This document provides an overview of social pedagogy seminars being offered in May through July 2007. It includes definitions of social pedagogy from key thinkers in the field, focusing on social pedagogy as educational action to help the poor in society and promote human welfare. The document also outlines several principles of a pedagogic approach including seeing the child as a whole person and the importance of relationships between practitioners and children.

![Social Pedagogy Seminars

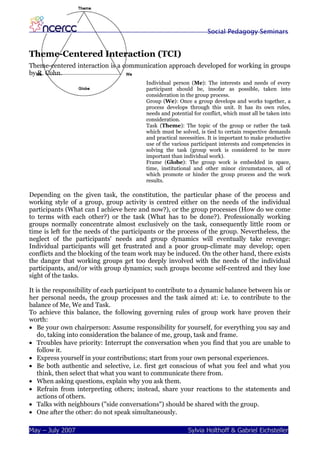

What is (social) pedagogy?

Etymology:

The word pedagogy stems from the Greek pais: child, and agein: to lead, bring up.

British interpretations:

Children’s Workforce Development Council (CWDC)

‘The pedagogical approach rests on an image of a child as a complex social being with rich

and extraordinary potential, rather than as an adult-in-waiting who needs to be given the

right ingredients for optimal development. […] For pedagogues there is no universal

solution, each situation requires a response based on a combination of information,

emotions, self-knowledge and theory.’

Petrie et al. (2006, p22) found nine principles of a pedagogic approach:

• ‘A focus on the child as a whole person, and support for the child’s overall development;

• The practitioner seeing herself/himself as a person, in relationship with the child or

young person;

• Children and staff are seen as inhabiting the same life space, not as existing in separate

hierarchical domains;

• As professionals, pedagogues are encouraged constantly to reflect on their practice and

to apply both theoretical understandings and self-knowledge to the sometimes

challenging demands with which they are confronted;

• Pedagogues are also practical, so their training prepares them to share in many aspects

of children’s daily lives and activities;

• Children’s associative life is seen as an important resource: workers should foster and

make use of the group;

• Pedagogy builds on an understanding of children’s rights that is not limited to

procedural matters or legislated requirements;

• There is an emphasis on team work and on valuing the contribution of others in

“bringing up” children: other professionals, members of the local community and,

especially, parents;

• The centrality of relationship and, allied to this, the importance of listening and

communicating.’

Cannan et al. (1992, pp73) defined social pedagogy as ‘a perspective, including social action

which aims to promote human welfare through child-rearing and education practices; and

to prevent or ease social problems by providing people with the means to manage their own

lives, and make changes in their circumstances’.

May – July 2007 Sylvia Holthoff & Gabriel Eichsteller](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pedagogueulltrainingpack2-100128053713-phpapp01/85/Social-Pedagogy-Training-Pack-4-320.jpg)

![Social Pedagogy Seminars

ourselves to a sense of the inner dignity of our nature, and of the pure, higher, godly being,

which lies within us. This sense is not developed by the power of our mind in thought, but

is developed by the power of our heart in love.’ For Pestalozzi, moral education aimed to

convey Christian values to the children, which meant that the pedagogue had to live these

values. Consequently, Pestalozzi abolished caning in his institution. Pestalozzi also realised

that children learn through physical activities, as ‘physical experiences give rise to mental

and spiritual ones’. Consequently, his method paid special attention to the ‘hands’ – or

more exactly the whole body – as understanding the world, being in direct contact with the

world and grasping things. He emphasized the importance of tactile perception and pointed

out that physical education also contributed to a healthy development.

The three elements ‘head, heart, and hands’ are inseparable from each other in Pestalozzi’s

method. ‘Nature forms the child as an indivisible whole, as a vital organic unity with many

sided moral, mental, and physical capacities. Each of these capacities is developed through

and by means of the others,’ Pestalozzi stated.

To be educative in a holistic sense, Pestalozzi demanded that learning be based on the

individual child’s understanding, on ‘close observation of children and on deep insight into

the way a child’s mind works and develops’. This form of reflective practice is stated in his

doctrine of Anschauung, of direct observation. Through observation, the pedagogue aims

to ‘find out the capacities of each individual child’ and to support him in his unique natural

development. Hence observation is needed, because it is not the pedagogue who forms the

child; the potentiality of each child is implemented by nature as ‘a little seed contains the

design of a tree’. And the pedagogue’s role is to take care ‘that no untoward influence shall

disturb nature’s march of developments’.

Pestalozzi’s child-centred approach especially emphasises the relationship between the

pedagogue and child. Describing love as ‘the sole, the everlasting foundation’ for education

without which ‘neither the physical not the intellectual powers [would] develop naturally’,

Pestalozzi assumed that without a satisfying, especially emotional, acceptance of the child

all pedagogy would fail – something we would nowadays call ‘openness’, ‘empathy’, and

‘affection’.

Nearly two centuries after the death of Pestalozzi his formulated method of the ‘head, heart

and hands’ can be found in other definitions of holistic education. Studies with Danish and

German pedagogues show that these terms are still key words used to describe a pedagogic

working style – and they also demand that pedagogues work with ‘head, heart, and hands’,

use their cognitive, physical and emotional skills.

Pestalozzi is also relevant for current practice, because he fought for social justice and was

committed to working ‘with those who have suffered within society. He saw education as

central to the improvement of social conditions’. This shows that there is much brilliance

and relevance to be found in Pestalozzi’s thought. Pedagogues, and among them youth

workers, must not forget his initiative; moreover they should cherish his ideas by applying

them in everyday-practice. Surely, these ideas cannot be put into the contemporary context

of pedagogy without reflection – but then, it was Pestalozzi himself who demanded

reflective practice.

Further readings:

The key text is the ‘classic’ Pestalozzi text on education

Pestalozzi, J.H. (1894): How Gertrude teaches her children, translated by Lucy, E. Holland

and Frances C. Turner. Edited with an introduction by Ebenezer Cooke.

London: Swan Sonnenschein

May – July 2007 Sylvia Holthoff & Gabriel Eichsteller](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pedagogueulltrainingpack2-100128053713-phpapp01/85/Social-Pedagogy-Training-Pack-7-320.jpg)

![Social Pedagogy Seminars

Under this frame, he formulated three key rights – ‘perhaps there are more, but I have

found these to be the principle rights’:

1) The right of the child to die.

2) The right of the child to live for today.

3) The right of the child to be what she or he is.

As Korczak said, out of fear that death could snatch away our child, we deprive him of life;

to avert his death we don’t really let him live. In this sense, the right to die puts the right to

a self-determined life, with all its risks and hazards, out of adults’ hands and in the hands of

the child. He pointed out that overprotection disregards the children’s right to freedom,

self-experience and self-determination; hence the right to die is ultimately the right to take

responsibility for one’s own life and death.

Korczak’s formulation of the child’s right to the present day means that ‘we should also

respect the present hour. How can we assure a child’s life in the future, if we have not yet

learned how to live consciously and responsibly in the present?’ It is not the pedagogue’s

task to influence the future fate of the child, but to ensure that the present day is ‘full of

happy efforts, child-like, carefree without a responsibility that exceeds the age and the

powers’.

Korczak’s demand that children be allowed to be who they are is also linked with this

concept of children as full persons, and his notion that we cannot expect from children to

be perfect. This right also calls for a relational approach, as it is our responsibility to get to

know the child.

A little later Korczak added that ‘the primary and indisputable right of the child is to

pronounce his thoughts and to take actively part in our considerations and decisions about

his person’. Characteristic for Korczak’s pedagogic approach is the radical involvement of

children: self-governing structures are at the heart of his education system, ensuring that

the basis for a discourse between child and adult is independent from the adult’s

humanistic attitude.

Korczak’s pedagogic ideas were based on his high interest in everything children did; he

was a practitioner-researcher with his whole heart. He emphasised how studying, observing

and asking children can lead to a better understanding of them. His constant observations

and reflections also enabled him to experiment with new structures and to analyse where

they needed improvement. ‘Thanks to theory, I know. Thanks to practice, I feel. Theory

enriches intellect, practice deepens feeling, trains the will’.

Korczak always emphasised the individuality of each child, stating that there is no recipe

for rearing children: ‘it is impossible to tell parents unknown to me how to rear a child also

unknown to me under conditions unknown to me […] There are insights that can be born

only of your own pain, and they are the most precious.’

further readings:

Korczak, J. (2007). Loving every Child – Wisdom for Parents. Edited by S. Joseph. Chapel

Hill: Algonquin Books.

Lewowicki, T. (1997). Janusz Korczak. In E. Morsy-Zaghloul (ed.). Thinkers on Education.

Vol. 3. Paris: UNESCO. Available online:

http://www.ibe.unesco.org/publications/ThinkersPdf/

korczaks.PDF

Lifton, B.J. (1988). The King of Children: A Biography of Janusz Korczak. London: Chatto

& Windus. Available online: http://korczak.com/Biography/kap-0.htm

May – July 2007 Sylvia Holthoff & Gabriel Eichsteller](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pedagogueulltrainingpack2-100128053713-phpapp01/85/Social-Pedagogy-Training-Pack-12-320.jpg)

![6. ‘Young people can feel restricted if were happy that the guidelines existed

peers who are not looked after are and were applied.

permitted by parents to take part in They thought that the rules and

activities denied to looked after guidelines which existed were necessary

[children].’ and valid, even though they

The findings from the unit managers’ acknowledged that this had an effect on

questionnaire indicate a real concern the spontaneity of activities. As members

from this group about the practices in of staff, they felt safeguarded as long as

relation to health and safety guidelines. they followed the guidance. There was a

Although concern about safety in the sense that if guidelines were not followed,

countryside or at the beach is valid, the this could lead to disciplinary action

way such regulations are being against the staff member. The responses

interpreted cuts across the principles of from basic grade staff were different from

normalization and respect for the responses of unit managers, and

individuality, and may infringe the different concerns were apparent between

human rights of the young person in the groups.

residential care. They represent a real and

damaging set of practices that have Focus group discussion with young

emerged in the last few years. They are people

damaging not only because they restrict Four separate focus group discussions

the possibilities for normal living, and the were held in locations around Scotland.

simple physical and emotional health The young people who took part were

benefits of fun and exercise, but also between the ages of 15 and 19 years, and

because they undermine the confidence of they were all in residential care. The task

residential child care staff and contribute of the focus groups was to discuss

to a culture of dis-empowerment. Standards 9 and 15 of the National Care

Standards: Care Homes for Children and

Interviews with basic grade residential Young People (Scottish Executive, 2002).

staff Standard 9 is concerned with making

The interviews with the basic grade choices. The standard says that the young

residential staff to an extent painted a person should live in a place where

different picture from that of the unit everyone respects and supports their

managers. A total of seven basic grade personal choices, and the seven elements

staff were interviewed by telephone. Staff relate the principle of choice to a range of

felt that there were restrictions on practices, from participating in care

activities but seemed content with this. decisions to deciding how to spend pocket

Although unit managers reported that money or be consulted about décor. Over

children and young people did have half of the young people felt that they

access to outdoor recreational activities, were able to choose what they wanted to

basic grade staff reported that they rarely do but that this sometimes depended on

took young people on outdoor activities which staff members were on duty. The

such as fishing, walking in the country or responses from young people gave a sense

going to the beach. Only one of the staff that some degree of negotiation went on

had a qualification (pool lifeguard). If with staff to ensure that safe and

outdoor activities were being undertaken, appropriate choices were being made.

risk assessments had to be completed, Choices about outdoor activities were

and permissions had to be obtained either constrained by staff availability.

from parents or from social workers. Standard 15 is about daily life. This

Although staff reported that there were standard states that young people should

restrictions on activities, they felt that this be made to feel a part of their unit and

was acceptable as the young people community. Only one young person

needed to be kept safe. In general, they reported that they were never encouraged

to have and maintain hobbies and](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pedagogueulltrainingpack2-100128053713-phpapp01/85/Social-Pedagogy-Training-Pack-97-320.jpg)

![one should not try to consciously control report knowing very clearly what they

what one is doing. have to do moment by moment, either

because the activity requires it (as when

As the composer stated, when the the score of a musical composition

conditions are right, action “just flows out specifies what notes to play next), or

by itself.” It is because so many because the person sets clear goals every

respondents used the analogy of step of the way (as when a rock climber

spontaneous, effortless flow to describe decides which hold to try for next).

how it felt when what they were doing was Second, they are able to get immediate

going well that I used the term flow to feedback on what they are doing. Again,

describe the autotelic experience. Here is this might be because the activity provides

what a well-know lyricist, a former poet information about the performance (as

laureate of the United States, said about when one is playing tennis and after each

his writing: shot one knows whether the ball went

where it was supposed to go), or it might

You lose your sense of time, you're be because the person has an internalized

completely enraptured, you are standard that makes it possible to know

completely caught up in what you're whether one's actions meet the standard

doing, and you are sort of swayed by the (as when a poet reads the last word or the

possibilities you see in this work. If that last sentence written and judges it to be

becomes too powerful, then you get up, right or in need of revision).

because the excitement is too great …. The

idea is to be so, so saturated with it that Another universal condition for the flow

there's no future or past, it's just an experience is that the person feels his or

extended present in which you are … her abilities to act match the

making meaning. And dismantling opportunities for action. If the challenges

meaning, and remaking it. are too great for the person's skill, anxiety

(Csikszentmihalyi, 1996, p. 121) is likely to ensue; if the skills are greater

than the challenges, one feels bored.

This kind of intense experience is not When challenges are in balance with

limited to creative endeavors. It is skills, one becomes lost in the activity and

reported by teenagers who love studying, flow is likely to result (Csikszentmihalyi,

by workers who like their jobs, by drivers 1975, 1997).

who enjoy driving. Here is what one

woman said about her sources of deepest Even this greatly compressed summary of

enjoyment: the flow experience should make it clear

that it has little to do with the widespread

[It happens when] I am working with my cultural trope of “going with the flow.” To

daughter, when she's discovered go with the flow means to abandon

something new. A new cookie recipe that oneself to a situation that feels good,

she has accomplished, that she has made natural, and spontaneous. The flow

herself, an artistic work that she's done experience that I have been studying is

and she is proud of. Her reading is something that requires skills,

something that she is really into, and we concentration, and perseverance.

read together. She reads to me and I read However, the evidence suggests that it is

to her, and that's a time when I sort of the second form of flow that leads to

lose touch with the rest of the world. I am subjective well-being.

totally absorbed in what I am doing.

(Allison & Duncan, 1988, p. 129) The relationship between flow and

happiness is not entirely self-evident.

This kind of experience has a number of Strictly speaking, during the experience

common characteristics. First, people people are not necessarily happy because](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pedagogueulltrainingpack2-100128053713-phpapp01/85/Social-Pedagogy-Training-Pack-104-320.jpg)

![of children at home and away from home.

Child Care Quarterly, 8(4), 161-173.

Maier H (1982) 'The Space We Create

Controls Us' Residential Group Care and

Treatment Vol 1 (1).

Murphy Z and Graham G. (2002) Life

Space Intervention Training Video and

Manual for Residential Care Dublin

Institute of Technology

Phelan, J. (2001) Experiential Counselling

and the CYC Practitioner. Journal of

Child and Youth Care Work, 15 and 16

special edition, 256-263.

Redl, F., & Wineman, D. (1951). Children

who Hate. Glencoe, IL: Free Press.

Redl, F., & Wineman, D. (1957). Controls

from within: Techniques for treatment of

the aggressive child. New York: Free Press.

Ricks, F. (1989) Self-awareness model for

training and application in child and youth

care. Journal of Child and Youth Care,

8(3), 17-34

Trieschman, A., Whittaker, J., & Brendtro,

L. (1969). The other twenty three hours.

New York: Aldine.

Trieschman, A. (1982). The anger within.

[Videotape interview.] Washington, DC:

NAK Productions.

In addition, access to a range of literature

and ideas on working with children and

young people can be found on the web

site: cyc-net.org](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/pedagogueulltrainingpack2-100128053713-phpapp01/85/Social-Pedagogy-Training-Pack-117-320.jpg)