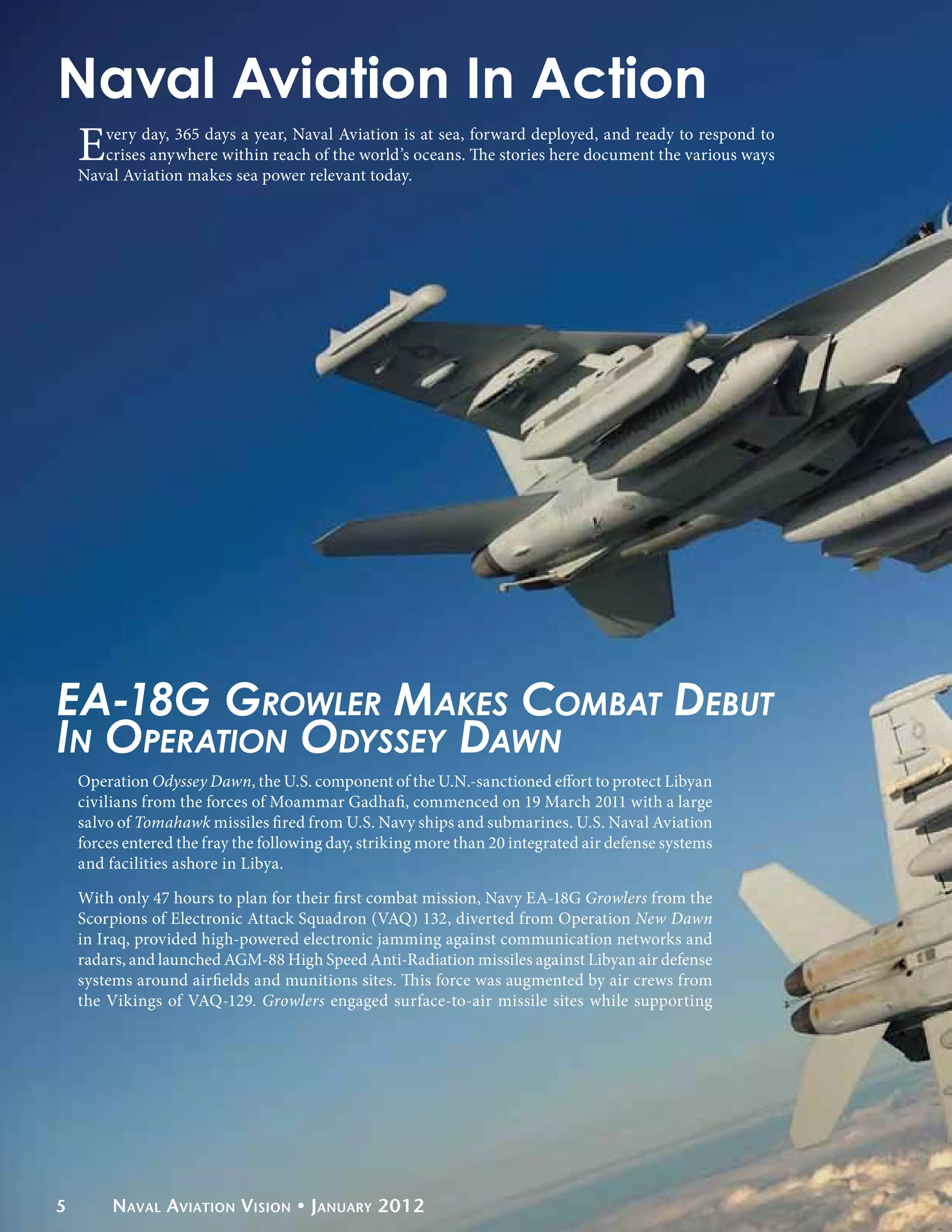

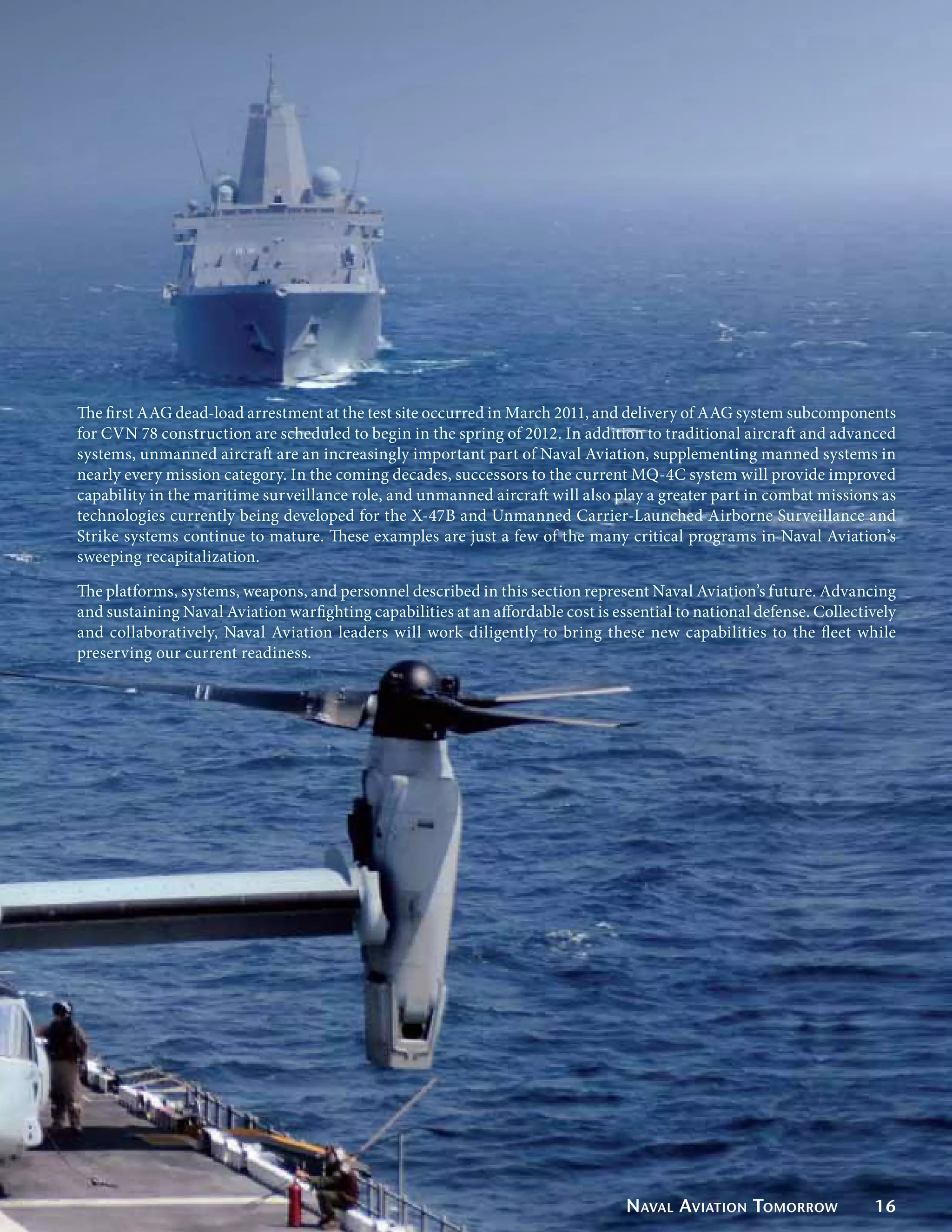

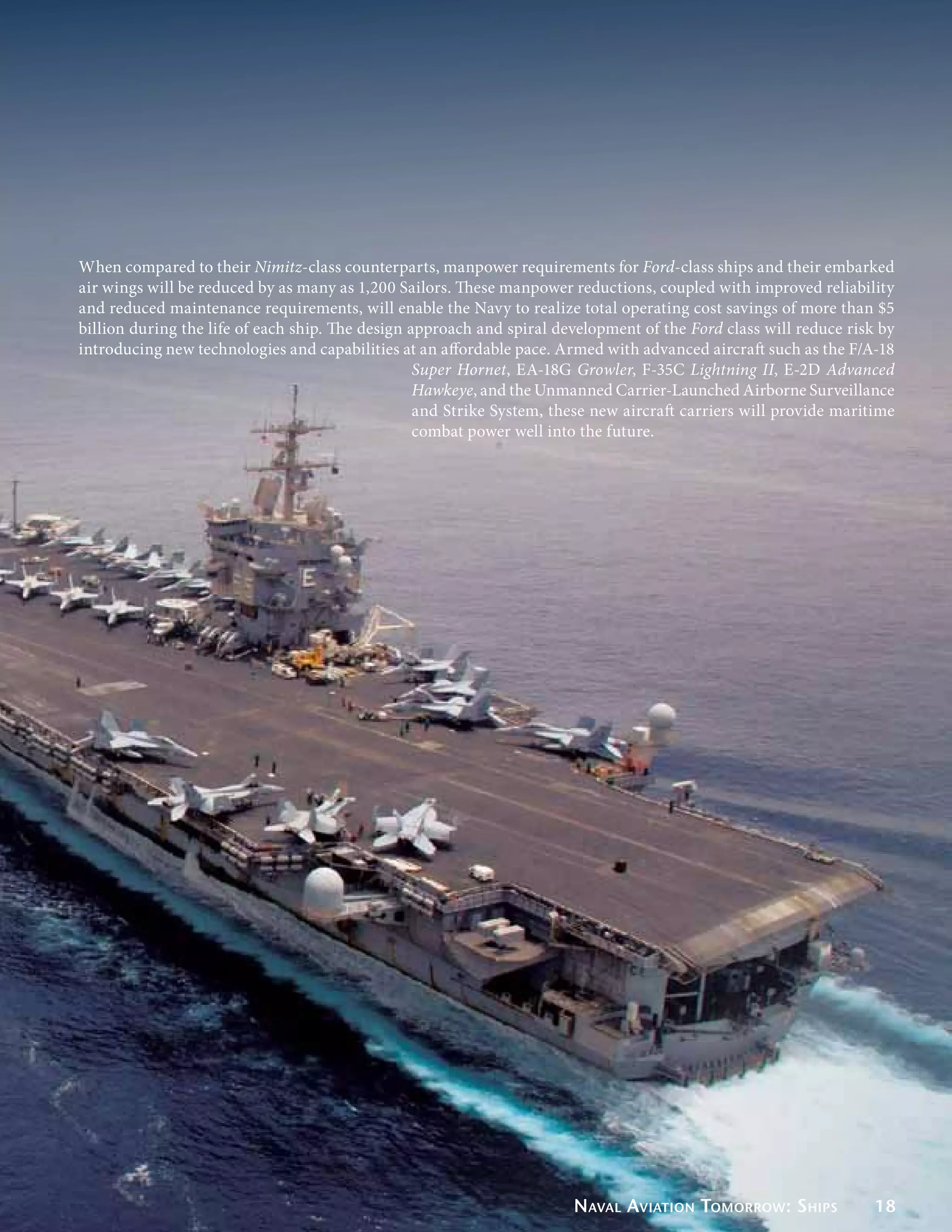

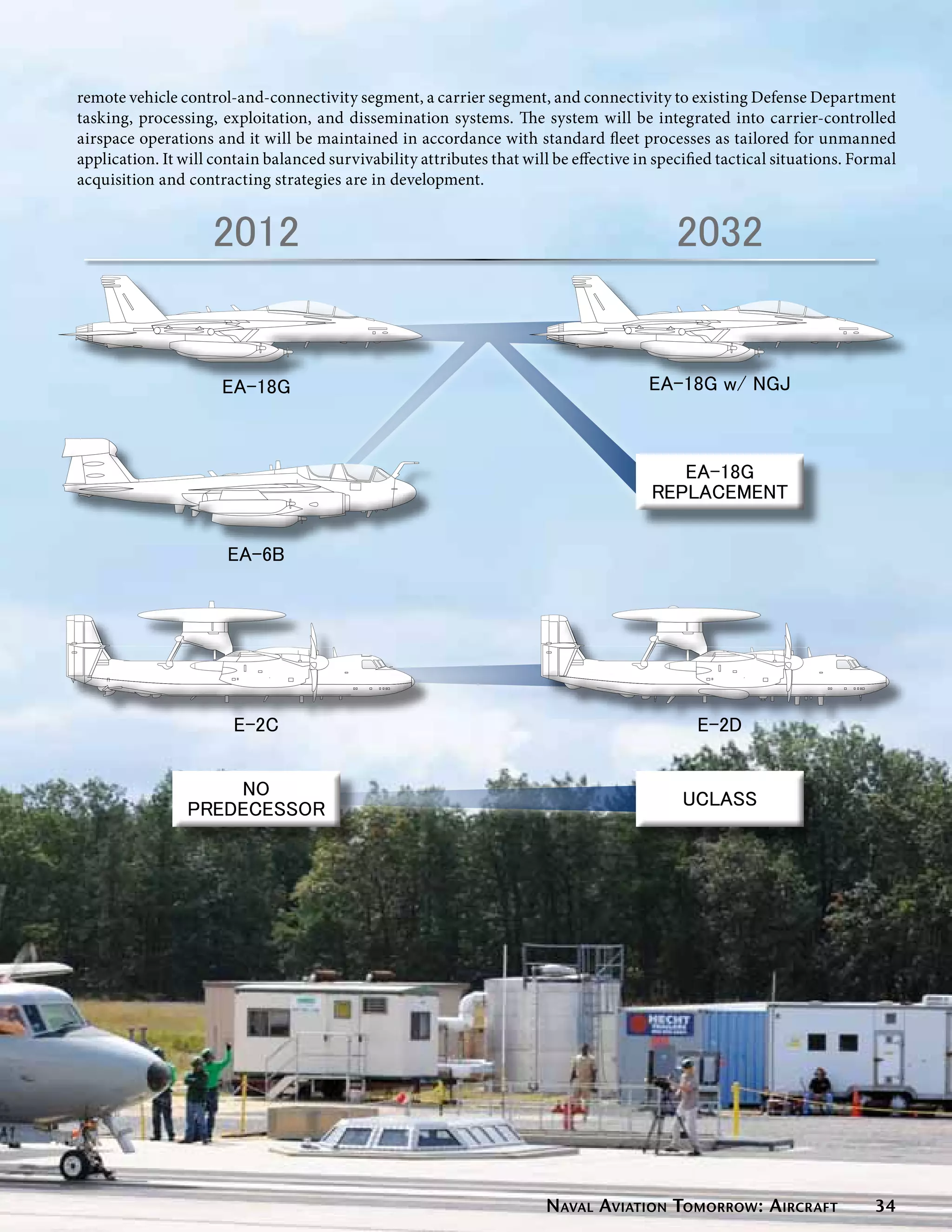

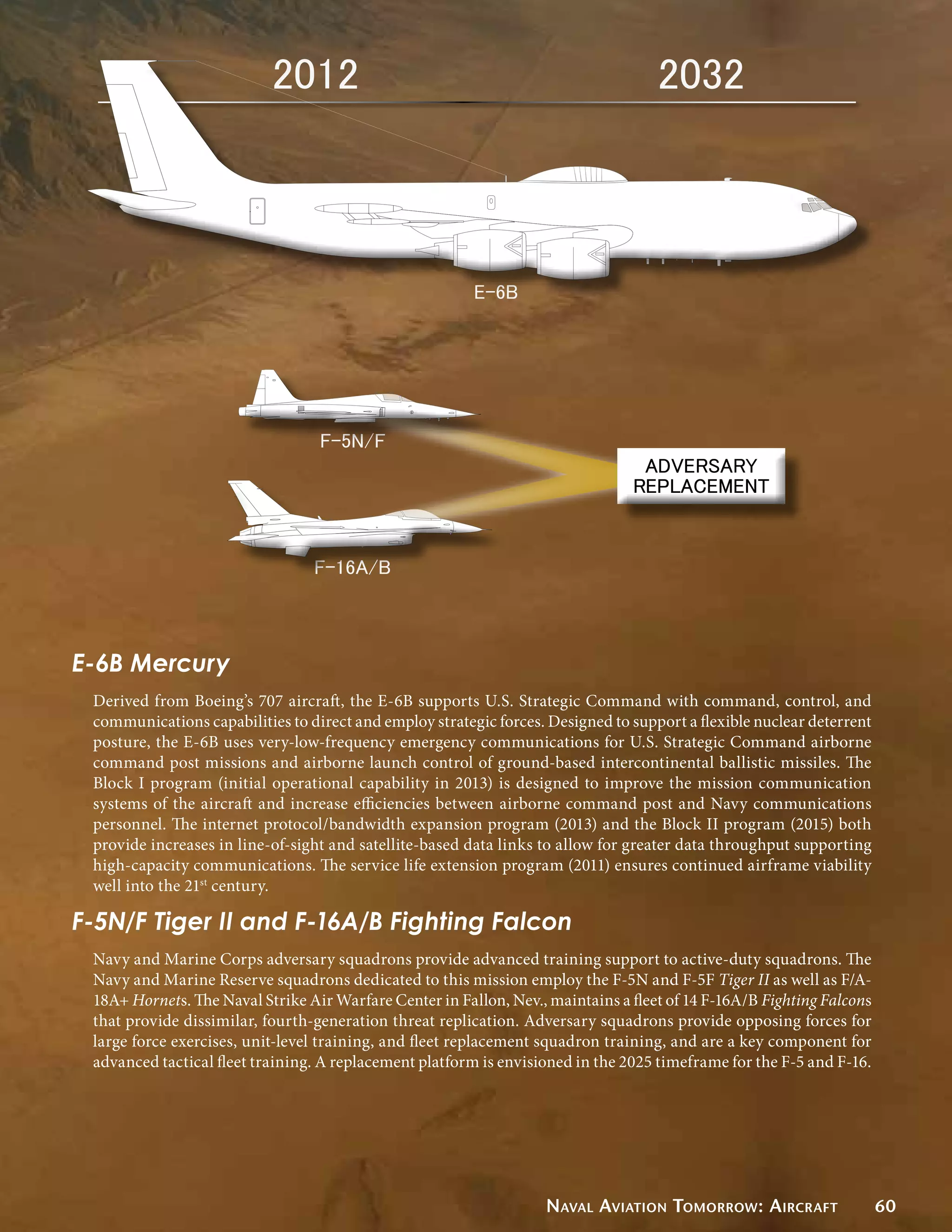

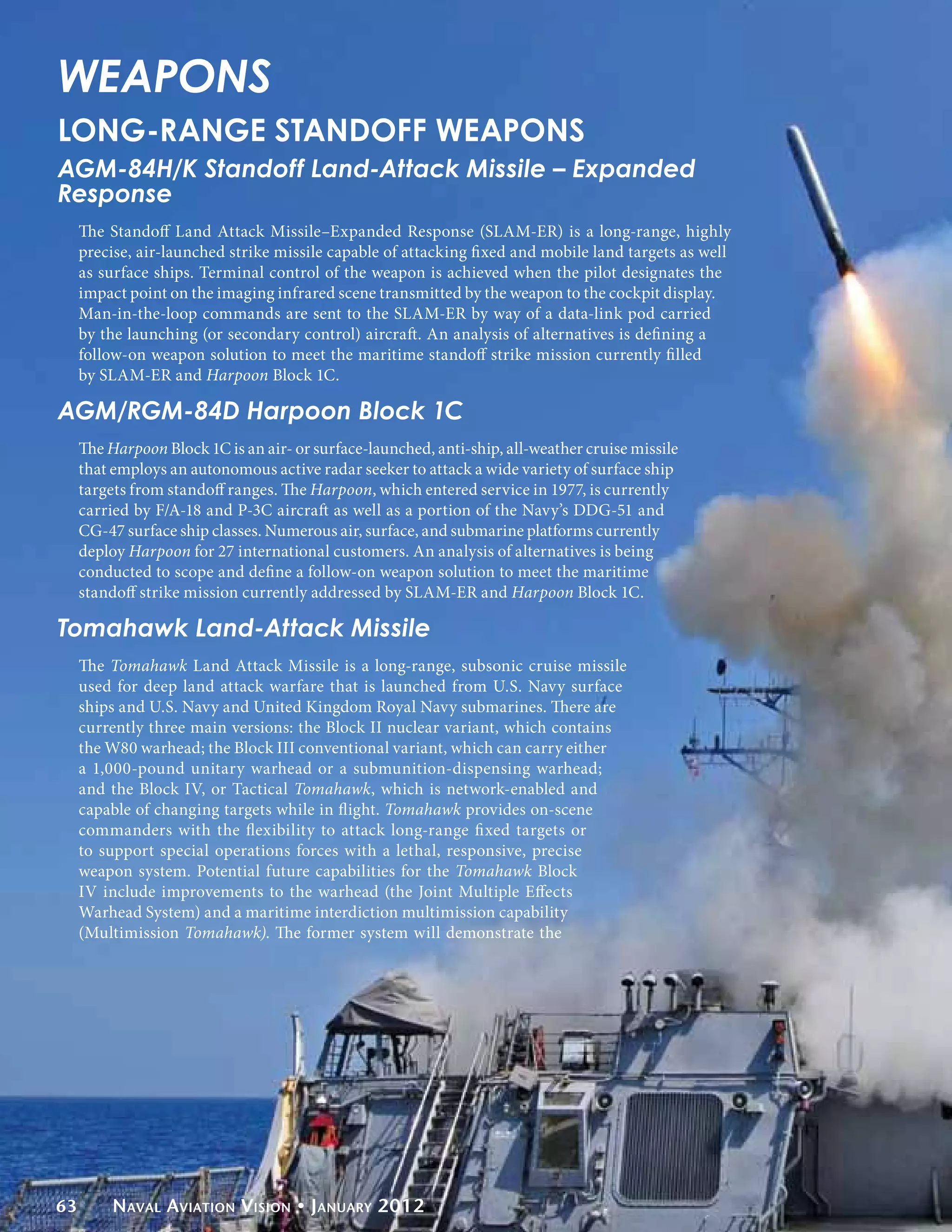

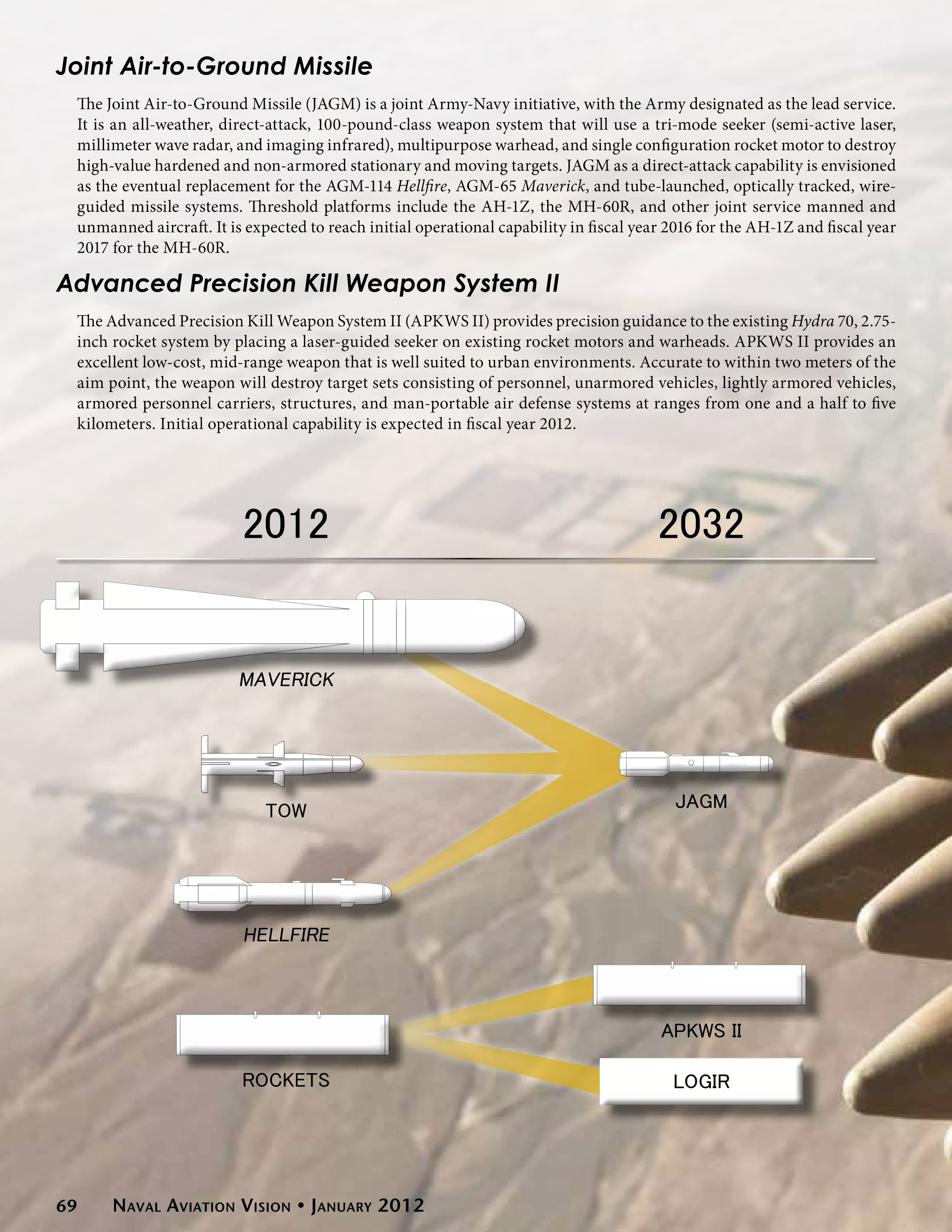

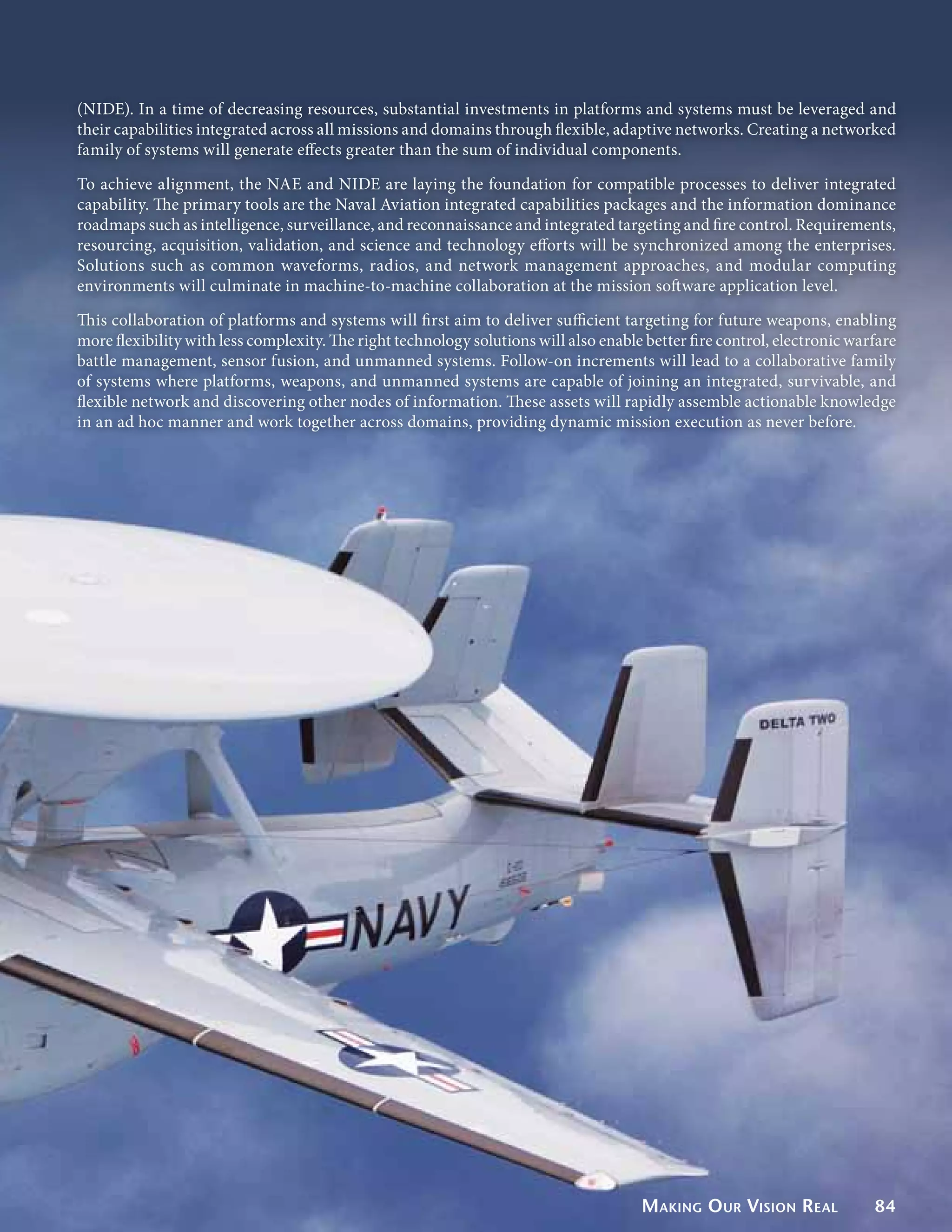

This document provides a vision for the future of Naval Aviation, outlining its capabilities and transitions over the coming years. It describes Naval Aviation's role in addressing challenges from near-peer competitors and extremism. The vision emphasizes maintaining a global reach without permanent bases through aircraft carriers and amphibious ships. It outlines roadmaps for new ships, aircraft, weapons and concepts to allow Naval Aviation to continue projecting power despite budget pressures.