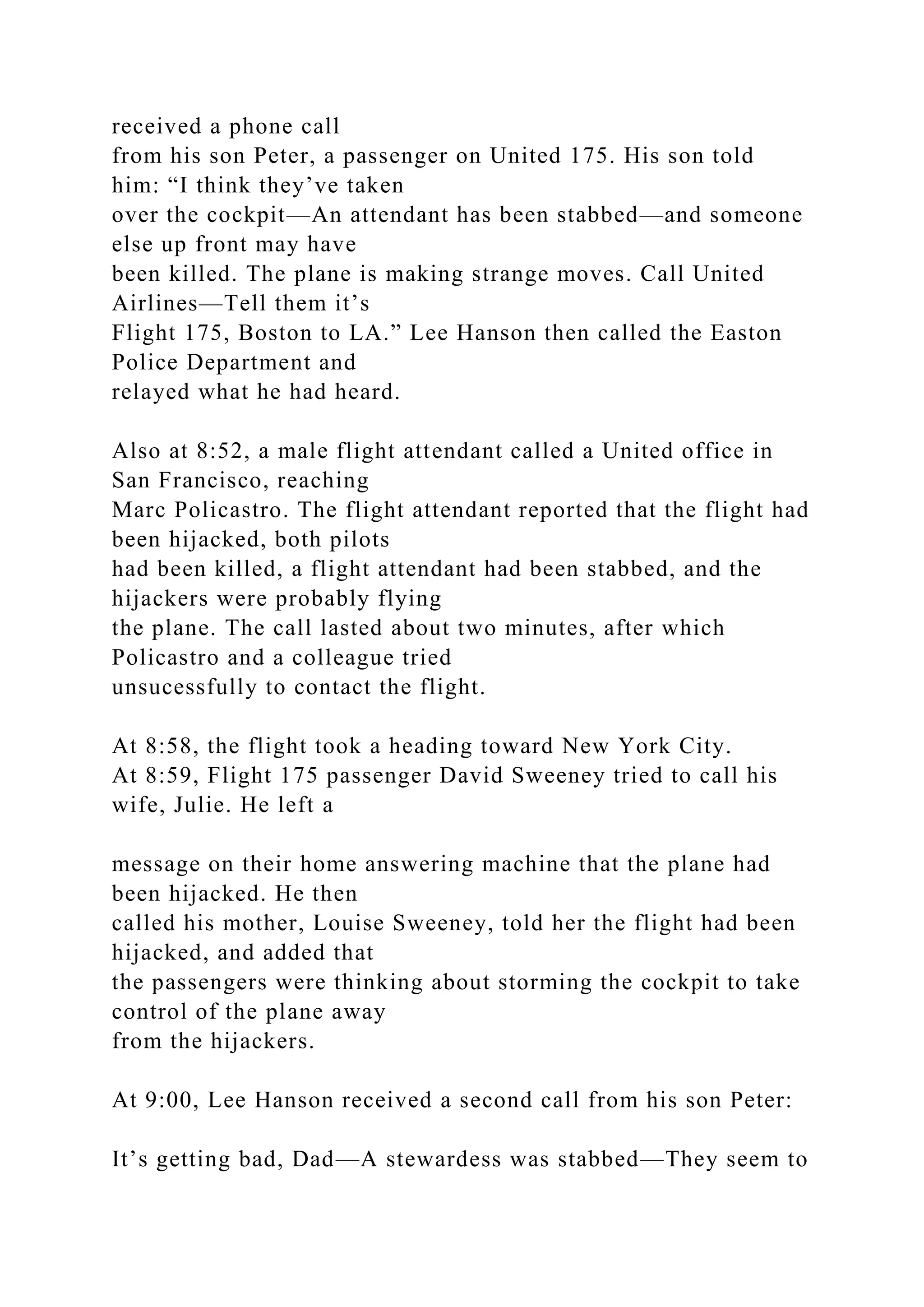

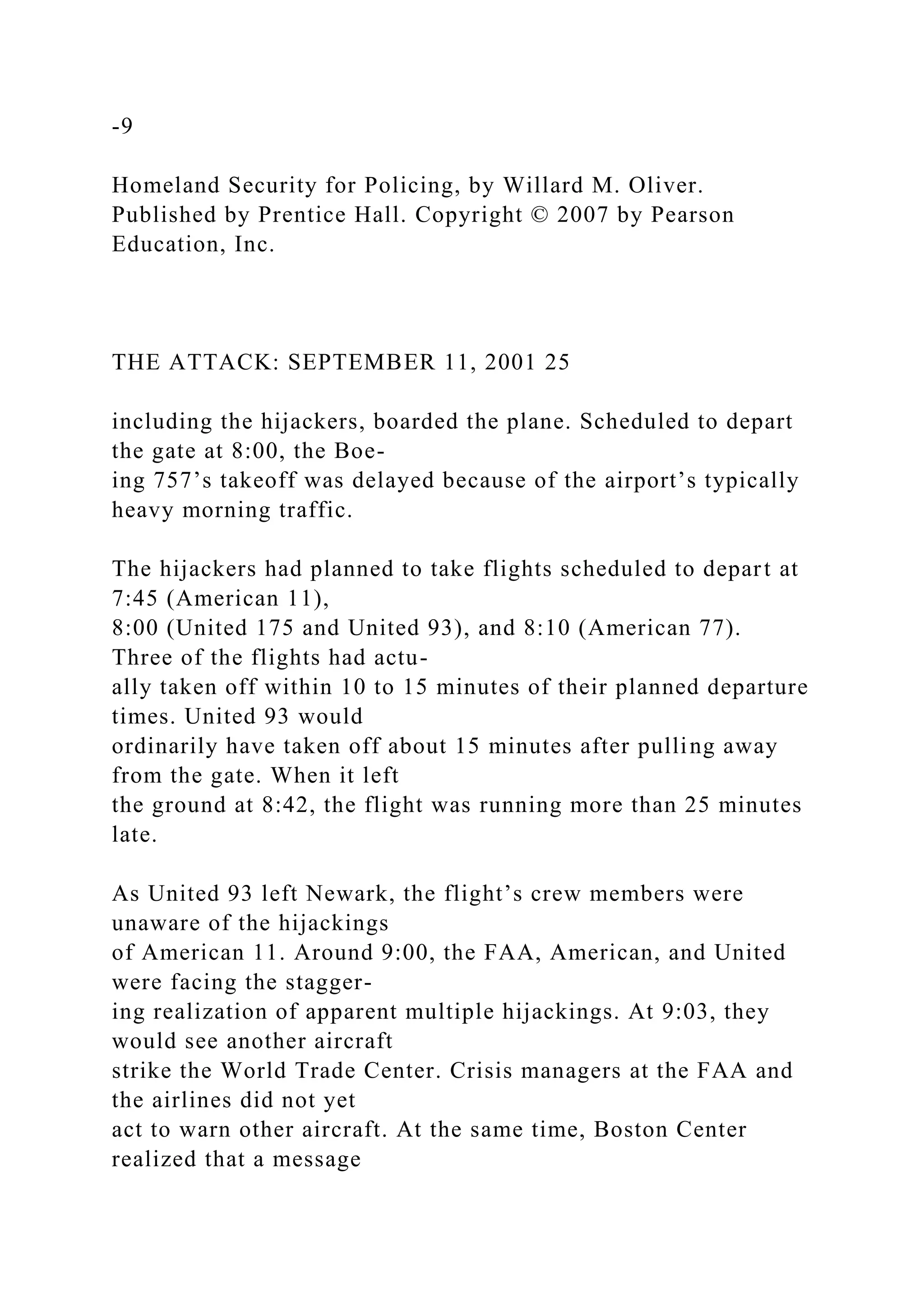

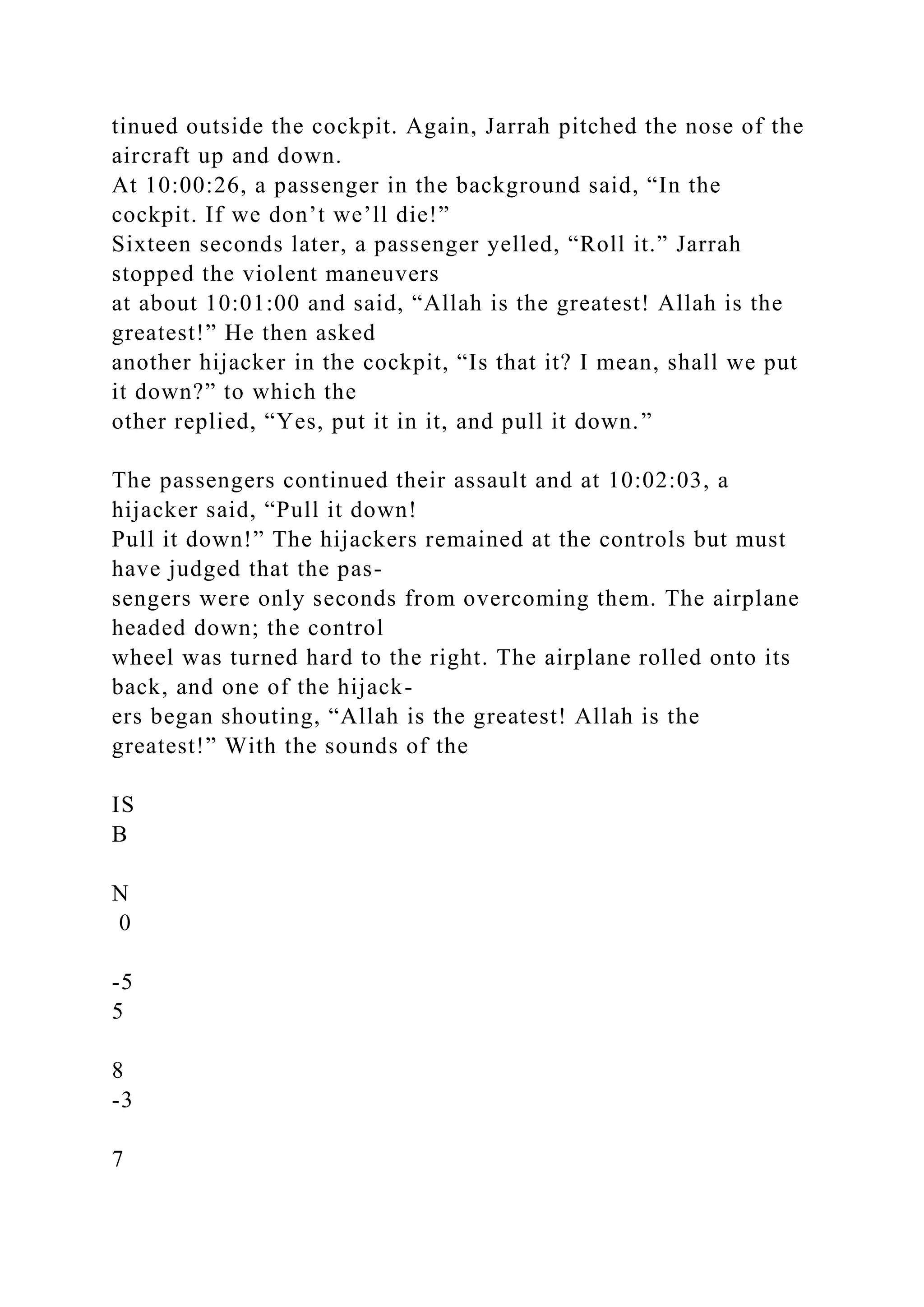

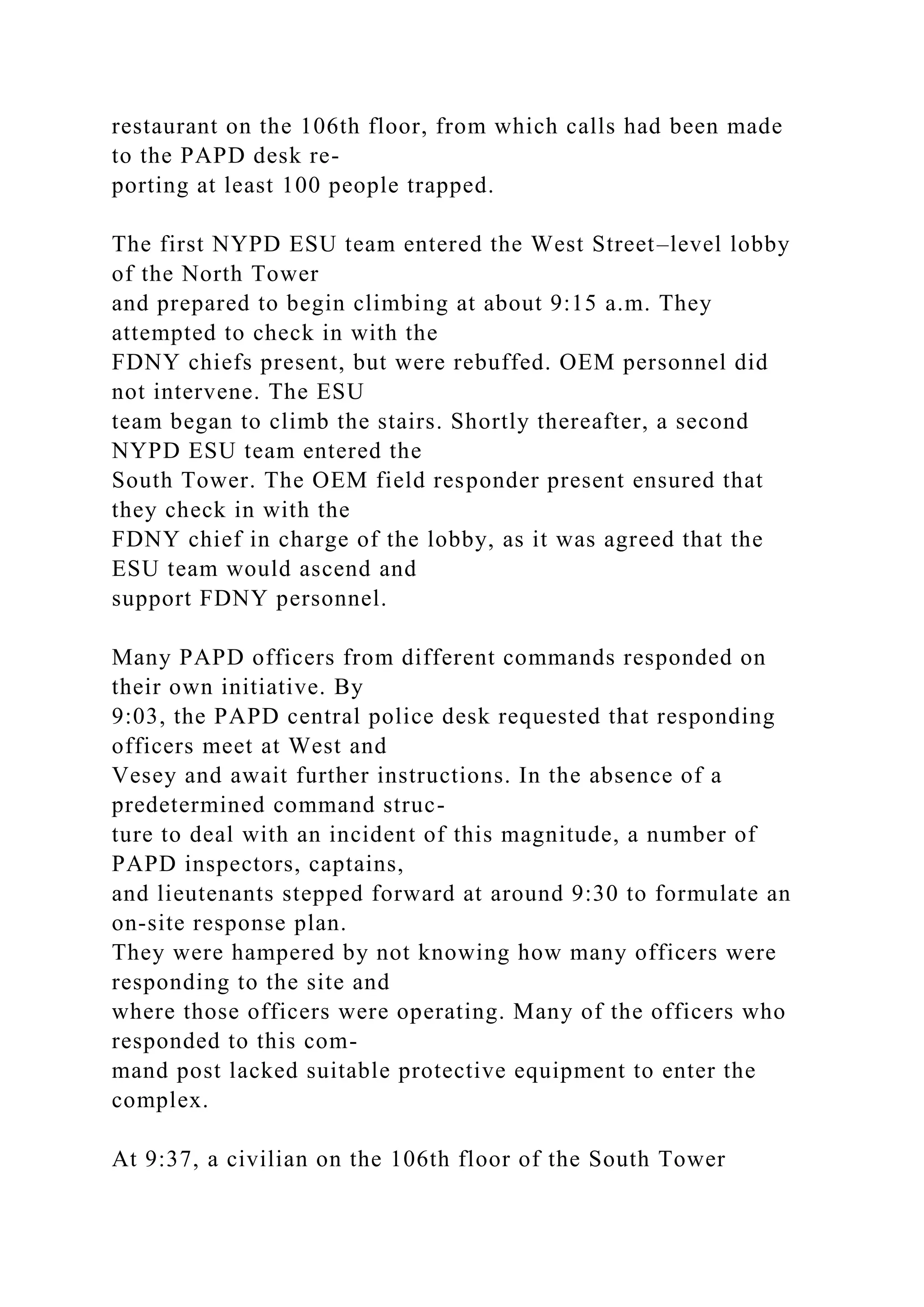

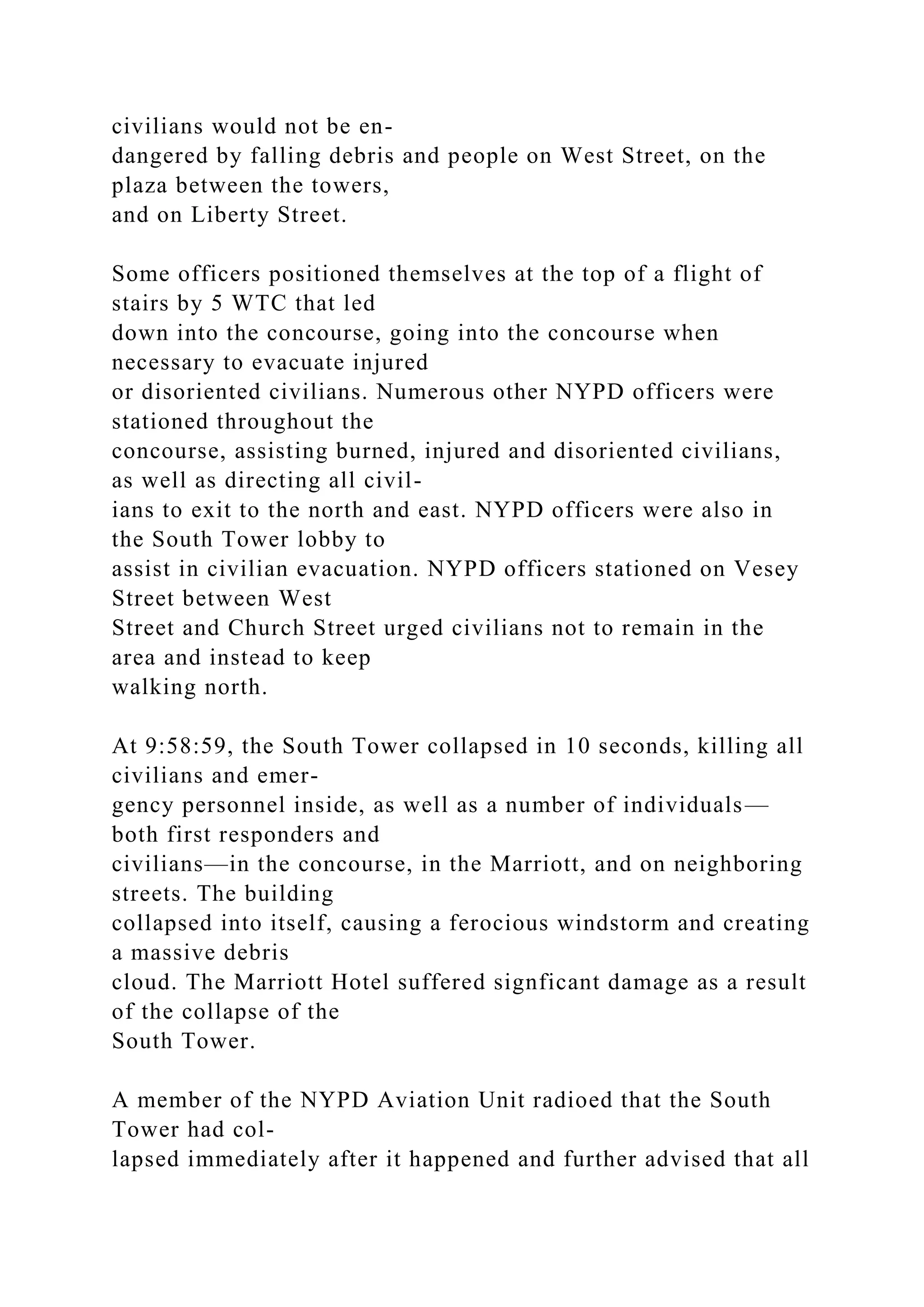

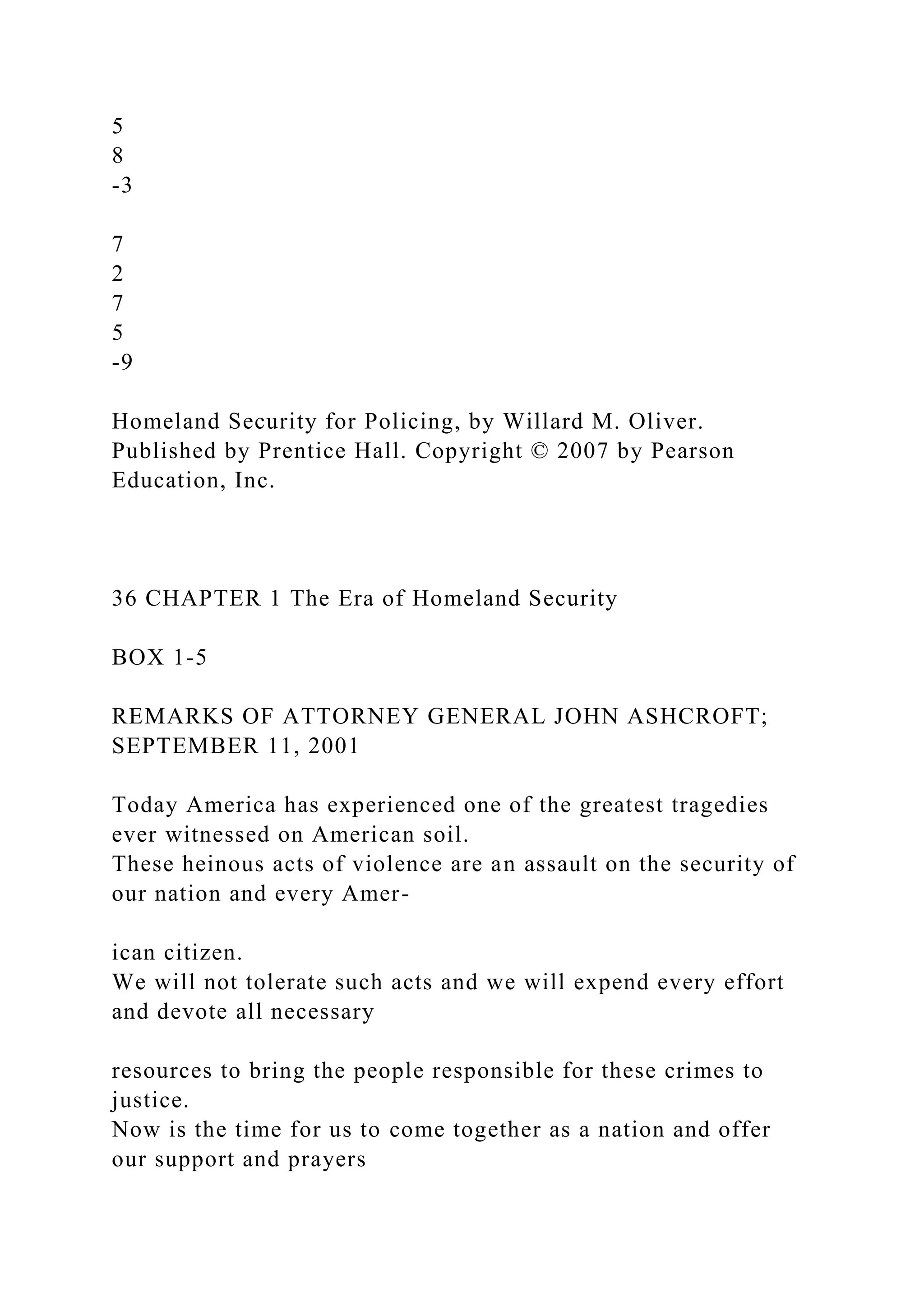

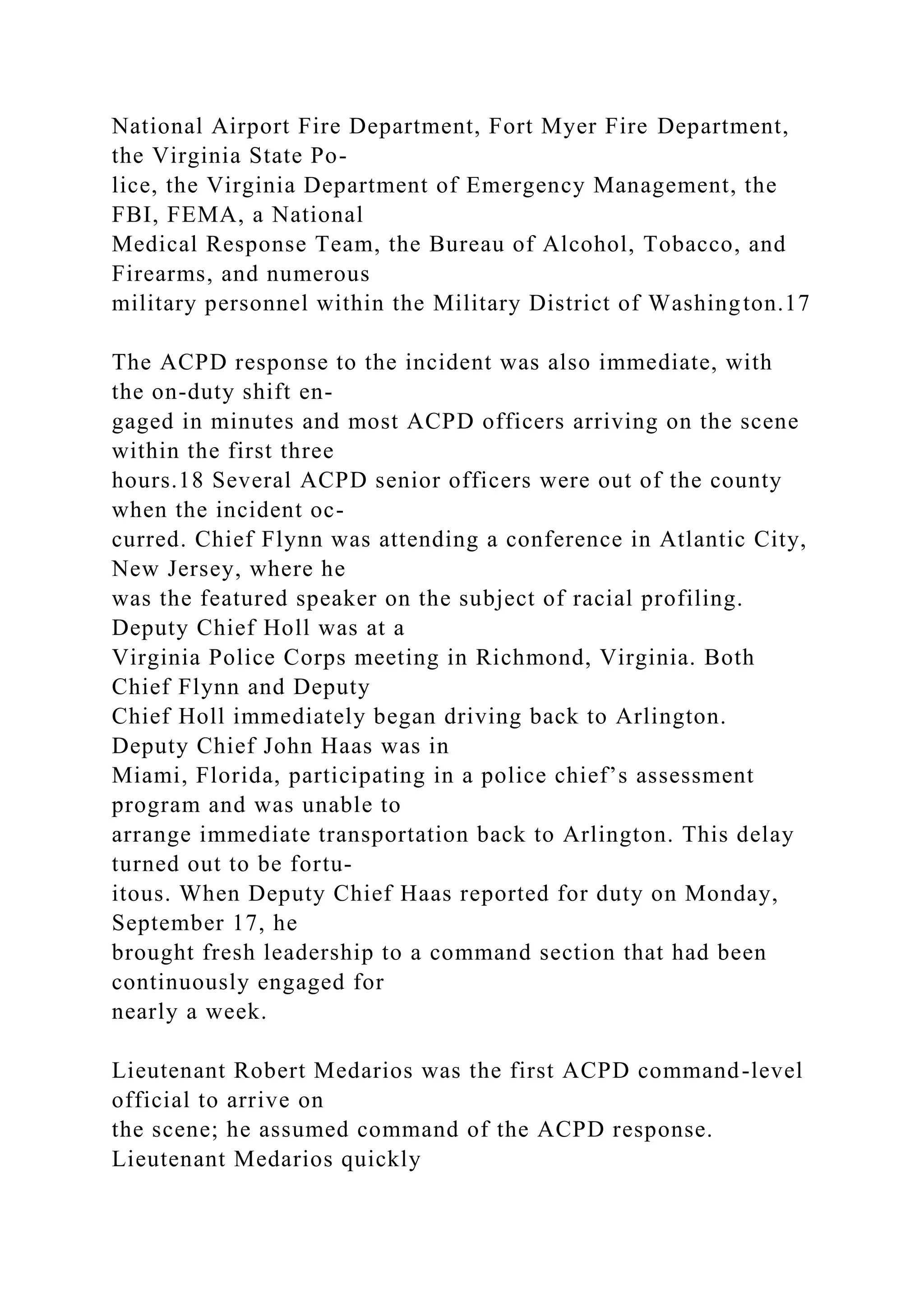

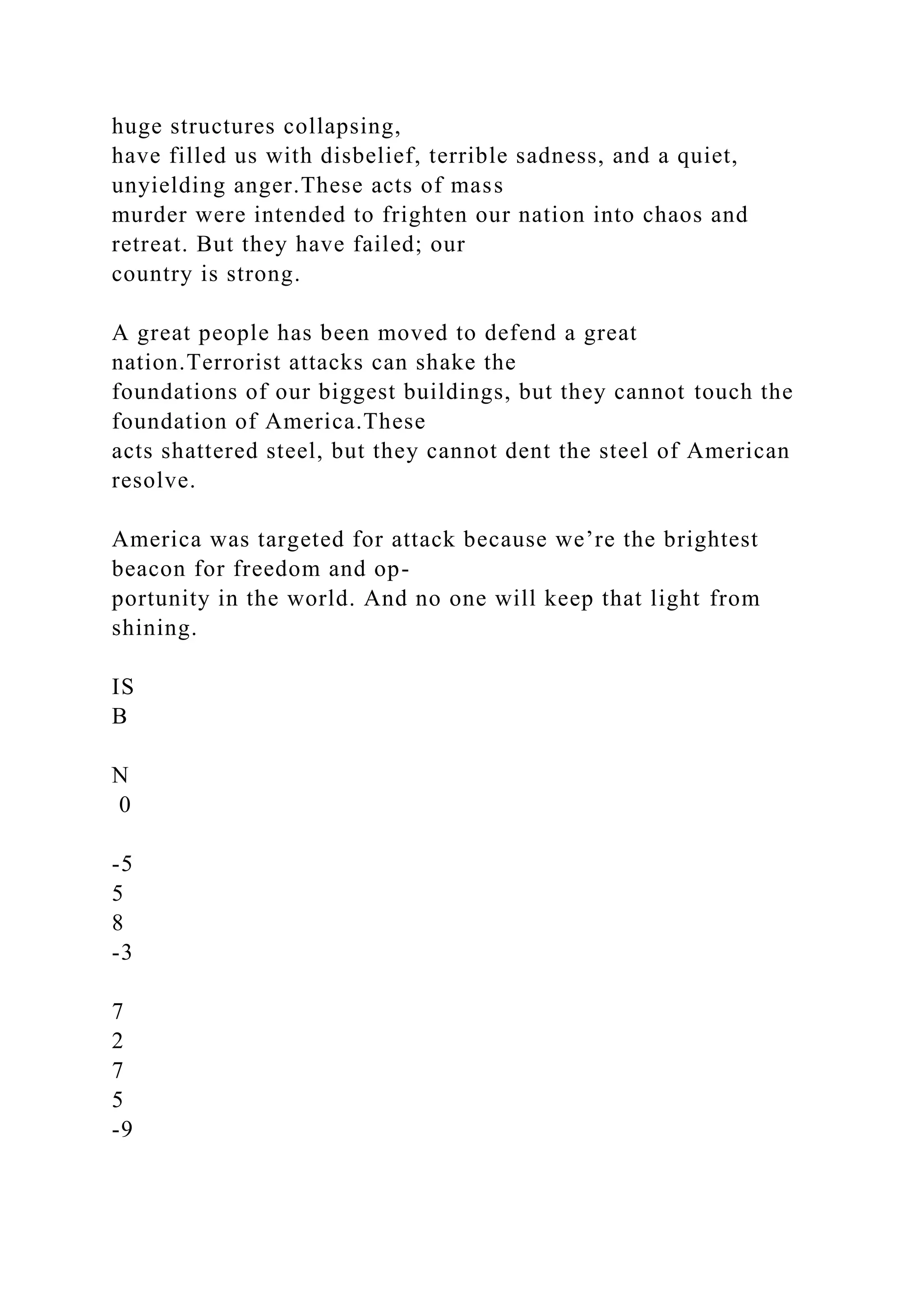

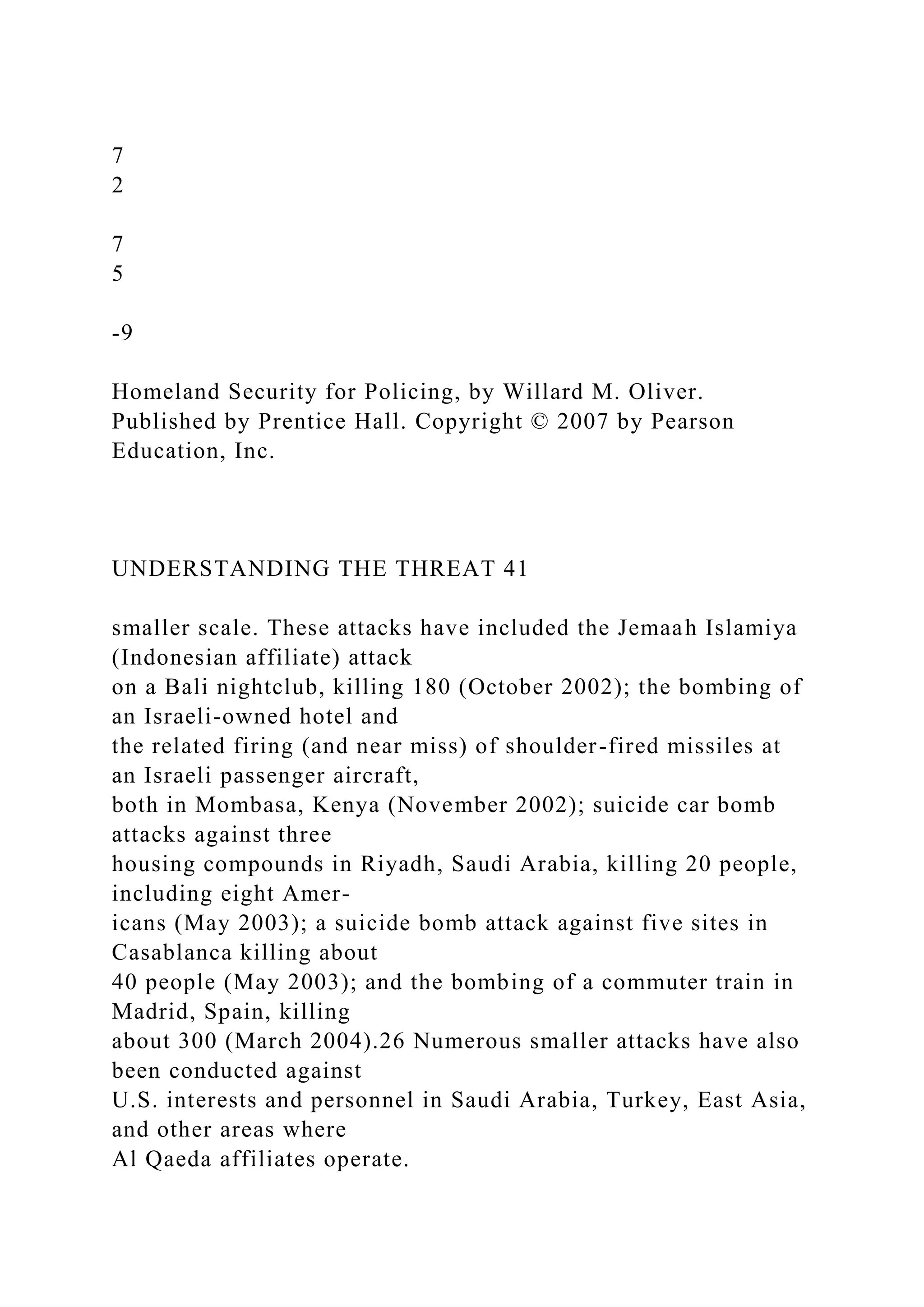

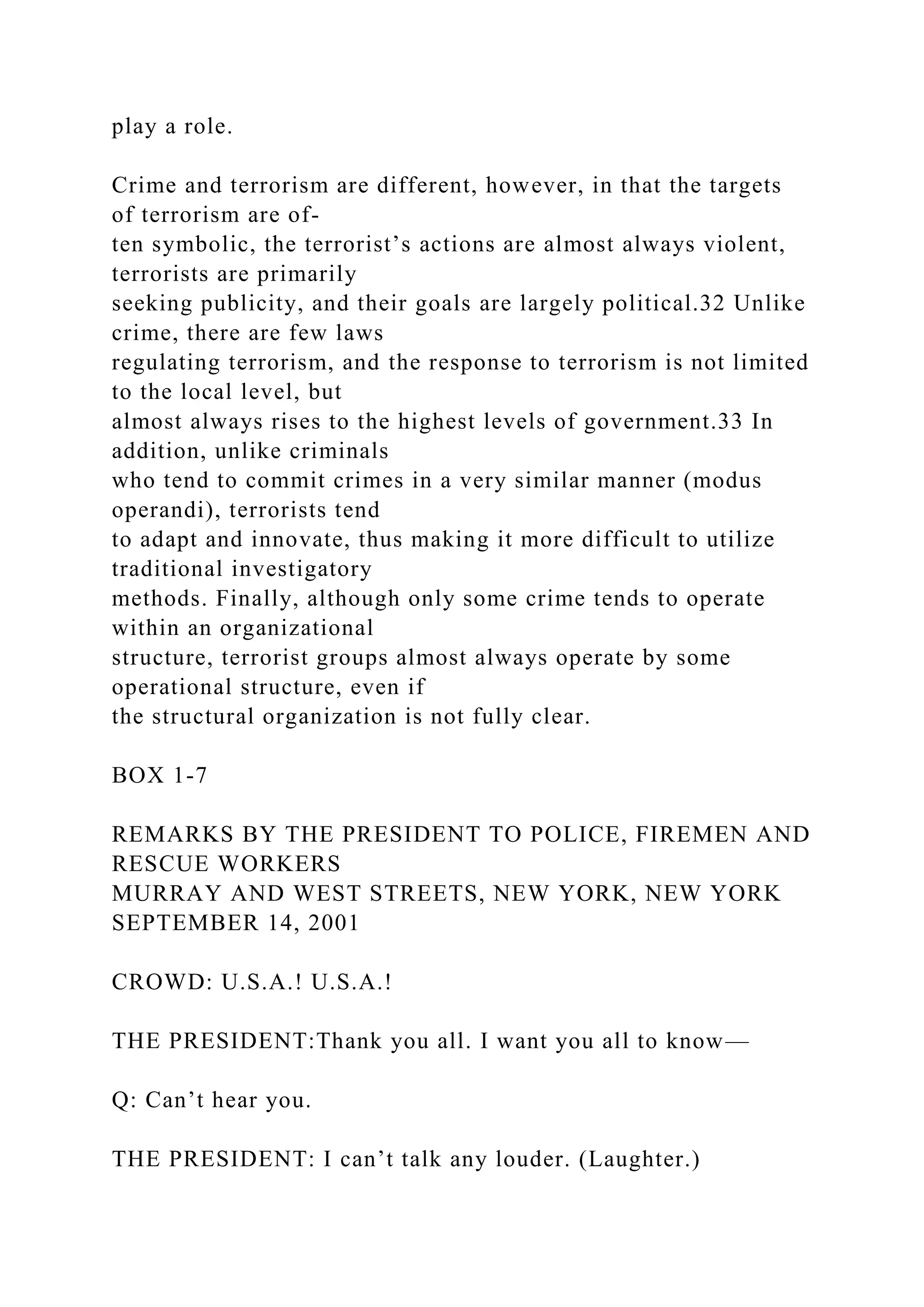

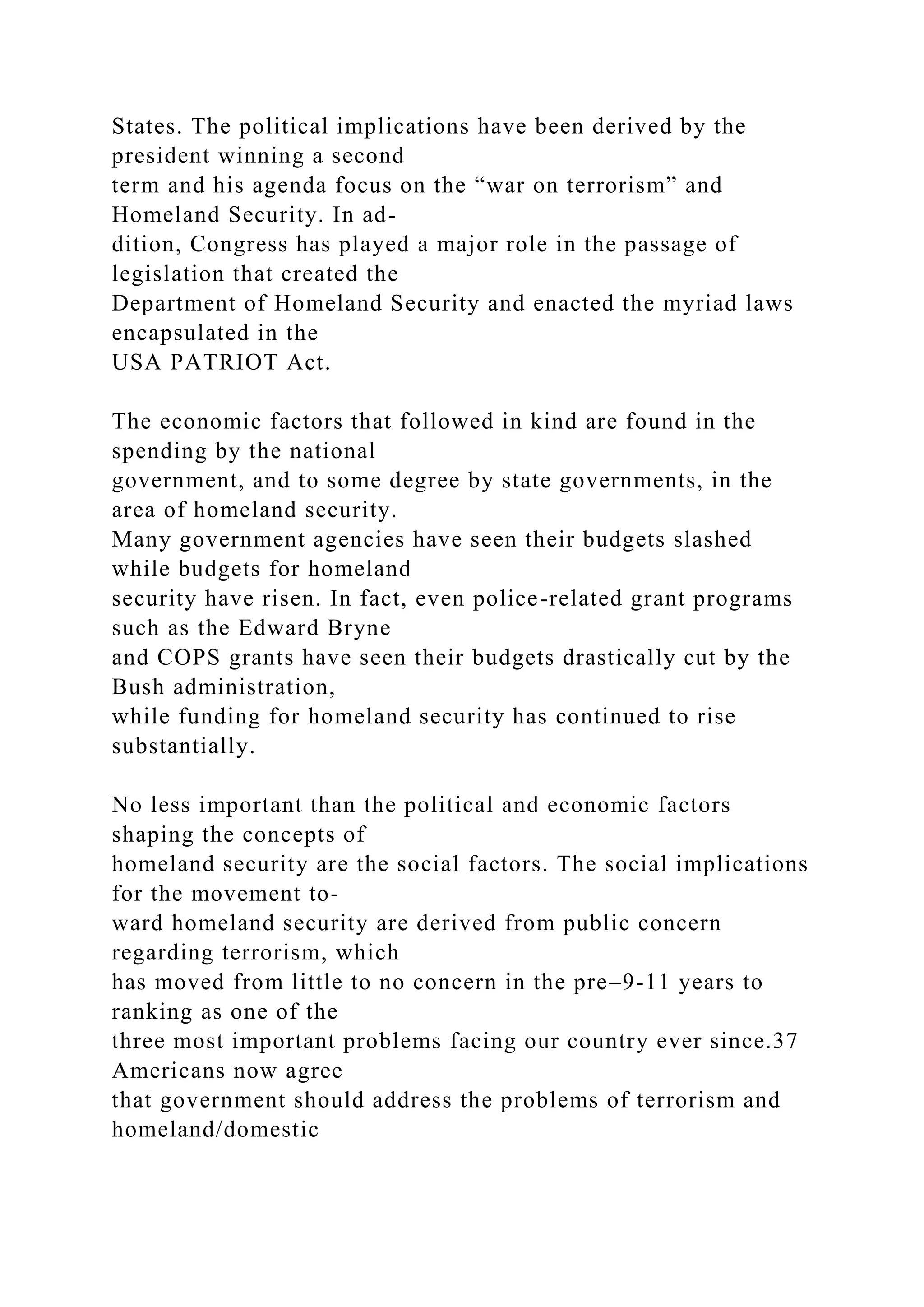

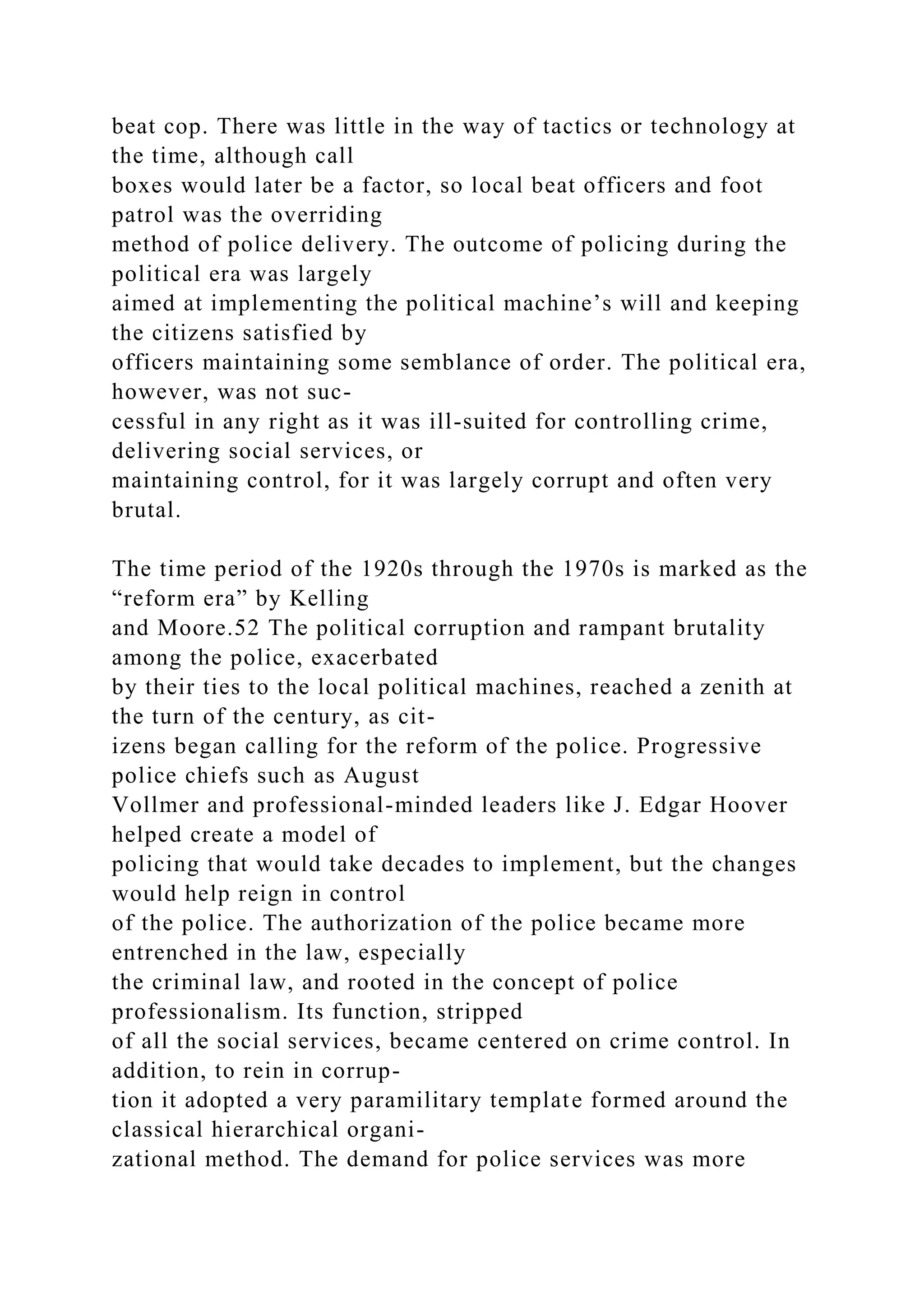

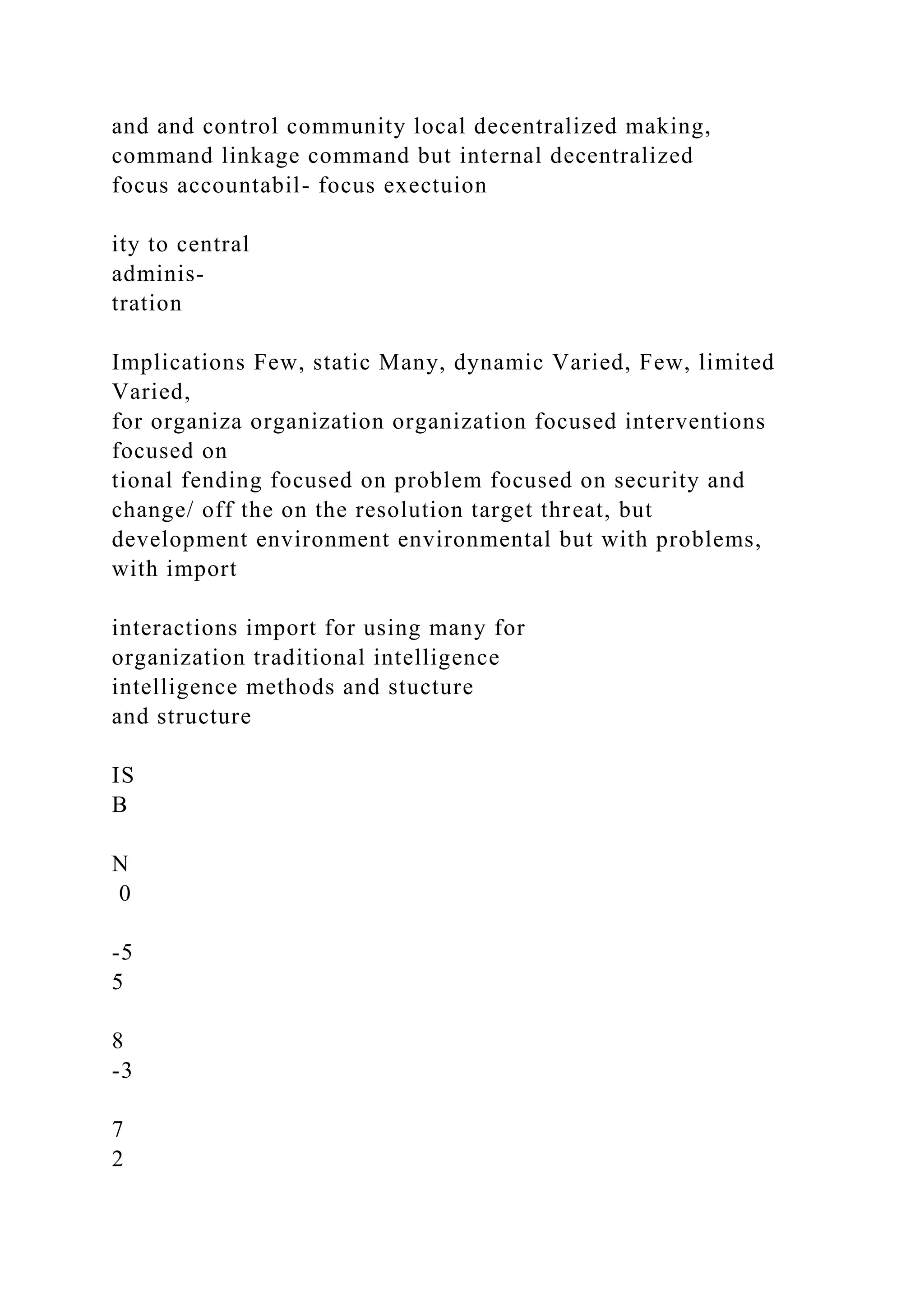

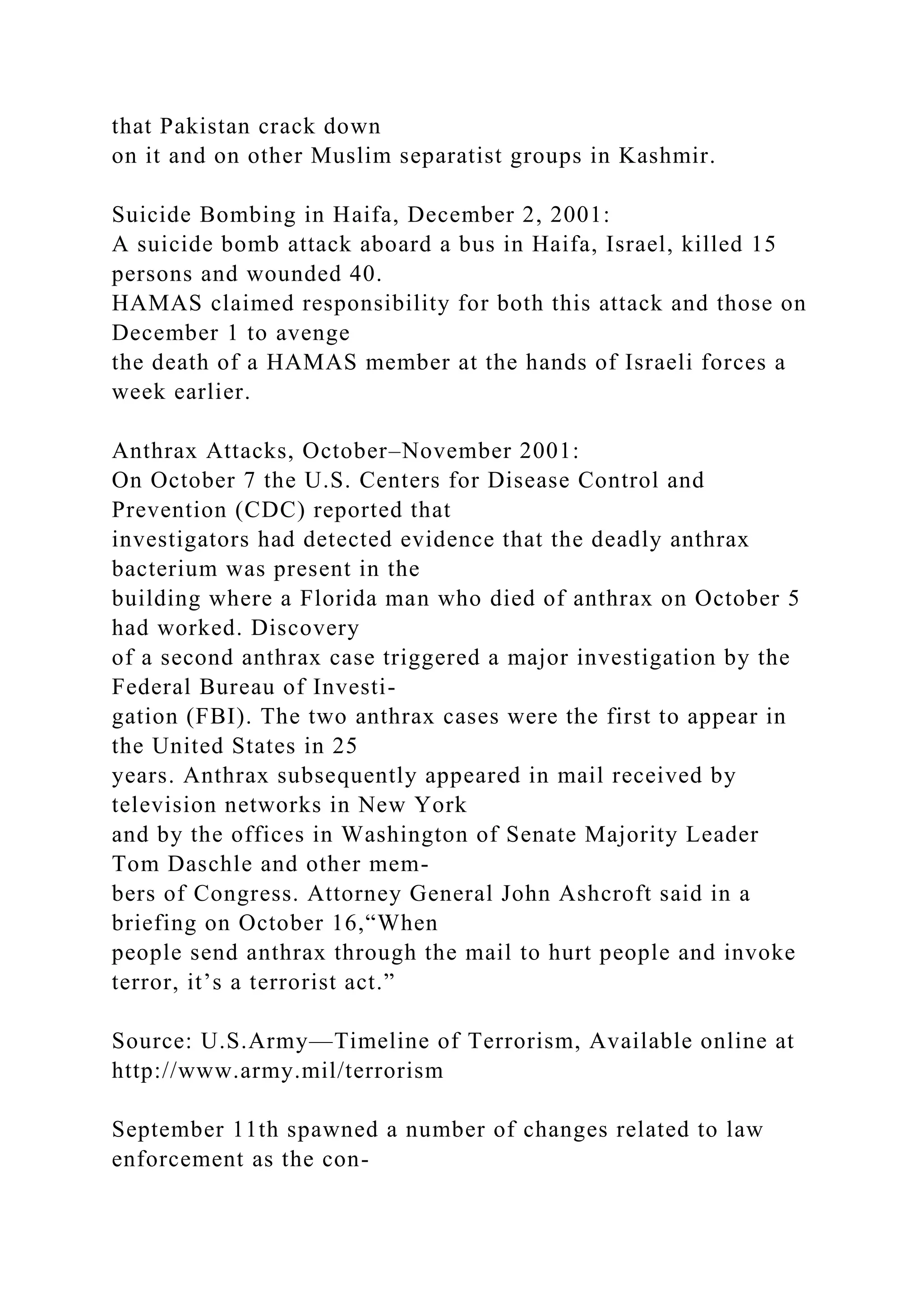

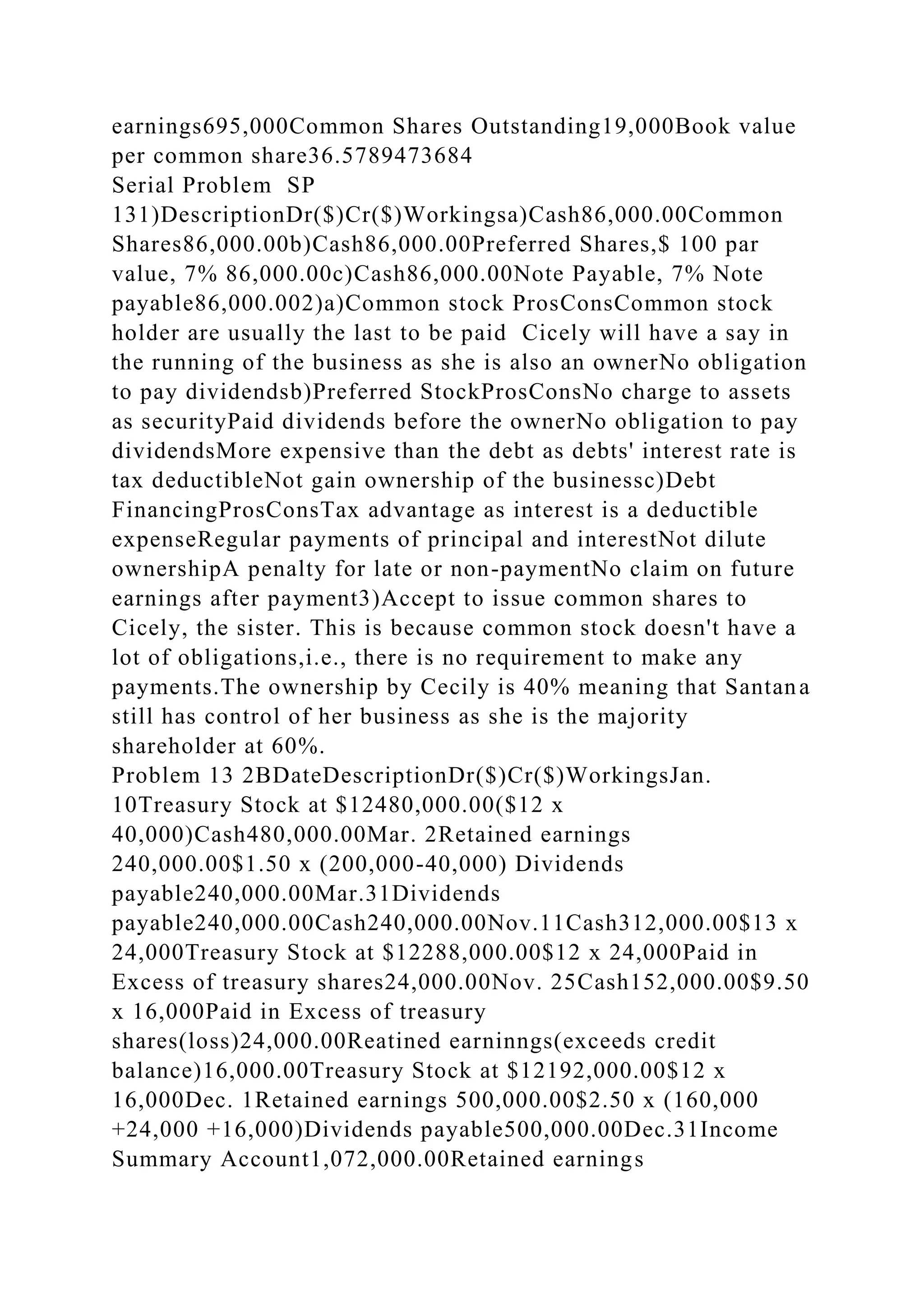

![1,072,000.002)Statement of Retained Earnings$Retained

Earnings (As at 1.1.2016)2,160,000.00Dividends

payable(240,000.00)Treasury stock(16,000.00)Dividends

payable(500,000.00)Income Summary

Account1,072,000.00Retained Earnins (As at

31.12.2016)2,476,000.003)Stockholders' EquityPaid-In

CapitalCommon Shares- $1 per value , 320, 000 shares

authorized, 200,000 shares isued and

outstanding200,000.00Paid-in Capital in Excess of par value,

common stock1,400,000.00Paid in Capital from Treasury

Stock16,000.00Retained Earnings2,476,000.00Total

Stockhlders' equity4,092,000.00

[INSERT TITLE HERE] 1

Running head: [INSERT TITLE HERE]

[INSERT TITLE HERE]

Student Name

Allied American University

Author Note

This paper was prepared for [INSERT COURSE NAME],](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/problem14-6aproblem14-6anorwoodsborrowings1-221119031245-d49f3303/75/PROBLEM-14-6AProblem-14-6A-Norwoods-Borrowings1-Total-amount-of-docx-181-2048.jpg)

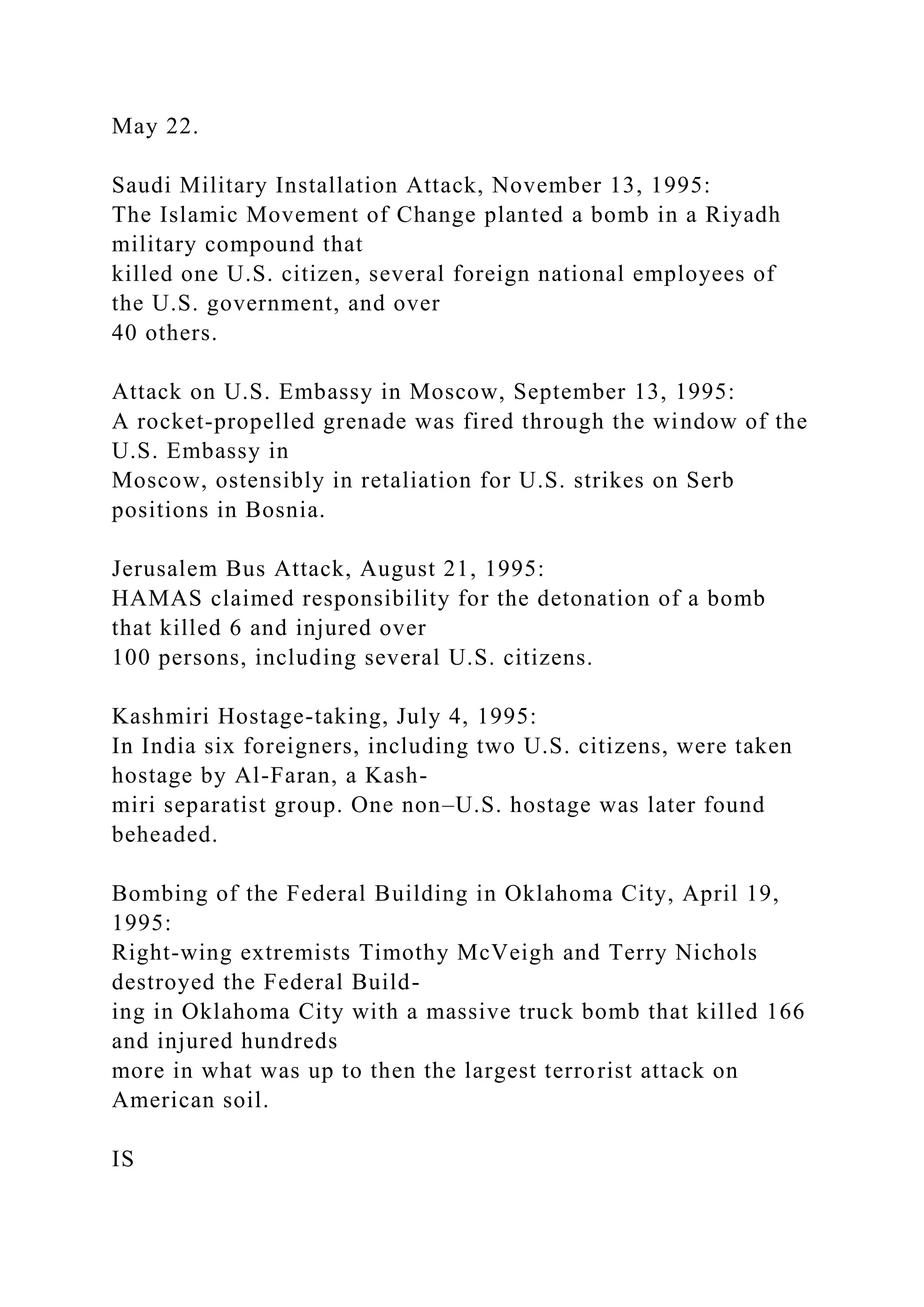

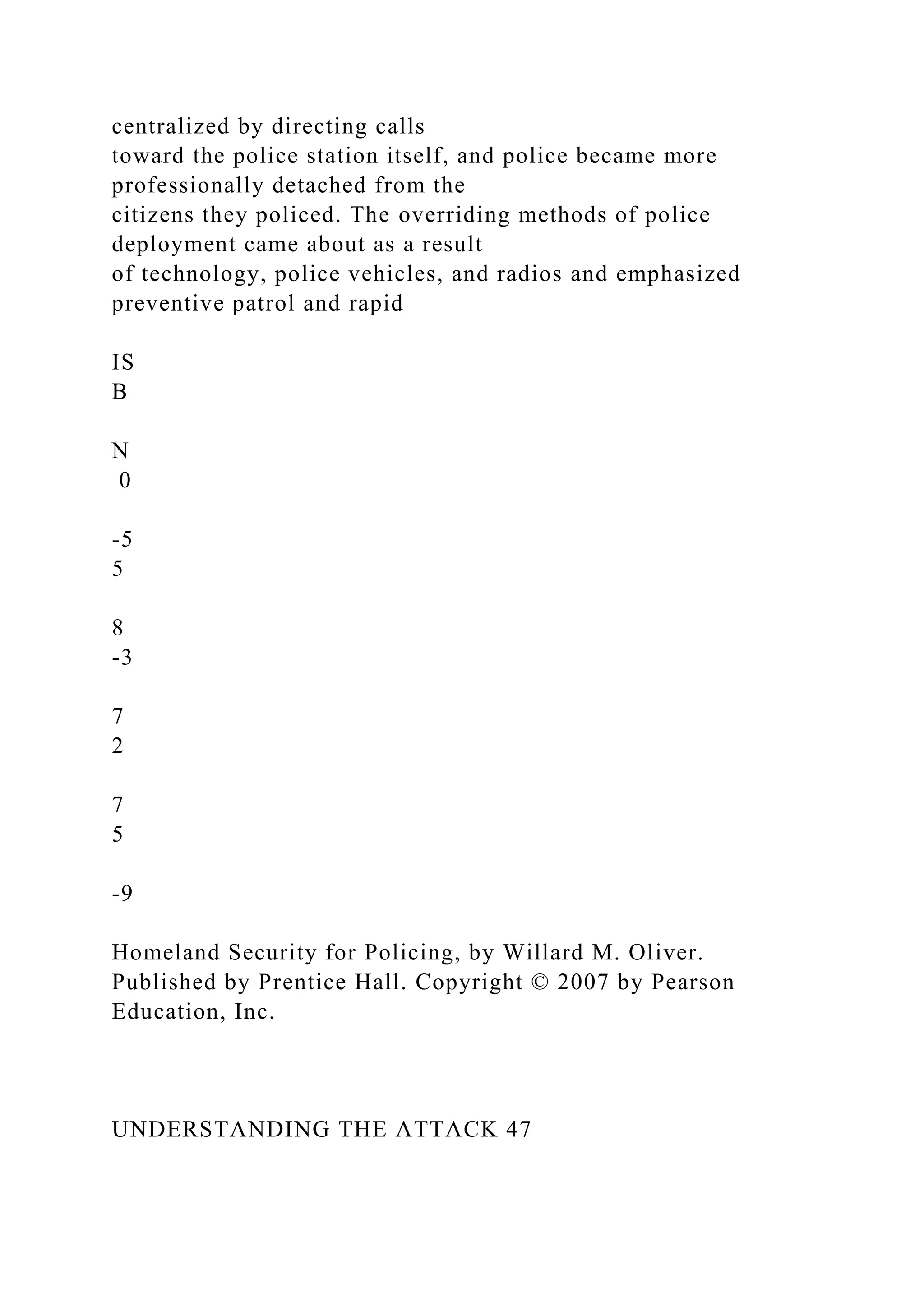

![[INSERT COURSE ASSIGNMENT] taught by [INSERT

INSTRUCTOR’S NAME].

ACC 227: Principles of Accounting II

Module 3 Homework Assignment

Directions: Please use an Excel Spreadsheet to present your

homework (note: if you have a Mac, you may use Pages).

Accounting homework cannot be accomplished in Microsoft

Word. Please use the presentations that have been provided

with the course as reference. Also, you may use the Generic

Working Papers Excel Workbook found in the Course Resources

to complete this assignment. Please visit the Course Resources

section. Please note that you may have additional written

homework alongside these application assignments.

Please complete the following exercises found at the end

Chapter 15:Problem Set A: Problem 15-1AProblem Set A:

Problem 15-2AProblem Set B: Problem 15-3ASerial Problem:

SP 15, Business

Solution

s (course-long project)

Please complete the following exercises found at the end

Chapter 16:Problem Set A: Problem 16-1AProblem Set A:

Problem 16-2AProblem Set B: Problem 16-3AProblem Set A:

Problem 16-4ASerial Problem: SP 16, Business](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/problem14-6aproblem14-6anorwoodsborrowings1-221119031245-d49f3303/75/PROBLEM-14-6AProblem-14-6A-Norwoods-Borrowings1-Total-amount-of-docx-182-2048.jpg)