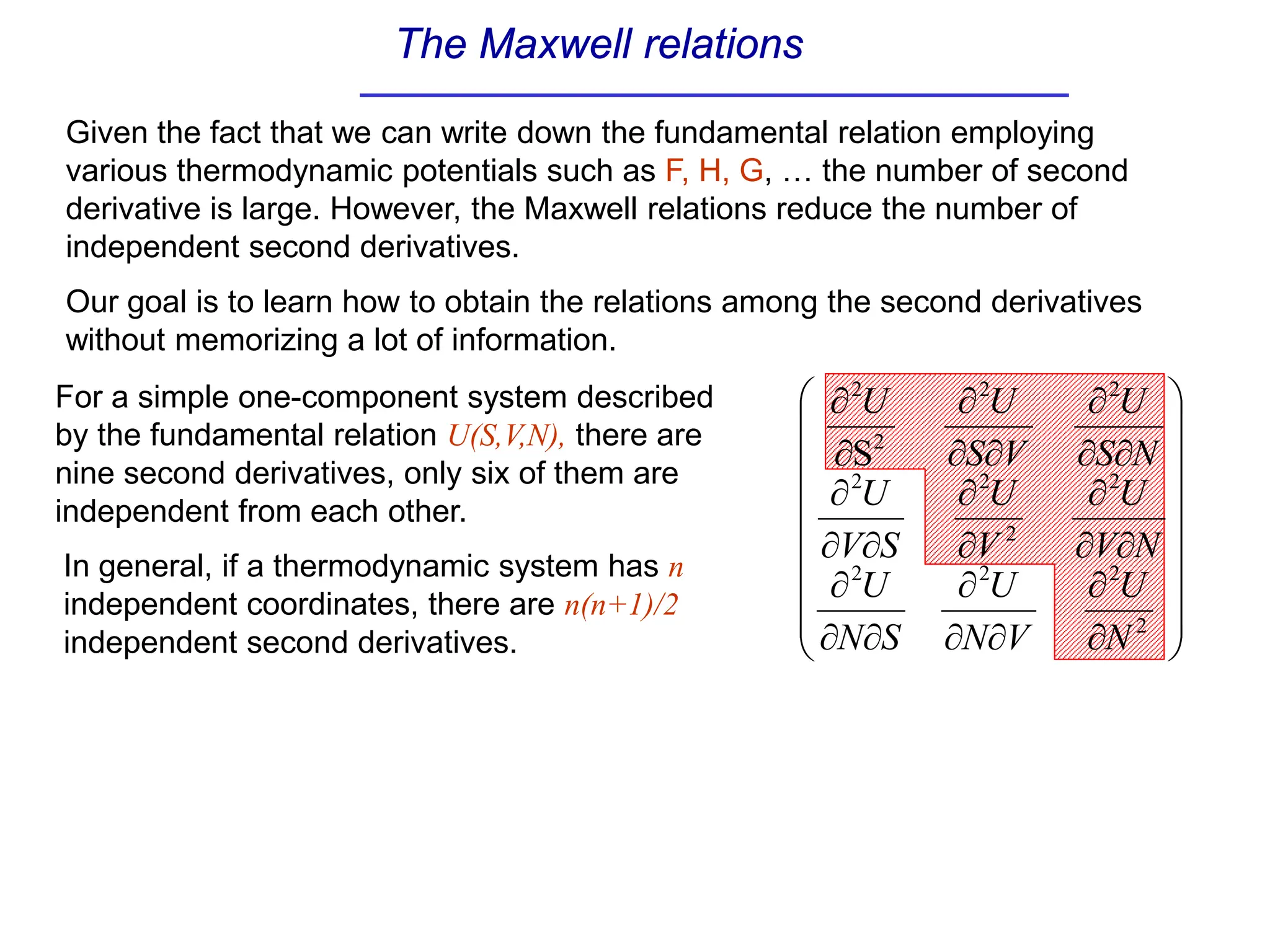

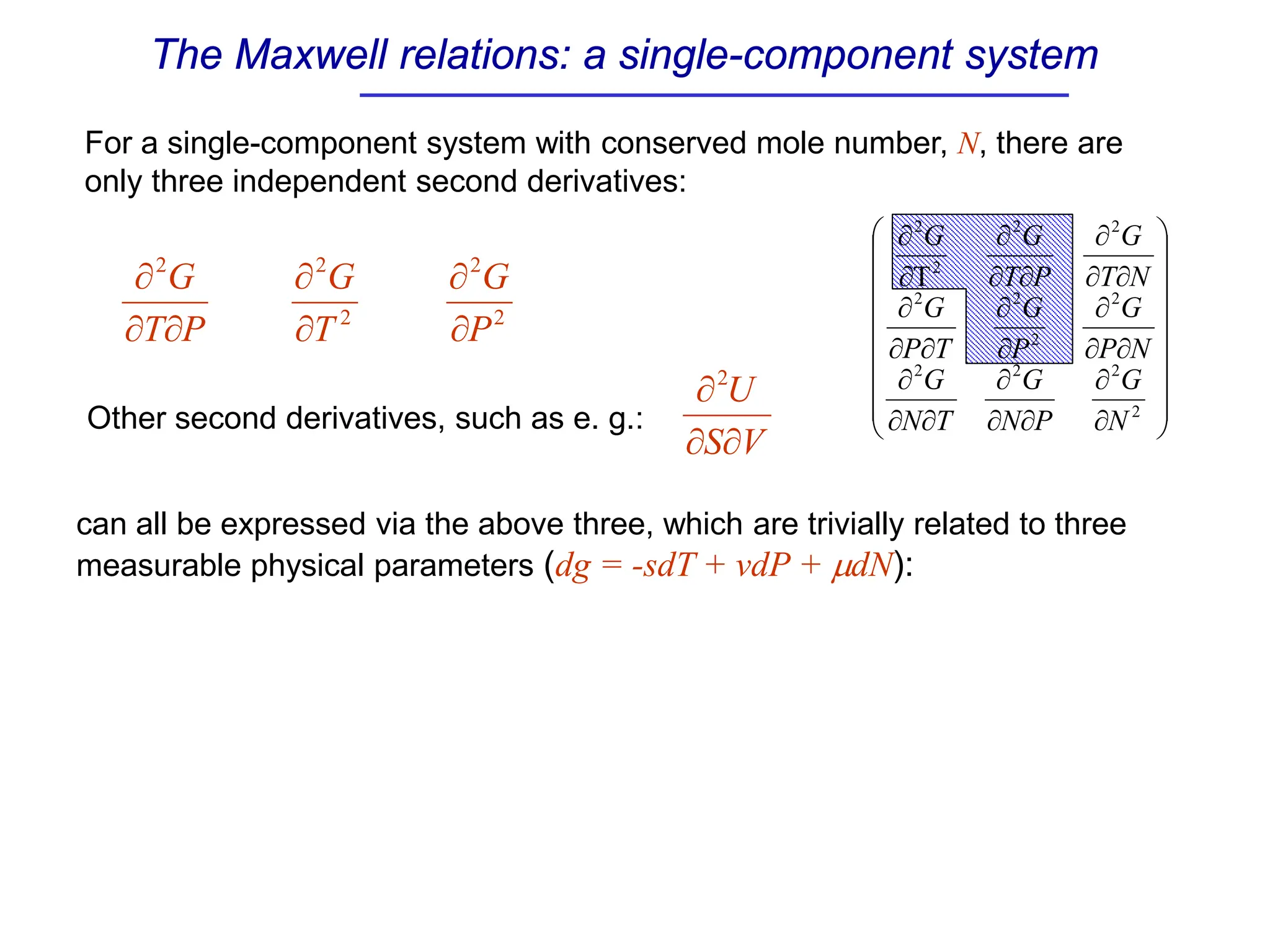

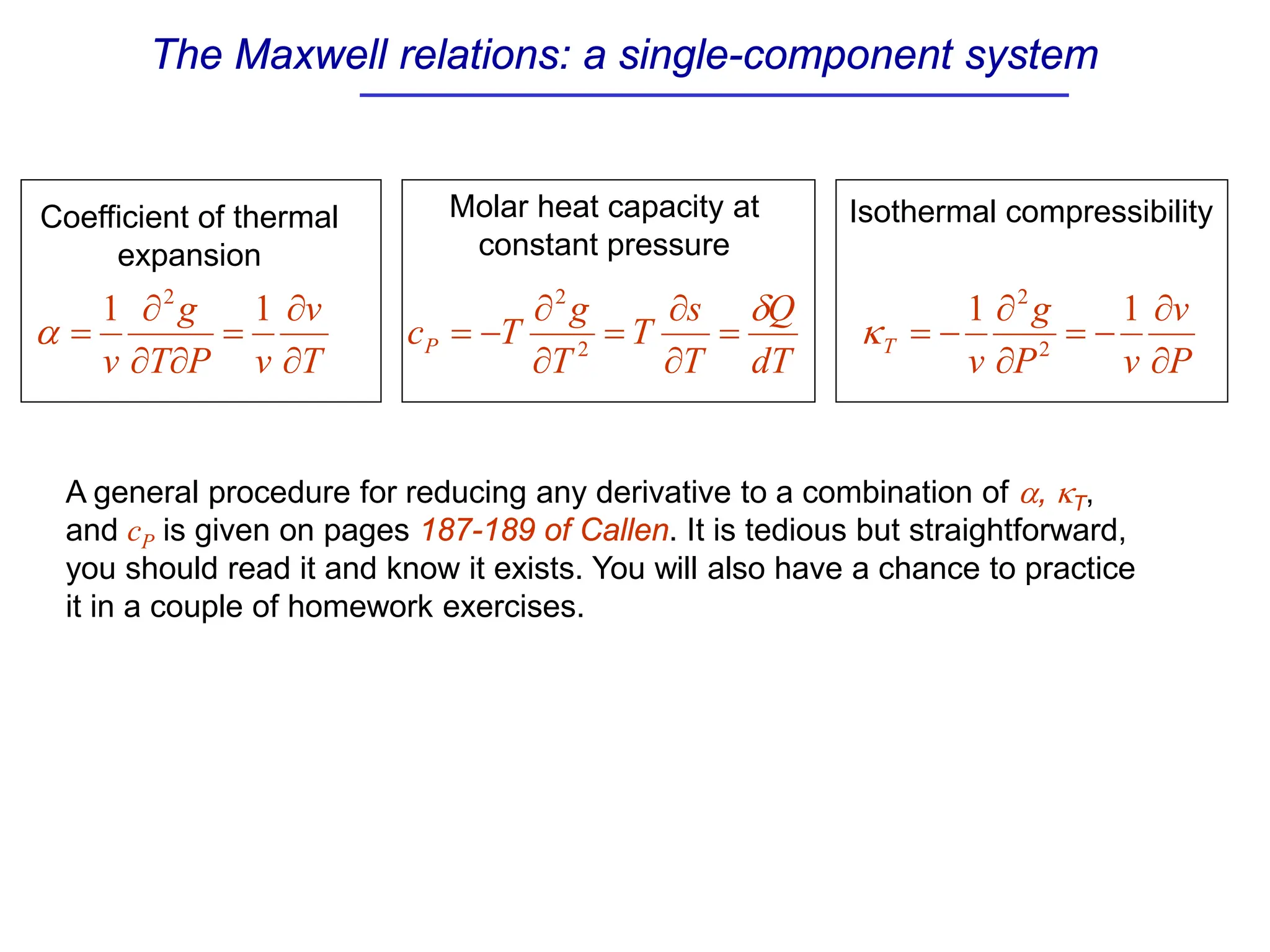

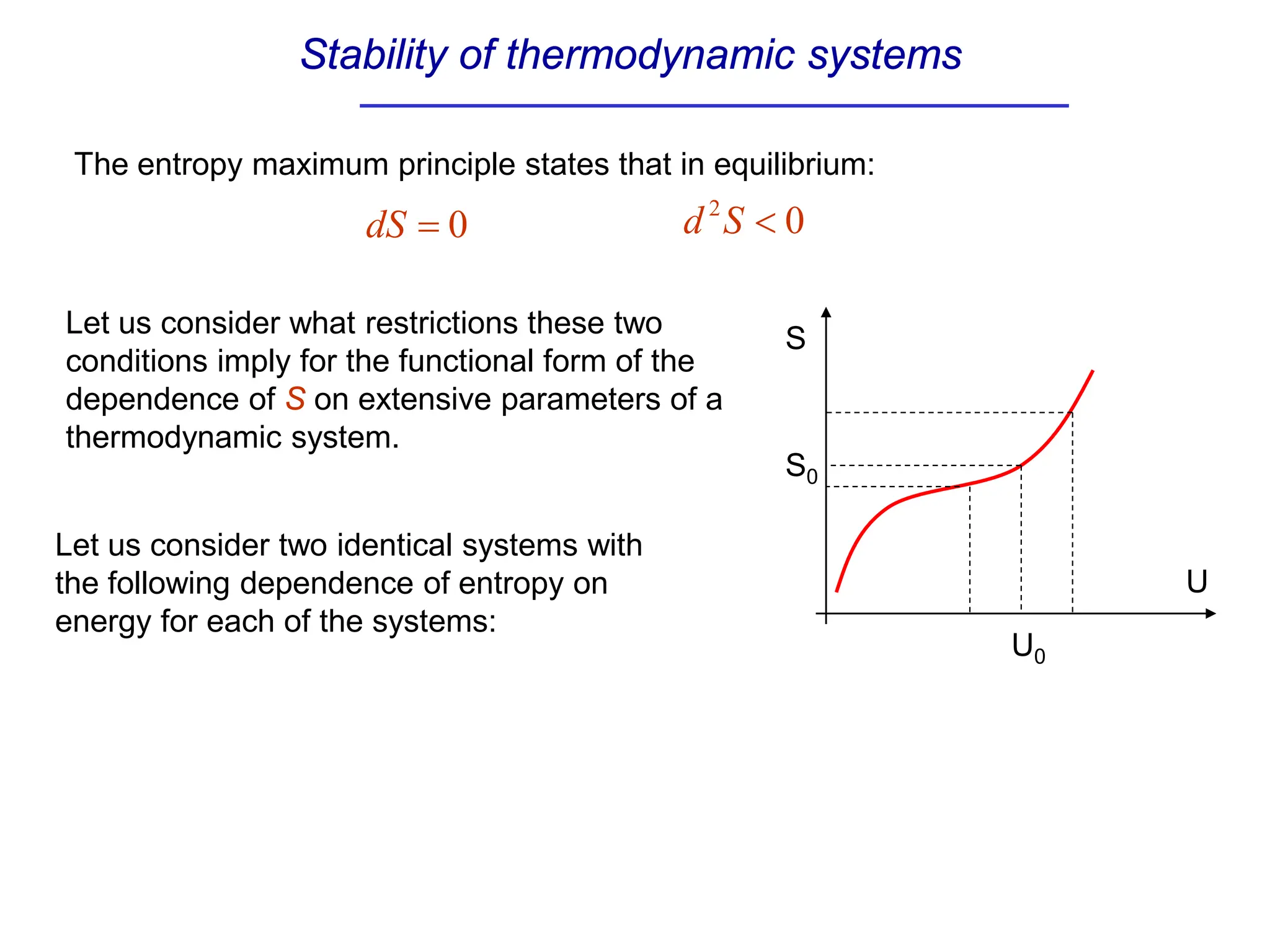

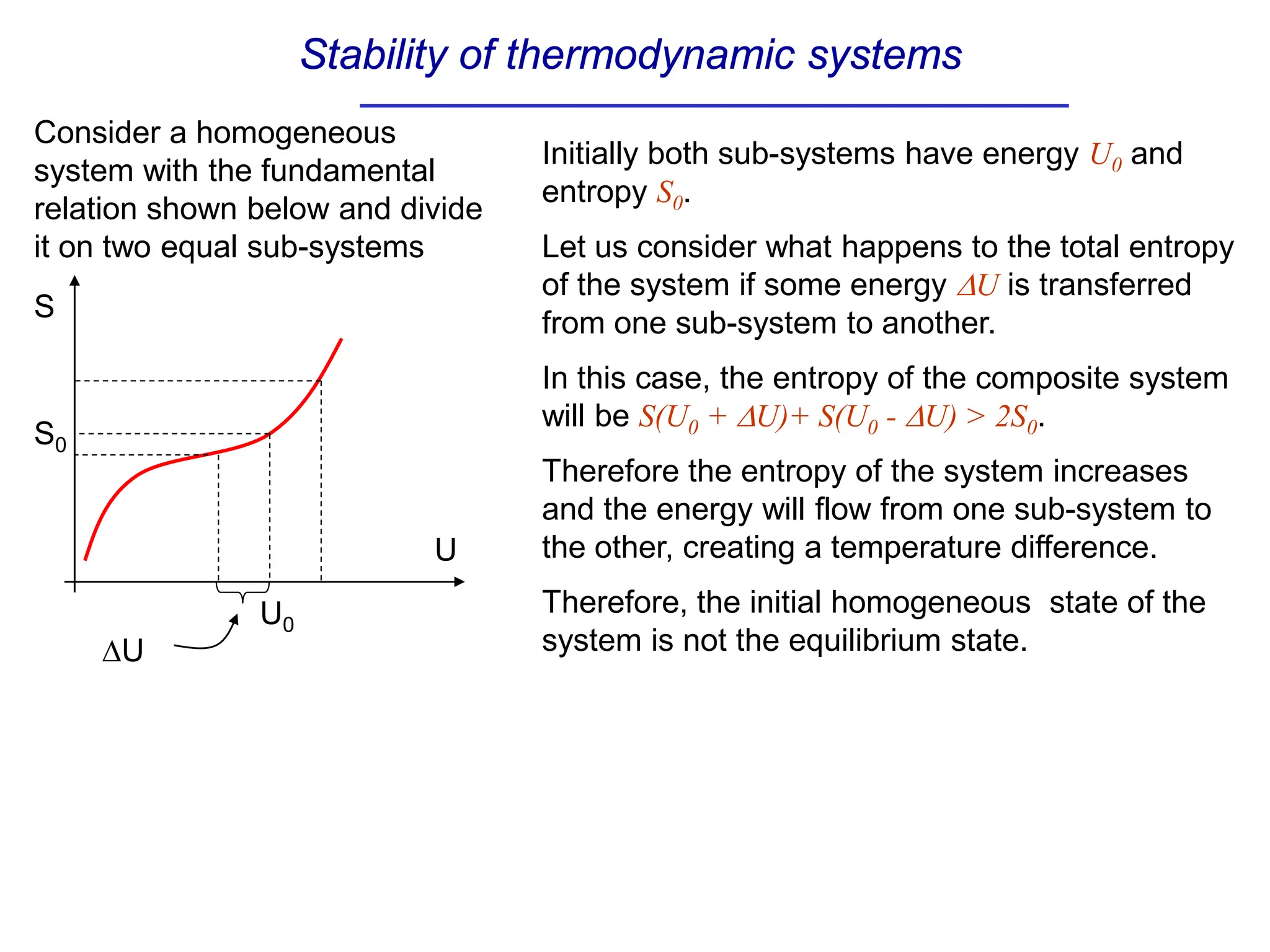

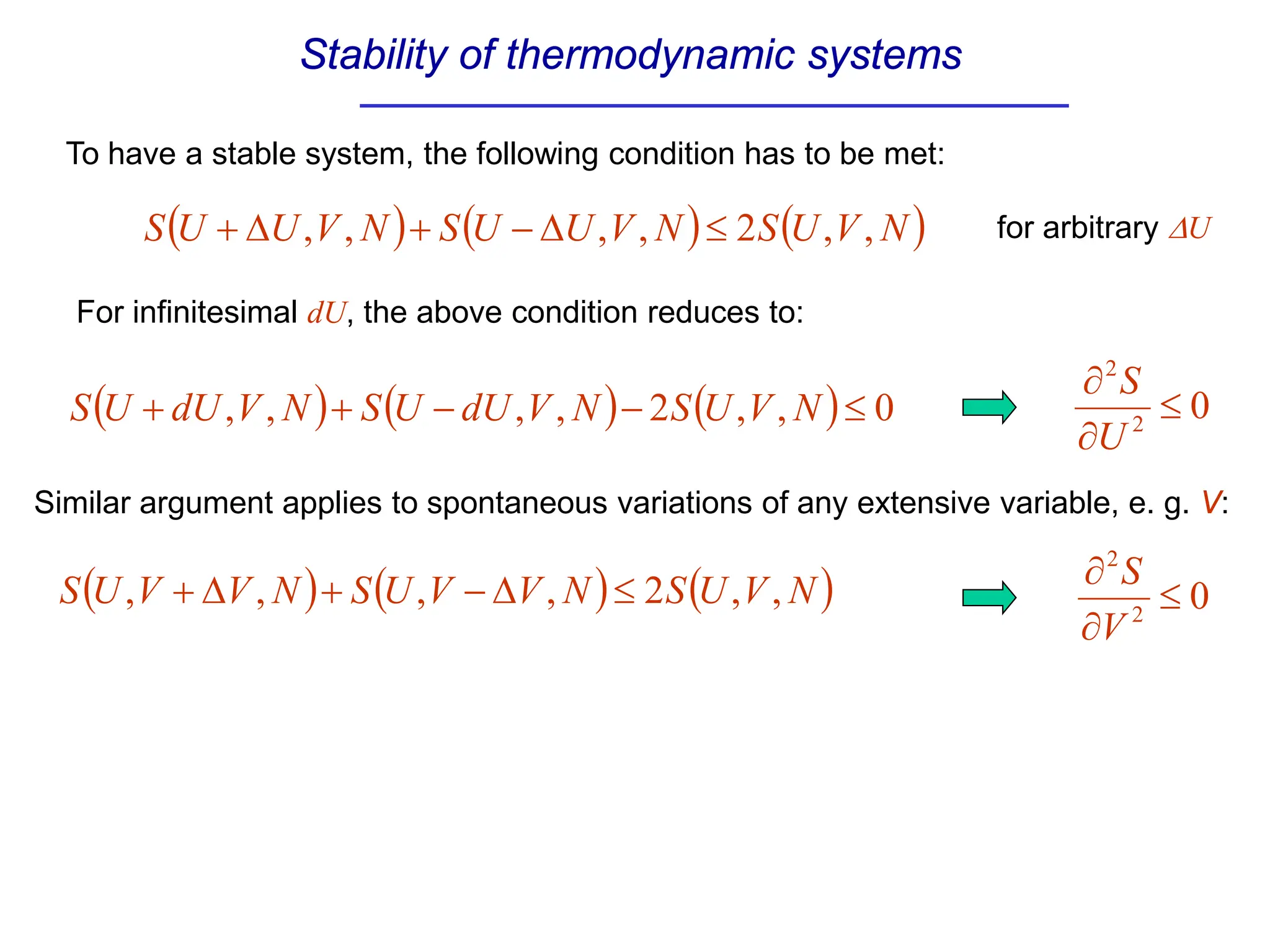

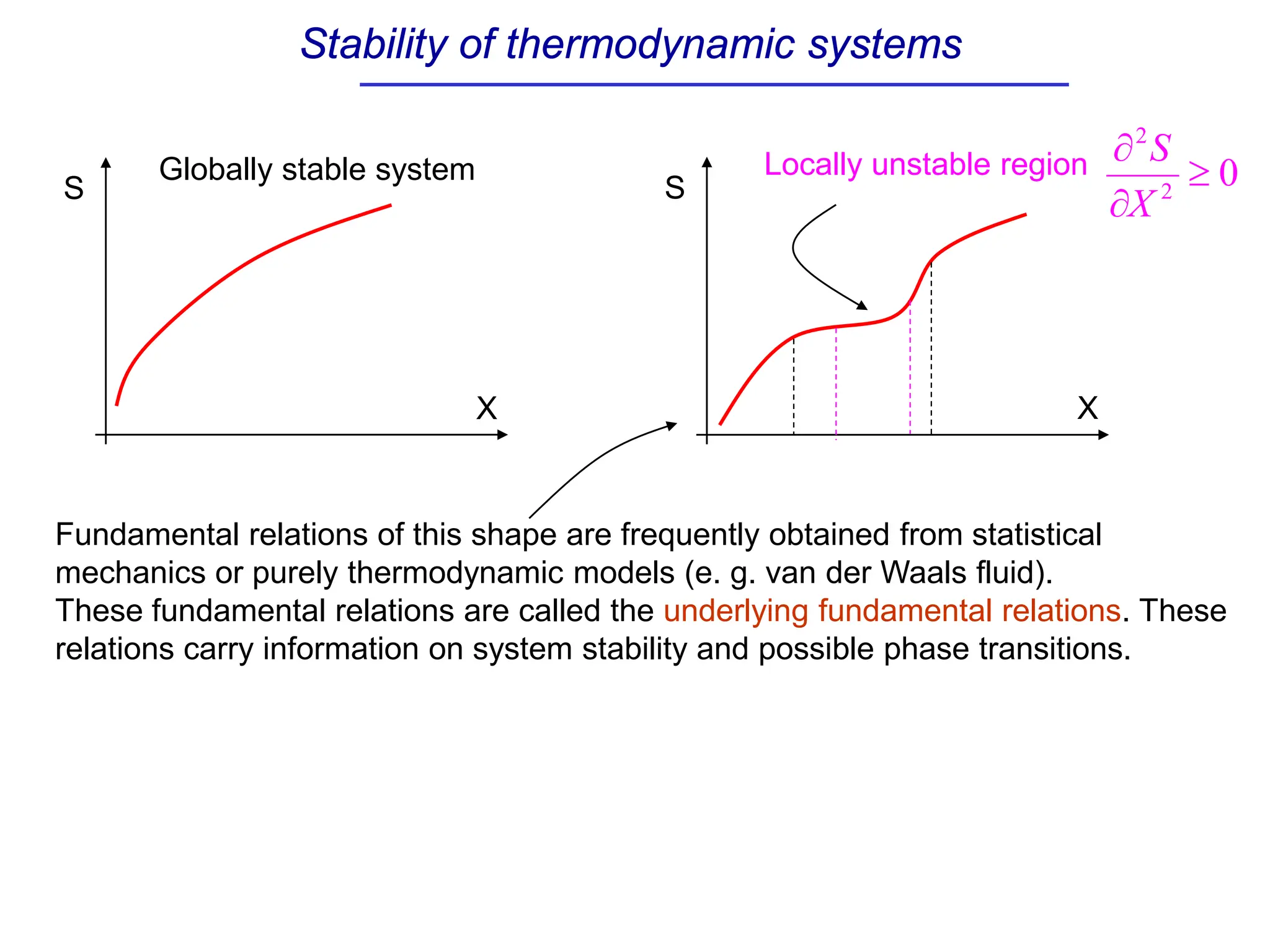

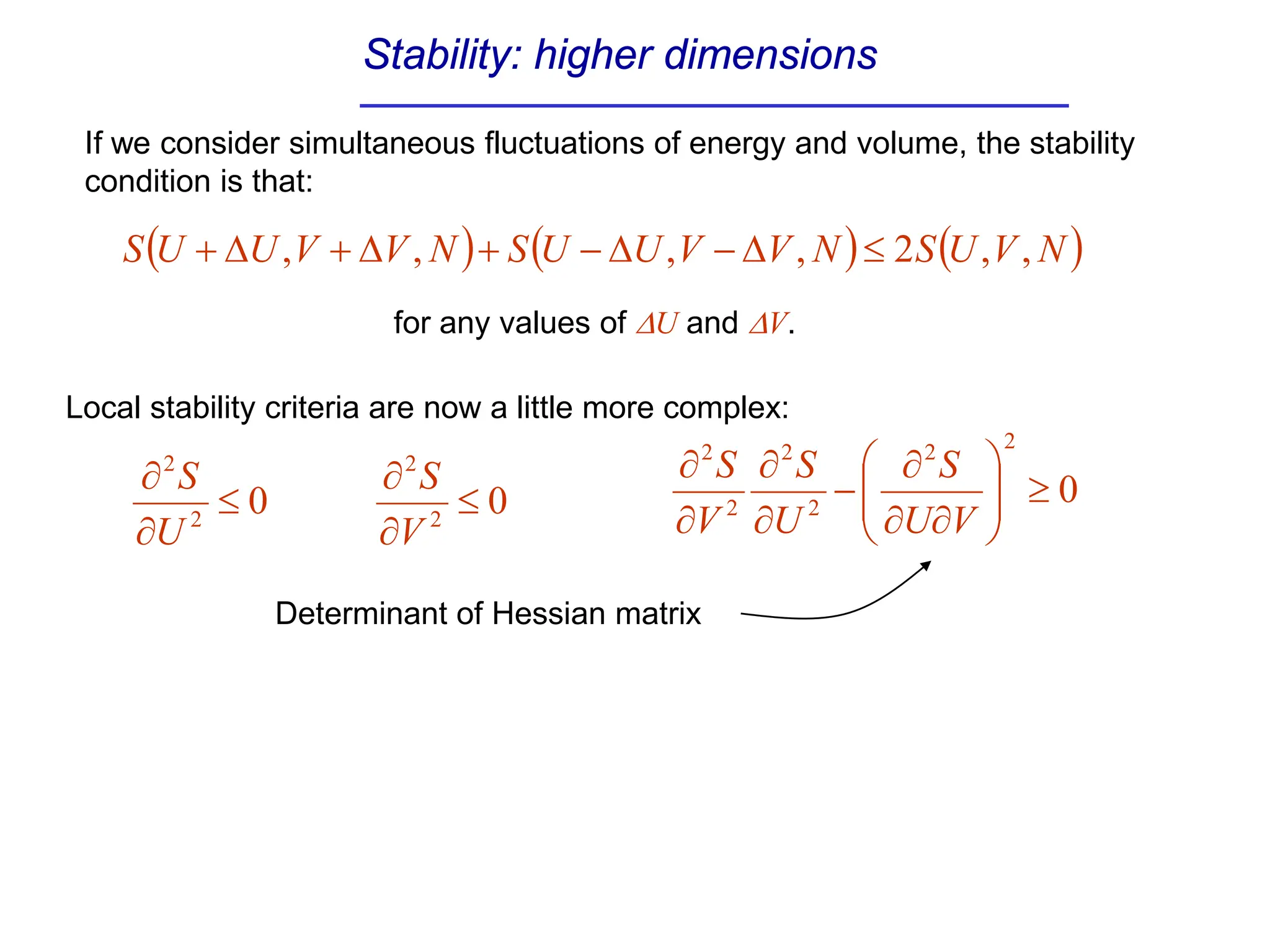

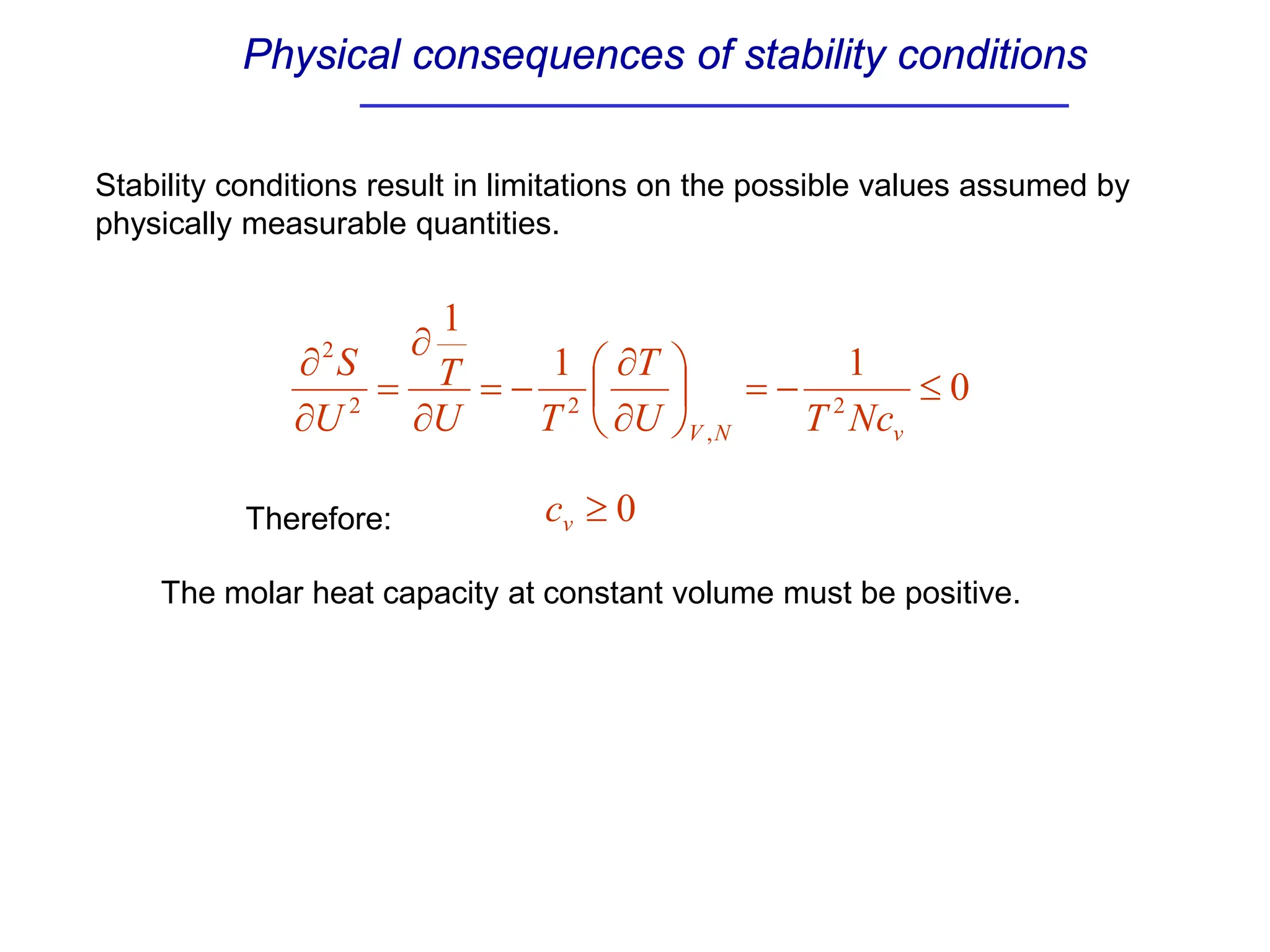

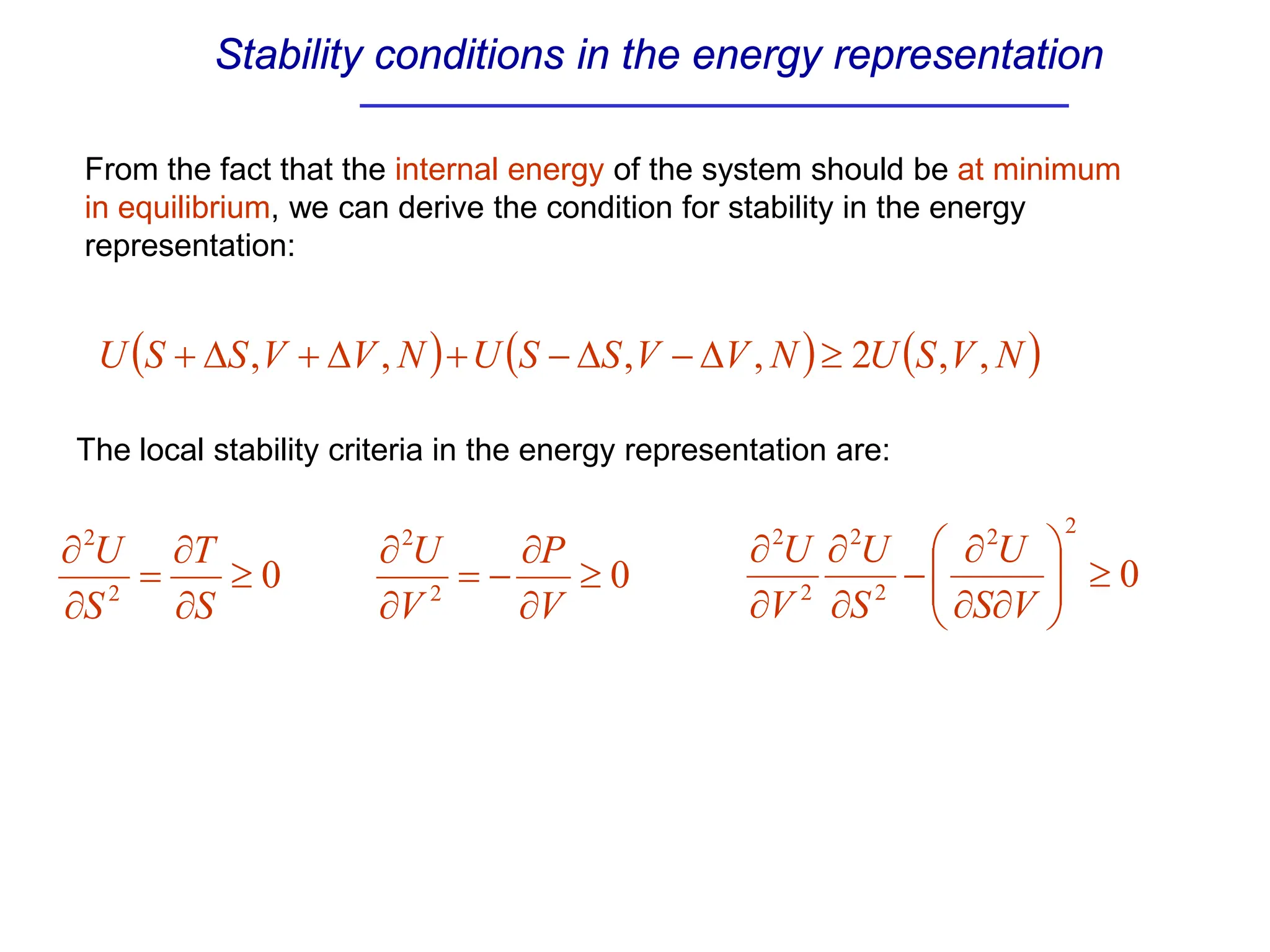

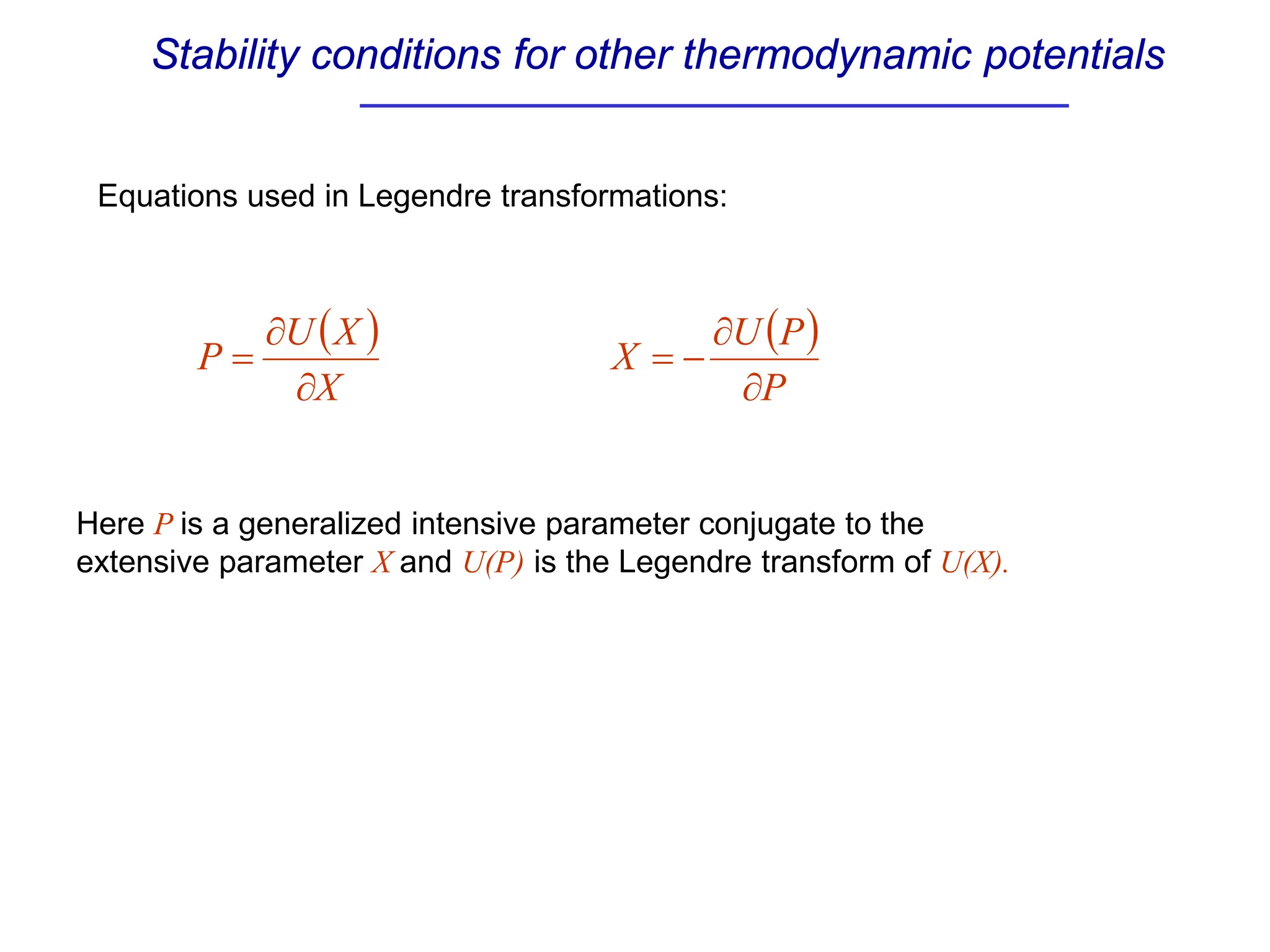

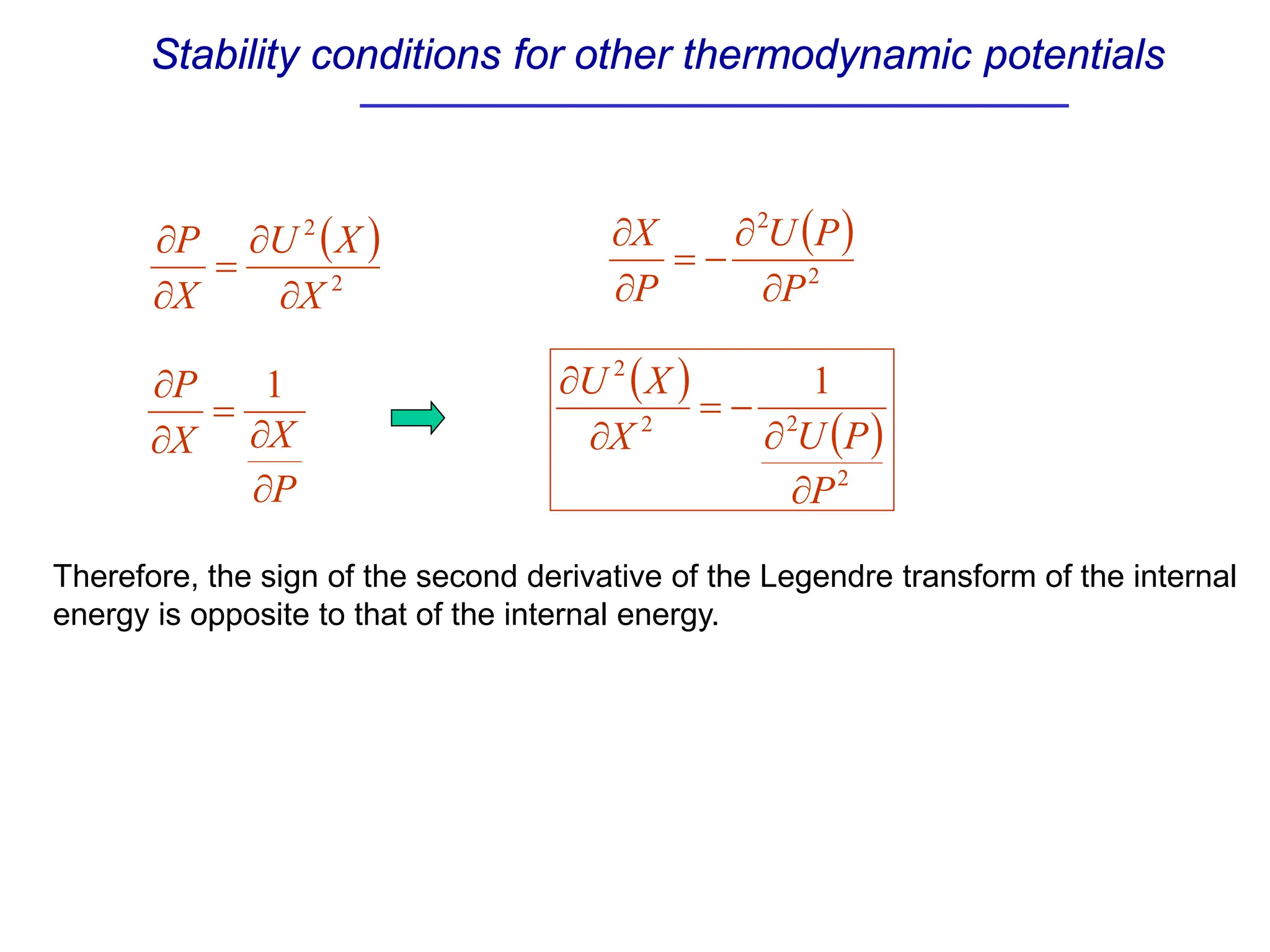

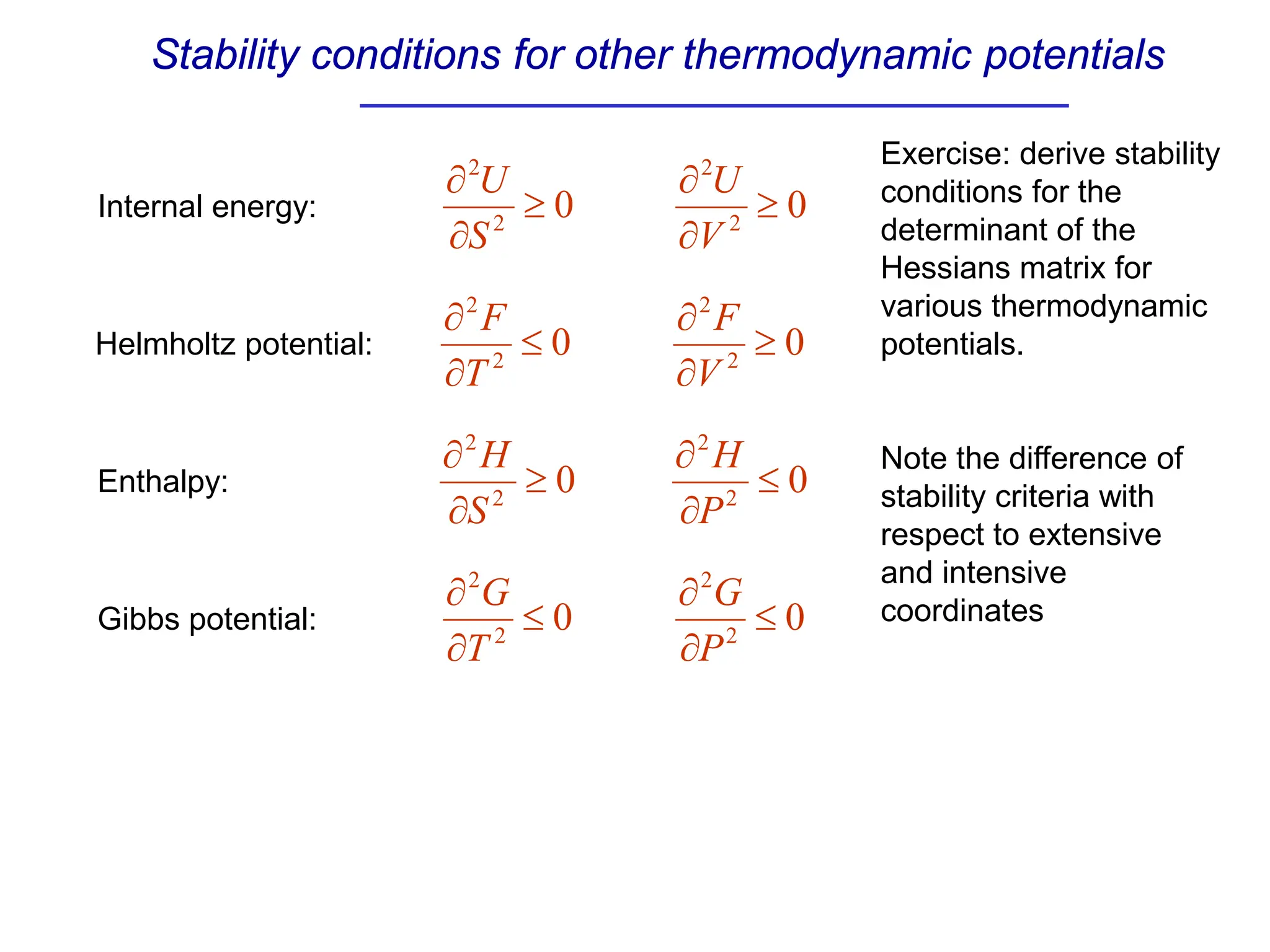

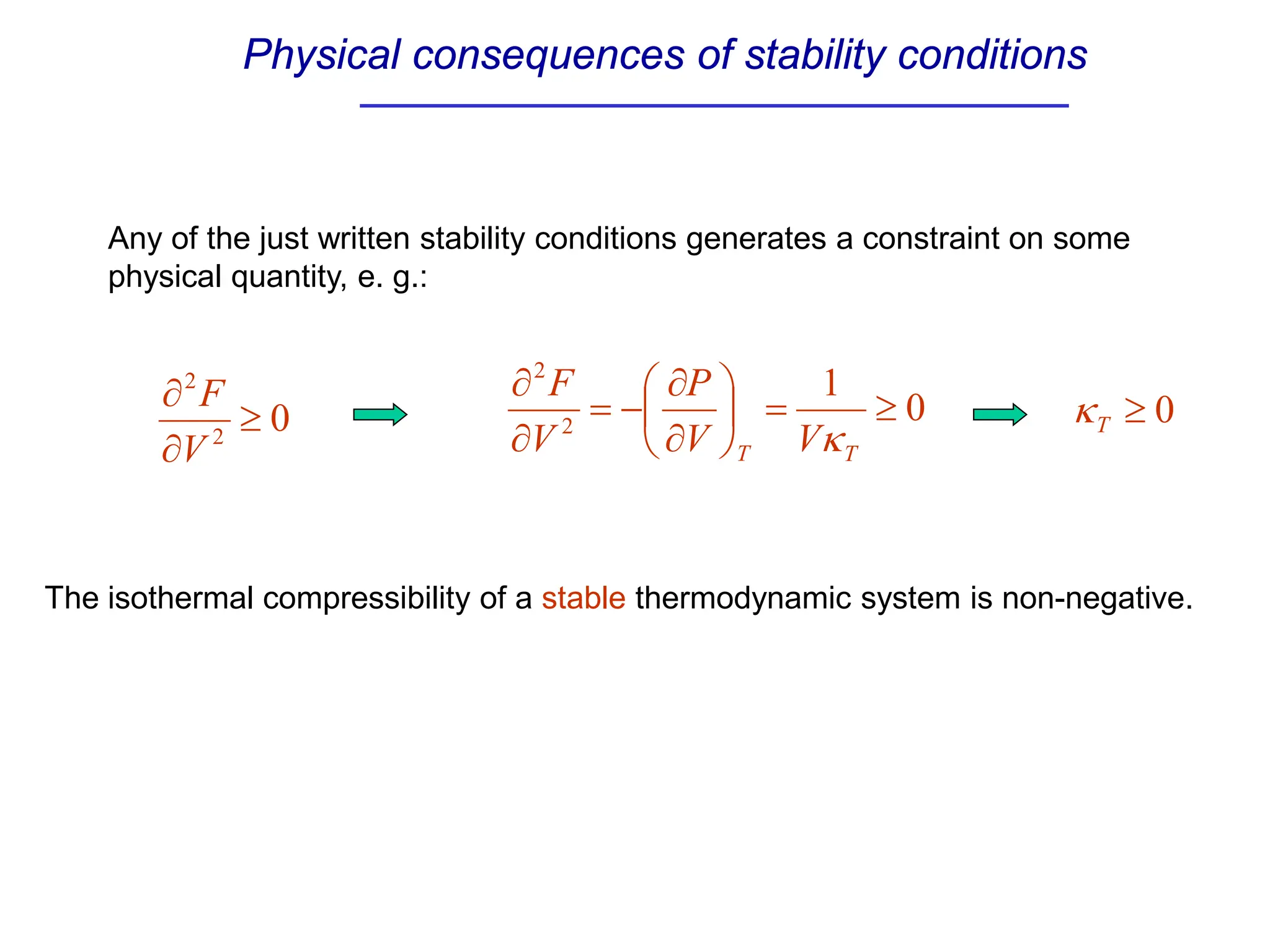

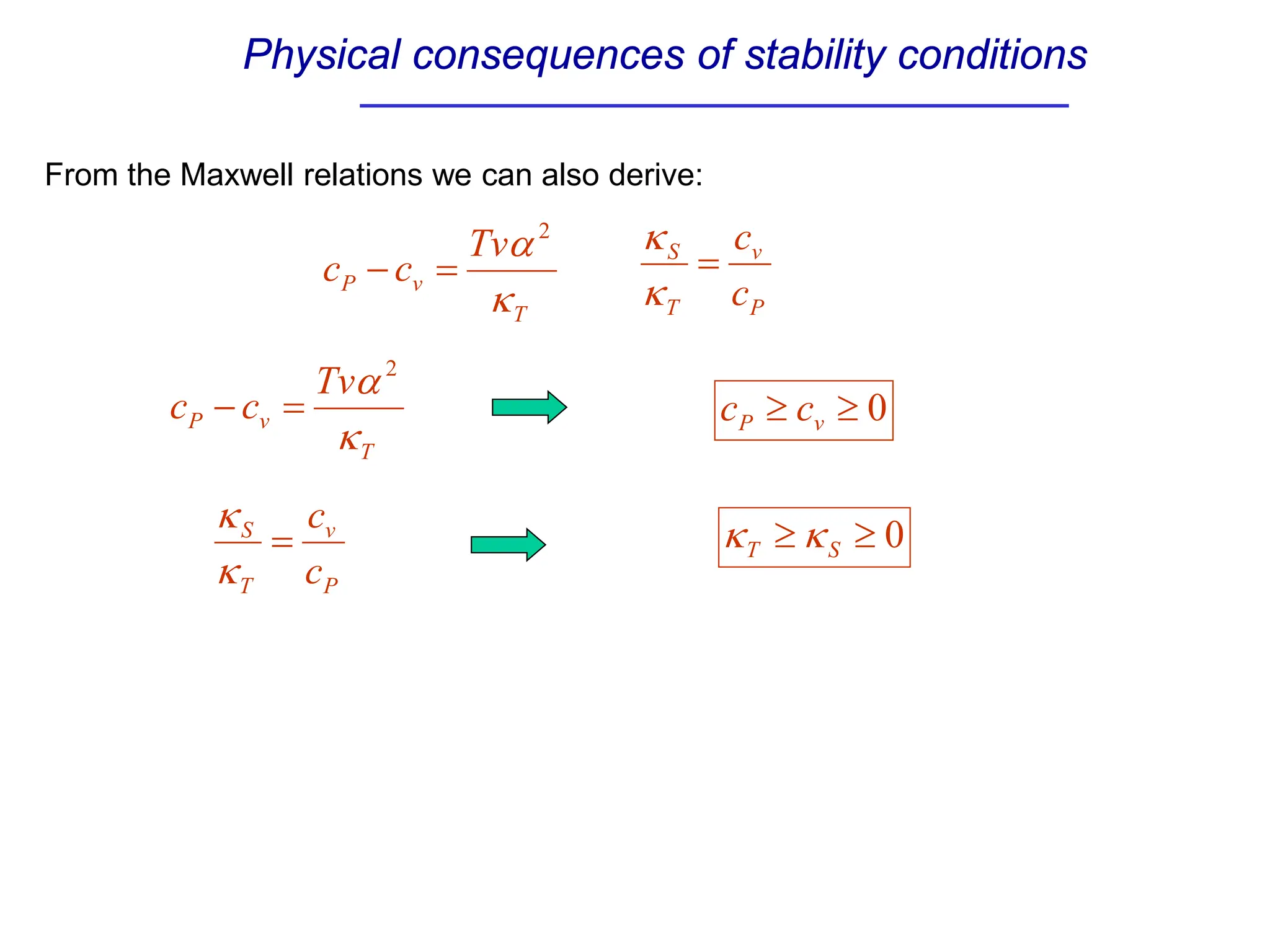

The document discusses stability conditions for thermodynamic systems. It explains that for a system to be in stable equilibrium, its entropy must be maximized for small variations in extensive parameters like internal energy and volume. This leads to requirements like the heat capacity being positive. Legendre transformations show that stability criteria are opposite for thermodynamic potentials versus their extensive variables. Various physical properties are also linked through inequalities imposed by stability, like compressibility being non-negative.