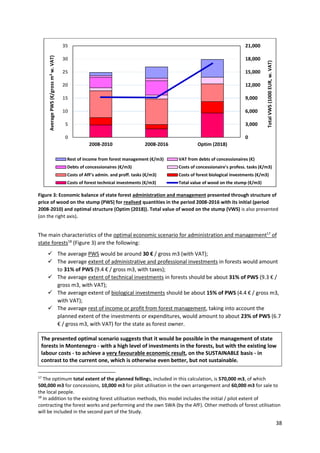

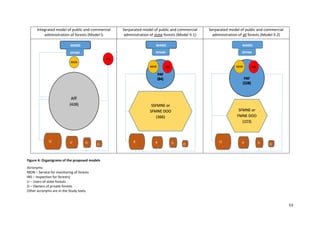

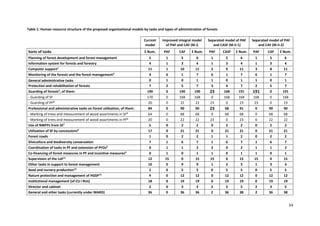

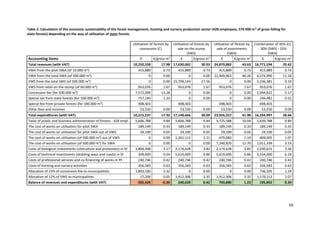

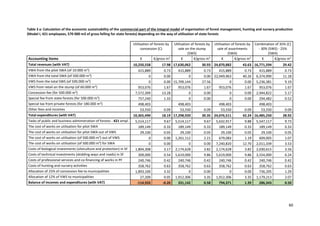

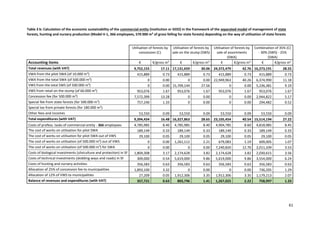

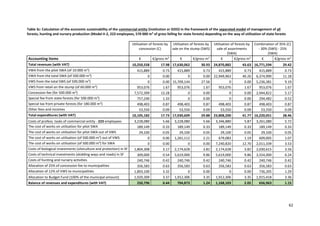

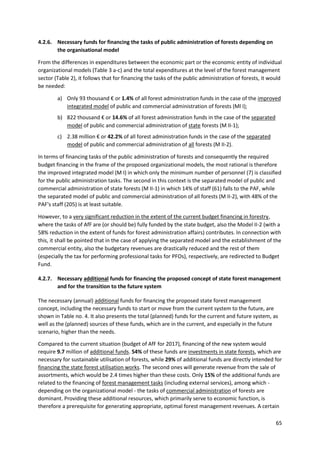

The document outlines a study on the reform of forest management and organization in Montenegro, funded by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development. It provides an analysis of the current structure and functioning of forestry-related institutions, highlights weaknesses such as inadequate staffing, training, and technological integration, and proposes improvements for sustainable forest management. Key recommendations include creating an independent forest administration, enhancing personnel qualifications, and implementing a more effective operational organization.