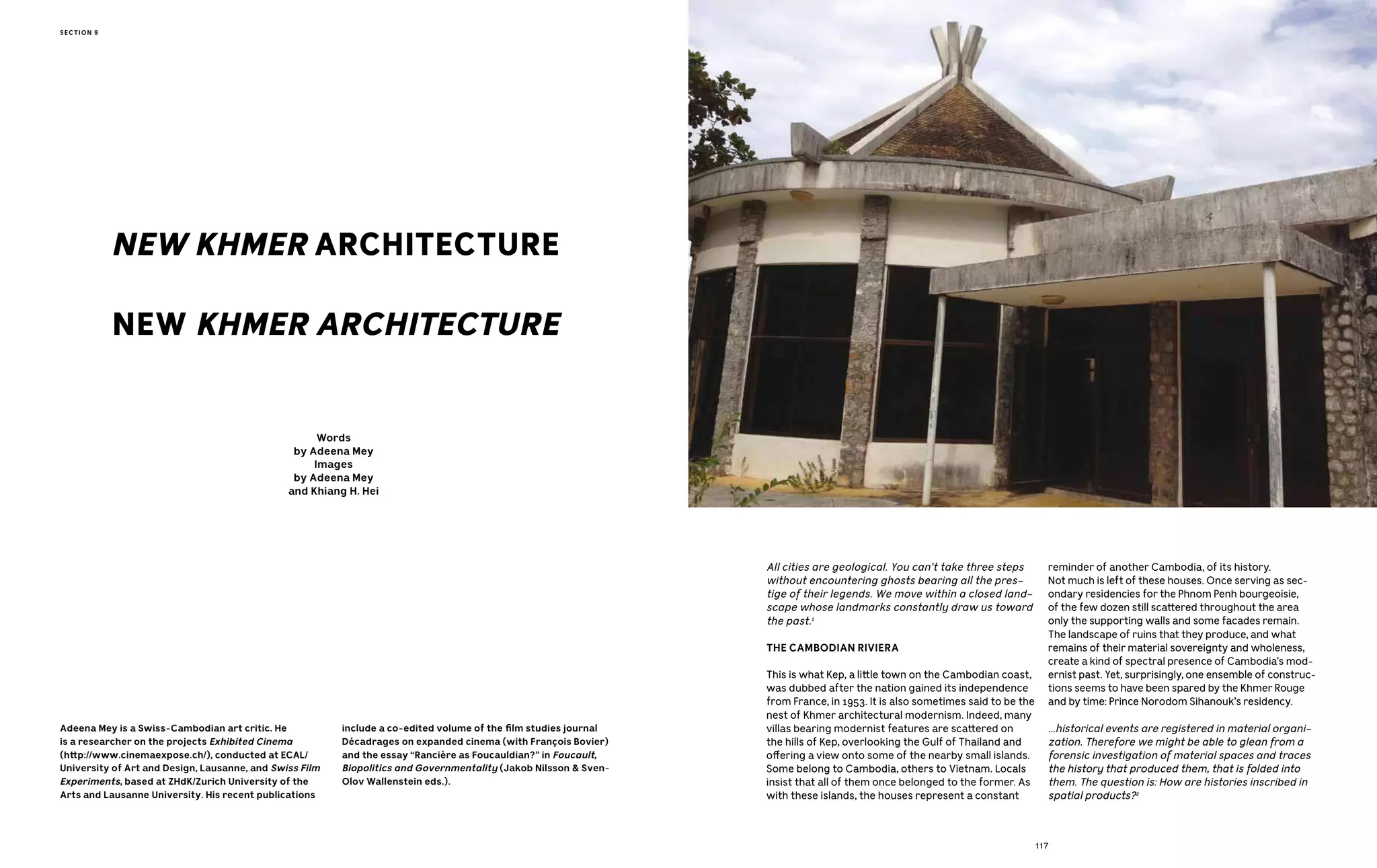

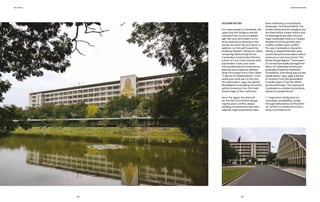

This section summarizes the development of New Khmer Architecture in Cambodia during the 1960s. It describes how modernist architectural styles emerged under Prince Norodom Sihanouk's Sangkum regime as a way to modernize Cambodia while maintaining Khmer cultural influences. Key architects like Vann Molyvann designed buildings that incorporated modern concrete structures with references to traditional Khmer forms like pagodas. Many significant government and university buildings were constructed during this period, which represented a "golden age" of Cambodian arts and culture. However, most New Khmer Architecture was later destroyed during the Khmer Rouge regime, with only ruins remaining. The section explores how the modernist past is remembered nostalgically today and questions

![A NEW REPORTAGE

CAMBODIA, FROM THE FUTURE

In the emerging Cambodian cul-

tural scene, there is a 1960s retro

trend, not to mention a nostalgia for

this recent but almost extirpated

past. The productions of the New

Khmer Architects stand as physi-

cal witnesses to this “golden age.”

They atest to an “authentic” Khmer

identity, against the fast rise of Asian

turbo-capitalism and its glass tow-

ers. Remember, save, patrimonialize.

But beyond nostalgia or reaction,

and indiference, can what is left of

the New Khmer Architecture be re-

invested with any sense of futurity?

SECTION 9

notes

1. Gilles Ivain [Ivan Chtcheglov], Formulary for a New Urbanism, Situationist International, No. 1, October 1953.

2. Eyal Weizman, “Political Plastic (Interview)”, Collapse. Philosophical Research and Development, Vol. VI, 2010.

3. Kenneth Frampton, Towards A Critical Regionalism: Six Points for an Architecture of Resistance, in Hal Foster,The Anti-Aesthetic. Essays on Postmodern

Culture, 1983.

4. Peter Eisenman, Graves of Modernism, Eisenman Inside Out. Selected Writings 1963-1988, 2004.

5. Wolf Vostell and Dick Higgins, Fantastic Architecture, 1969.

127

126](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/newkhmerarchitecturenewkhmerarchit-220806032216-683001cc/85/New_Khmer_Architecture_New_Khmer_Archit-pdf-6-320.jpg)