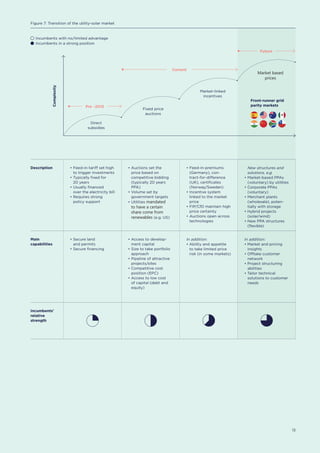

This document analyzes the rapid growth and cost-competitiveness of utility-scale solar energy, highlighting significant opportunities for energy incumbents in the sector. It emphasizes the transition from traditional energy sources as solar capacity continues to expand, particularly in leading markets like China, India, and the US. Despite the potential, the document notes that many existing energy companies are still hesitant to invest in solar technologies, primarily relying on partnerships with solar developers instead.