Big Data Management and NoSQL Databases document discusses key concepts of NoSQL databases including:

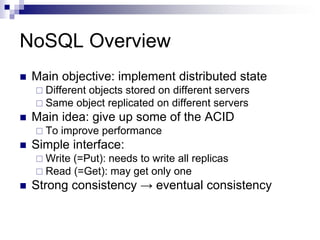

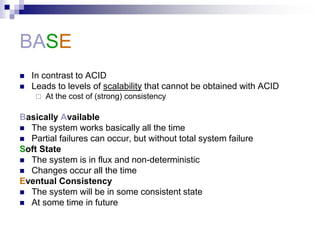

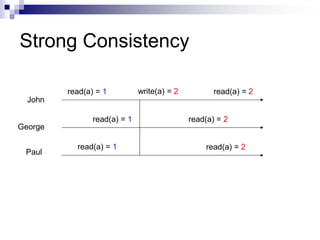

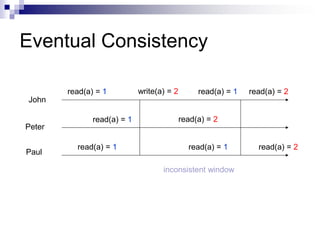

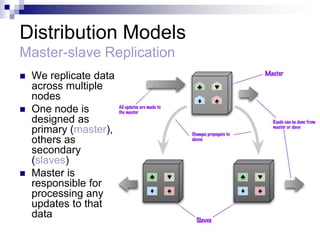

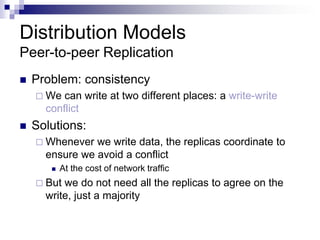

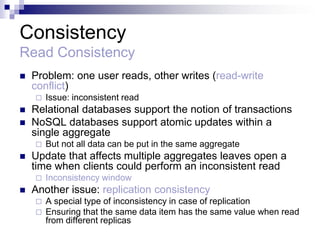

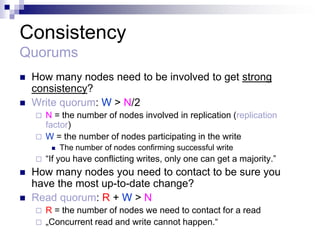

1) NoSQL databases sacrifice some ACID properties like consistency to improve performance and scalability. They use eventual consistency where after updates, all replicas may not immediately reflect the same data.

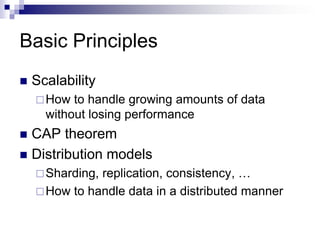

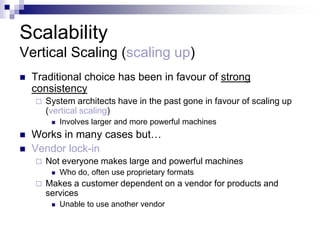

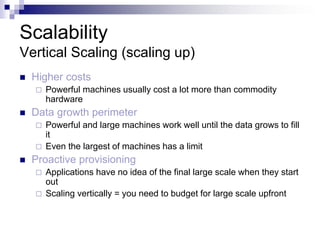

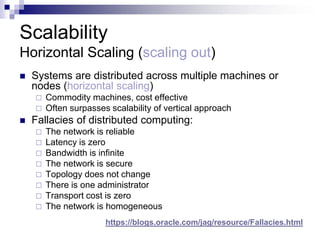

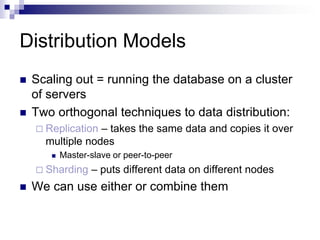

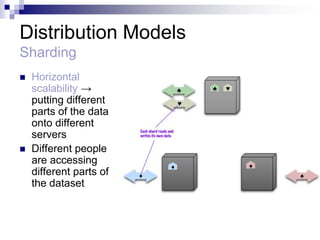

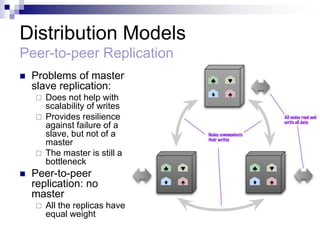

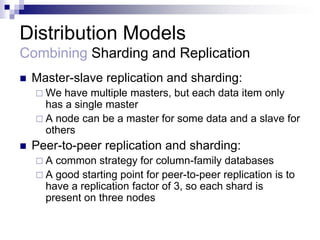

2) Horizontal scaling (scaling out) using distributed systems across multiple commodity servers is more scalable than vertical scaling (scaling up) using more powerful single servers.

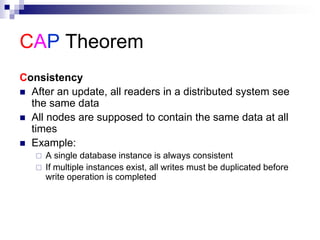

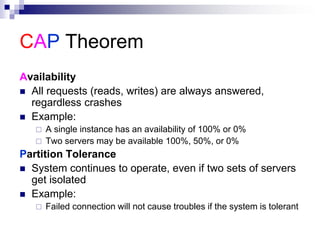

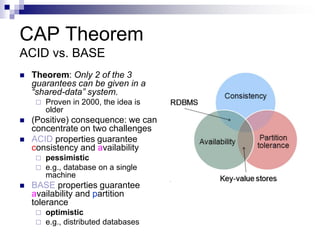

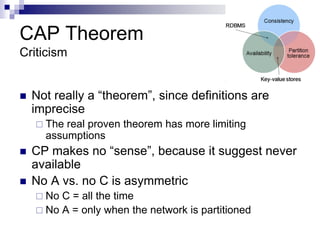

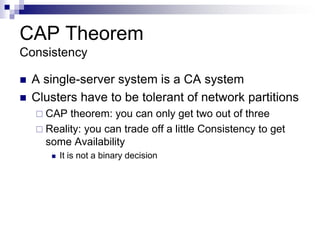

3) The CAP theorem states that a distributed system cannot achieve consistency, availability, and partition tolerance simultaneously. NoSQL databases typically choose availability and partition tolerance over strong consistency.