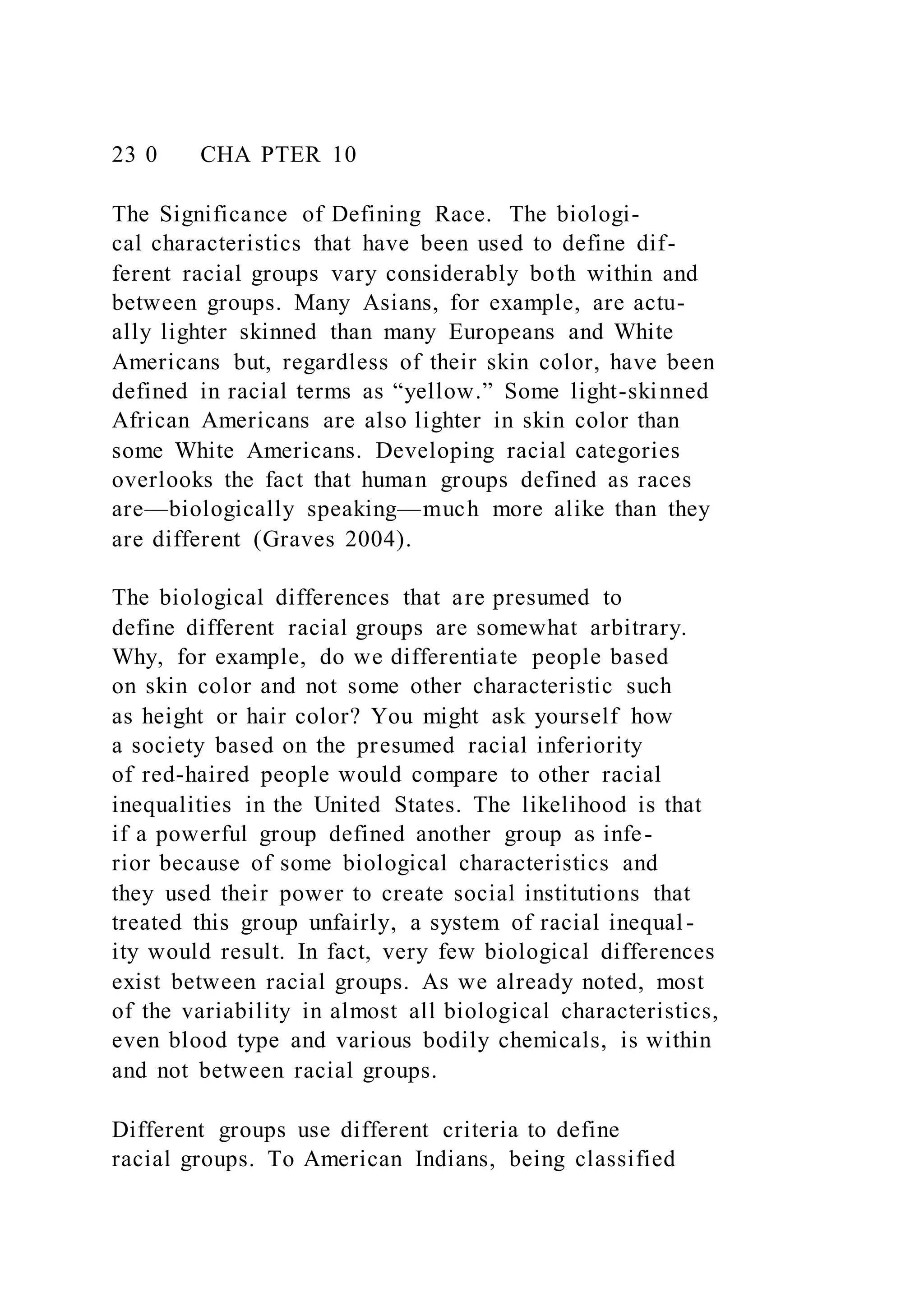

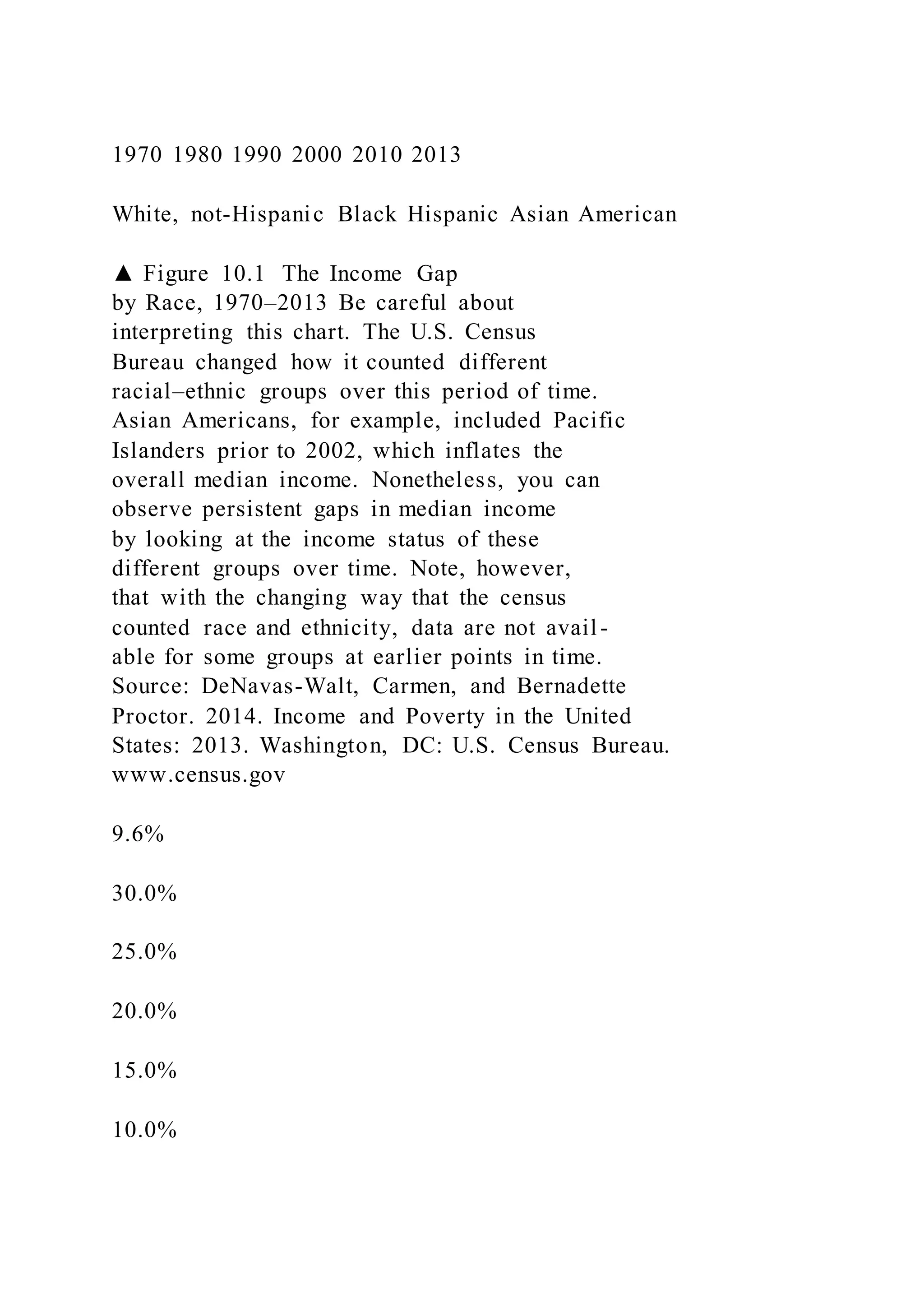

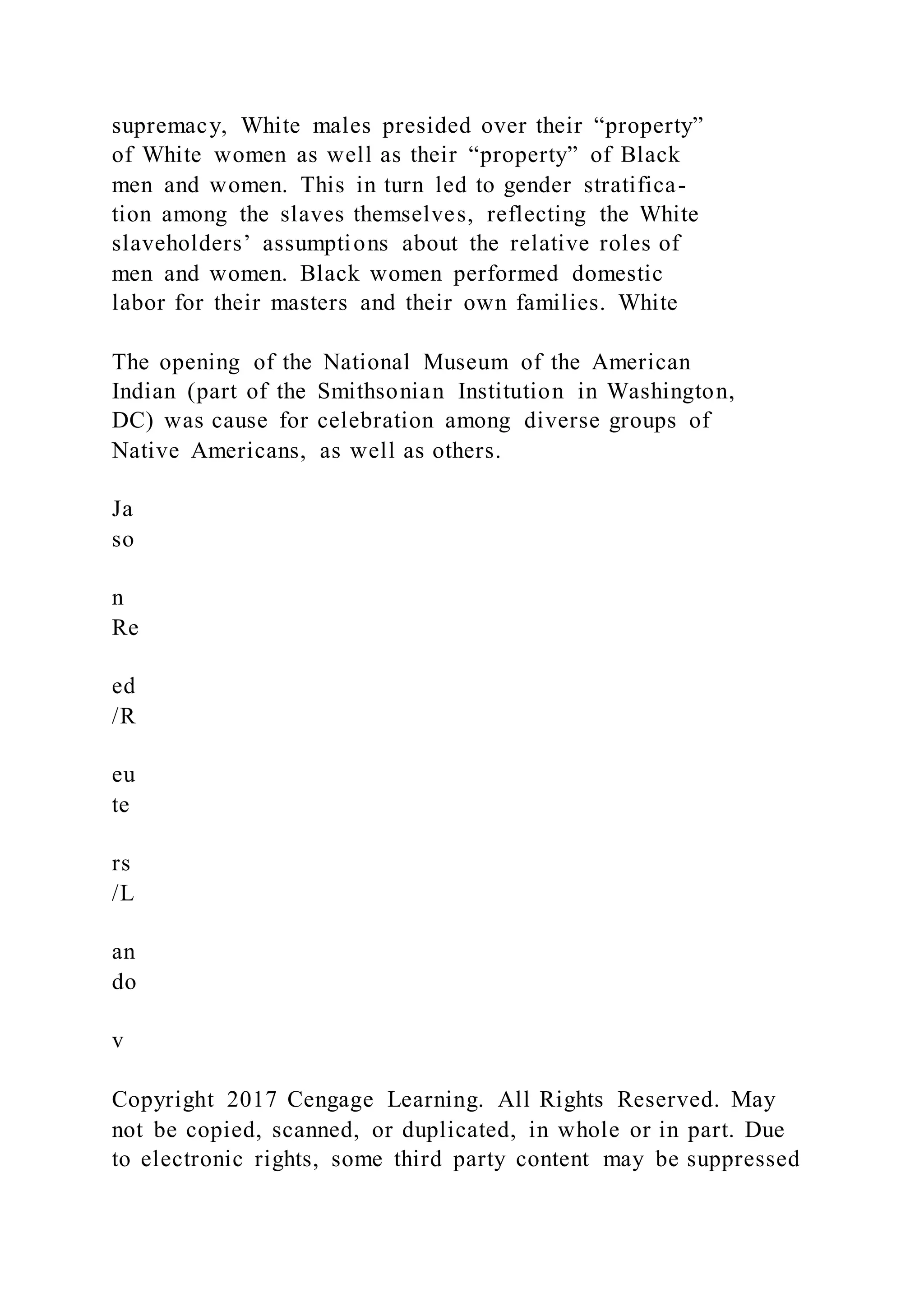

The document discusses the prevalence of racial and ethnic prejudice and racism within American society, exemplified by various violent and discriminatory incidents. It emphasizes that race and ethnicity are social constructs that play significant roles in social stratification, challenging the notion of a 'postracial' society. Through exploring the complexities of racial and ethnic identities, it illustrates how these constructs have historically influenced social interactions and institutional practices.

![is

io

n

[L

C-

DI

G-

pp

pr

s-

00

36

8]

Copyright 2017 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May

not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due

to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed

from the eBook and/or eChapter(s).

Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does

not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage

Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any

time if subsequent rights restrictions require it.

RACE AND E THN IC ITY 24 5

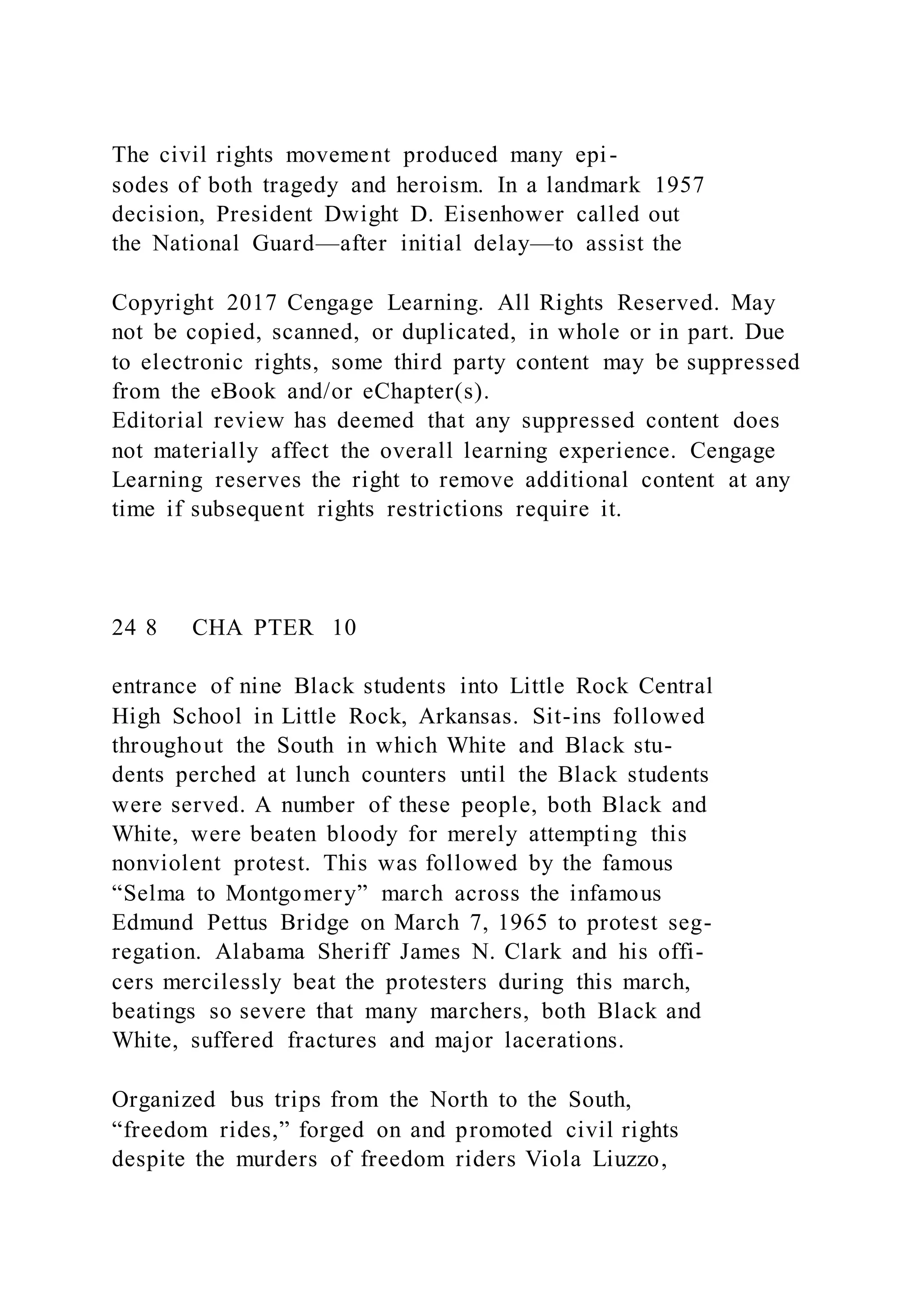

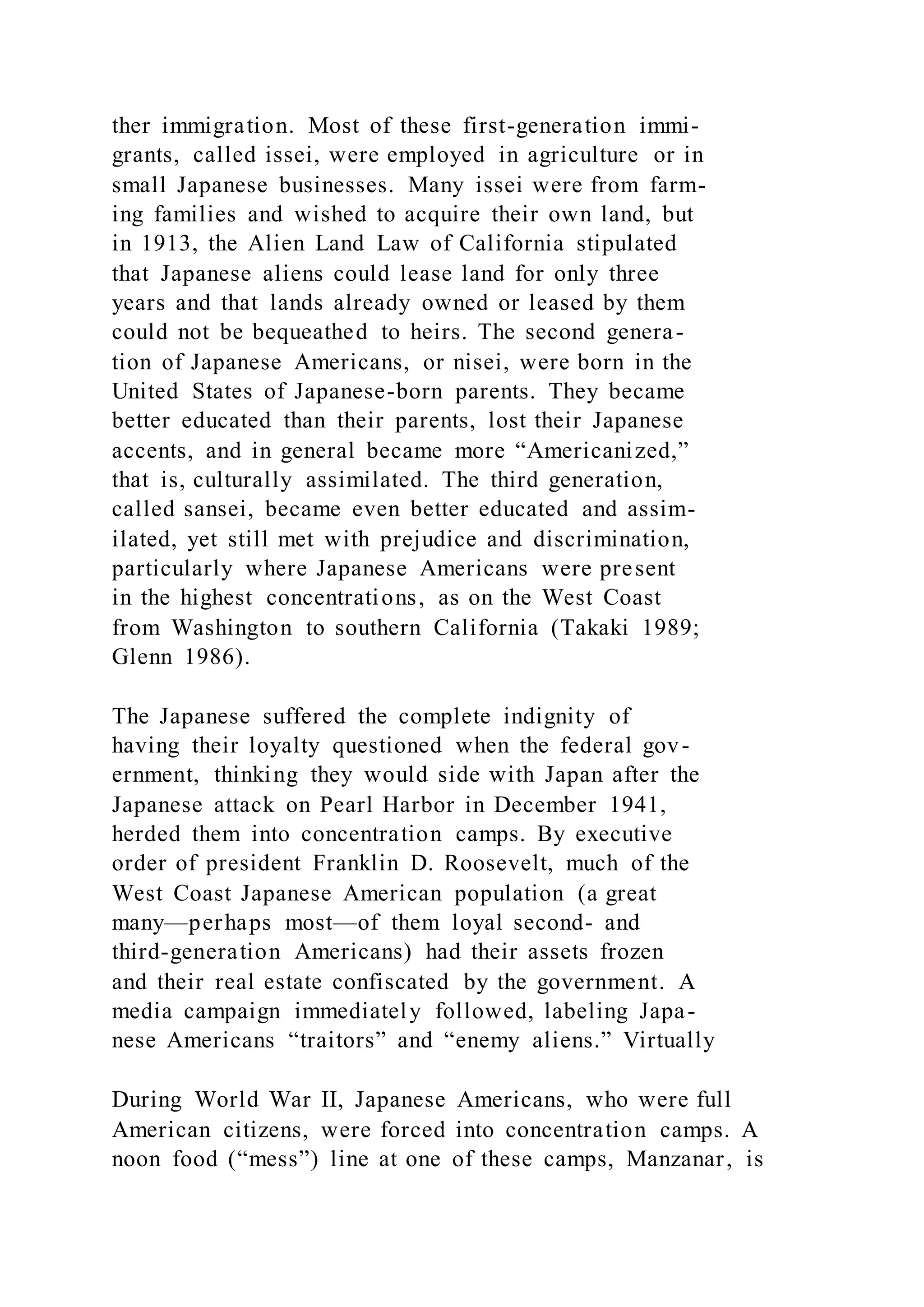

all Japanese Americans in the United States had been

removed from their homes by August 1942, and some

were forced to stay in relocation camps until as late as](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/michaelb-220922224907-ac9e15dd/75/Michael-B-ThomasGetty-Im-69-2048.jpg)