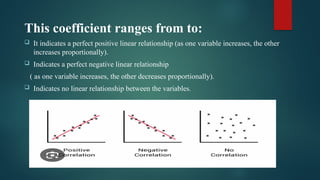

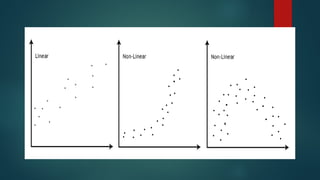

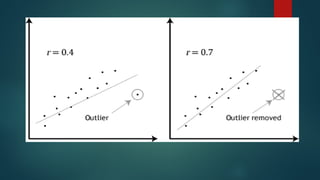

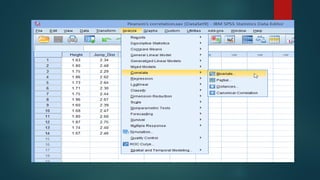

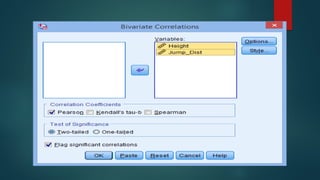

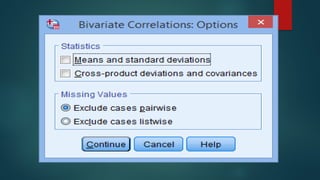

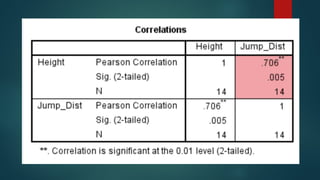

Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficient measures the strength and direction of the association between two continuous variables on at least an interval scale, indicating positive, negative, or no linear relationships. It requires data to meet four assumptions: measurement at the interval or ratio level, linearity of relationship, absence of significant outliers, and approximate normal distribution. The document also includes examples of using Pearson's correlation to assess relationships between height and long jump performance, as well as study hours and exam scores.