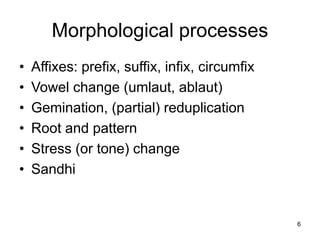

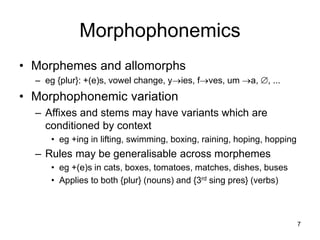

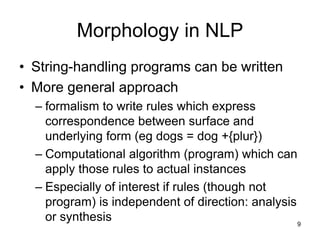

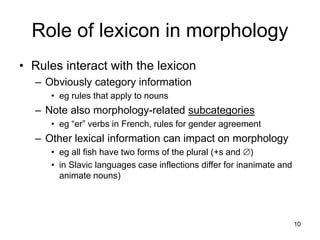

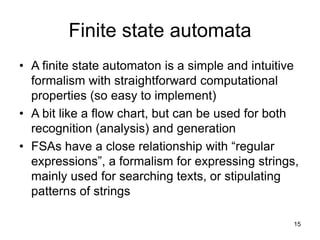

This document provides an overview of morphology in computational linguistics. It discusses topics like morphemes, inflectional versus derivational morphology, and morphological processes. It also describes how morphology is handled in natural language processing, including the use of finite state automata and transducers to model morphological rules and mappings between surface forms and underlying representations.

![Morphology

See

Harald Trost “Morphology”. Chapter 2 of R Mitkov (ed.) The

Oxford Handbook of Computational Linguistics, Oxford

(2004): OUP

D Jurafsky & JH Martin: Speech and Language Processing,

Upper Saddle River NJ (2000): Prentice Hall, Chapter 3

[quite technical]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/morphology-220922141957-c059a204/75/Morphology-ppt-1-2048.jpg)

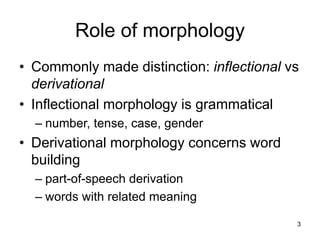

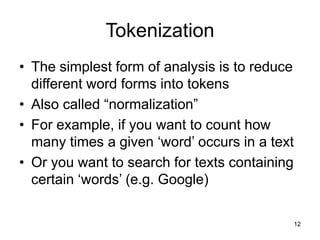

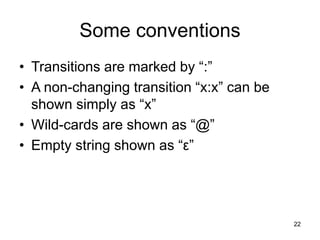

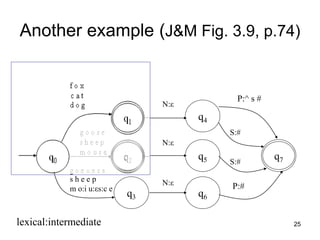

![27

q0

q6

q5

q4

q3

q2

q1

q7

g o o s e

s h e e p

m o u s e

g o:e o:e s e

s h e e p

m o:i u:εs:c e

N:ε

N:ε

N:ε

P:^ s #

S:#

S:#

P:#

[0] f:f o:o x:x [1] N:ε [4] P:^ s:s #:# [7]

[0] f:f o:o x:x [1] N:ε [4] S:# [7]

[0] c:c a:a t:t [1] N:ε [4] P:^ s:s #:# [7]

[0] s:s h:h e:e p:p [2] N:ε [5] S:# [7]

[0] g:g o:e o:e s:s e:e [3] N:ε [5] P:# [7]

f o x N P s # : f o x ^ s #

f o x N S : f o x #

c a t N P s # : c a t ^ s #

s h e e p N S : s h e e p #

g o o s e N P : g e e s e #

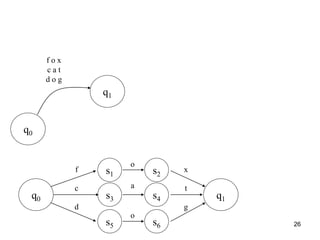

f o x

c a t

d o g](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/morphology-220922141957-c059a204/85/Morphology-ppt-27-320.jpg)

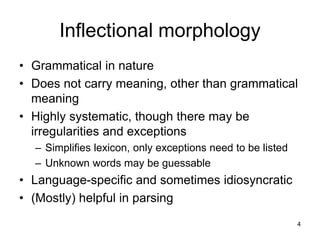

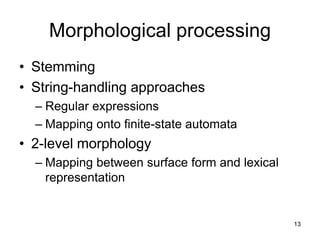

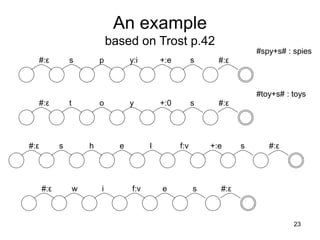

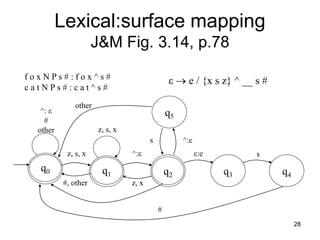

![29

f o x ^ s # f o x e s #

c a t ^ s # : c a t ^ s #

q5

q4

q0 q2 q3

q1

^: ε

#

other

other

z, s, x

z, s, x

#, other z, x

^:ε

s ^:ε

ε:e s

#

[0] f:f [0] o:o [0] x:x [1] ^:ε [2] ε:e [3] s:s [4] #:# [0]

[0] c:c [0] a:a [0] t:t [0] ^:ε [0] s:s [0] #:# [0]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/morphology-220922141957-c059a204/85/Morphology-ppt-29-320.jpg)

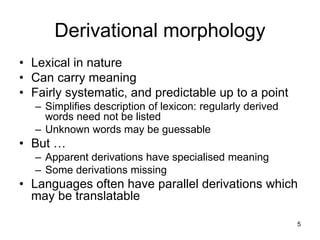

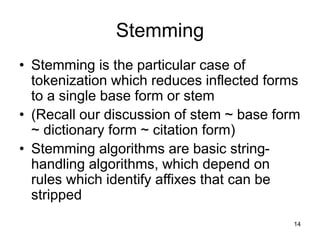

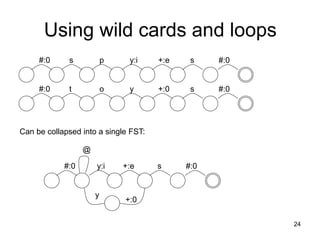

![31

FST compiler

http://www.xrce.xerox.com/competencies/content-analysis/fsCompiler/fsinput.html

[d o g N P .x. d o g s ] |

[c a t N P .x. c a t s ] |

[f o x N P .x. f o x e s ] |

[g o o s e N P .x. g e e s e]

s0: c -> s1, d -> s2, f -> s3, g -> s4.

s1: a -> s5.

s2: o -> s6.

s3: o -> s7.

s4: <o:e> -> s8.

s5: t -> s9.

s6: g -> s9.

s7: x -> s10.

s8: <o:e> -> s11.

s9: <N:s> -> s12.

s10: <N:e> -> s13.

s11: s -> s14.

s12: <P:0> -> fs15.

s13: <P:s> -> fs15.

s14: e -> s16.

fs15: (no arcs)

s16: <N:0> -> s12.

s0

s3

s2

s1

s4

c

d

f

g](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/morphology-220922141957-c059a204/85/Morphology-ppt-31-320.jpg)