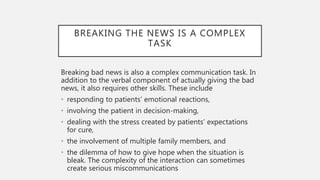

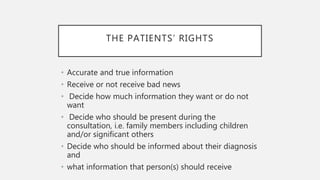

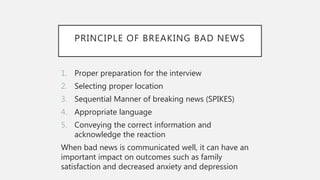

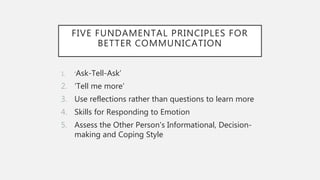

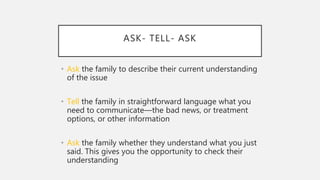

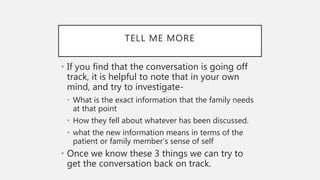

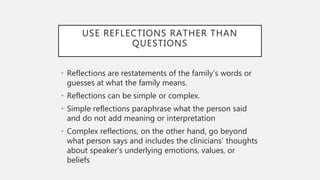

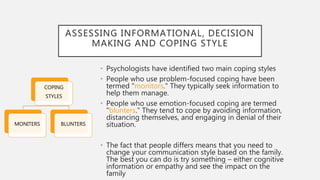

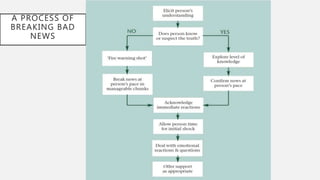

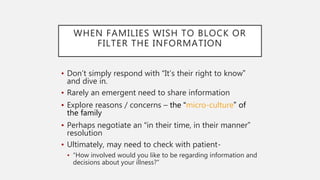

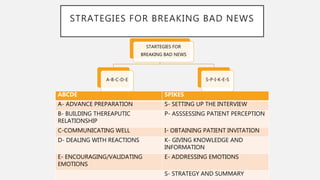

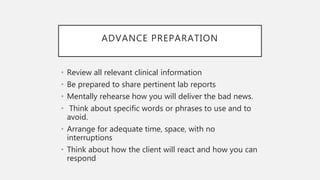

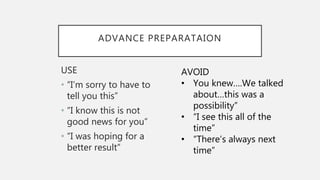

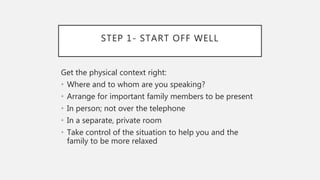

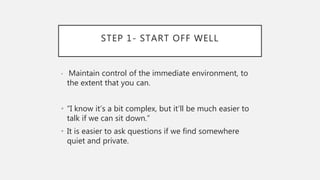

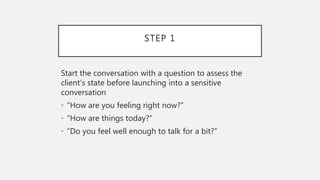

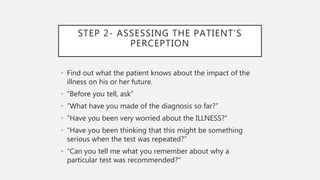

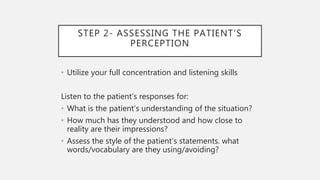

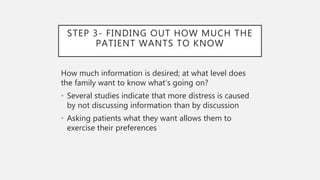

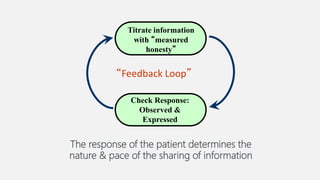

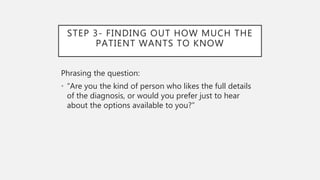

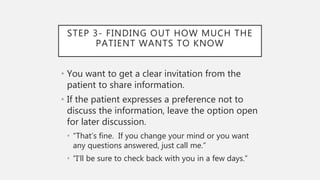

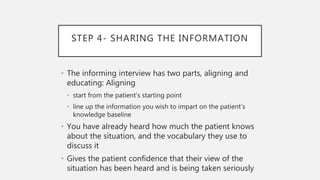

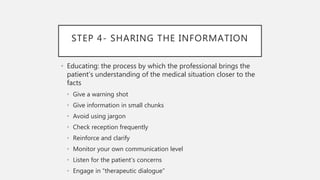

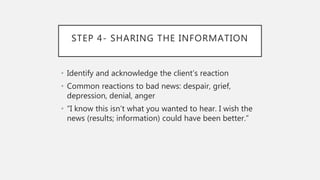

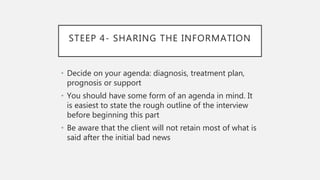

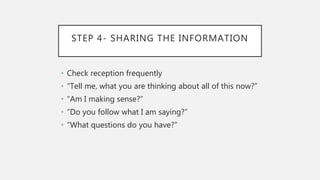

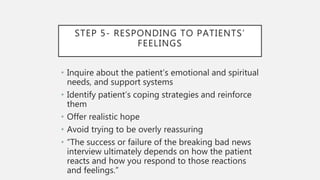

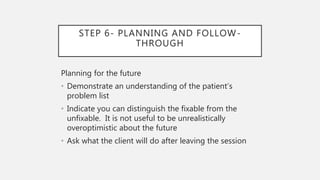

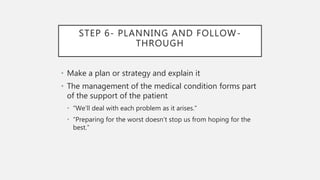

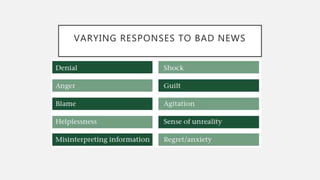

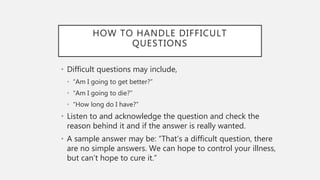

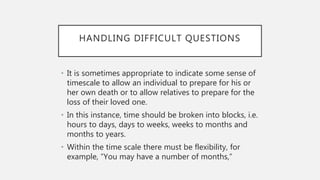

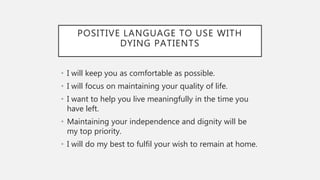

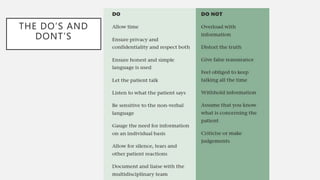

The document provides guidance on breaking critical or bad news to patients. It discusses that breaking bad news is a complex task that requires skills like assessing the patient's understanding, gauging how much information they want, sharing the news in a stepwise manner, responding to emotions, and planning follow up. The document outlines a six step protocol for breaking bad news, including preparing, assessing the patient's perspective, determining how much they want to know, sharing the information, responding to reactions, and planning next steps.