The document is an overview of the fourth edition of 'Nursing Research: Reading, Using, and Creating Evidence' by Janet Houser, aimed at providing nursing students and professionals with a comprehensive understanding of how to utilize research in clinical practice. It discusses various aspects of nursing research, including the importance of evidence-based practice, ethical considerations, and different types of research methodologies, while also addressing contemporary issues in the field. The text is structured to facilitate understanding for beginners and enhance the research skills of experienced nurses, encouraging active participation in research processes.

![NURSING RESEARCH

READING, USING, AND CREATING EVIDENCE

FOURTH EDITION

JANET HOUSER, PHD, RN

Provost and Professor

Rueckert-Hartman College for Health Professions

Regis University

Denver, Colorado

JONES & BARTLETT

LEARNING

2

World Headquarters

Jones & Bartlett Learning

5 Wall Street

Burlington, MA 01803

978-443-5000

[email protected]

www.jblearning.com

Jones & Bartlett Learning books and products are available

through most

bookstores and online booksellers. To contact Jones & Bartlett

Learning](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/75/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-1-2048.jpg)

![directly, call 800-832-0034, fax 978-443-8000, or visit our

website,

www.jblearning.com.

Substantial discounts on bulk quantities of Jones & Bartlett

Learning

publications are available to corporations, professional

associations, and

other qualified organizations. For details and specific discount

information,

contact the special sales department at Jones & Bartlett

Learning via the

above contact information or send an email to

[email protected]

Copyright © 2018 by Jones & Bartlett Learning, LLC, an

Ascend Learning

Company

All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this

copyright may be

reproduced or utilized in any form, electronic or mechanical,

including

photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and

retrieval system,

without written permission from the copyright owner.

The content, statements, views, and opinions herein are the sole

expression of

the respective authors and not that of Jones & Bartlett Learning,

LLC.

Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process,

or service by

trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not

constitute or

imply its endorsement or recommendation by Jones & Bartlett

Learning, LLC](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-2-320.jpg)

![Cover Design: Scott Moden

Rights & Media Specialist: Wes DeShano

Media Development Editor: Troy Liston

Cover Image: © Valentina Razumova/Shutterstock

Printing and Binding: LSC Communications

Cover Printing: LSC Communications

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Houser, Janet, 1954- author.

Title: Nursing research : reading, using, and creating evidence /

Janet Houser.

Description: Fourth edition. | Burlington, Massachusetts : Jones

& Bartlett

Learning, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and

index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016038194 | ISBN 9781284110043

Subjects: | MESH: Clinical Nursing Research--methods |

Evidence-Based

4

Nursing | Research Design

Classification: LCC RT81.5 | NLM WY 20.5 | DDC 610.73072--

dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016038194

6048

Printed in the United States of America

20 19 18 17 16 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-5-320.jpg)

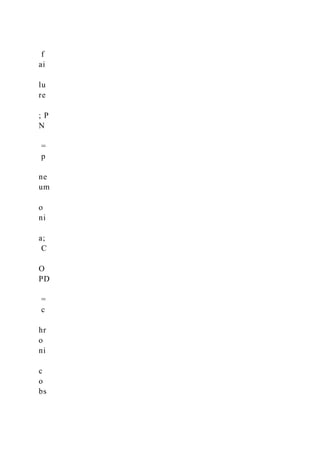

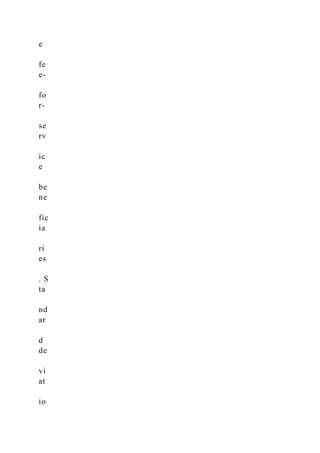

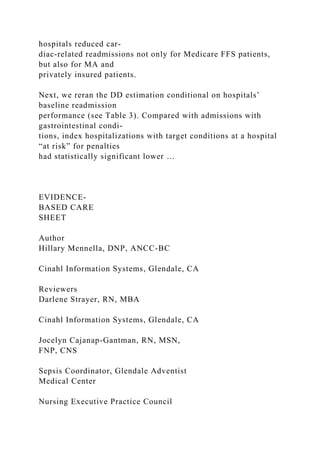

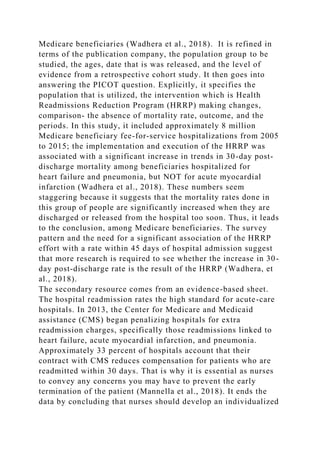

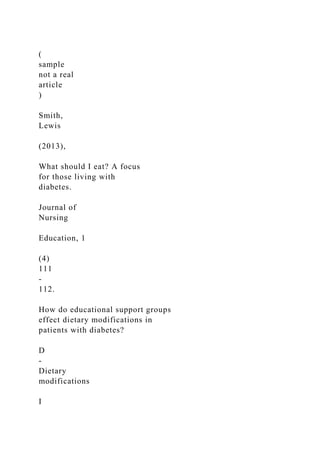

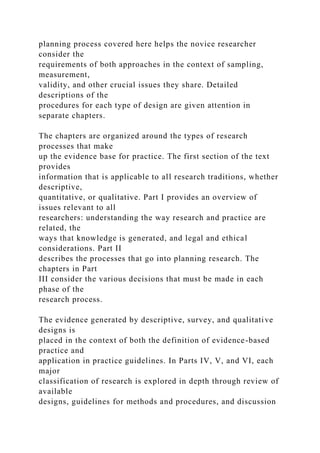

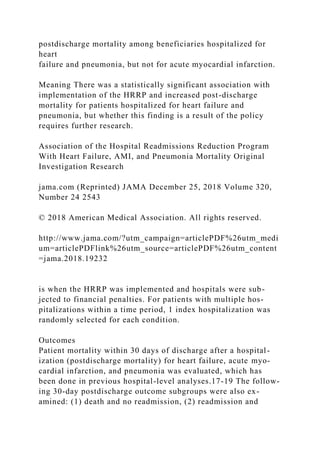

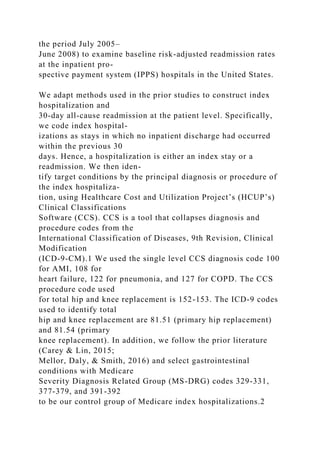

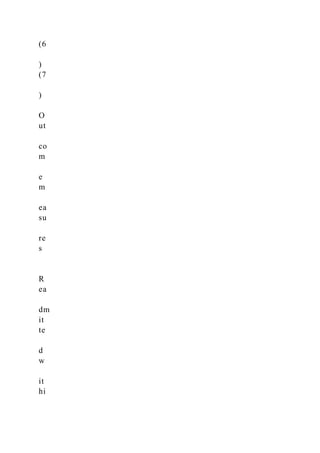

![EXPOSURES Announcement and implementation of the HRRP.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Inverse probability–

weighted mortality within 30 days of

discharge following hospitalization for HF, AMI, and

pneumonia, and stratified by whether

there was an associated readmission. An additional end point

was mortality within 45 days of

initial hospital admission for target conditions.

RESULTS The study cohort included 8.3 million

hospitalizations for HF, AMI, and pneumonia,

among which 7.9 million (mean age, 79.6 [8.7] years; 53.4%

women) were alive at discharge.

There were 3.2 million hospitalizations for HF, 1.8 million for

AMI, and 3.0 million for pneumonia.

There were 270 517 deaths within 30 days of discharge for HF,

128 088 for AMI, and 246 154 for

pneumonia. Among patients with HF, 30-day postdischarge

mortality increased before the

announcement of the HRRP (0.27% increase from period 1 to

period 2). Compared with this

baseline trend, HRRP announcement (0.49% increase from

period 2 to period 3; difference in

change, 0.22%, P = .01) and implementation (0.52% increase

from period 3 to period 4;

difference in change, 0.25%, P = .001) were significantly

associated with an increase in

postdischarge mortality. Among patients with AMI, HRRP

announcement was associated with a

decline in postdischarge mortality (0.18% pre-HRRP increase vs

0.08% post-HRRP

announcement decrease; difference in change, −0.26%; P = .01)

and did not significantly change

after HRRP implementation. Among patients with pneumonia,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-36-320.jpg)

![Corresponding Authors: Robert W.

Yeh, MD, MSc, and Changyu Shen,

PhD, Smith Center for Outcomes

Research in Cardiology, Beth Israel

Deaconess Medical Center, 375

Longwood Ave, Boston, MA 02215

([email protected]).

Research

JAMA | Original Investigation

2542 (Reprinted) jama.com

© 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

https://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2

018.19232&utm_campaign=articlePDF%26utm_medium=article

PDFlink%26utm_source=articlePDF%26utm_content=jama.2018

.19232

https://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?doi=10.1001/jama.2

018.19325&utm_campaign=articlePDF%26utm_medium=article

PDFlink%26utm_source=articlePDF%26utm_content=jama.2018

.19232

mailto:[email protected]

http://www.jama.com/?utm_campaign=articlePDF%26utm_medi

um=articlePDFlink%26utm_source=articlePDF%26utm_content

=jama.2018.19232

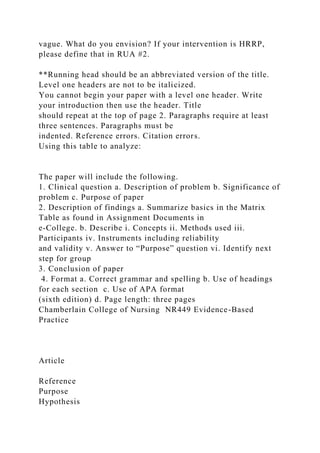

T he Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP)was

established under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in2010 and

required that the Centers for Medicare & Med-

icaid Services (CMS) impose financial penalties on hospitals

with higher-than-expected 30-day readmission rates for pa-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-38-320.jpg)

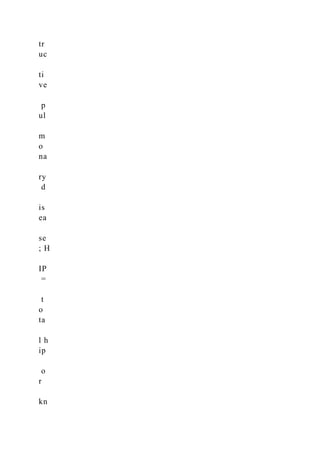

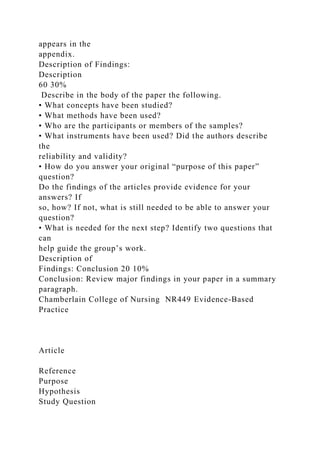

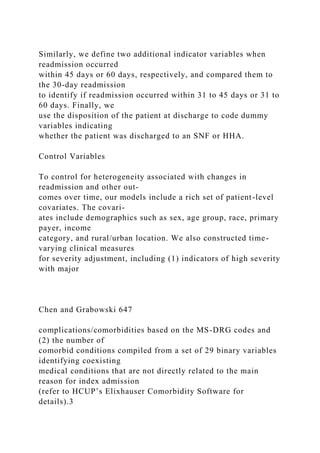

![Min Chen, College of Business, Florida International

University, 11200 SW 8th Street,

Miami, FL 33199, USA.

Email: [email protected]

744611MCRXXX10.1177/1077558717744611Medical Care

Research and ReviewChen and Grabowski

research-article2017

https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/journals-permissions

https://journals.sagepub.com/home/mcr

mailto:[email protected]

http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1177%2F10775587

17744611&domain=pdf&date_stamp=2017-12-03

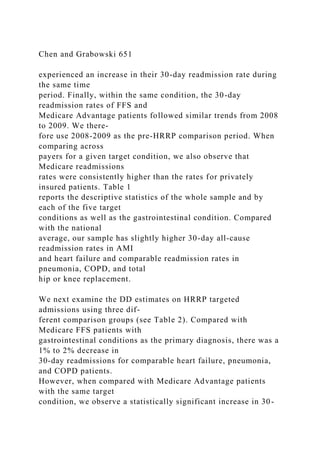

644 Medical Care Research and Review 76(5)

Introduction

Hospital readmissions are common and costly. In 2011, the U.S.

Medicare program

paid for 1.8 million 30-day readmissions with a total cost of $24

billion (Hines, Barrett,

Marguerit, Jiang, Joanna, & Steiner, 2014). Some readmissions

could be prevented

with better quality of care (Axon & Williams, 2011), and the

Medicare Payment

Advisory Commission (MedPAC) estimates that a 10%

reduction in avoidable read-

missions would save the Medicare program at least $1 billion

(MedPAC, 2013). To

achieve both better outcomes for patients and greater savings

for Medicare, the

Affordable Care Act (ACA) created the Hospital Readmissions

Reduction Program](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-58-320.jpg)

![n

30

d

ay

s

0.

16

[

0.

37

]

0.

18

[

0.

38

]

0.

23

[

0.

42

]

0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-75-320.jpg)

![16

[

0.

37

]

0.

19

[

0.

39

]

0.

05

[

0.

25

]

0.

13

[

0.

34

]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-76-320.jpg)

![R

ea

dm

it

te

d

w

it

hi

n

31

-4

5

da

ys

0.

03

[

0.

17

]

0.

03

[

0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-77-320.jpg)

![17

]

0.

05

[

0.

21

]

0.

03

[

0.

17

]

0.

04

[

0.

20

]

0.

01

[

0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-78-320.jpg)

![12

]

0.

03

[

0.

16

]

R

ea

dm

it

te

d

w

it

hi

n

31

-6

0

da

ys](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-79-320.jpg)

![0.

05

[

0.

22

]

0.

05

[

0.

21

]

0.

08

[

0.

27

]

0.

05

[

0.

22

]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-80-320.jpg)

![0.

07

[

0.

25

]

0.

02

[

0.

15

]

0.

05

[

0.

21

]

D

is

ch

ar

ge](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-81-320.jpg)

![d

to

S

N

F

0.

17

[

0.

37

]

0.

13

[

0.

33

]

0.

17

[

0.

37

]

0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-82-320.jpg)

![17

[

0.

38

]

0.

12

[

0.

32

]

0.

39

[

0.

49

]

0.

09

[

0.

29

]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-83-320.jpg)

![D

is

ch

ar

ge

d

to

H

H

A

0.

22

[

0.

41

]

0.

16

[

0.

37

]

0.

25](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-84-320.jpg)

![[

0.

43

]

0.

18

[

0.

38

]

0.

20

[

0.

40

]

0.

45

[

0.

50

]

0.

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-85-320.jpg)

![[

0.

33

]

Pa

ti

en

t

ch

ar

ac

te

ri

st

ic

s

A

ge

(

65

-7

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-86-320.jpg)

![ye

ar

s)

0.

29

[

0.

45

]

0.

29

[

0.

46

]

0.

24

[

0.

43

]

0.

25

[](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-87-320.jpg)

![0.

43

]

0.

38

[

0.

49

]

0.

39

[

0.

49

]

0.

26

[

0.

44

]

A

ge](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-88-320.jpg)

![(

75

-8

5

ye

ar

s)

0.

30

[

0.

46

]

0.

28

[

0.

45

]

0.

36

[

0.

48](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-89-320.jpg)

![]

0.

31

[

0.

46

]

0.

35

[

0.

48

]

0.

28

[

0.

45

]

0.

27

[

0.

44](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-90-320.jpg)

![]

A

ge

(

≥8

5

ye

ar

s)

0.

20

[

0.

40

]

0.

19

[

0.

39

]

0.

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-91-320.jpg)

![[

0.

47

]

0.

25

[

0.

43

]

0.

17

[

0.

38

]

0.

09

[

0.

29

]

0.

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-92-320.jpg)

![[

0.

37

]

Fe

m

al

e

0.

55

[

0.

50

]

0.

41

[

0.

49

]

0.

49

[](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-93-320.jpg)

![0.

50

]

0.

53

[

0.

50

]

0.

57

[

0.

49

]

0.

61

[

0.

49

]

0.

60

[](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-94-320.jpg)

![0.

49

]

R

ac

e

W

hi

te

0.

78

[

0.

41

]

0.

78

[

0.

42

]

0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-95-320.jpg)

![74

[

0.

44

]

0.

77

[

0.

42

]

0.

81

[

0.

39

]

0.

86

[

0.

35

]

0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-96-320.jpg)

![76

[

0.

43

]

B

la

ck

0.

09

[

0.

28

]

0.

07

[

0.

26

]

0.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-97-320.jpg)

![[

0.

33

]

0.

09

[

0.

29

]

0.

07

[

0.

25

]

0.

06

[

0.

23

]

0.

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-98-320.jpg)

![[

0.

30

]

H

is

pa

ni

c

0.

10

[

0.

30

]

0.

10

[

0.

30

]

0.

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-99-320.jpg)

![[

0.

30

]

0.

11

[

0.

31

]

0.

11

[

0.

31

]

0.

06

[

0.

24

]

0.

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-100-320.jpg)

![[

0.

31

]

O

th

er

r

ac

e

0.

03

[

0.

18

]

0.

04

[

0.

21

]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-101-320.jpg)

![0.

03

[

0.

17

]

0.

03

[

0.

18

]

0.

01

[

0.

12

]

0.

03

[

0.

16

]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-102-320.jpg)

![0.

04

[

0.

19

]

M

ed

ia

n

ho

us

eh

o

ld

in

co

m

e

Q

ua

rt](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-103-320.jpg)

![ile

1

0.

34

[

0.

47

]

0.

34

[

0.

47

]

0.

37

[

0.

48

]

0.

35

[

0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-104-320.jpg)

![48

]

0.

40

[

0.

49

]

0.

28

[

0.

45

]

0.

33

[

0.

47

]

Q

ua

rt](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-105-320.jpg)

![ile

2

0.

33

[

0.

47

]

0.

33

[

0.

47

]

0.

33

[

0.

47

]

0.

33

[

0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-106-320.jpg)

![47

]

0.

33

[

0.

47

]

0.

34

[

0.

47

]

0.

33

[

0.

47

]

Q

ua](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-107-320.jpg)

![rt

ile

3

0.

24

[

0.

42

]

0.

23

[

0.

42

]

0.

22

[

0.

41

]

0.

23

[](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-108-320.jpg)

![0.

42

]

0.

21

[

0.

41

]

0.

27

[

0.

44

]

0.

24

[

0.

43

]

Q

ua](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-109-320.jpg)

![rt

ile

4

0.

09

[

0.

29

]

0.

09

[

0.

29

]

0.

08

[

0.

26

]

0.

09

[](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-110-320.jpg)

![0.

28

]

0.

06

[

0.

24

]

0.

11

[

0.

32

]

0.

09

[

0.

29

]

Li

vi](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-111-320.jpg)

![ng

lo

ca

ti

o

n

R

ur

al

a

re

a

0.

06

[

0.

23

]

0.

06

[

0.

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-112-320.jpg)

![]

0.

06

[

0.

23

]

0.

06

[

0.

23

]

0.

08

[

0.

28

]

0.

06

[

0.

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-113-320.jpg)

![]

0.

05

[

0.

22

]

U

rb

an

a

re

a

0.

94

[

0.

23

]

0.

94

[](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-114-320.jpg)

![0.

24

]

0.

94

[

0.

23

]

0.

94

[

0.

23

]

0.

92

[

0.

28

]

0.

94

[](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-115-320.jpg)

![0.

24

]

0.

95

[

0.

22

]

Pr

im

ar

y

pa

ye

r

Fe

e

fo

r

se

rv](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-116-320.jpg)

![ic

e

0.

54

[

0.

50

]

0.

49

[

0.

50

]

0.

66

[

0.

47

]

0.

59

[

0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-117-320.jpg)

![49

]

0.

62

[

0.

49

]

0.

52

[

0.

50

]

0.

46

[

0.

50

]

M

ed

ic](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-118-320.jpg)

![ar

e

A

dv

an

ta

ge

0.

22

[

0.

41

]

0.

24

[

0.

43

]

0.

25

[

0.

43](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-119-320.jpg)

![]

0.

19

[

0.

39

]

0.

26

[

0.

44

]

0.

20

[

0.

40

]

0.

21

[

0.

41](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-120-320.jpg)

![]

Pr

iv

at

e

in

su

ra

nc

e

0.

24

[

0.

43

]

0.

27

[

0.

44

]

0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-121-320.jpg)

![09

[

0.

29

]

0.

22

[

0.

41

]

0.

12

[

0.

32

]

0.

28

[

0.

45

]

0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-122-320.jpg)

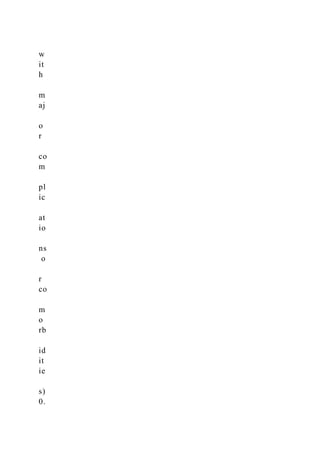

![33

[

0.

47

]

T

o

ta

l n

um

be

r

o

f

co

m

o

rb

id

it

ie

s

2.

92

[](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-123-320.jpg)

![1.

89

]

2.

77

[

1.

78

]

3.

56

[

1.

79

]

3.

55

[

2.

04

]

2.

83

[](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-124-320.jpg)

![1.

77

]

2.

22

[

1.

58

]

2.

72

[

1.

90

]

H

ig

h

se

ve

ri

ty

(](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-125-320.jpg)

![19

[

0.

39

]

0.

17

[

0.

38

]

0.

30

[

0.

46

]

0.

26

[

0.

44

]

0.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-127-320.jpg)

![32

[

0.

47

]

0.

05

[

0.

22

]

0.

15

[

0.

36

]

N

95

1,

21

5

10](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/nursingresearchreadingusingandcreatingevidence-221201194343-37b865eb/85/NURSING-RESEARCHREADING-USING-AND-CREATING-EVIDENCE-docx-128-320.jpg)