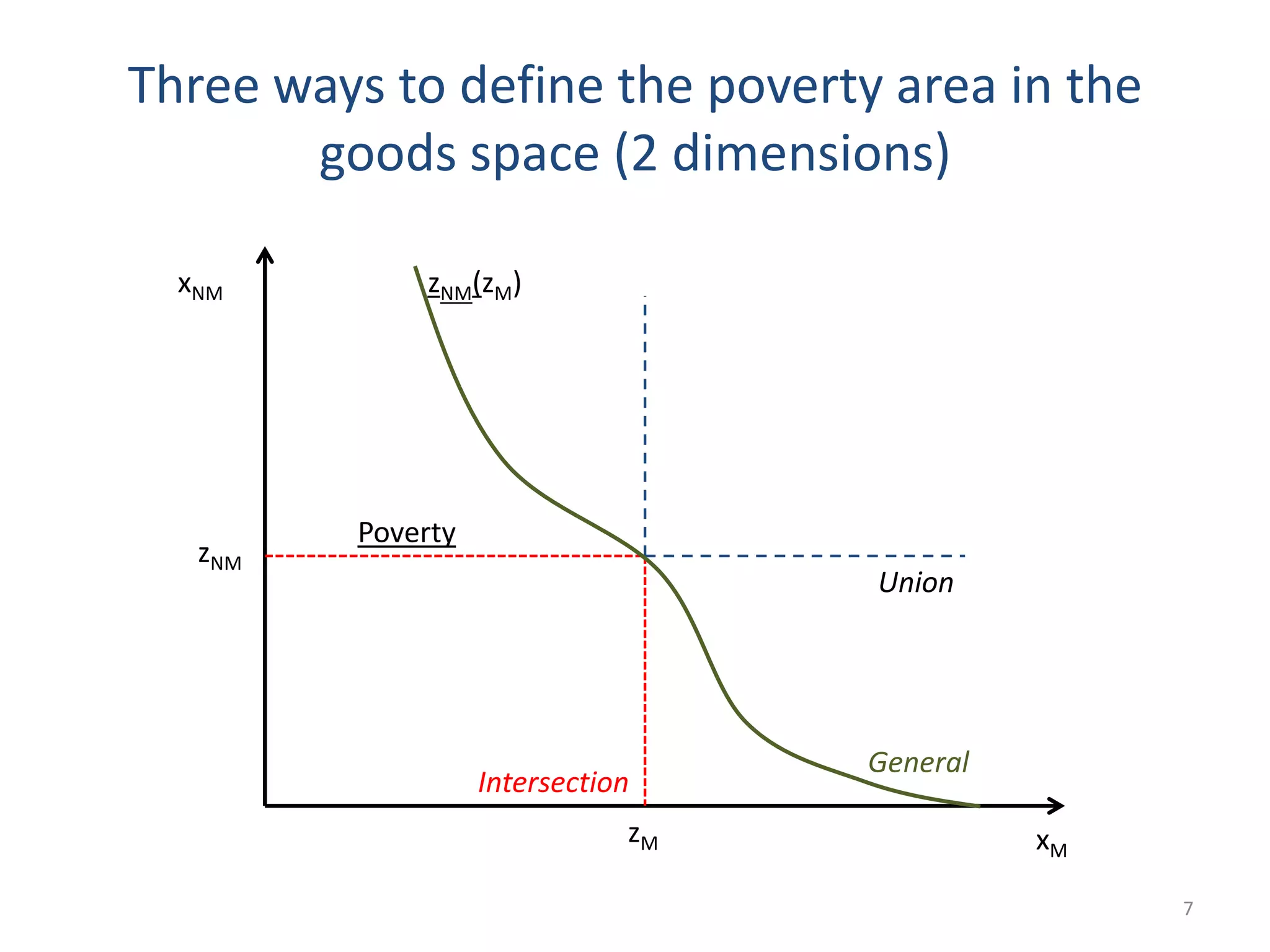

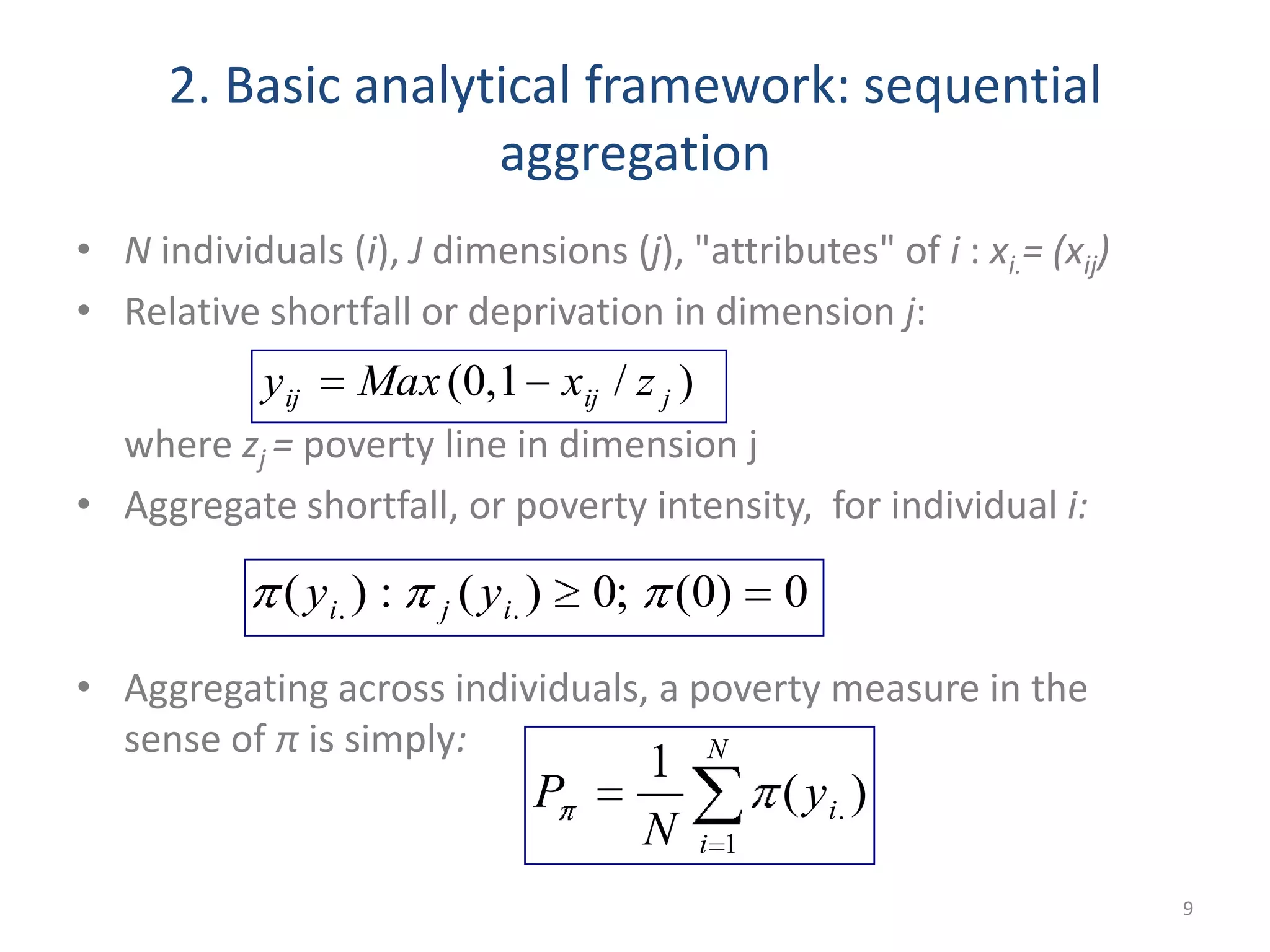

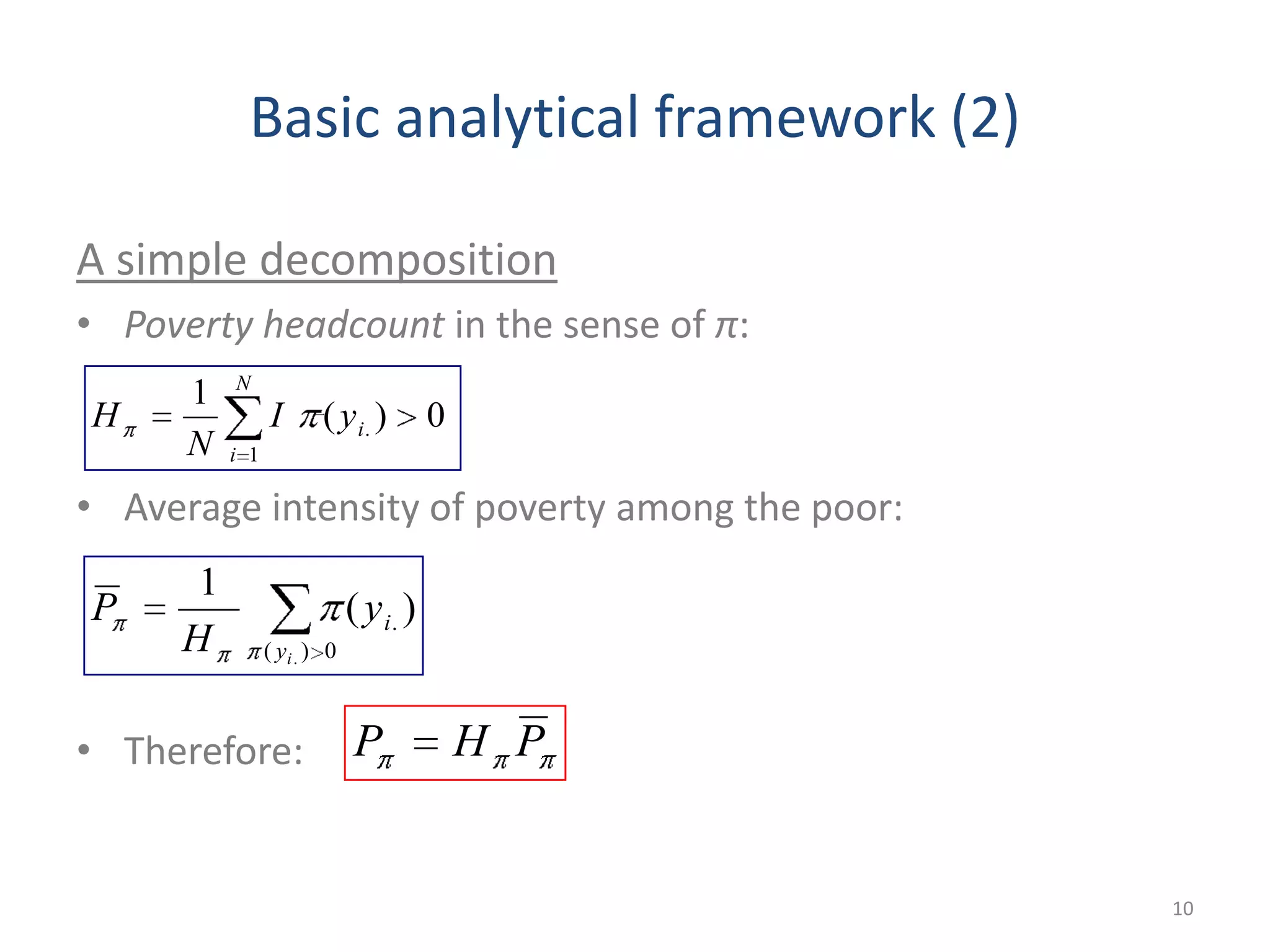

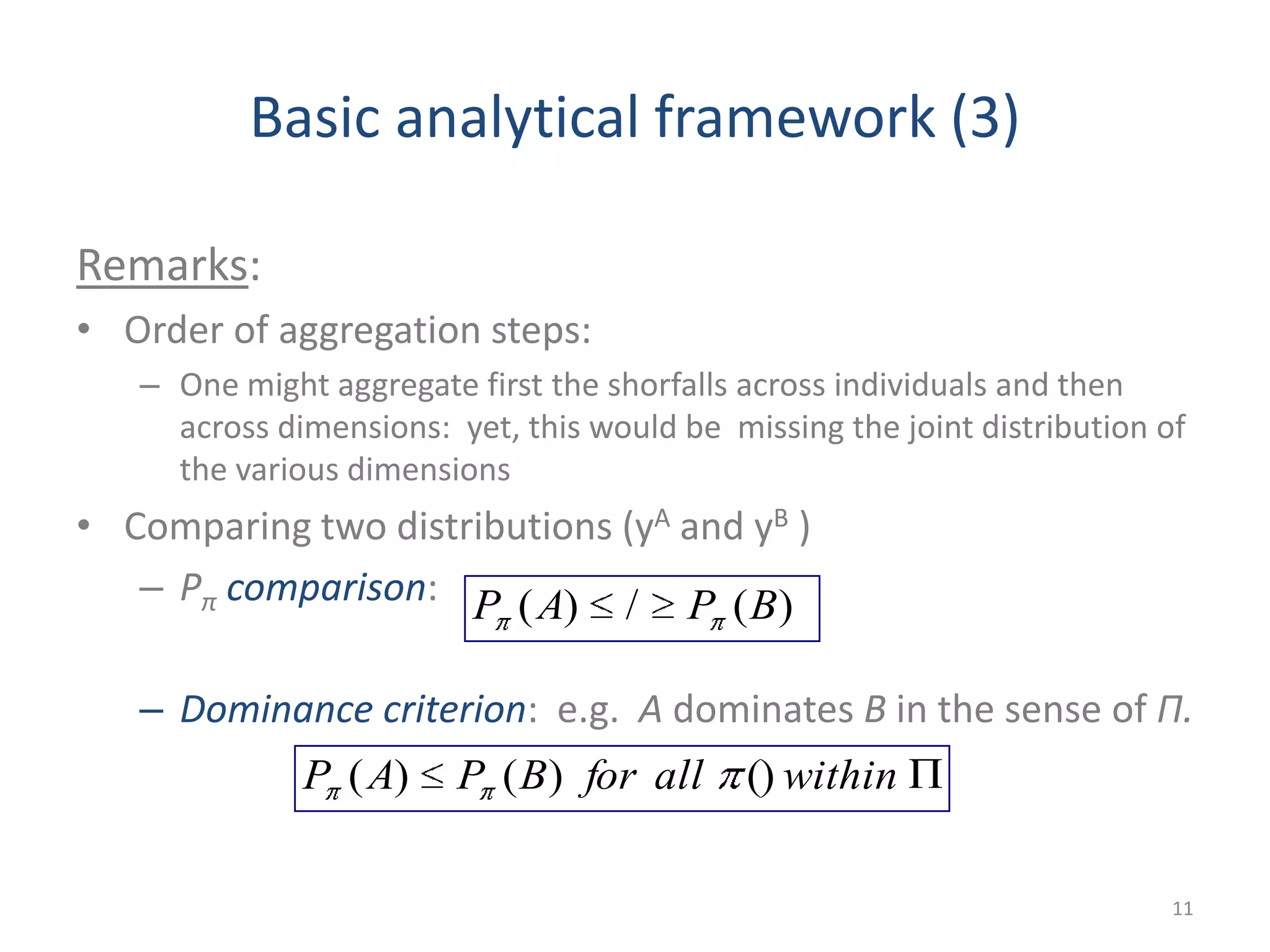

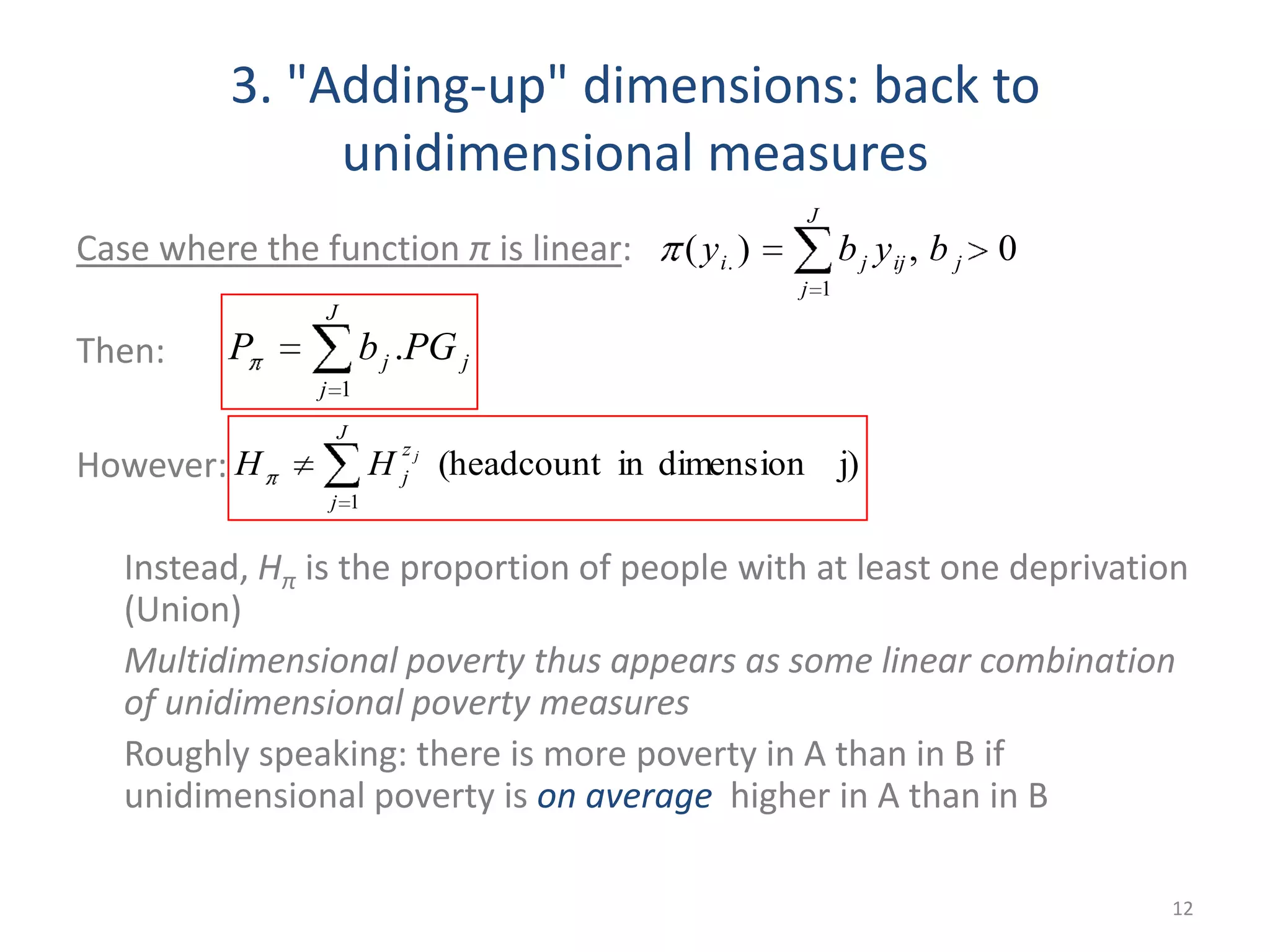

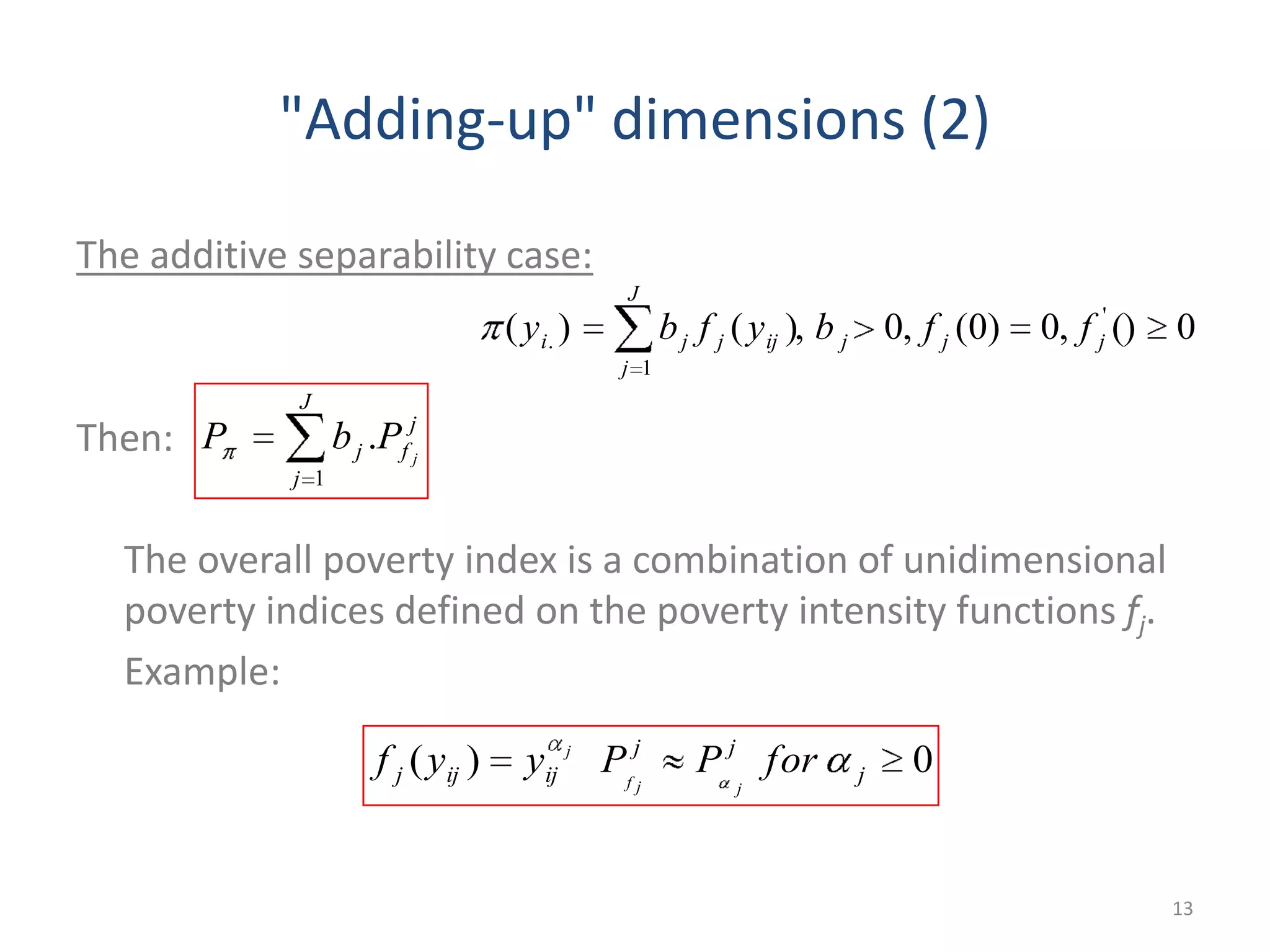

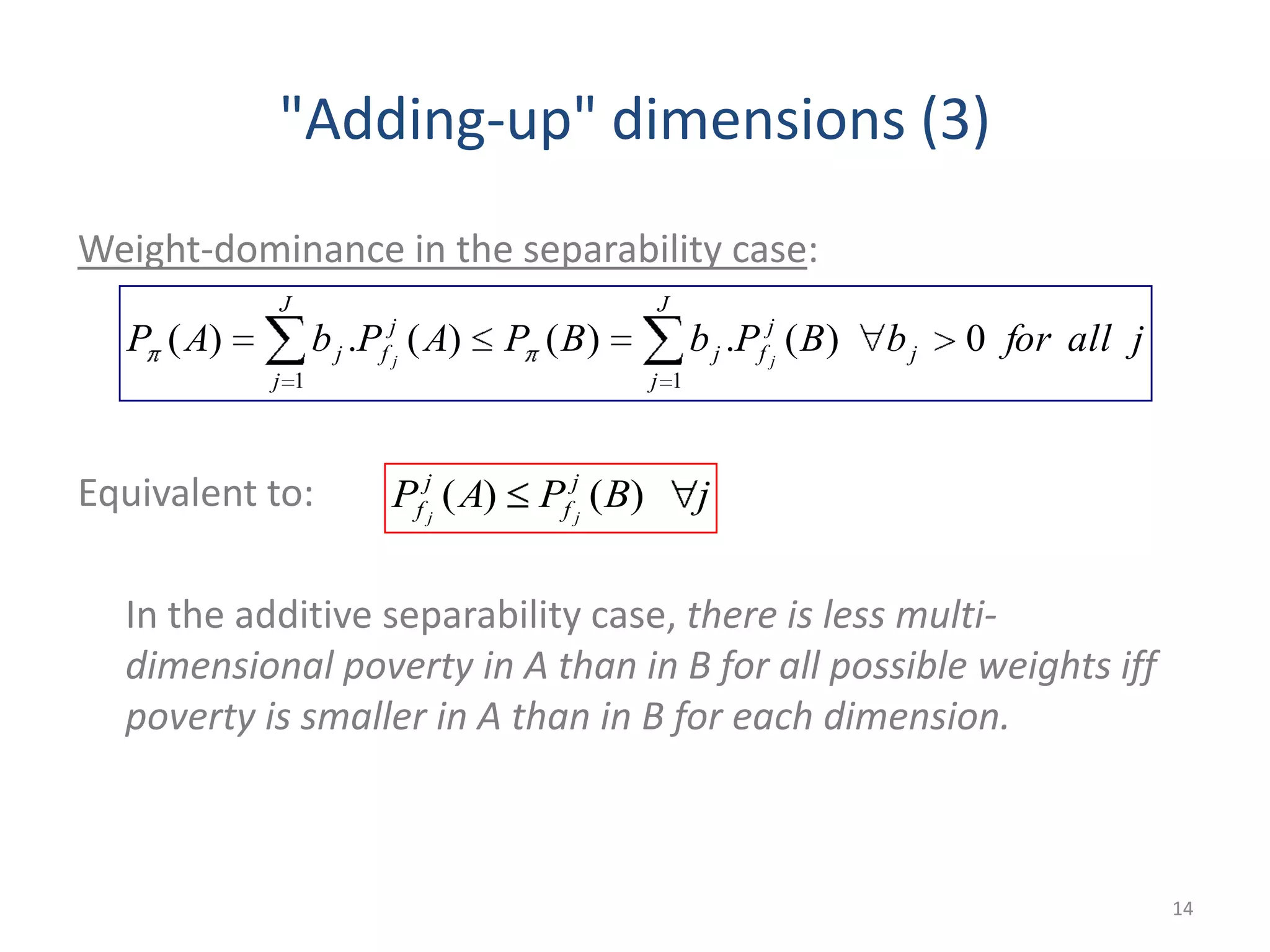

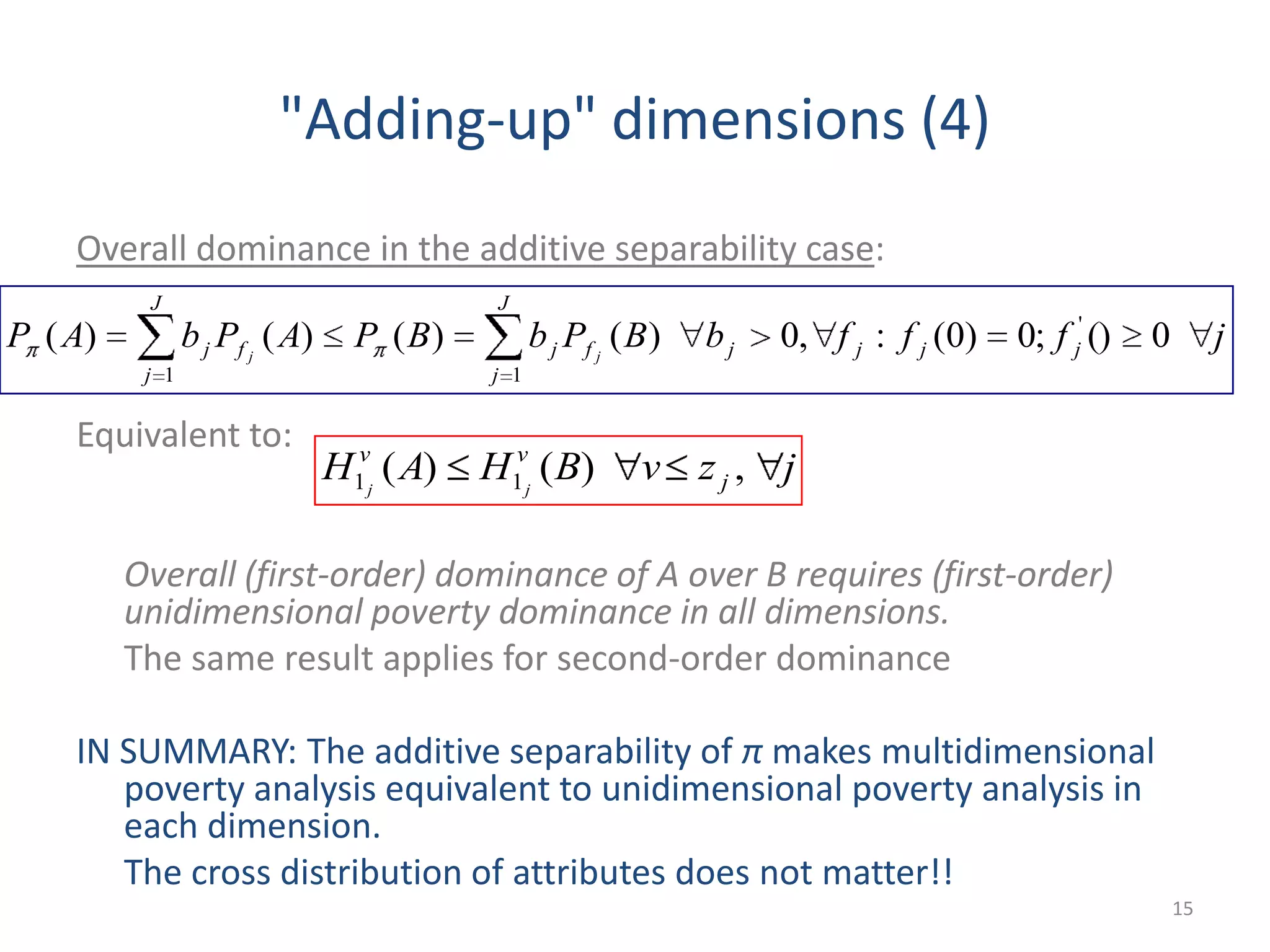

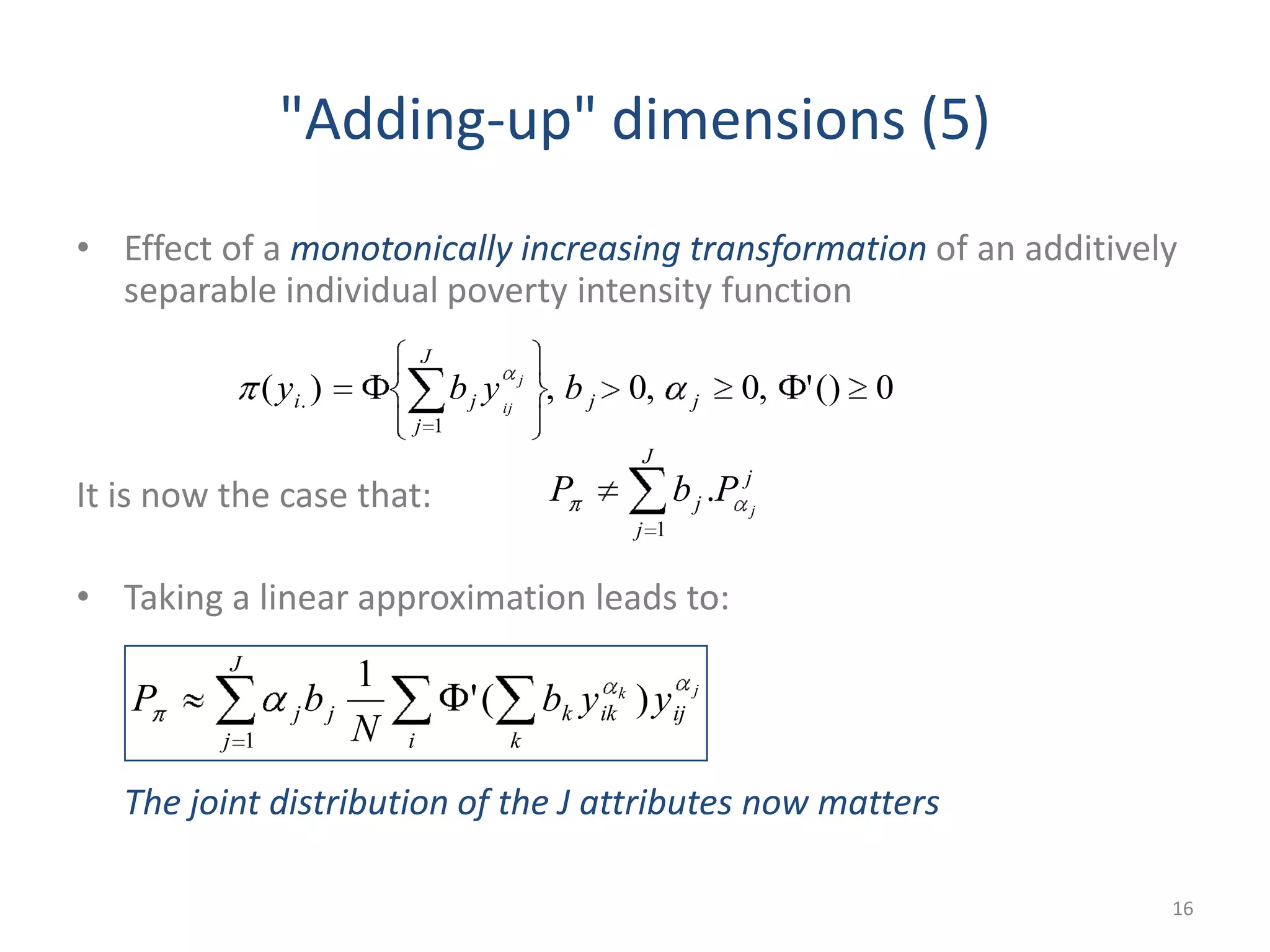

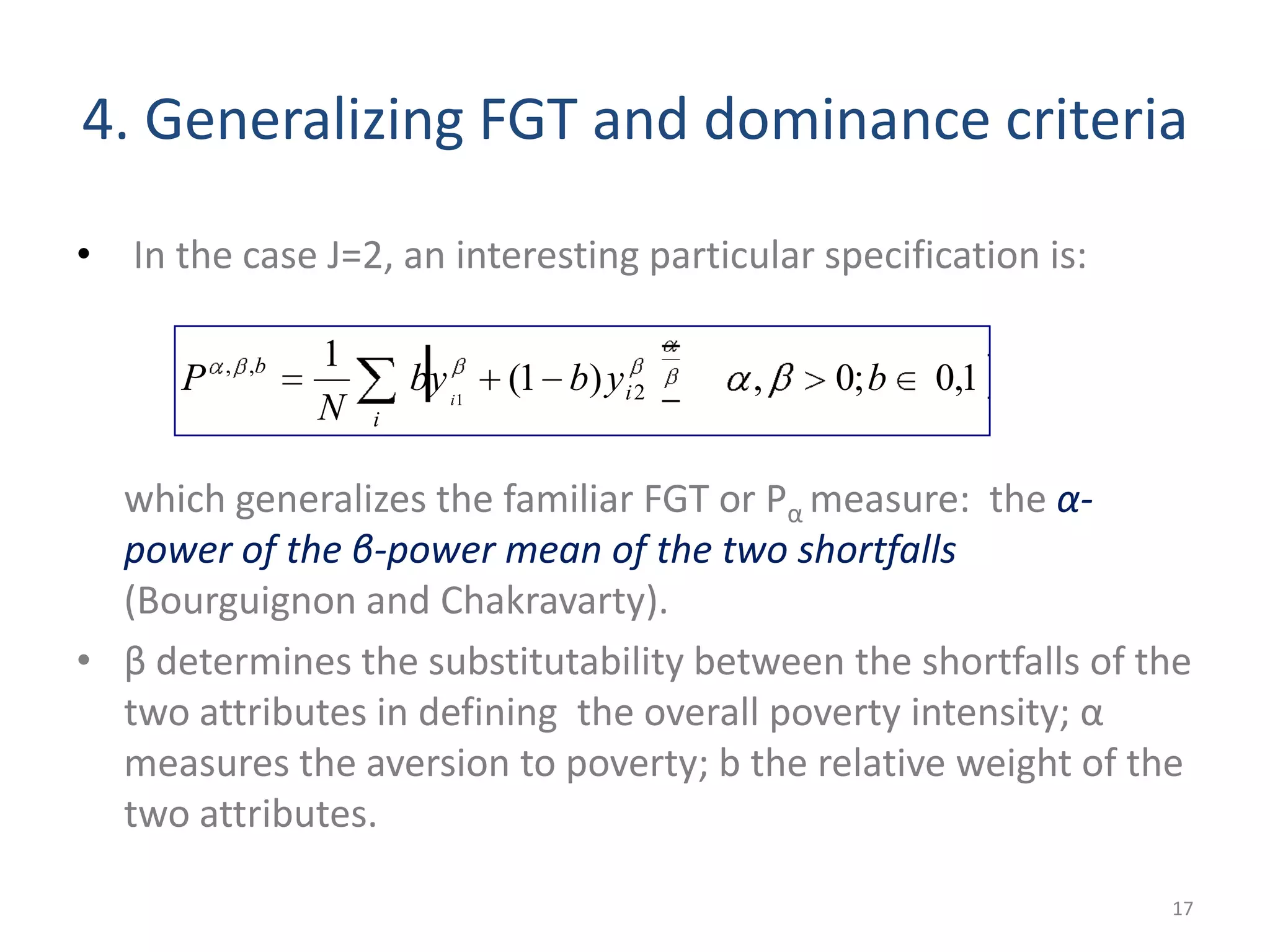

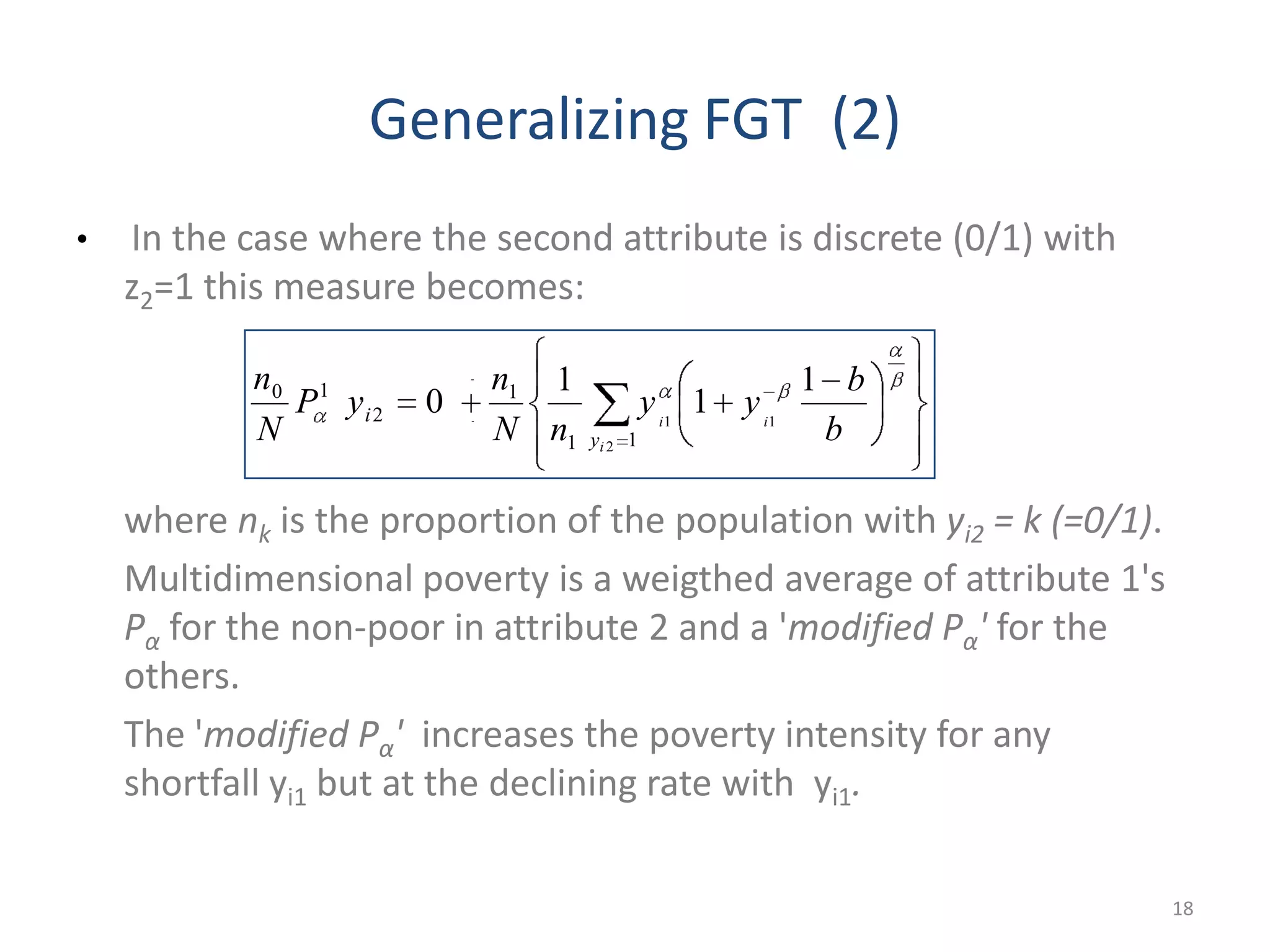

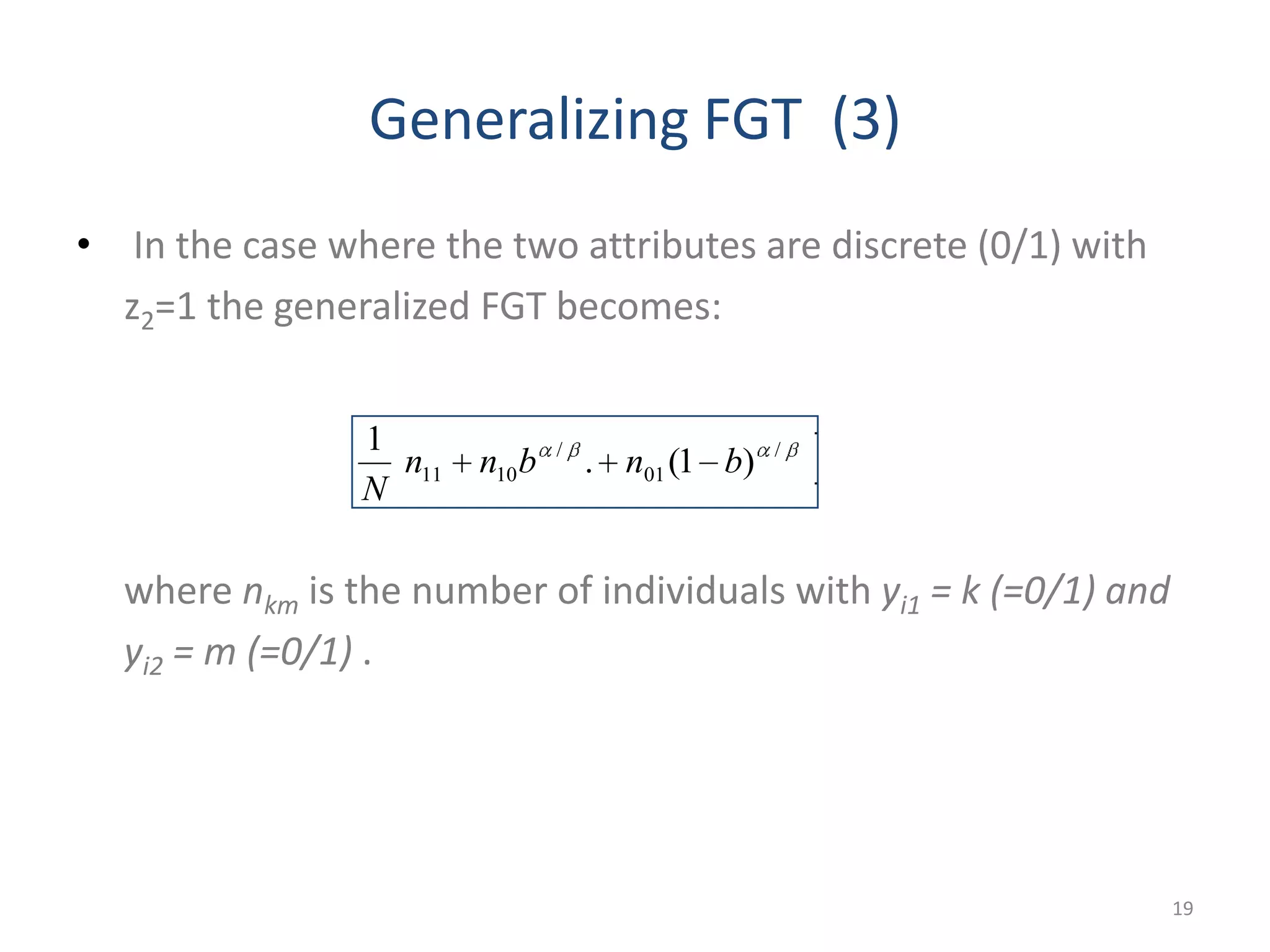

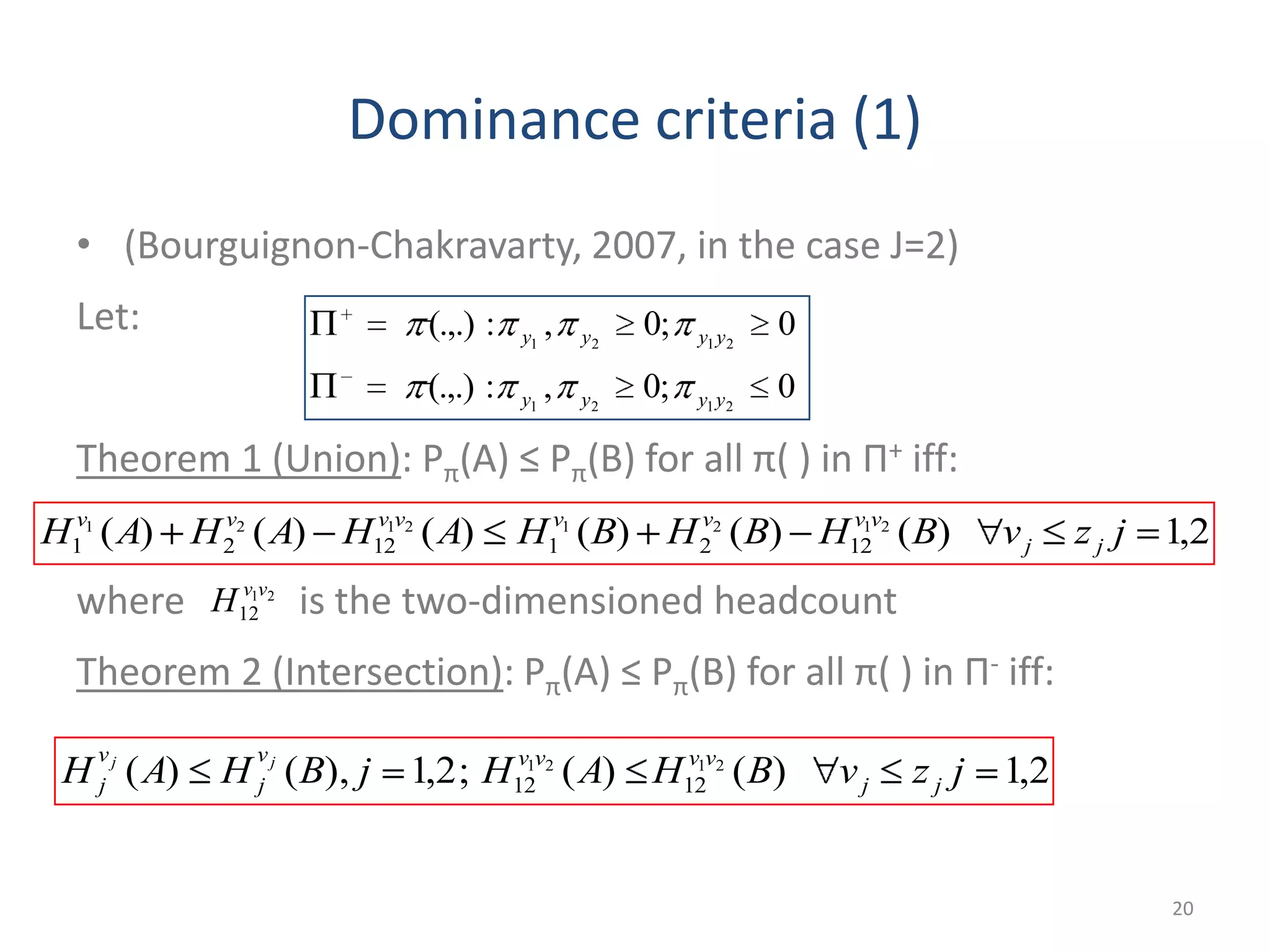

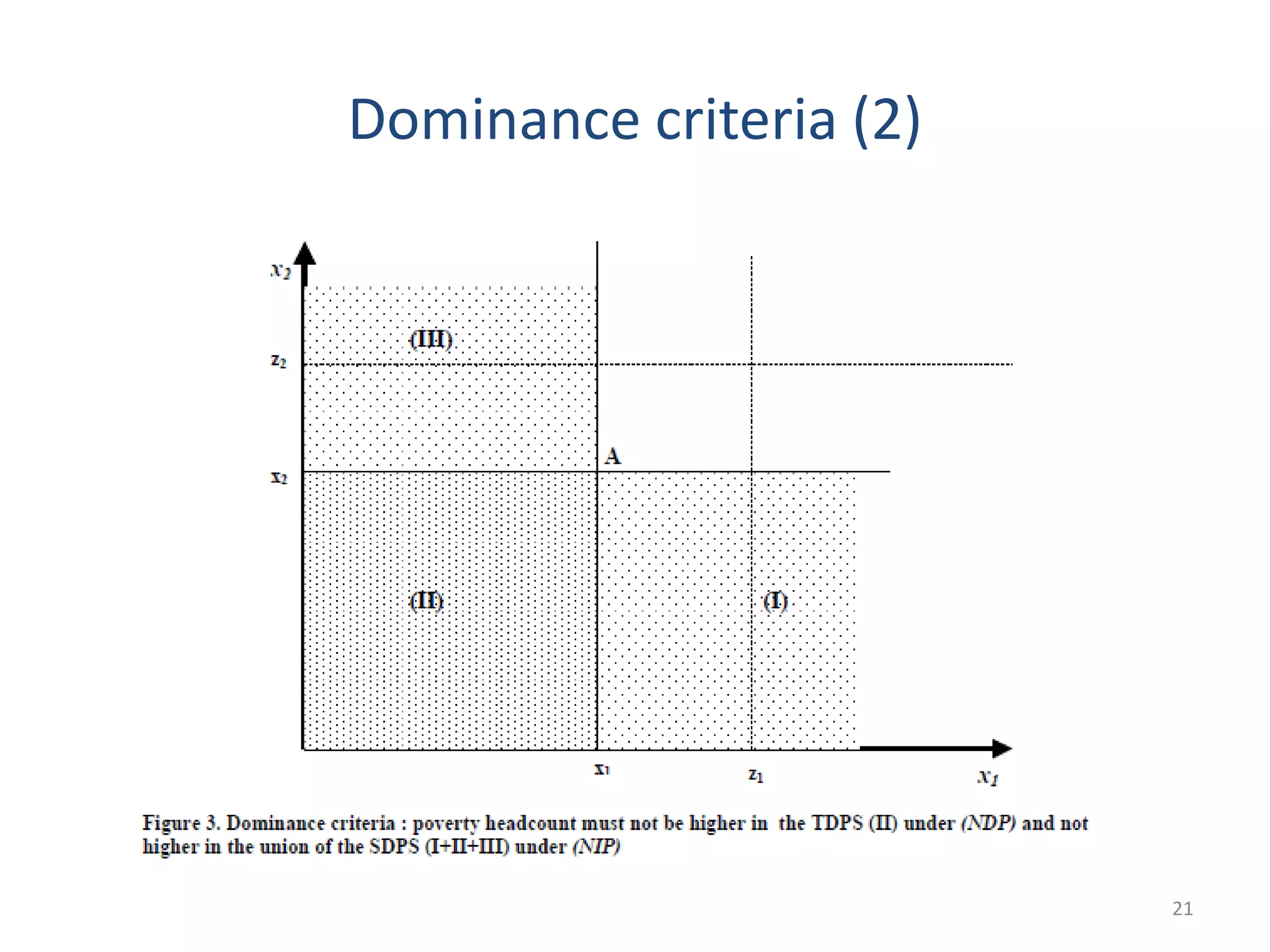

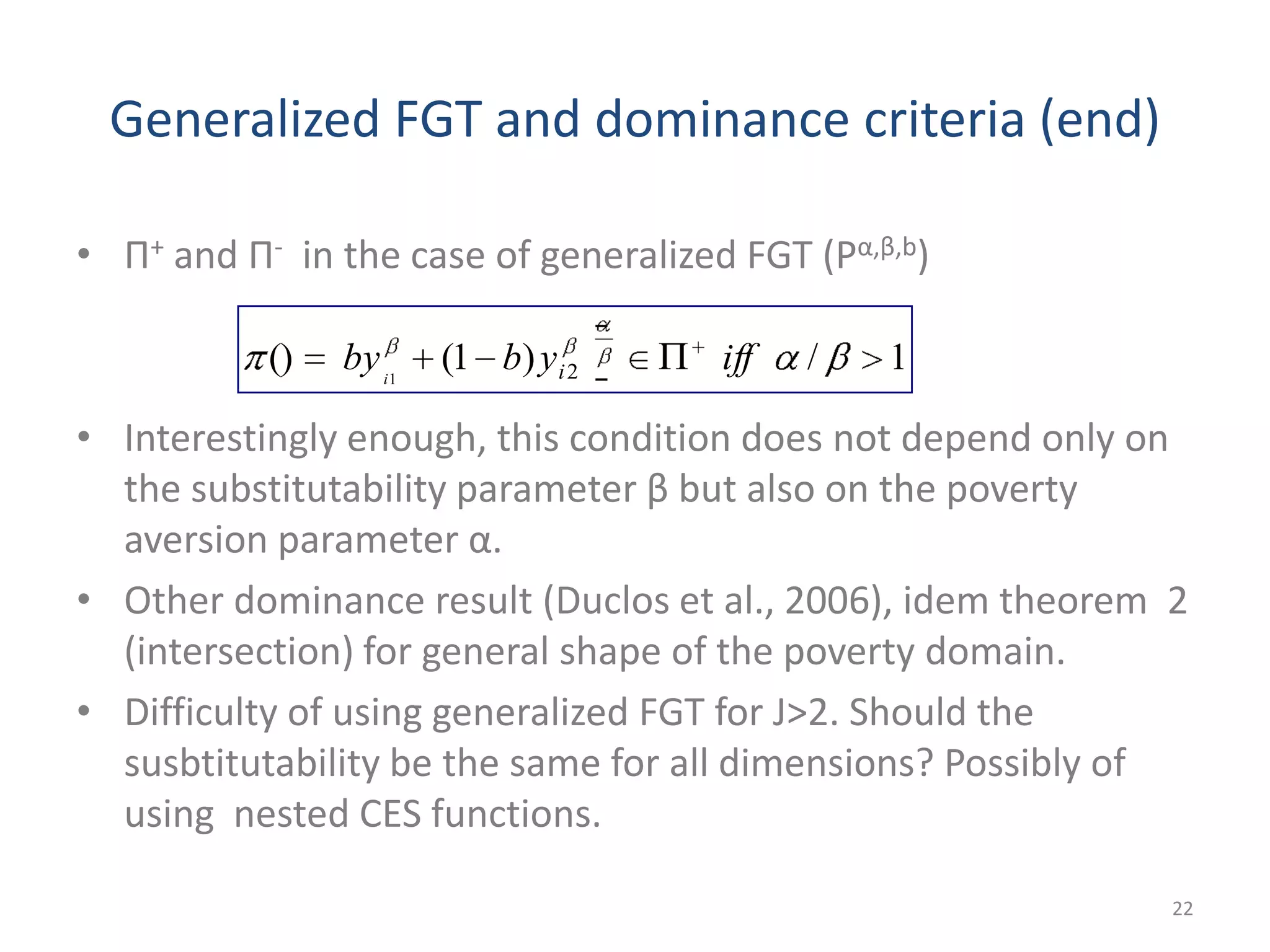

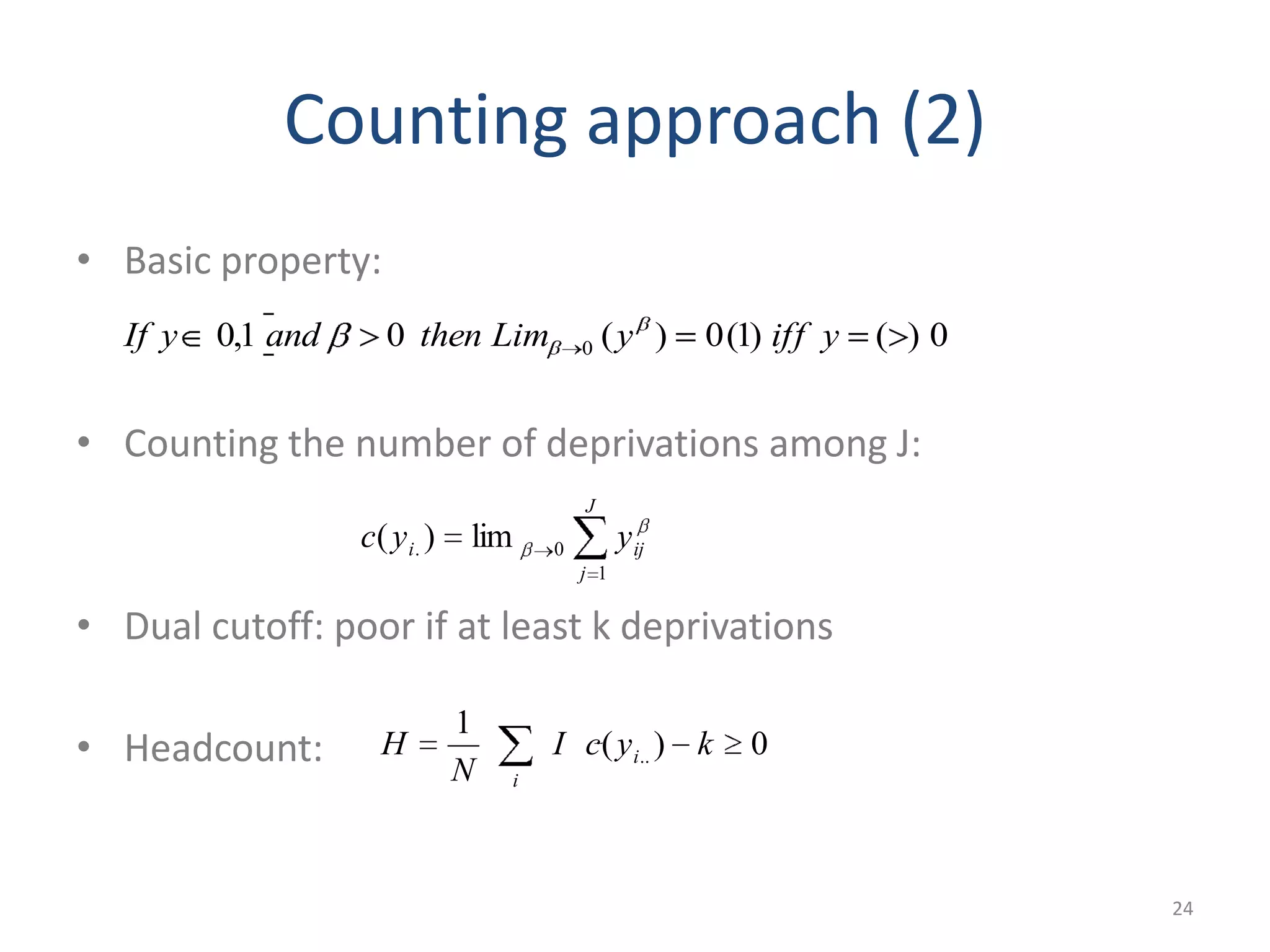

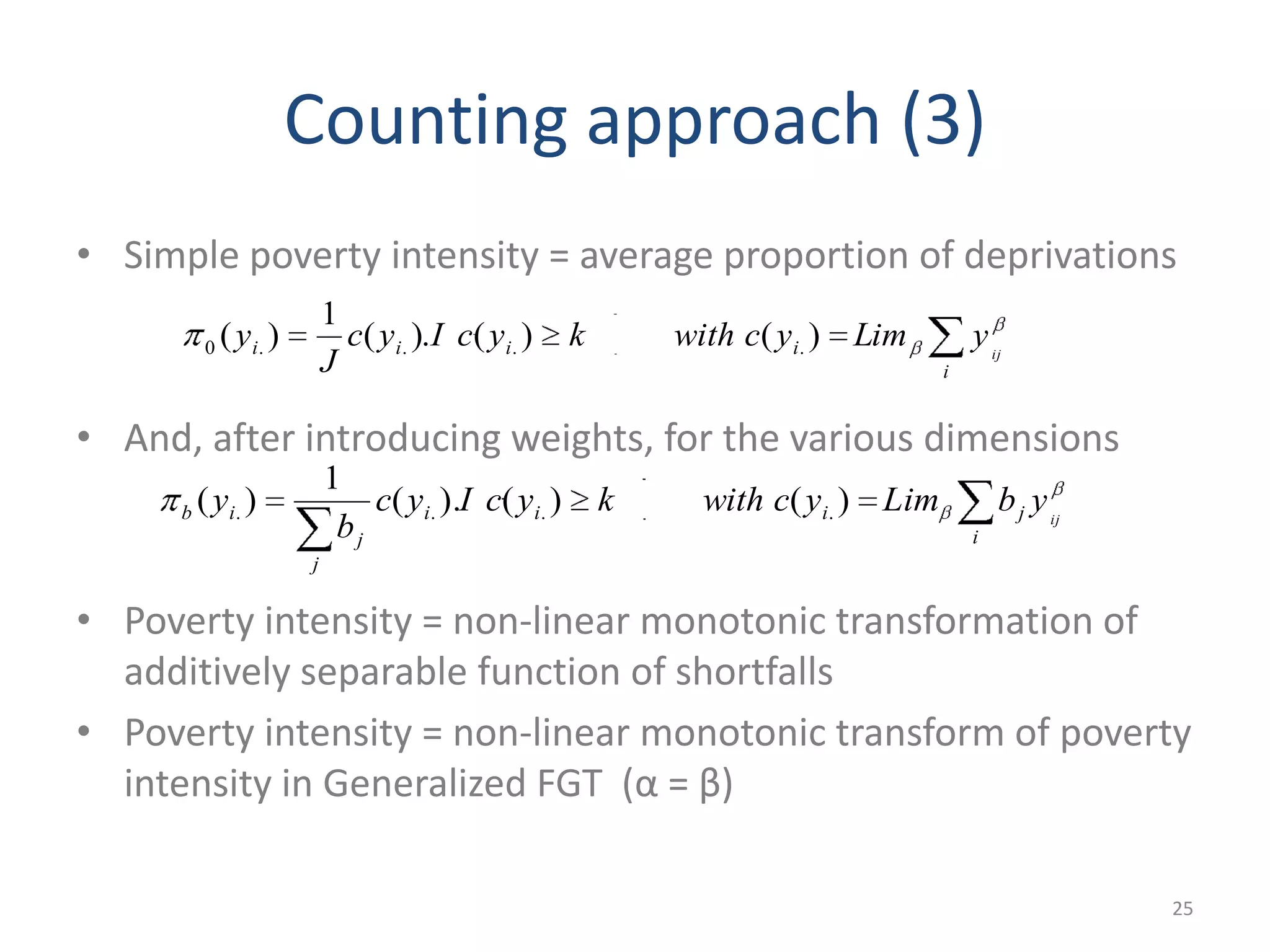

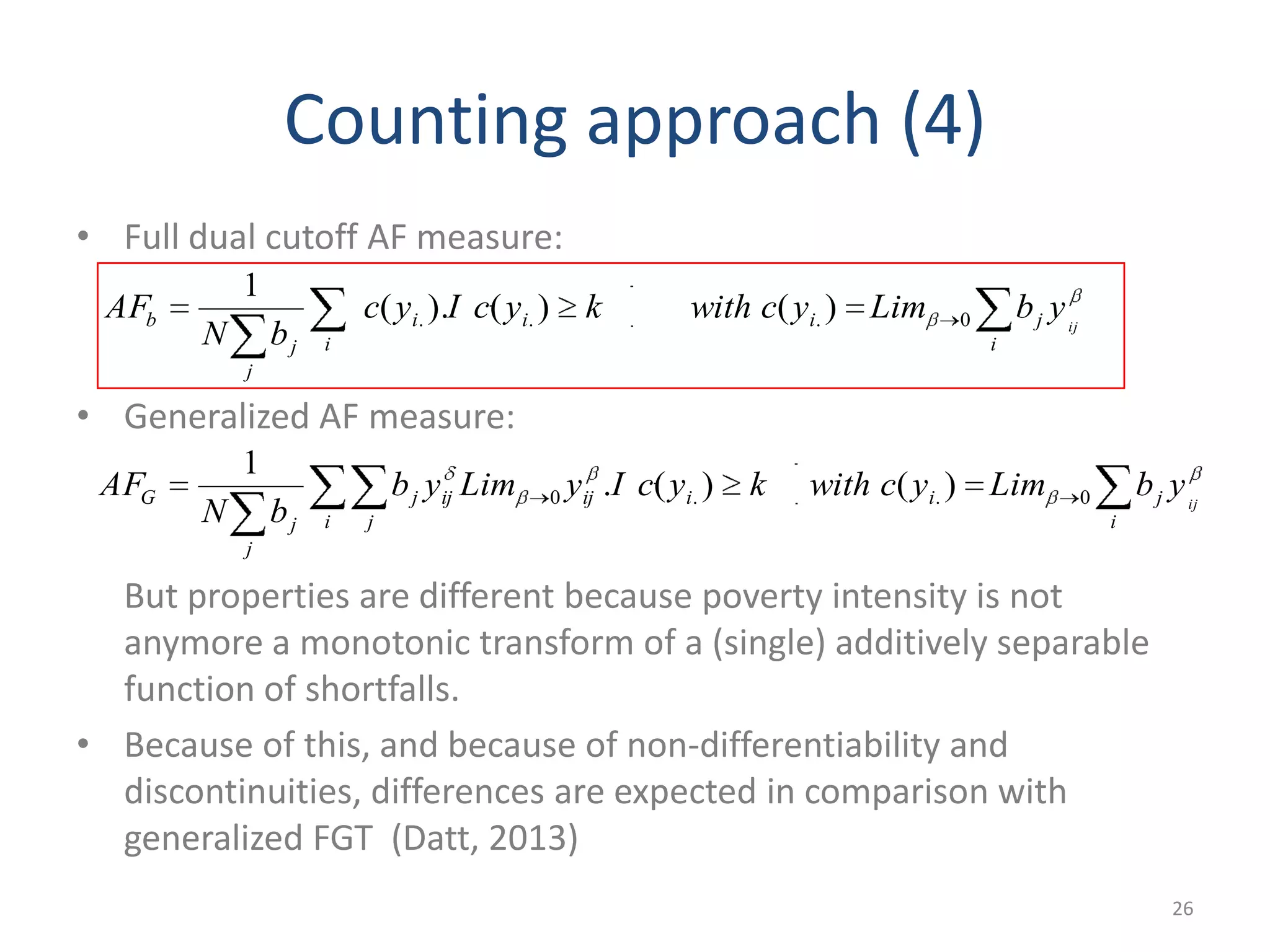

The document discusses multi-dimensional poverty measurement, highlighting the complexities and various approaches, including the capability approach, statistical methods, and the counting approach. It evaluates existing measures, questions the effectiveness of aggregating dimensions into single indicators, and emphasizes the importance of understanding different dimensions of poverty. The conclusion reflects ongoing debates and the necessity for appropriate frameworks and measures in understanding poverty.