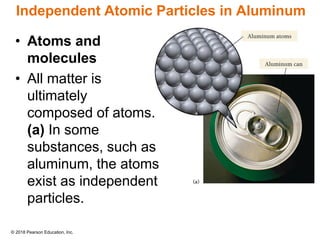

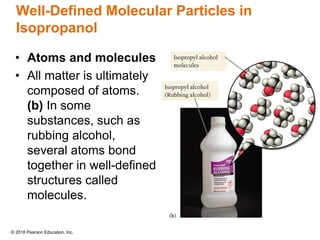

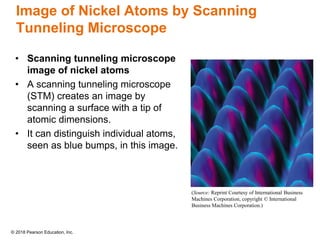

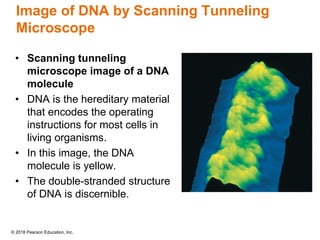

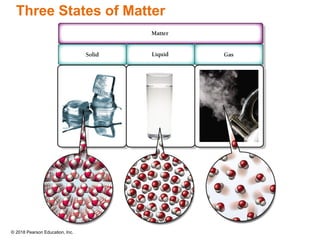

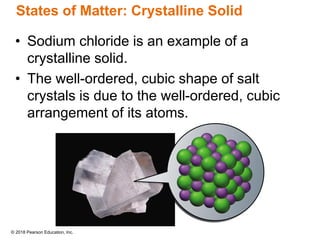

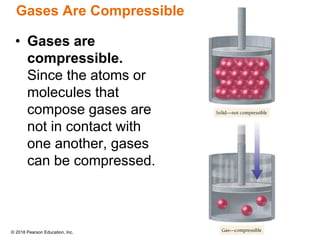

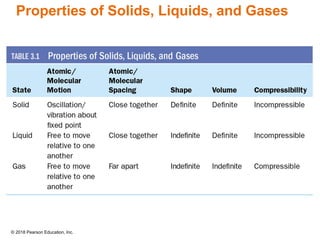

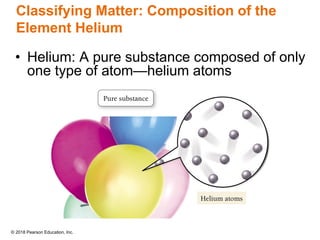

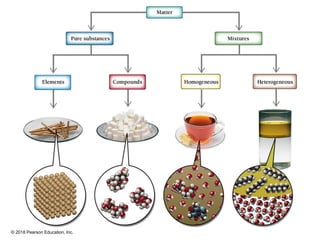

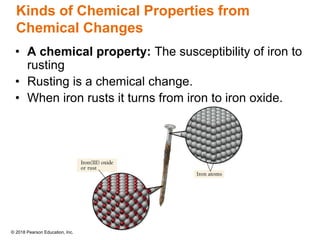

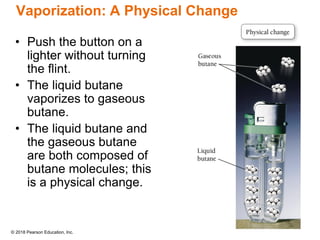

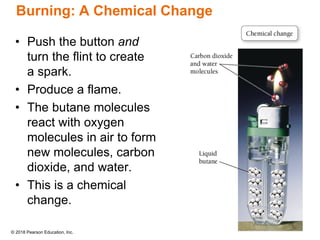

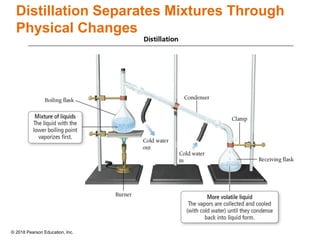

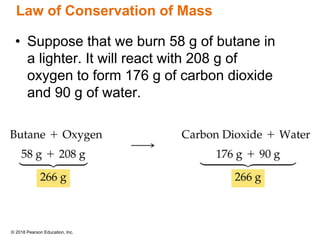

This document provides an overview of matter and its properties. It defines matter as anything that occupies space and has mass, and discusses how matter is composed of atoms and molecules. The three common states of matter are identified as solid, liquid, and gas. Physical properties are described as properties a substance displays without changing composition, while chemical properties involve a change in composition. Both physical and chemical changes are discussed.