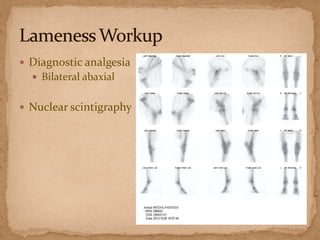

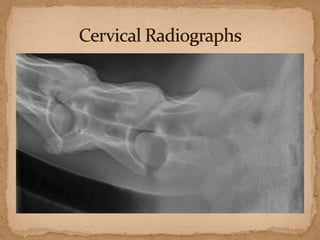

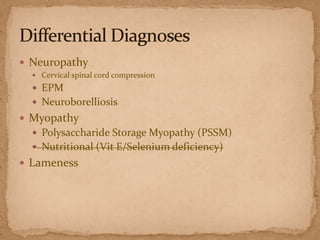

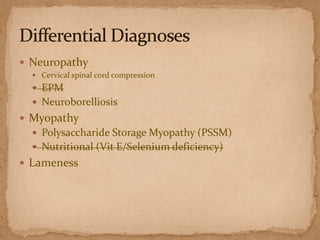

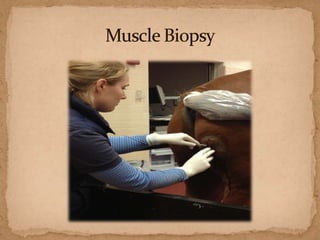

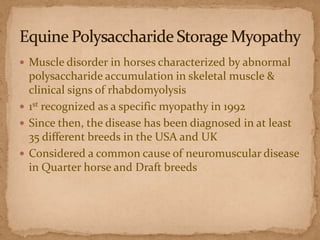

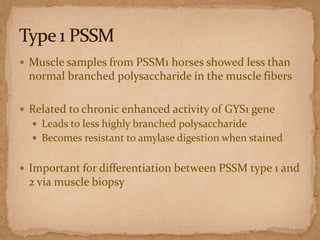

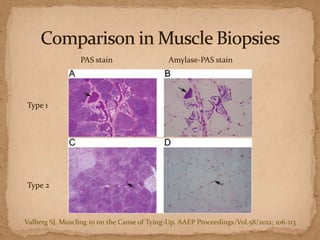

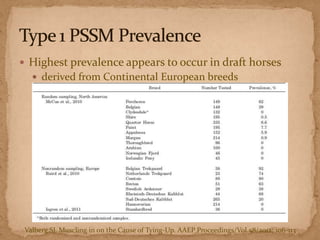

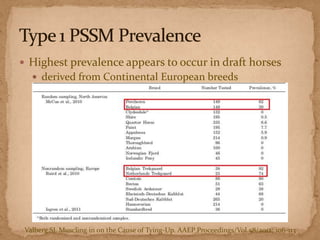

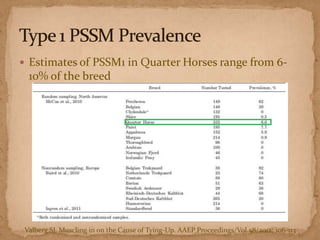

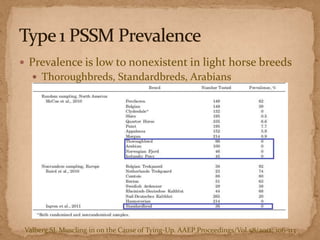

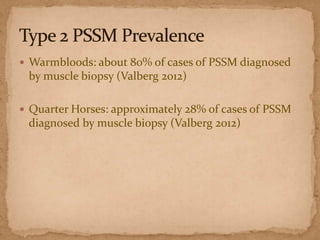

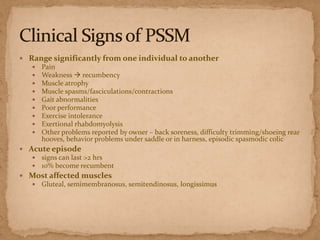

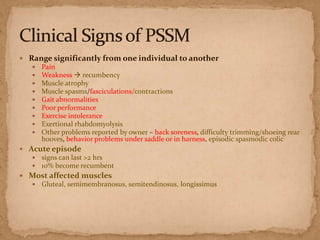

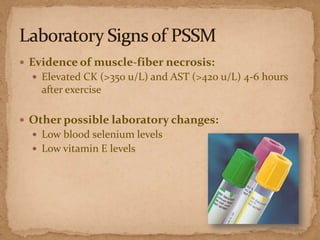

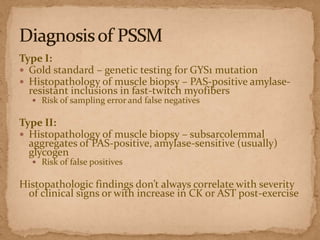

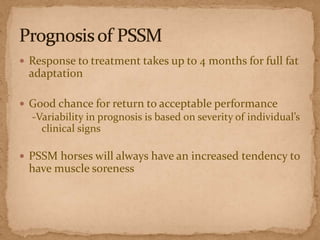

This document describes a case of a 9-year-old warmblood gelding presenting with progressive ataxia, weakness, and poor performance over 4-5 months. Physical examination revealed grade 1 ataxia and grade 2/5 lameness in the left front and right hind limbs. Differential diagnoses included neuropathy, myopathy such as polysaccharide storage myopathy (PSSM), and lameness. A muscle biopsy showed findings consistent with PSSM type 1. Treatment involves long-term dietary management to reduce glucose and insulin levels.