The document discusses the significance of analytics in a big data environment, highlighting various applications for senior-level managers. It covers key topics such as data collection, predictive analytics, and the analytics process model, aimed at equipping professionals with the necessary skills to leverage analytics for strategic advantages. Additionally, it emphasizes practical applications through real-life case studies across multiple industries.

![P R E D I C T I V E A N A L Y T I C S ◂ 37

at time t (see Chapter 5), and

t d the discounting factor (typically the

d

weighted average cost of capital [WACC]). Defining all these param-

eters is by no means a trivial exercise and should be done in close

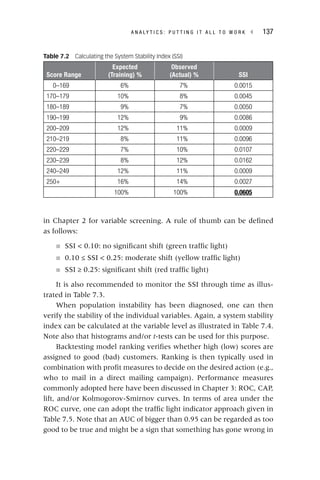

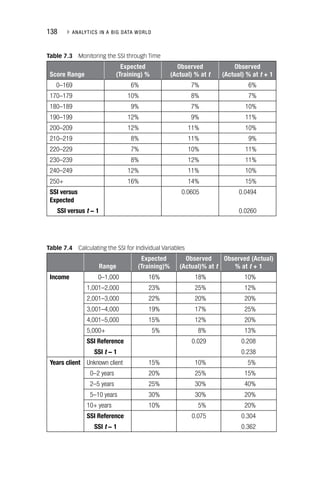

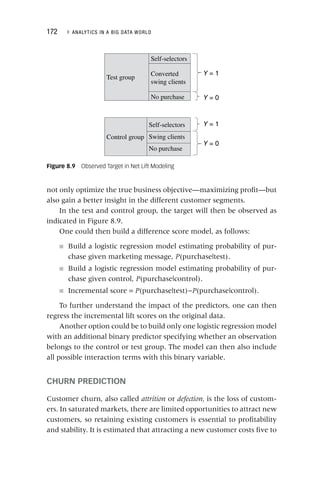

collaboration with the business expert. Table 3.1 gives an example of

calculating CLV.

Loss given default (LGD) is an important credit risk parameter in a

Basel II/Basel III setting.4

It represents the percentage of the exposure

likely to be lost upon default. Again, when defining it, one needs to

decide on the time horizon (typically two to three years), what costs

to include (both direct and indirect), and what discount factor to adopt

(typically the contract rate).

Before starting the analytical step, it is really important to check

the robustness and stability of the target definition. In credit scoring,

one commonly adopts roll rate analysis for this purpose as illustrated

in Figure 3.1. The purpose here is to visualize how customers move

from one delinquency state to another during a specific time frame. It

Table 3.1 Example CLV Calculation

Month t

Revenue in

Month t (Rt)

Cost in Month

t (Ct)

Survival

Probability in

Month t (st)

(Rt − Ct) *

st / (1 + d )t

1 150 5 0.94 135.22

2 100 10 0.92 82.80

3 120 5 0.88 101.20

4 100 0 0.84 84.00

5 130 10 0.82 98.40

6 140 5 0.74 99.90

7 80 15 0.7 45.50

8 100 10 0.68 61.20

9 120 10 0.66 72.60

10 90 20 0.6 42.00

11 100 0 0.55 55.00

12 130 10 0.5 60.00

CLV 937.82

Yearly WACC 10%

Monthly WACC 1%](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phntchtrongbigdata-221113140612-5c05eeb9/85/Phan-tich-trong-Big-Data-pdf-57-320.jpg)

![38 ▸ ANALYTICS IN A BIG DATA WORLD

can be easily seen from the plot that once the customer has reached

90 or more days of payment arrears, he or she is unlikely to recover.

LINEAR REGRESSION

Linear regression is a baseline modeling technique to model a continu-

ous target variable. For example, in a CLV modeling context, a linear

regression model can be defined to model CLV in terms of the RFM

(recency, frequency, monetary value) predictors as follows:

= β + β + β + β

CLV R F M

0 1 2 3

The β parameters are then typically estimated using ordinary least

squares (OLS) to minimize the sum of squared errors. As part of the

estimation, one then also obtains standard errors, p‐values indicating

variable importance (remember important variables get low p‐values),

and confidence intervals. A key advantage of linear regression is that it

is simple and usually works very well.

Note that more sophisticated variants have been suggested in the

literature (e.g., ridge regression, lasso regression, time series mod-

els [ARIMA, VAR, GARCH], multivariate adaptive regression splines

[MARS]).

Figure 3.1 Roll Rate Analysis

Source: N. Siddiqi, Credit Risk Scorecards: Developing and Implementing Intelligent Credit Scoring

(Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2005).

100%

80%

60%

40%

20%

0%

Worst—Next 12 Months

Curr/x day

30 day

60 day

90+

Worst—Previous

12

Months Roll Rate

Curr/x day 30 day 60 day 90+](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phntchtrongbigdata-221113140612-5c05eeb9/85/Phan-tich-trong-Big-Data-pdf-58-320.jpg)

![90 ▸ ANALYTICS IN A BIG DATA WORLD

Again, the data analyst has to specify a minimum confidence (min-

conf) in order for an association rule to be considered interesting.

When considering Table 4.2, the association rule baby food and

diapers ⇒ beer has confidence 3/5 or 60 percent.

Association Rule Mining

Mining association rules from data is essentially a two‐step process as

follows:

1. Identification of all item sets having support above minsup (i.e.,

“frequent” item sets)

2. Discovery of all derived association rules having confidence

above minconf

As said before, both minsup and minconf need to be specified

beforehand by the data analyst. The first step is typically performed

using the Apriori algorithm.1

The basic notion of apriori states that every

i

subset of a frequent item set is frequent as well or, conversely, every

superset of an infrequent item set is infrequent. This implies that can-

didate item sets with k items can be found by pairwise joining frequent

k

item sets with k − 1 items and deleting those sets that have infrequent

k

subsets. Thanks to this property, the number of candidate subsets to

be evaluated can be decreased, which will substantially improve the

performance of the algorithm because fewer databases passes will be

required. The Apriori algorithm is illustrated in Figure 4.1.

Once the frequent item sets have been found, the association rules

can be generated in a straightforward way, as follows:

■ For each frequent item set k, generate all nonempty subsets of k

■ For every nonempty subset s of k, output the rule s ⇒ k −

k s if the

confidence minconf

Note that the confidence can be easily computed using the support

values that were obtained during the frequent item set mining.

For the frequent item set {baby food, diapers, beer}, the following

association rules can be derived:

diapers, beer ⇒ baby food [conf = 75%]

f

baby food, beer ⇒ diapers [conf = 75%]

f](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phntchtrongbigdata-221113140612-5c05eeb9/85/Phan-tich-trong-Big-Data-pdf-110-320.jpg)

![D E S C R I P T I V E A N A L Y T I C S ◂ 91

baby food, diapers ⇒ beer [conf = 60%]

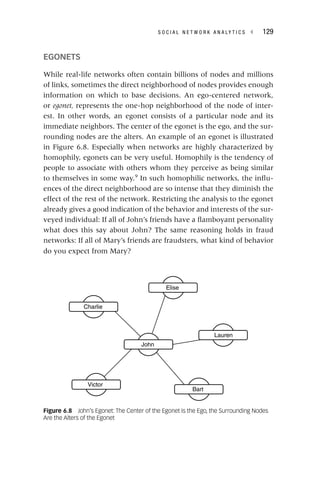

f

beer ⇒ baby food and diapers [conf = 50%]

f

baby food ⇒ diapers and beer [conf = 43%]

f

diapers ⇒ baby food and beer [conf = 43%]

f

If the minconf is set to 70 percent, only the first two association

rules will be kept for further analysis.

The Lift Measure

Table 4.3 provides an example from a supermarket transactions data-

base to illustrate the lift measure.

Let’s now consider the association rule tea ⇒ coffee. The support

of this rule is 100/1,000, or 10 percent. The confidence of the rule is

Table 4.3 The Lift Measure

Tea Not Tea Total

Coffee 150 750 900

Not coffee 50 50 100

Total 200 800 1,000

Figure 4.1 The Apriori Algorithm

Items

TID

1, 3, 4

100

2, 3, 5

200

1, 2, 3, 5

300

2, 5

400

Support

Itemsets

2/4

{1, 3}

2/4

{2, 3}

3/4

{2, 5}

2/4

{3, 5}

L2

Support

Itemsets

1/4

{1, 2}

2/4

{1, 3}

1/4

{1, 5}

2/4

{2, 3}

3/4

{2, 5}

2/4

{3, 5}

C2

Support

Itemsets

2/4

{2, 3, 5}

C3

Result = {{1},{2},{3},{5},{1,3},{2,3},{2,5},{3,5},{2,3,5}}

Support

Itemsets

2/4

{2, 3, 5}

L3

Minsup = 50%

Database

Support

Itemsets

2/4

{1}

3/4

{2}

3/4

{3}

3/4

{5}

L1

{1,3} and {2,3} give

{1,2,3}, but because {1,2}

is not frequent, you do not

have to consider it!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phntchtrongbigdata-221113140612-5c05eeb9/85/Phan-tich-trong-Big-Data-pdf-111-320.jpg)

![D E S C R I P T I V E A N A L Y T I C S ◂ 95

A sequential version can then be obtained as follows:

Session 1: A, B, C

Session 2: B, C

Session 3: A, C, D

Session 4: A, B, D

Session 5: D, C, A

One can now calculate the support in two different ways. Con-

sider, for example, the sequence rule A ⇒ C. A first approach would

be to calculate the support whereby the consequent can appear in any

subsequent stage of the sequence. In this case, the support becomes

2/5 (40%). Another approach would be to only consider sessions in

which the consequent appears right after the antecedent. In this case,

the support becomes 1/5 (20%). A similar reasoning can now be fol-

lowed for the confidence, which can then be 2/4 (50%) or 1/4 (25%),

respectively.

Remember that the confidence of a rule A1 ⇒ A2 is defined as the

probability P(A2 |A1) = support(A1 ∪ A2)/support(A1). For a rule with

multiple items, A1 ⇒ A2 ⇒ … An–1 ⇒ An, the confidence is defined as

P(An |A1, A2, …, An–1), or support(A1 ∪ A2 ∪ … ∪ An–1 ∪ An)/support

(A1 ∪ A2 ∪ … ∪ An–1).

SEGMENTATION

The aim of segmentation is to split up a set of customer observa-

tions into segments such that the homogeneity within a segment is

maximized (cohesive) and the heterogeneity between segments is

maximized (separated). Popular applications include:

■ Understanding a customer population (e.g., targeted marketing

or advertising [mass customization])

■ Efficiently allocating marketing resources

■ Differentiating between brands in a portfolio

■ Identifying the most profitable customers

■ Identifying shopping patterns

■ Identifying the need for new products](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phntchtrongbigdata-221113140612-5c05eeb9/85/Phan-tich-trong-Big-Data-pdf-115-320.jpg)

![100 ▸ ANALYTICS IN A BIG DATA WORLD

Self‐Organizing Maps

A self‐organizing map (SOM) is an unsupervised learning algorithm

that allows you to visualize and cluster high‐dimensional data on a

low‐dimensional grid of neurons.3

An SOM is a feedforward neural

network with two layers. The neurons from the output layer are usu-

ally ordered in a two‐dimensional rectangular or hexagonal grid (see

Figure 4.10). For the former, every neuron has at most eight neigh-

bors, whereas for the latter every neuron has at most six neighbors.

Each input is connected to all neurons in the output layer with

weights w = [

w w1, …, wN

w ], with

N

N N the number of variables. All weights

N

are randomly initialized. When a training vector x is presented, the

x

weight vector wc of each neuron

c c is compared with

c x, using, for

example, the Euclidean distance metric (beware to standardize the

data first):

d x w x w

c i ci

i

N

( , ) ( )2

1

∑

= −

=

x in Euclidean sense is called

x

the best matching unit (BMU). The weight vector of the BMU

and its neighbors in the grid are then adapted using the following

learning rule:

w t w t h t x t w t

i i ci i

( 1) ( 1) ( ) ( ) ( )

[ ]

+ = + + −

whereby t represents the time index during training and

t hci(

i t) defines

t

the neighborhood of the BMU c, specifying the region of influence. The

Figure 4.10 Rectangular versus Hexagonal SOM Grid

Rectangular SOM Grid Hexagonal SOM Grid](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phntchtrongbigdata-221113140612-5c05eeb9/85/Phan-tich-trong-Big-Data-pdf-120-320.jpg)

![112 ▸ ANALYTICS IN A BIG DATA WORLD

Note that the logarithmic transform is used here to make sure that

the hazard rate is always positive.

The Weibull distribution is another popular choice for a parametric

survival analysis model. It is defined as follows:

= κρ ρ − ρ

κ− κ

f t t t

( ) ( ) exp[ ( ) ]

1

The survival function then becomes:

= − ρ κ

S t t

( ) exp[ ( ) ]

and the hazard rate

= = κρ ρ κ−

h t

f t

S t

t

( )

( )

( )

( ) 1

Note that in this case the hazard rate does depend on time and can

be either increasing or decreasing (depending upon κ and ρ).

When including covariates, the model becomes:

( ) = μ + α + β + β + β

log ( , ) log( ) 1 1 2 2

h t x t x x x

i i i N iN

Other popular choices for the event time distribution are the

gamma, log‐logistic, and log‐normal distribution.3

Parametric survival analysis models are typically estimated using

maximum likelihood procedures. In case of no censored observations,

the likelihood function becomes:

∏

=

=

L f t

i

n

i

( )

1

When censoring is present, the likelihood function becomes:

L f t S t

i

n

i i

i i

∏ ( )

=

=

δ −δ

( )

1

1

i

δ equals 0 if observation i is censored, and 1 if the observa-

i

tion dies at time ti.

i It is important to note here that the censored obser-

vations do enter the likelihood function and, as such, have an impact

on the estimates. For example, for the exponential distribution, the

likelihood function becomes:

L e e

t

i

n

t

i i i i

∏

= λ −λ δ

=

−λ −δ

[ ] [ ]

1

1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phntchtrongbigdata-221113140612-5c05eeb9/85/Phan-tich-trong-Big-Data-pdf-132-320.jpg)

![182 ▸ ANALYTICS IN A BIG DATA WORLD

different knowledge sources are used to obtain features, and these are

then given to the recommendation algorithm. A fifth type is feature

augmentation: A first recommender computes the features while the

next recommender computes the remainder of the recommendation.

For example, Melville, Mooney, and Nagarajan27

use a content‐based

model to generate ratings for items that are unrated and then col-

laborative filtering uses these to make the recommendation. Cascade

is the sixth type of hybrid technique. In this case, each recommender

is assigned a certain priority and if high priority recommenders pro-

duce a different score, the lower priority recommenders are decisive.

Finally, a meta‐level hybrid recommender system consists of a first

recommender that gives a model as output that is used as input by

the next recommender. For example, Pazzani28

discusses a restaurant

recommender that first uses a content‐based technique to build user

profiles. Afterward, collaborative filtering is used to compare each

user and identify neighbors. Burke29

states that a meta‐level hybrid is

different from a feature augmentation hybrid because the meta‐level

hybrid does not use any original profile data; the original knowledge

source is replaced in its entirety.

Evaluation of Recommender Systems

Two categories of evaluation metrics are generally considered:30

the

goodness or badness of the output presented by a recommender

system and its time and space requirements. Recommender systems

generating predictions (numerical values corresponding to users’ rat-

ings for items) should be evaluated separately from recommender

systems that propose a list of N items that a user is expected to find

N

interesting (top‐N recommendation). The first category of evaluation

N

metrics that we consider is the goodness or badness of the output pre-

sented by a recommender system. Concerning recommender systems

that make predictions, prediction accuracy can be measured using

statistical accuracy metrics (of which mean absolute deviation [MAD]

is the most popular one) and using decision support accuracy met-

rics (of which area under the receiver operating characteristic curve

is the most popular one). Coverage denotes for which percentage of

the items the recommender system can make a prediction. Coverage](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/phntchtrongbigdata-221113140612-5c05eeb9/85/Phan-tich-trong-Big-Data-pdf-202-320.jpg)