1. Psychologists worldwide are focusing greater attention on how psychology can contribute to reducing poverty through special issues in peer-reviewed journals on this topic in mid-2010.

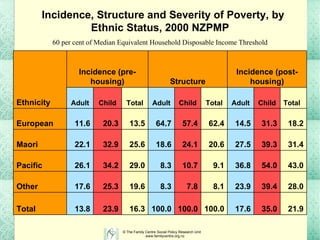

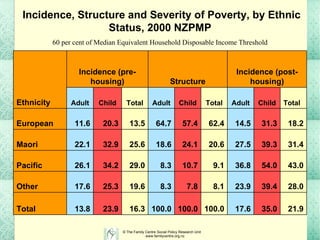

2. Studies show that income inequality is strongly associated with poorer physical and mental health outcomes, and that these health inequalities do not decrease even as overall population health improves.

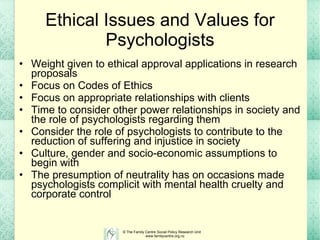

3. Psychologists have an opportunity and ethical responsibility to use their expertise to better describe and address the causes and impacts of poverty and suffering in societies in order to inform policies that can promote well-being and more inclusive communities.