More Related Content

PPT

PDF

PPT

ch 5 Daatabase Recovery.ppt PPTX

chapter22 Database Management Lecture Slides .pptx PDF

Database recovery techniques PDF

Chapter 7. Database Recovery Techniques.pdf PPT

Unit-V Recovery software wngineering should learn software PPT

Similar to LECTURE 11-Backup and Recovery - Dr Preeti Aggarwal.pptx

PPT

RDBMS Transactiona management from raghu ramakrishna PDF

DBMS data recovery techniques and slides pptx PDF

Database recovery techniques and slides pptx PPTX

Chapter 3 - Recogfytru6y5tfvery Techniques.pptx PPTX

fffffffChapter 1- Recovery Techniques.pptx PPTX

gyuftfChapter 1- Recovery Techniques.pptx PPTX

PPTX

PPT

DBMS UNIT 5 CHAPTER 3.ppt PPTX

PPTX

PPTX

Recovery & Atom city & Log based Recovery PPT

PPTX

Log based and Recovery with concurrent transaction PPTX

Lec 4 Recovery in database management system.pptx PPTX

Metropolis GIS System for Rishikesh City PDF

PPTX

DATABASE RECOVERY_by_aditya_singhhh.pptx PDF

Lesson12 recovery architectures PPTX

database recovery techniques More from PreetiAggarwal52

PPTX

Regression analysis and Correlation.pptx PPTX

ttest-2331bbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbbb6.pptx PPTX

RM-5 Procedure-for-Writing-a-Research-Proposal-and-Research-Report.pptx PPT

Ethicgsgfgghfhfgdhfgdhfgdfhhhjhhjs-2.ppt PPT

2. Dependeccnt_Independent Variables.ppt PPTX

Thesis Ivvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvvntro.pptx PPT

Siddu_RegiocccccccccccccccccnGrowing.ppt PPT

EE 583-Lectursssse1sffgdhfdhgdhfdfdg0.ppt PPTX

ERD_to_Rel2.PPThhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh.pptx PPT

Lecture10-File Systems-PAfgfgfgfgfgfgf.ppt PPT

Lecture12-Secondary Storage-PAhsjfhsjf.ppt Recently uploaded

PPTX

Pig- piggy bank in Big Data Analytics.ppt.pptx PPTX

AN EXTREMELY BORING GENERAL QUIZ FOR UG.pptx PPTX

Overview of how to Create a Model in Odoo 18 PPTX

4 G8_Q3_L4 (Evaluating opinion editorials for textual evidence and quality).pptx PPTX

META-ANALYSIS INTERPRETATION, PUBLICATION BIAS AND GRADE ASSESSMENT.pptx PPTX

PURPOSIVE SAMPLING IN EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH RACHITHRA RK.pptx PPTX

Repeat Orders_ Use Odoo Blanket Agreement PPTX

ATTENTION -PART 2.pptx Shilpa Hotakar for I semester BSc students PDF

Cultivating Greatness Pune's Best Preschools and Schools.pdf PPTX

Details of Epithelial and Connective Tissue.pptx PPTX

Planning Assessment for Outcome-based Education PPTX

REVISED DEFENSE MECHANISM / ADJUSTMENT MECHANISM-FINAL PPTX

Basics in Phytochemistry, Extraction, Isolation methods, Characterisation etc. PDF

International Men's Day Event: Breaking the Silence: Embracing Vulnerability ... PDF

Most Imp Chapters & Weightage for Boards 2025.pdf PDF

Risk management in Moroccan public hospitals_ a literature review PPTX

3 G8_Q3_L3_ (Cartoon as Representation in Opinion Editorial Article).pptx PDF

M.Sc. Nonchordates Complete Syllabus PPT | All Important Topics Covered PDF

Multiple Myeloma , definition, etiology, PP, CM , DE and management PDF

Scalable-MADDPG-Based Cooperative Target Invasion for a Multi-USV System.pdf LECTURE 11-Backup and Recovery - Dr Preeti Aggarwal.pptx

- 1.

- 2.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

Database Recovery Techniques

- 3.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 3

Outline

Databases Recovery

1. Purpose of Database Recovery

2. Types of Failure

3 . Transaction Log

4 . Data Updates

5. Data Caching

6 . Transaction Roll-back (Undo) and Roll-Forward

7 . Checkpointing

8 . Recovery schemes

9 . ARIES Recovery Scheme

10. Recovery in Multidatabase System

- 4.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 4

Database Recovery

1 Purpose of Database Recovery

To bring the database into the last consistent state,

which existed prior to the failure.

To preserve transaction properties (Atomicity,

Consistency, Isolation and Durability).

Example:

If the system crashes before a fund transfer

transaction completes its execution, then either one or

both accounts may have incorrect value. Thus, the

database must be restored to the state before the

transaction modified any of the accounts.

- 5.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 5

Database Recovery

2 Types of Failure

The database may become unavailable for use due to

Transaction failure: Transactions may fail because of

incorrect input, deadlock, incorrect synchronization.

a) Logical errors: transaction cannot complete due to some

internal error condition

b) System errors: the database system must terminate an active

transaction due to an error condition (e.g., deadlock)

System failure: System may fail because of addressing error,

application error, power failure, operating system fault, RAM

failure, etc.

Media failure: Disk head crash, power disruption, etc.

- 6.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

Failure Classification Concluded

Types of failures

1. Transaction failure

Erroneous parameter values

Logical programming error

System error like integer overflow, division by zero

Local error like “data not found”

User interrupt

Concurrency control enforcement

2. Malicious transaction

3. System crash

A hardware, software, or network

4. Disk failure

- 7.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

Recovery and Atomicity

To ensure atomicity despite failures, we first output information describing the

modifications to stable storage without modifying the database itself.

We study two approaches:

log-based recovery, Two approaches using logs

Deferred database modification

Immediate database modification

And

shadow-paging

We assume (initially) that transactions run serially, that is, one after the other.

- 8.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 8

Database Recovery

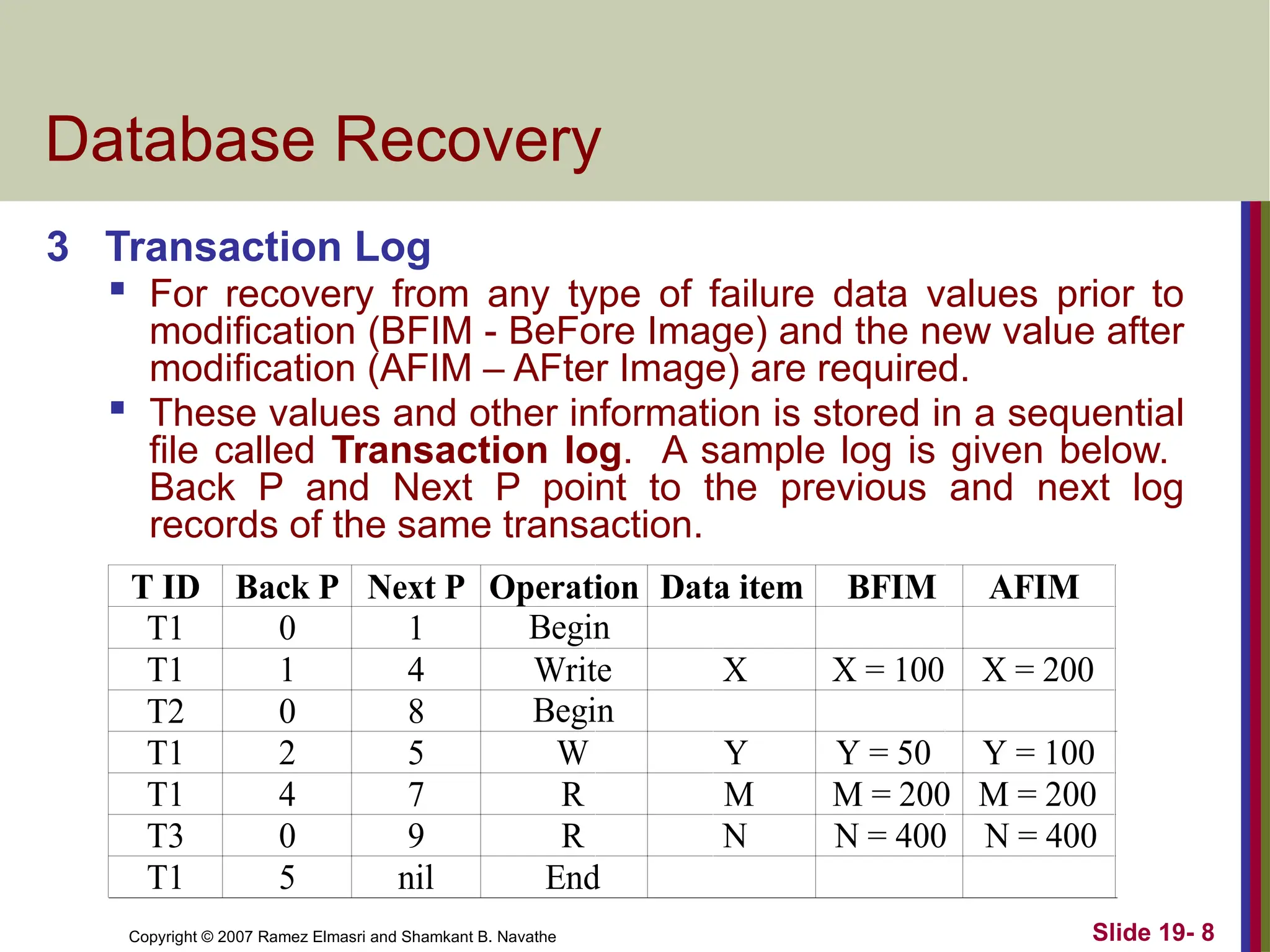

3 Transaction Log

For recovery from any type of failure data values prior to

modification (BFIM - BeFore Image) and the new value after

modification (AFIM – AFter Image) are required.

These values and other information is stored in a sequential

file called Transaction log. A sample log is given below.

Back P and Next P point to the previous and next log

records of the same transaction.

T ID Back P Next P Operation Data item BFIM AFIM

T1 0 1

T1 1 4

T2 0 8

T1 2 5

T1 4 7

T3 0 9

T1 5 nil

Begin

Write

W

R

R

End

Begin

X

Y

M

N

X = 200

Y = 100

M = 200

N = 400

X = 100

Y = 50

M = 200

N = 400

- 9.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 9

Database Recovery

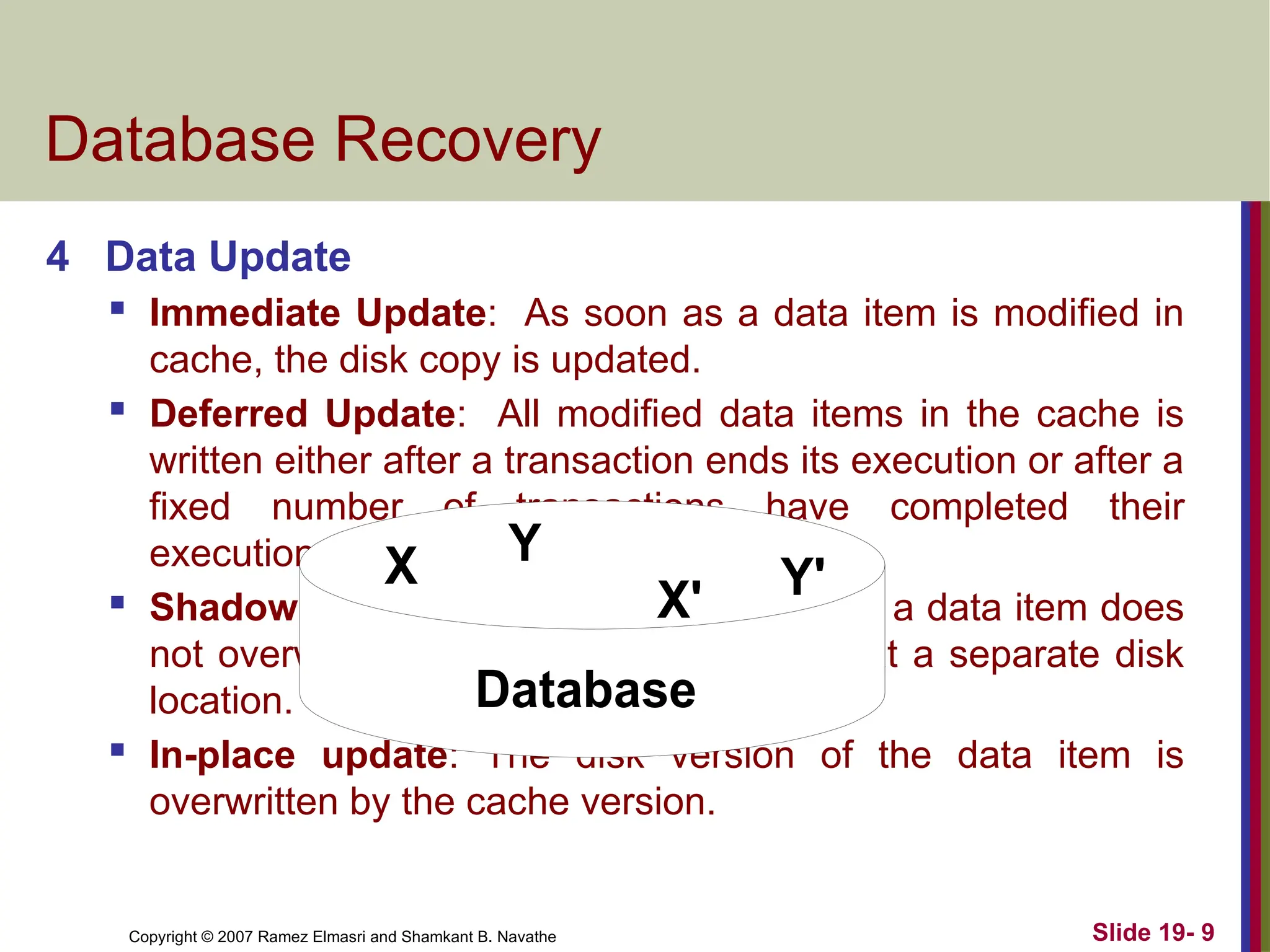

4 Data Update

Immediate Update: As soon as a data item is modified in

cache, the disk copy is updated.

Deferred Update: All modified data items in the cache is

written either after a transaction ends its execution or after a

fixed number of transactions have completed their

execution.

Shadow update: The modified version of a data item does

not overwrite its disk copy but is written at a separate disk

location.

In-place update: The disk version of the data item is

overwritten by the cache version.

X Y

Database

X' Y'

- 10.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 10

Database Recovery

5 Data Caching

Data items to be modified are first stored into

database cache by the Cache Manager (CM) and

after modification they are flushed (written) to the

disk.

The flushing is controlled by Modified and Pin-

Unpin bits.

Pin-Unpin: Instructs the operating system not to

flush the data item.

Modified: Indicates the AFIM of the data item.

- 11.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 11

Database Recovery

6 Transaction Roll-back (Undo) and Roll-

Forward (Redo)

To maintain atomicity, a transaction’s operations

are redone or undone.

Undo: Restore all BFIMs on to disk (Remove all

AFIMs).

Redo: Restore all AFIMs on to disk.

Database recovery is achieved either by

performing only Undos or only Redos or by a

combination of the two. These operations are

recorded in the log as they happen.

- 12.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 12

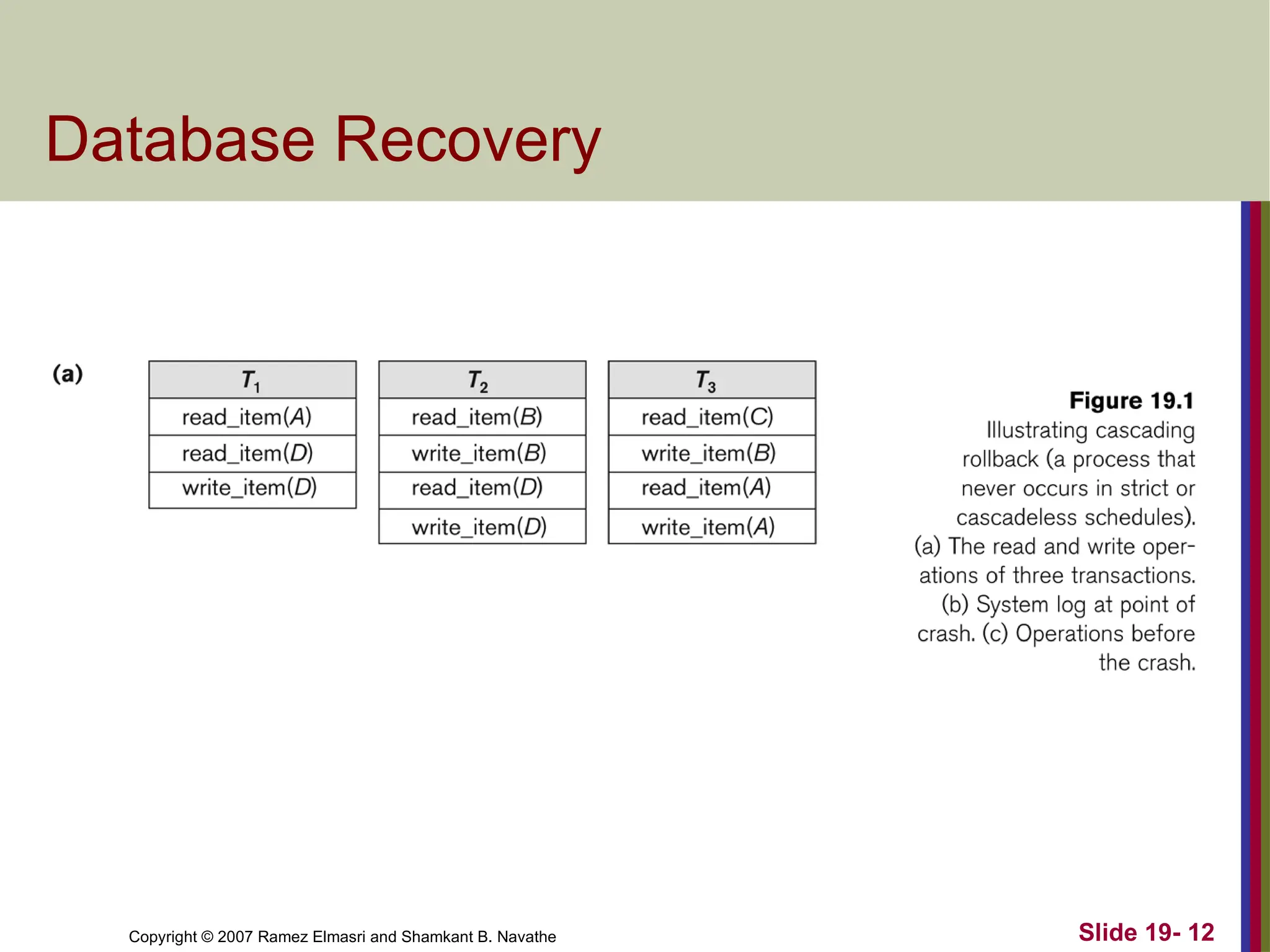

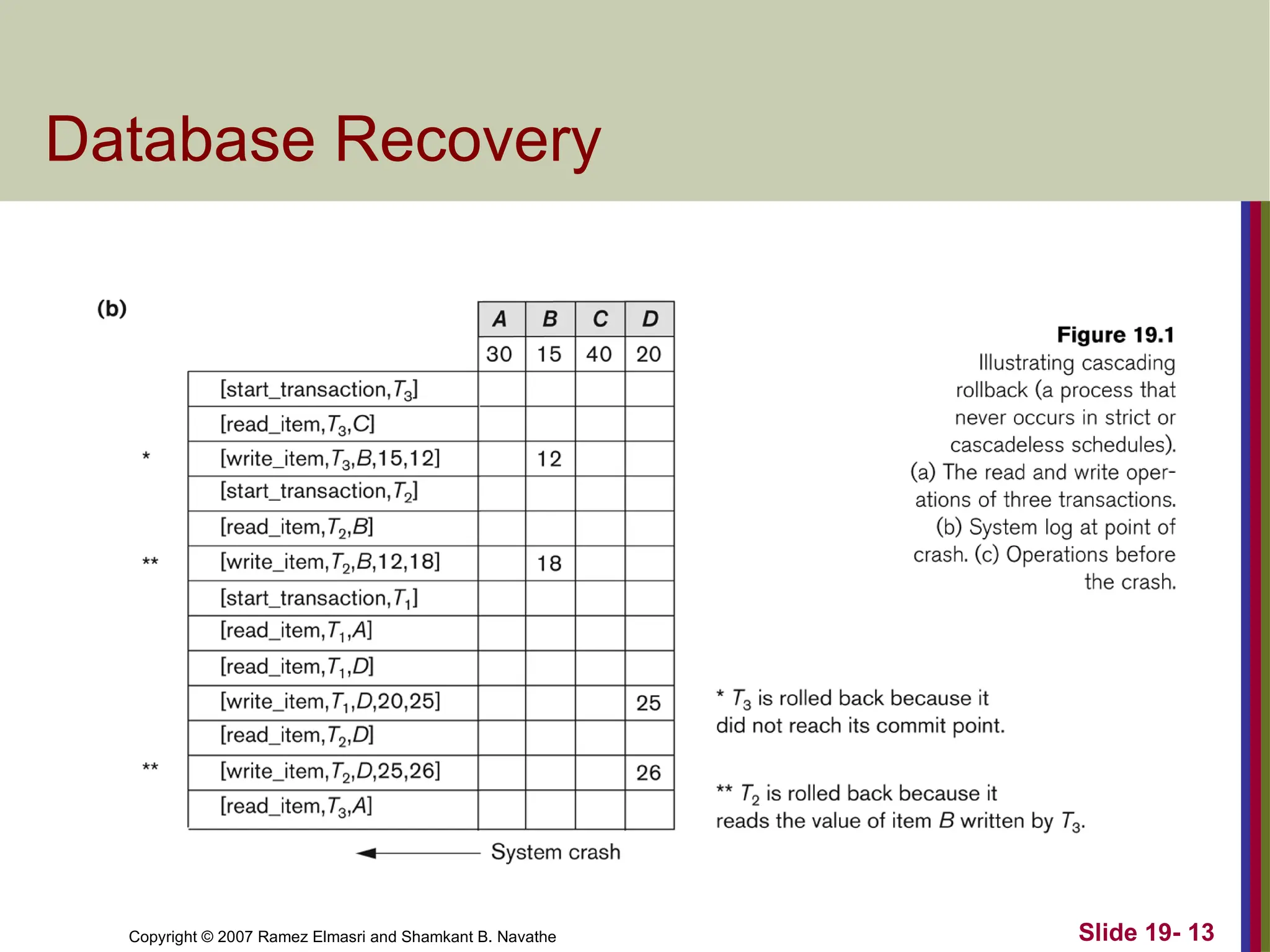

Database Recovery

- 13.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 13

Database Recovery

- 14.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 14

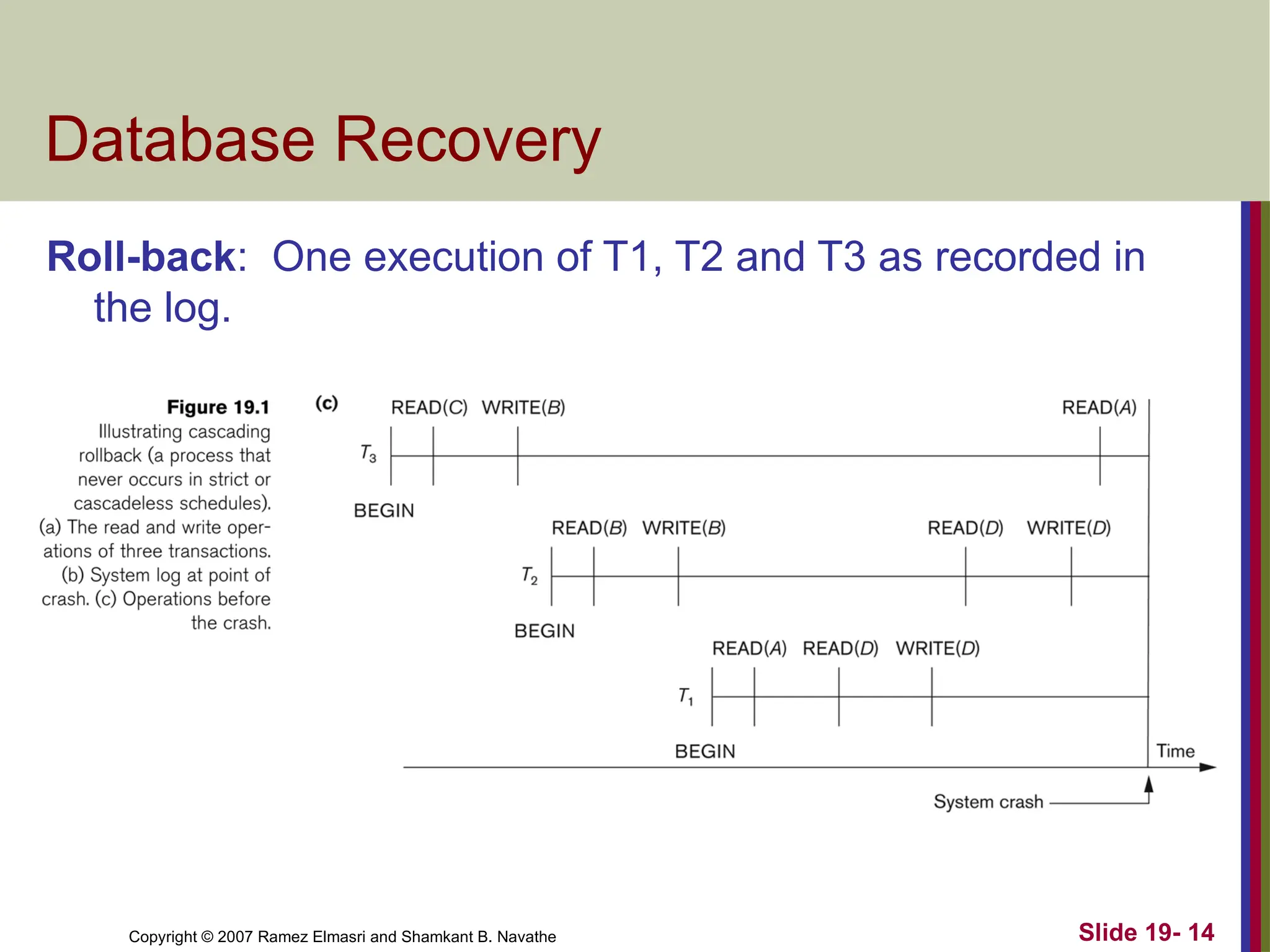

Database Recovery

Roll-back: One execution of T1, T2 and T3 as recorded in

the log.

- 15.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 15

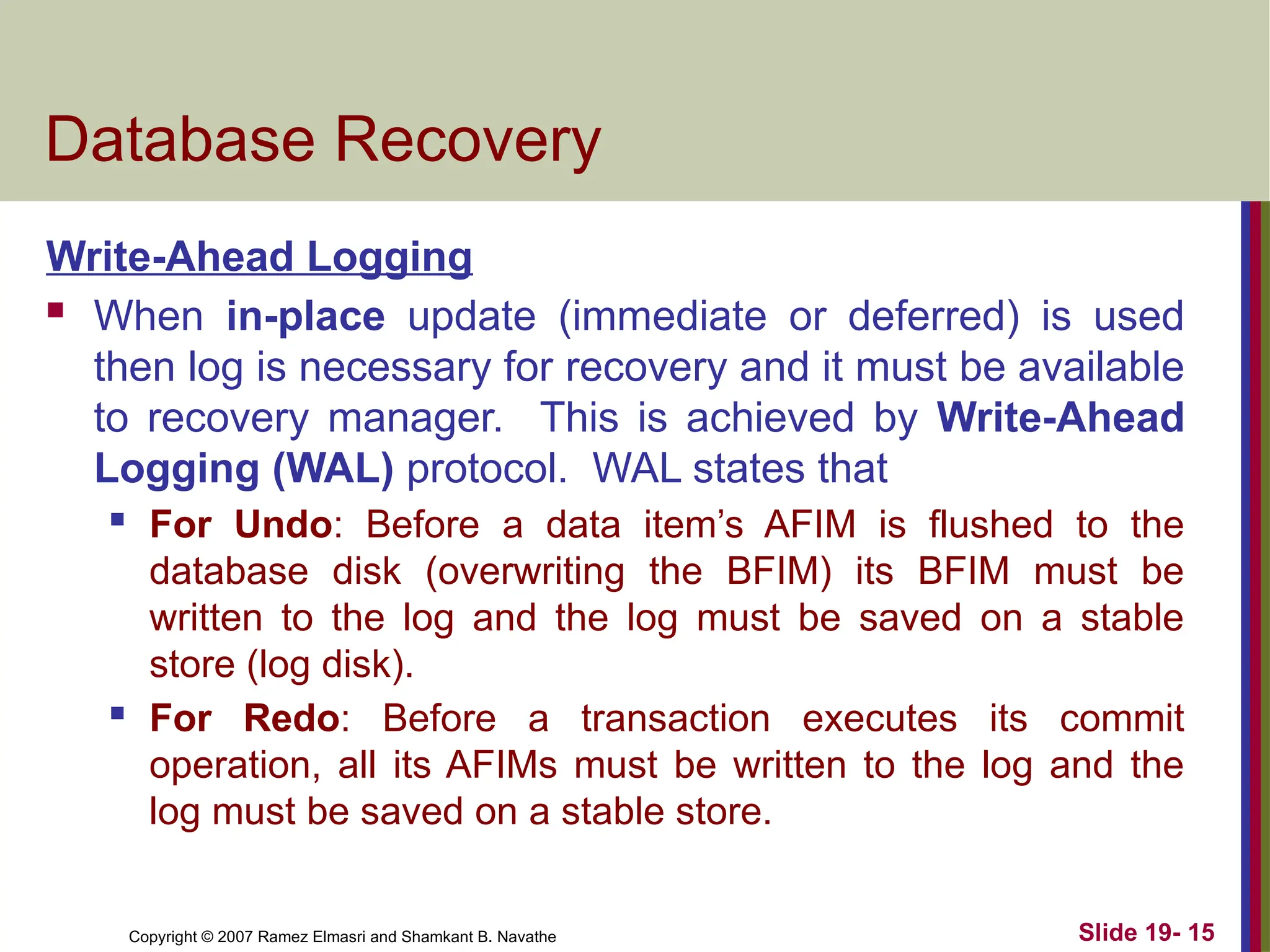

Database Recovery

Write-Ahead Logging

When in-place update (immediate or deferred) is used

then log is necessary for recovery and it must be available

to recovery manager. This is achieved by Write-Ahead

Logging (WAL) protocol. WAL states that

For Undo: Before a data item’s AFIM is flushed to the

database disk (overwriting the BFIM) its BFIM must be

written to the log and the log must be saved on a stable

store (log disk).

For Redo: Before a transaction executes its commit

operation, all its AFIMs must be written to the log and the

log must be saved on a stable store.

- 16.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

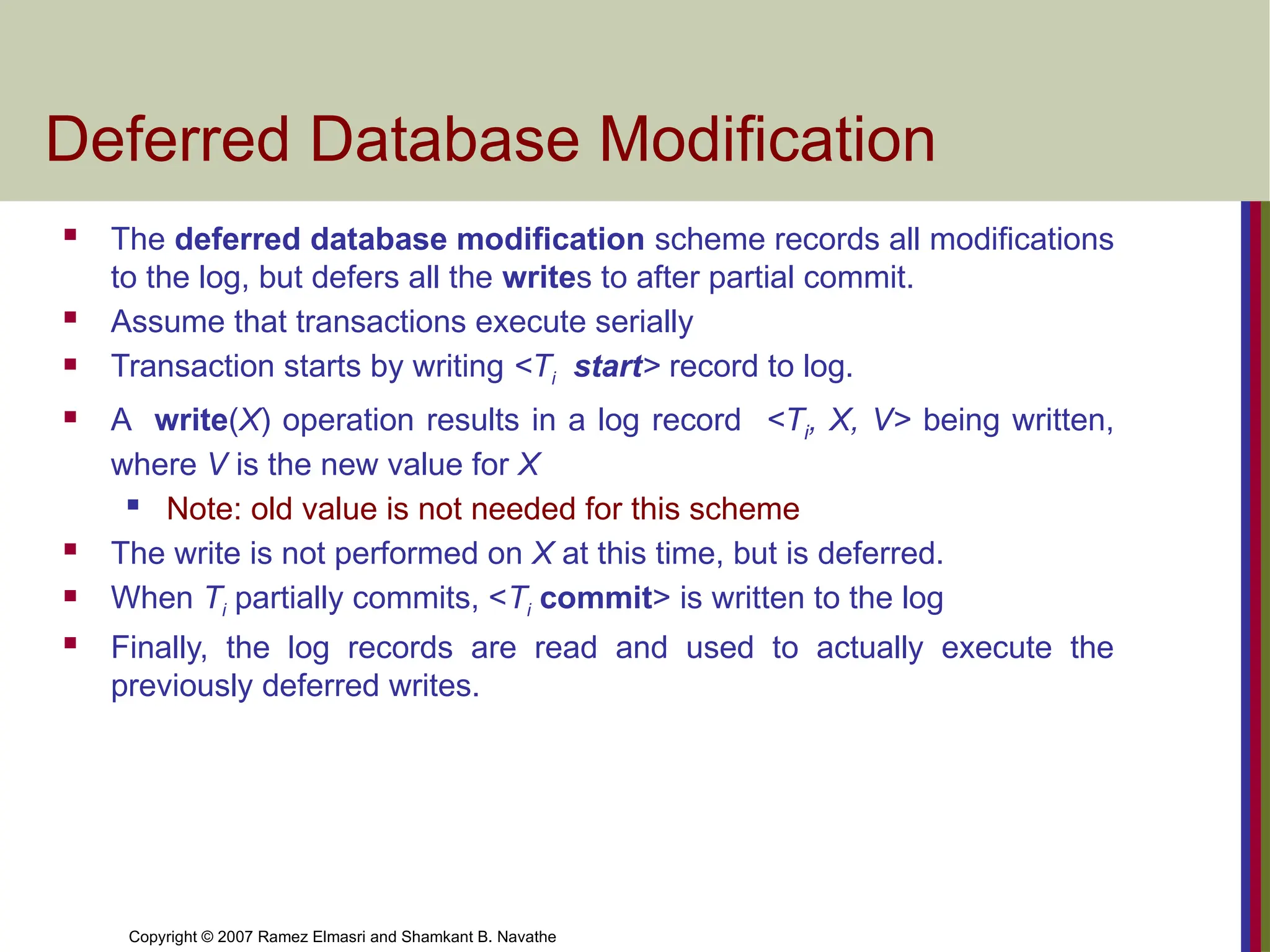

Deferred Database Modification

The deferred database modification scheme records all modifications

to the log, but defers all the writes to after partial commit.

Assume that transactions execute serially

Transaction starts by writing <Ti start> record to log.

A write(X) operation results in a log record <Ti, X, V> being written,

where V is the new value for X

Note: old value is not needed for this scheme

The write is not performed on X at this time, but is deferred.

When Ti partially commits, <Ti commit> is written to the log

Finally, the log records are read and used to actually execute the

previously deferred writes.

- 17.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

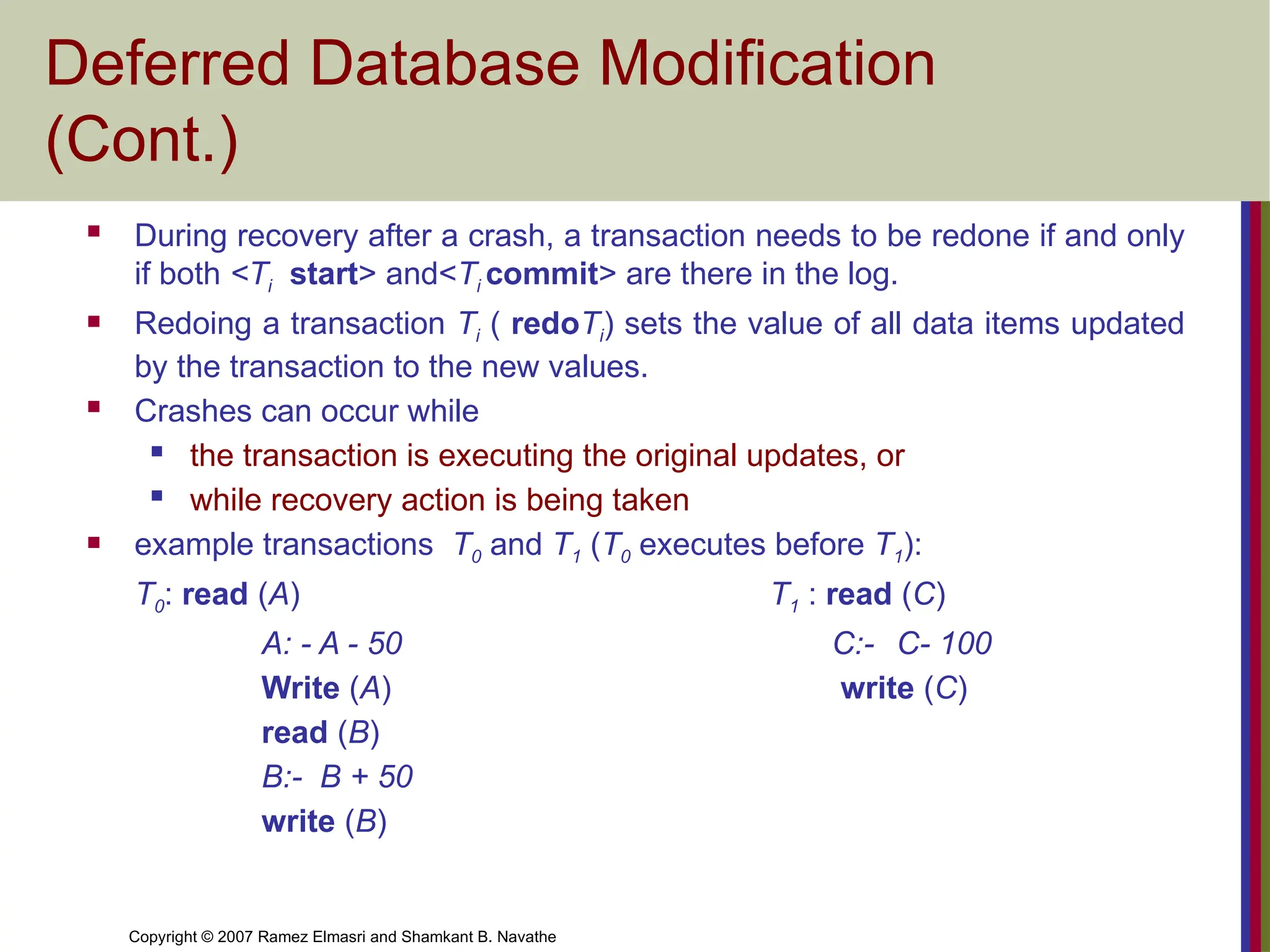

Deferred Database Modification

(Cont.)

During recovery after a crash, a transaction needs to be redone if and only

if both <Ti start> and<Ti commit> are there in the log.

Redoing a transaction Ti ( redoTi) sets the value of all data items updated

by the transaction to the new values.

Crashes can occur while

the transaction is executing the original updates, or

while recovery action is being taken

example transactions T0 and T1 (T0 executes before T1):

T0: read (A) T1 : read (C)

A: - A - 50 C:- C- 100

Write (A) write (C)

read (B)

B:- B + 50

write (B)

- 18.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

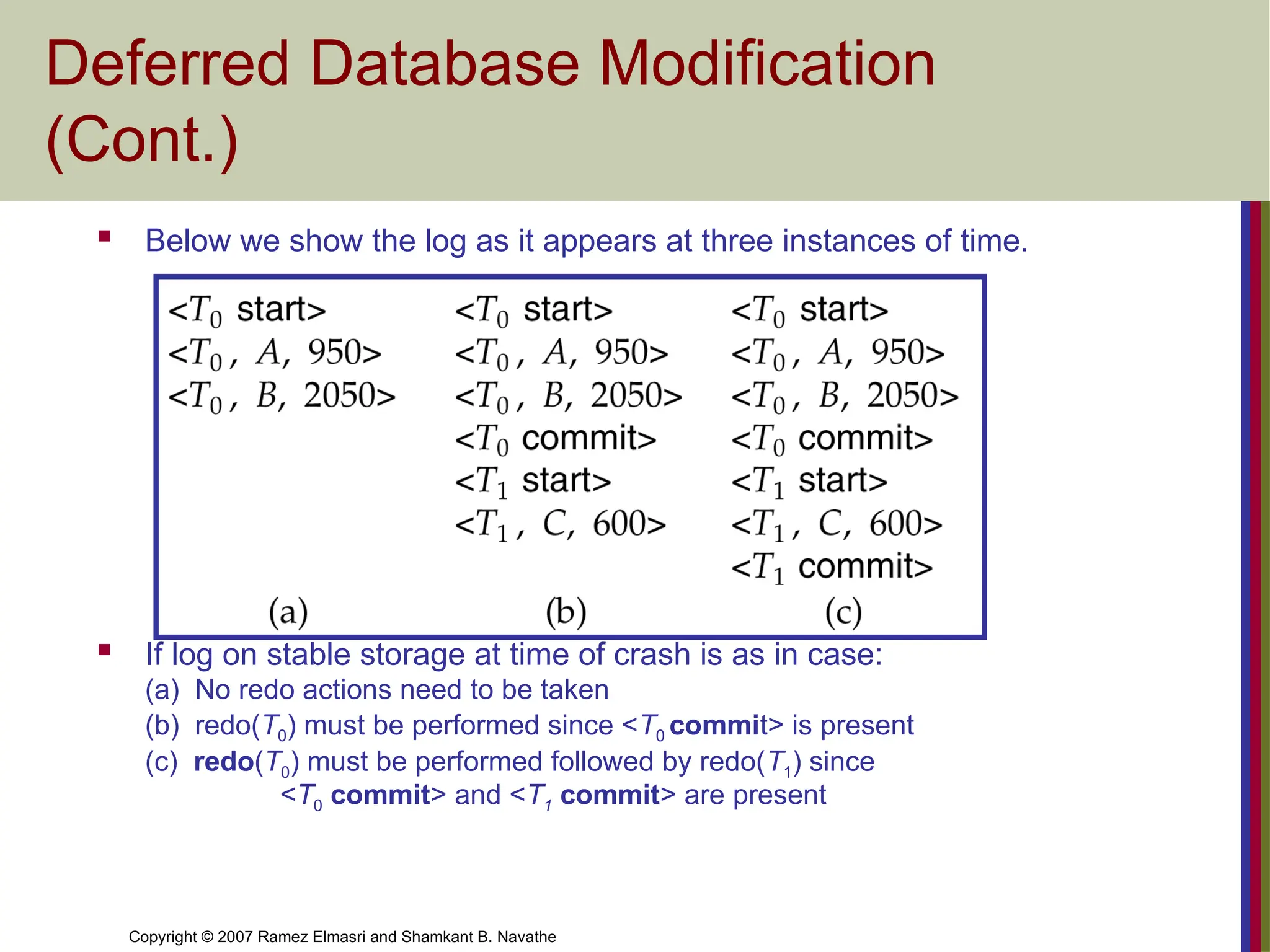

Deferred Database Modification

(Cont.)

Below we show the log as it appears at three instances of time.

If log on stable storage at time of crash is as in case:

(a) No redo actions need to be taken

(b) redo(T0) must be performed since <T0 commit> is present

(c) redo(T0) must be performed followed by redo(T1) since

<T0 commit> and <T1 commit> are present

- 19.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

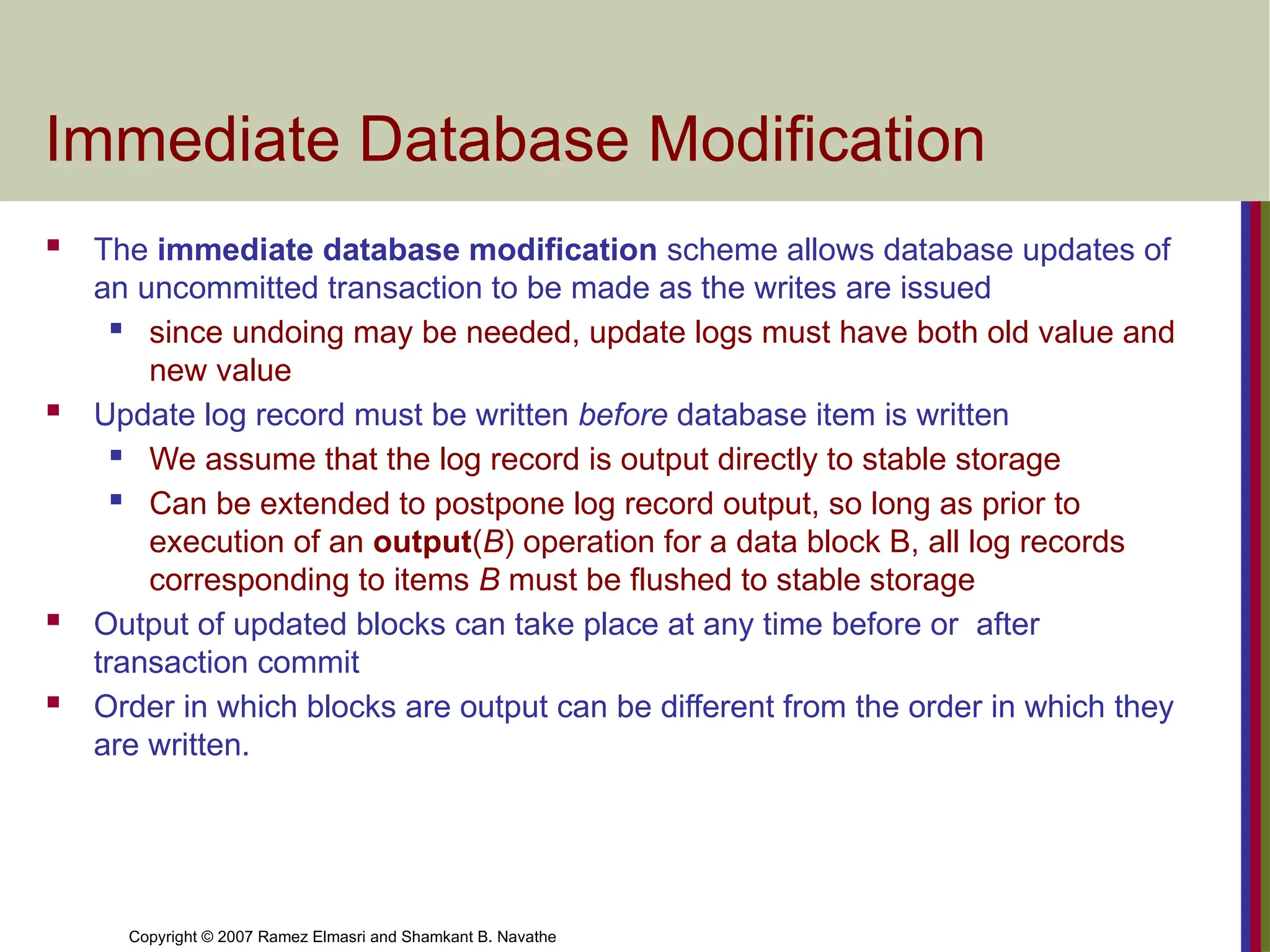

Immediate Database Modification

The immediate database modification scheme allows database updates of

an uncommitted transaction to be made as the writes are issued

since undoing may be needed, update logs must have both old value and

new value

Update log record must be written before database item is written

We assume that the log record is output directly to stable storage

Can be extended to postpone log record output, so long as prior to

execution of an output(B) operation for a data block B, all log records

corresponding to items B must be flushed to stable storage

Output of updated blocks can take place at any time before or after

transaction commit

Order in which blocks are output can be different from the order in which they

are written.

- 20.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

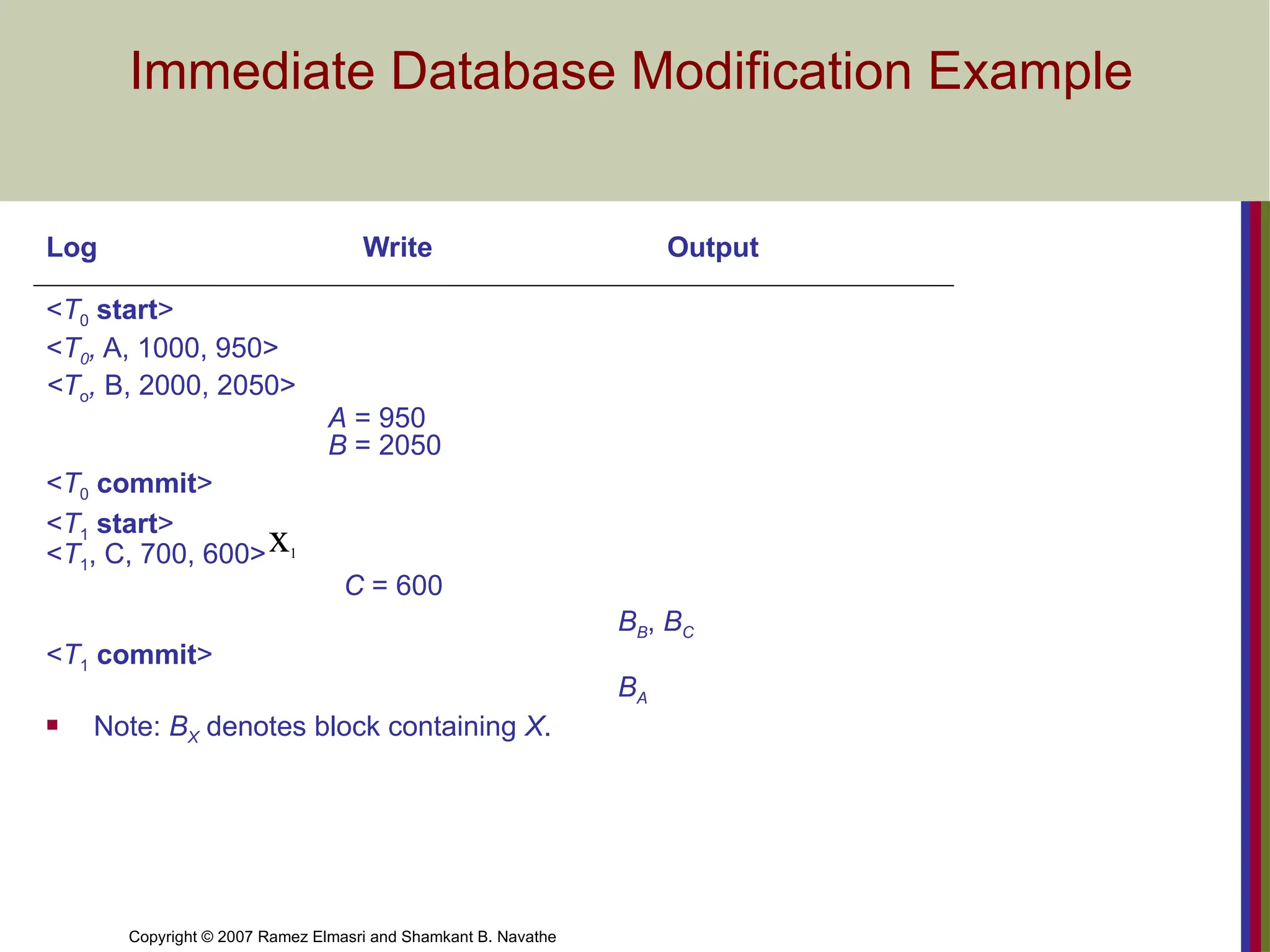

Immediate Database Modification Example

Log Write Output

<T0 start>

<T0, A, 1000, 950>

<To, B, 2000, 2050>

A = 950

B = 2050

<T0 commit>

<T1 start>

<T1, C, 700, 600>

C = 600

BB, BC

<T1 commit>

BA

Note: BX denotes block containing X.

x1

- 21.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

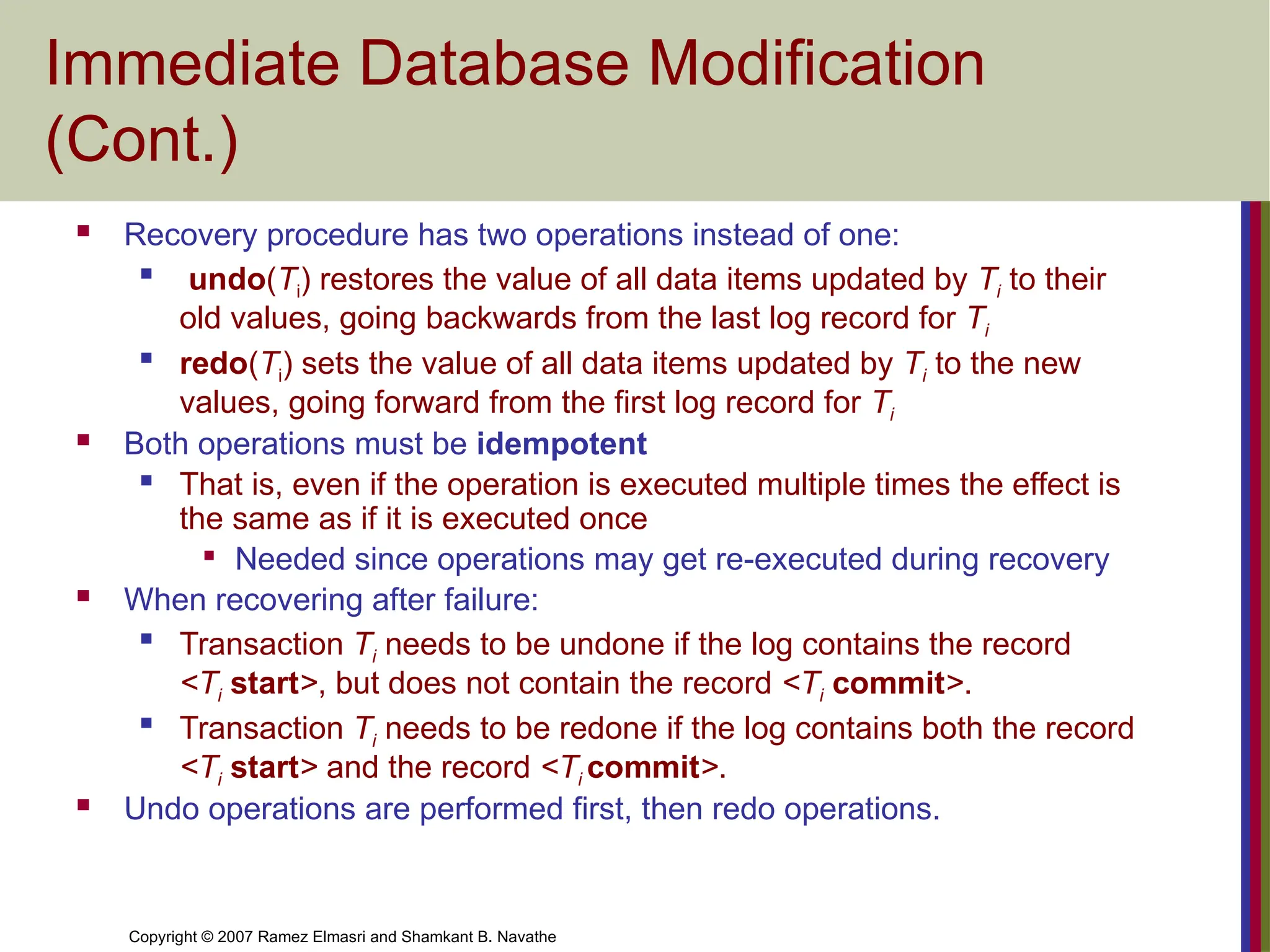

Immediate Database Modification

(Cont.)

Recovery procedure has two operations instead of one:

undo(Ti) restores the value of all data items updated by Ti to their

old values, going backwards from the last log record for Ti

redo(Ti) sets the value of all data items updated by Ti to the new

values, going forward from the first log record for Ti

Both operations must be idempotent

That is, even if the operation is executed multiple times the effect is

the same as if it is executed once

Needed since operations may get re-executed during recovery

When recovering after failure:

Transaction Ti needs to be undone if the log contains the record

<Ti start>, but does not contain the record <Ti commit>.

Transaction Ti needs to be redone if the log contains both the record

<Ti start> and the record <Ti commit>.

Undo operations are performed first, then redo operations.

- 22.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

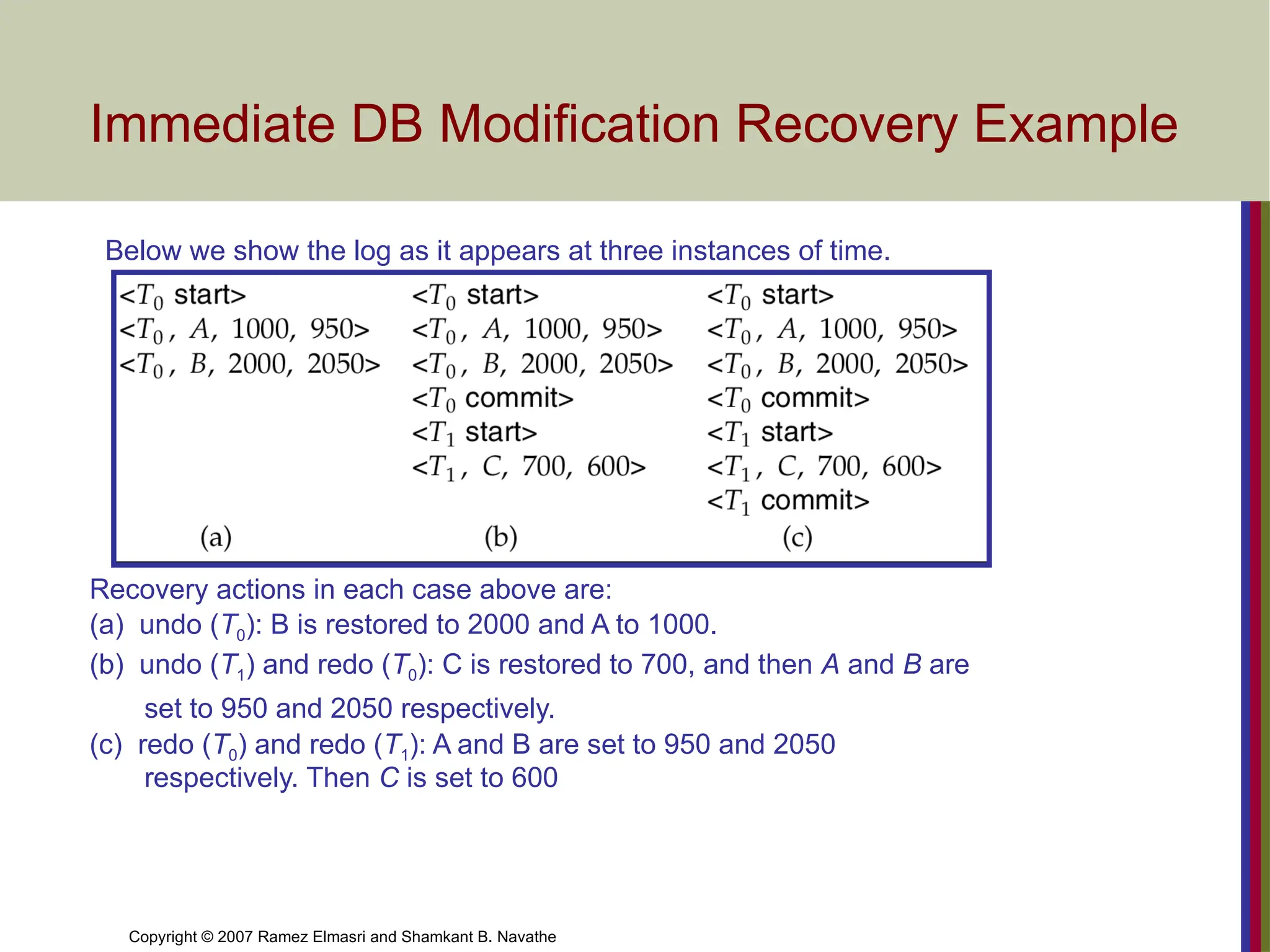

Immediate DB Modification Recovery Example

Below we show the log as it appears at three instances of time.

Recovery actions in each case above are:

(a) undo (T0): B is restored to 2000 and A to 1000.

(b) undo (T1) and redo (T0): C is restored to 700, and then A and B are

set to 950 and 2050 respectively.

(c) redo (T0) and redo (T1): A and B are set to 950 and 2050

respectively. Then C is set to 600

- 23.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 23

Database Recovery

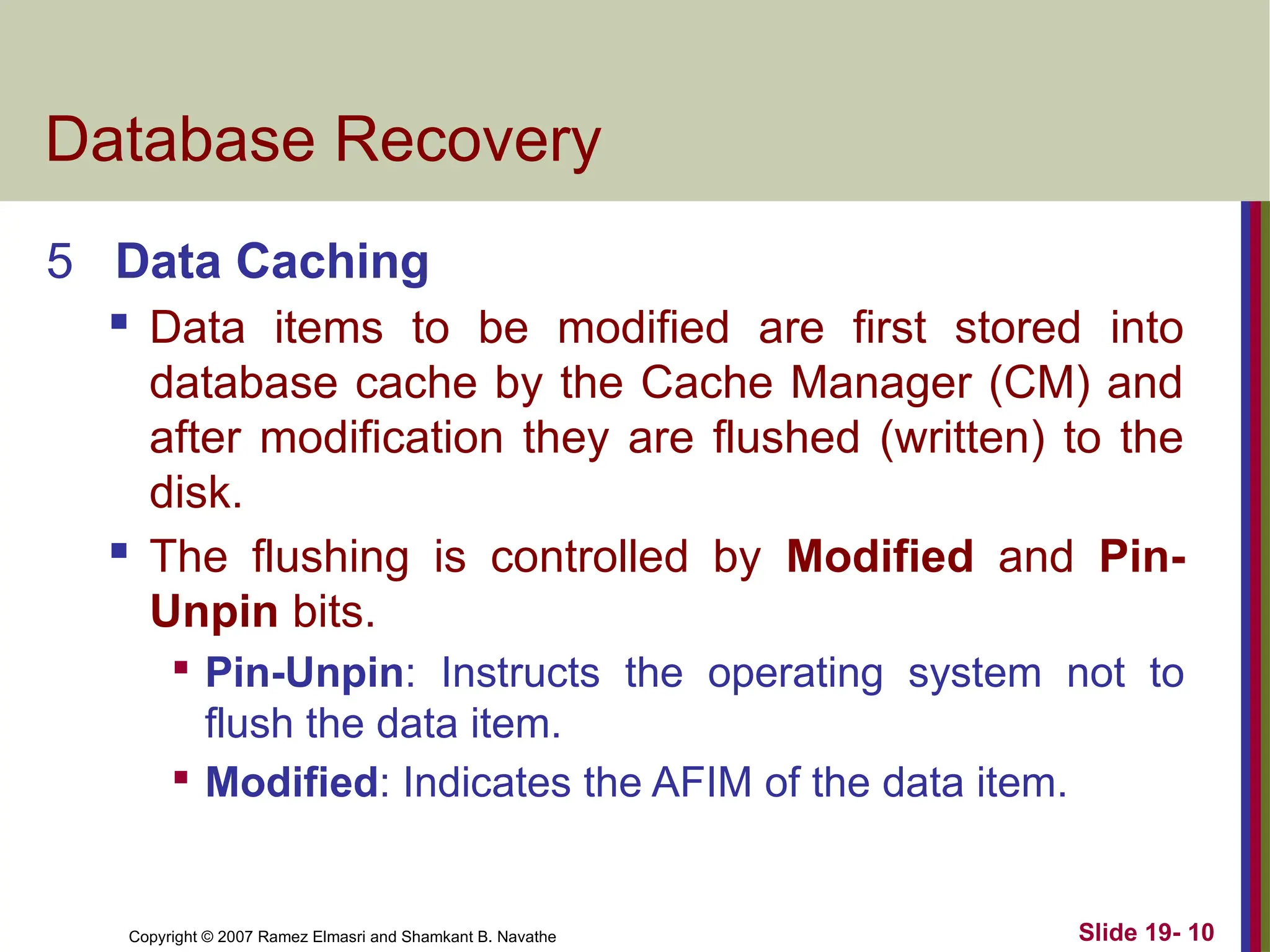

7 Checkpointing

Time to time (randomly or under some criteria) the

database flushes its buffer to database disk to minimize

the task of recovery. The following steps defines a

checkpoint operation:

1. Suspend execution of transactions temporarily.

2. Force write modified buffer data to disk.

3. Write a [checkpoint] record to the log, save the log to disk.

4. Resume normal transaction execution.

During recovery redo or undo is required to transactions

appearing after [checkpoint] record.

- 24.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

Checkpoints

Problems in recovery procedure as discussed earlier :

1. searching the entire log is time-consuming

2. we might unnecessarily redo transactions which have already output

their updates to the database.

Streamline recovery procedure by periodically performing checkpointing

1. Output all log records currently residing in main memory onto stable

storage.

2. Output all modified buffer blocks to the disk.

3. Write a log record < checkpoint> onto stable storage.

- 25.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

Checkpoints (Cont.)

During recovery we need to consider only the most recent transaction Ti that

started before the checkpoint, and transactions that started after Ti.

1. Scan backwards from end of log to find the most recent <checkpoint>

record

2. Continue scanning backwards till a record <Ti start> is found.

3. Need only consider the part of log following above start record. Earlier

part of log can be ignored during recovery, and can be erased whenever

desired.

4. For all transactions (starting from Ti or later) with no <Ti commit>,

execute undo(Ti). (Done only in case of immediate modification.)

5. Scanning forward in the log, for all transactions starting from Ti or

later with a <Ti commit>, execute redo(Ti).

- 26.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

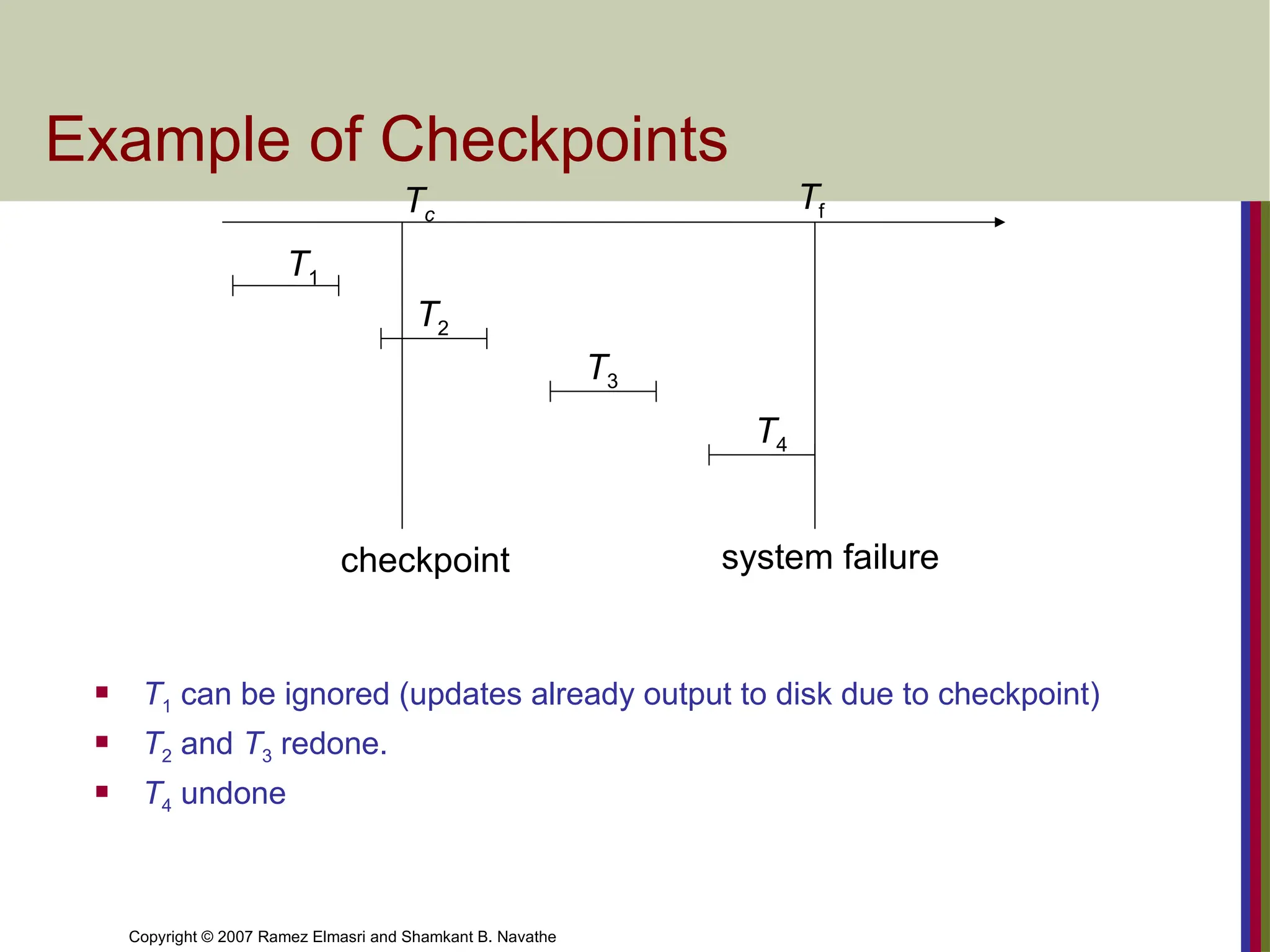

Example of Checkpoints

T1 can be ignored (updates already output to disk due to checkpoint)

T2 and T3 redone.

T4 undone

Tc

Tf

T1

T2

T3

T4

checkpoint system failure

- 27.

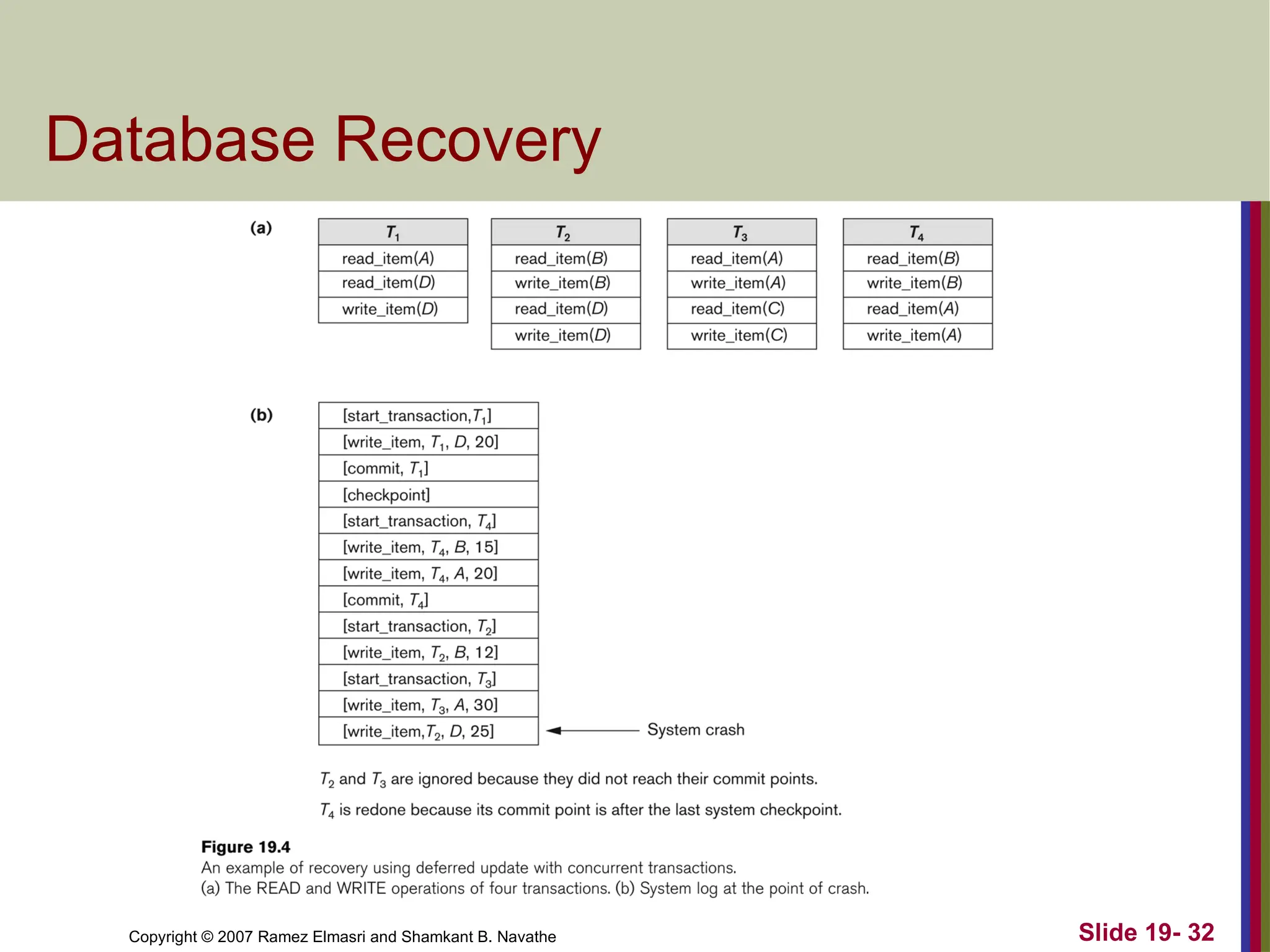

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 31

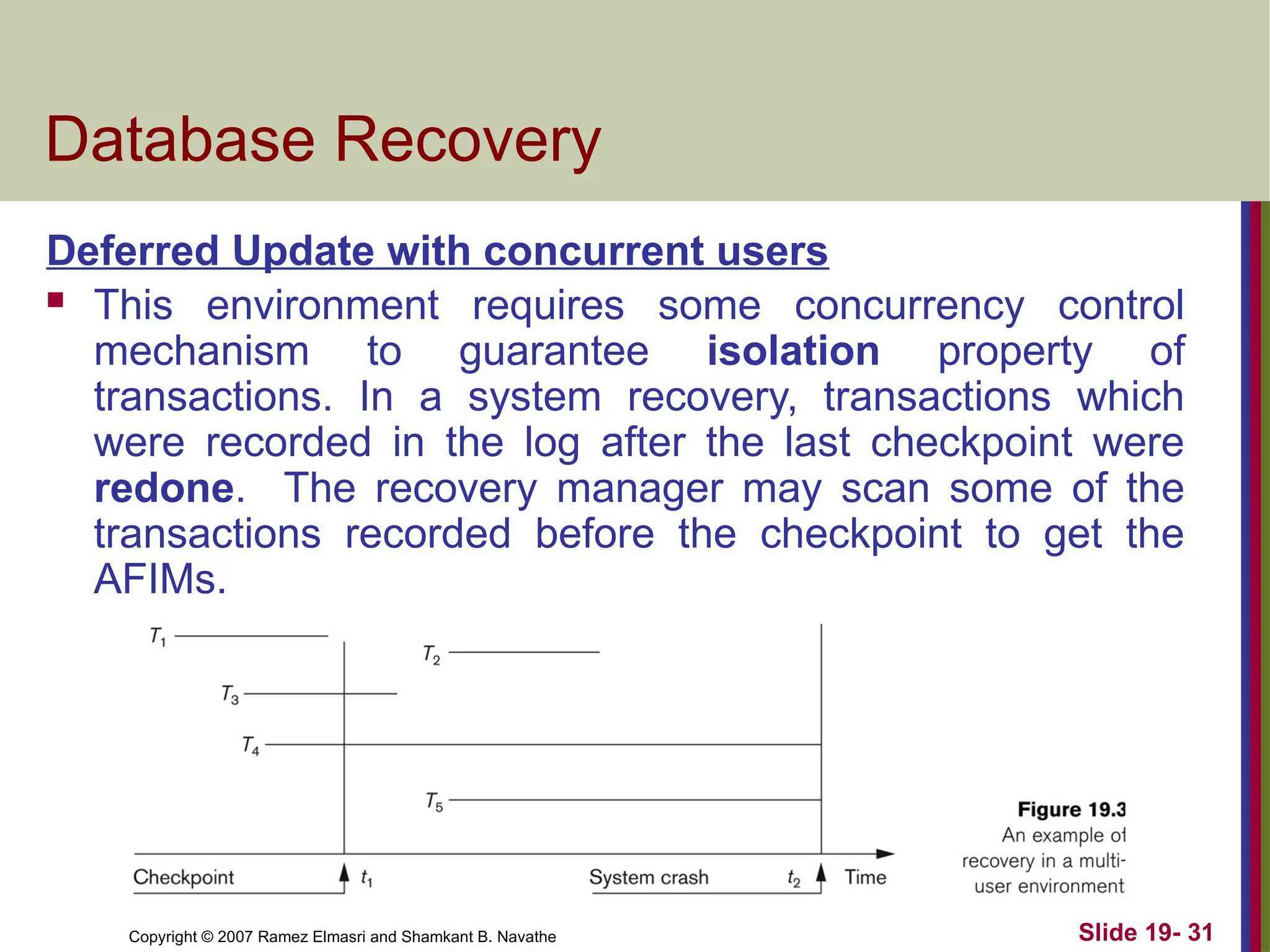

Database Recovery

Deferred Update with concurrent users

This environment requires some concurrency control

mechanism to guarantee isolation property of

transactions. In a system recovery, transactions which

were recorded in the log after the last checkpoint were

redone. The recovery manager may scan some of the

transactions recorded before the checkpoint to get the

AFIMs.

- 28.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 32

Database Recovery

- 29.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 33

Database Recovery

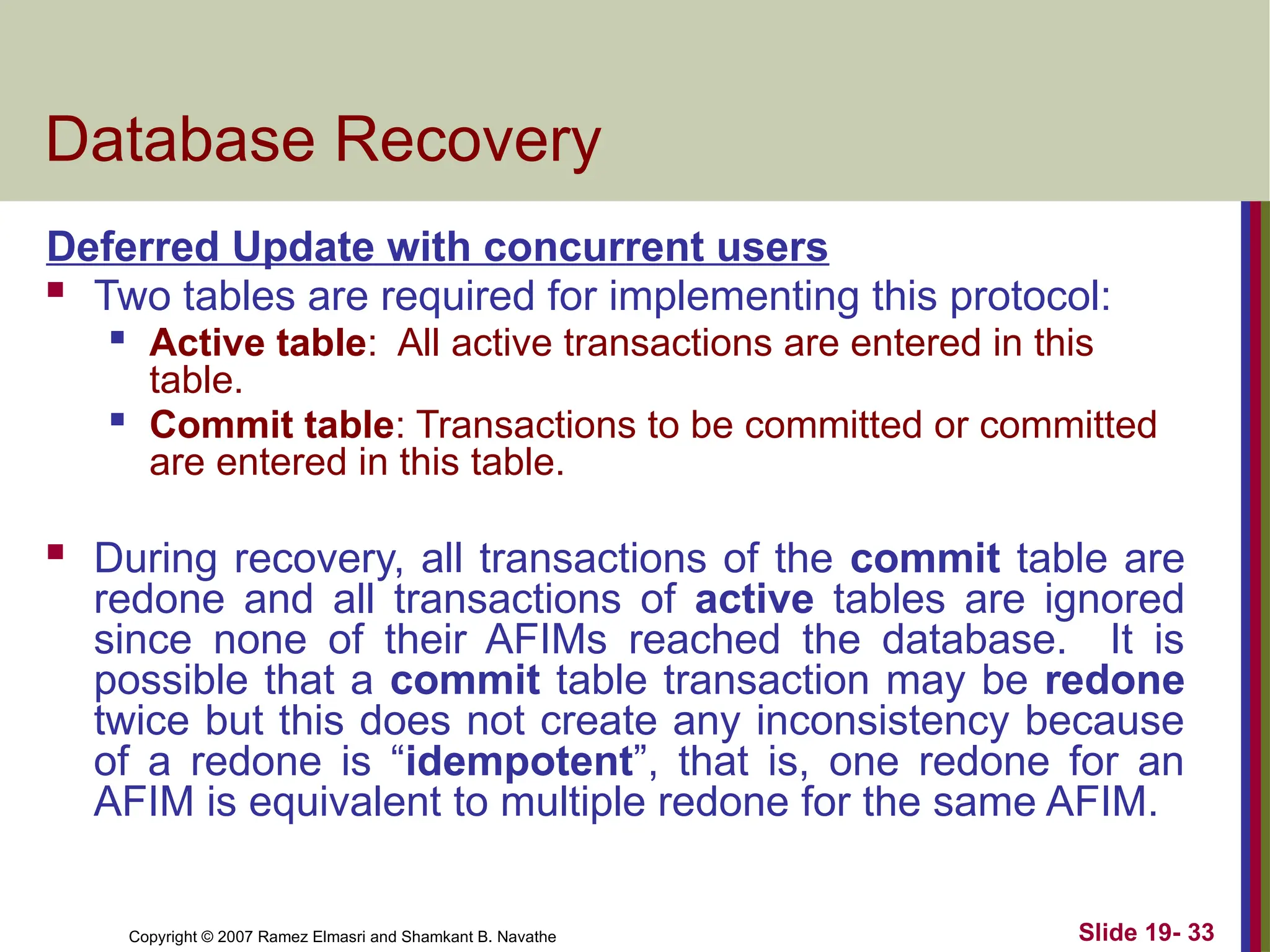

Deferred Update with concurrent users

Two tables are required for implementing this protocol:

Active table: All active transactions are entered in this

table.

Commit table: Transactions to be committed or committed

are entered in this table.

During recovery, all transactions of the commit table are

redone and all transactions of active tables are ignored

since none of their AFIMs reached the database. It is

possible that a commit table transaction may be redone

twice but this does not create any inconsistency because

of a redone is “idempotent”, that is, one redone for an

AFIM is equivalent to multiple redone for the same AFIM.

- 30.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 37

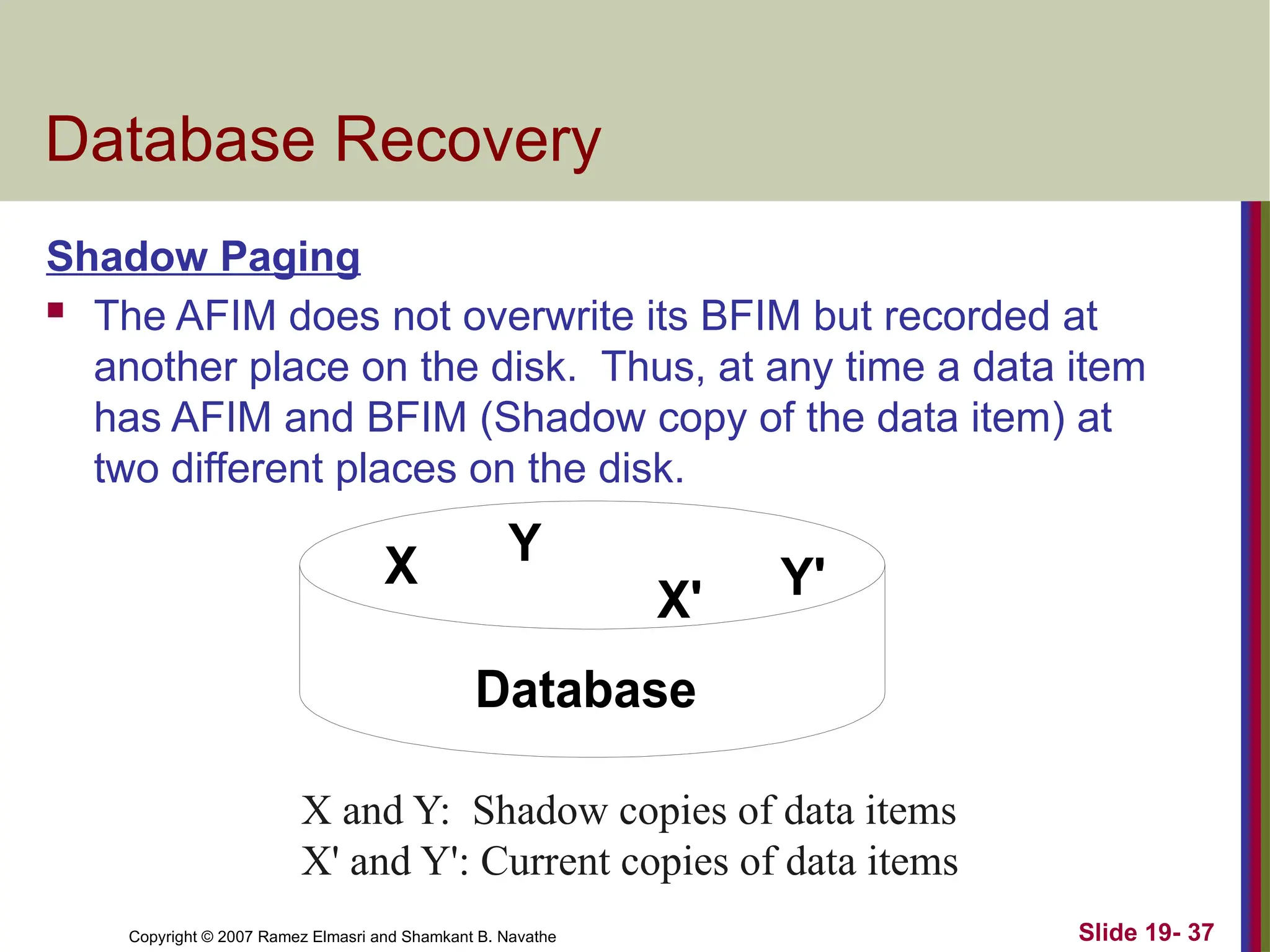

Database Recovery

Shadow Paging

The AFIM does not overwrite its BFIM but recorded at

another place on the disk. Thus, at any time a data item

has AFIM and BFIM (Shadow copy of the data item) at

two different places on the disk.

X Y

Database

X' Y'

X and Y: Shadow copies of data items

X' and Y': Current copies of data items

- 31.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 38

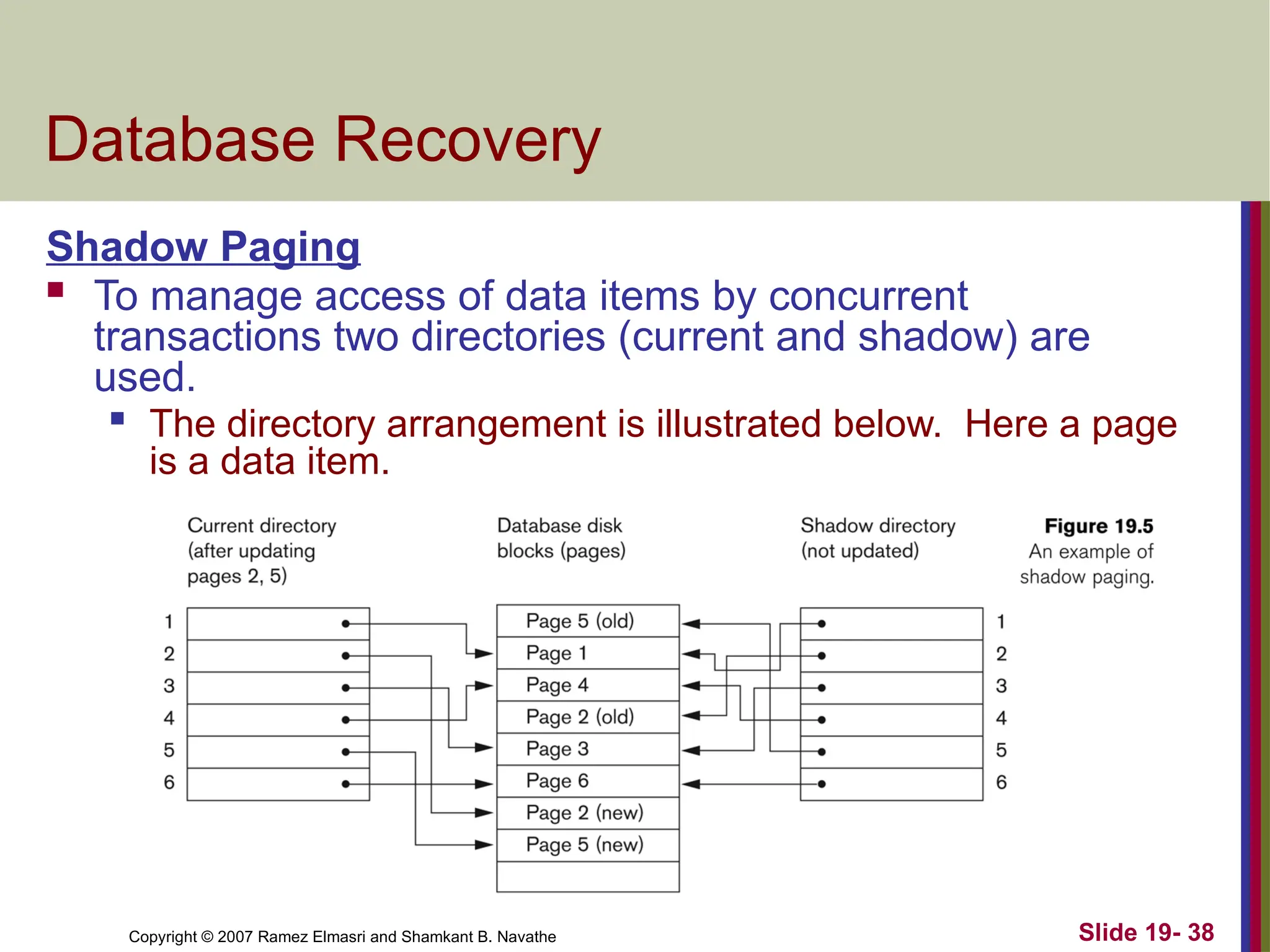

Database Recovery

Shadow Paging

To manage access of data items by concurrent

transactions two directories (current and shadow) are

used.

The directory arrangement is illustrated below. Here a page

is a data item.

- 32.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

Shadow Paging

Shadow paging is an alternative to log-based recovery; this

scheme is useful if transactions execute serially

Idea: maintain two page tables during the lifetime of a transaction –

the current page table, and the shadow page table

Store the shadow page table in nonvolatile storage, such that state

of the database prior to transaction execution may be recovered.

Shadow page table is never modified during execution

To start with, both the page tables are identical. Only current page

table is used for data item accesses during execution of the

transaction.

Whenever any page is about to be written for the first time

A copy of this page is made onto an unused page.

The current page table is then made to point to the copy

The update is performed on the copy

- 33.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

Shadow Paging (Cont.)

To commit a transaction :

1. Flush all modified pages in main memory to disk

2. Output current page table to disk

3. Make the current page table the new shadow page table, as follows:

keep a pointer to the shadow page table at a fixed (known) location

on disk.

to make the current page table the new shadow page table, simply

update the pointer to point to current page table on disk

Once pointer to shadow page table has been written, transaction is

committed.

No recovery is needed after a crash — new transactions can start right

away, using the shadow page table.

Pages not pointed to from current/shadow page table should be freed

(garbage collected).

- 34.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

Shadow Paging

Directory

Current directory

Shadow directory

During the transaction execution, shadow directory is never

modified

Shadow page recovery

Free the modified database pages

Discard the current directory

Advantages

No-redo/no-undo

Disadvantages

Creating shadow directory may take a long time

Updated database pages change locations

Garbage collection is needed

- 35.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

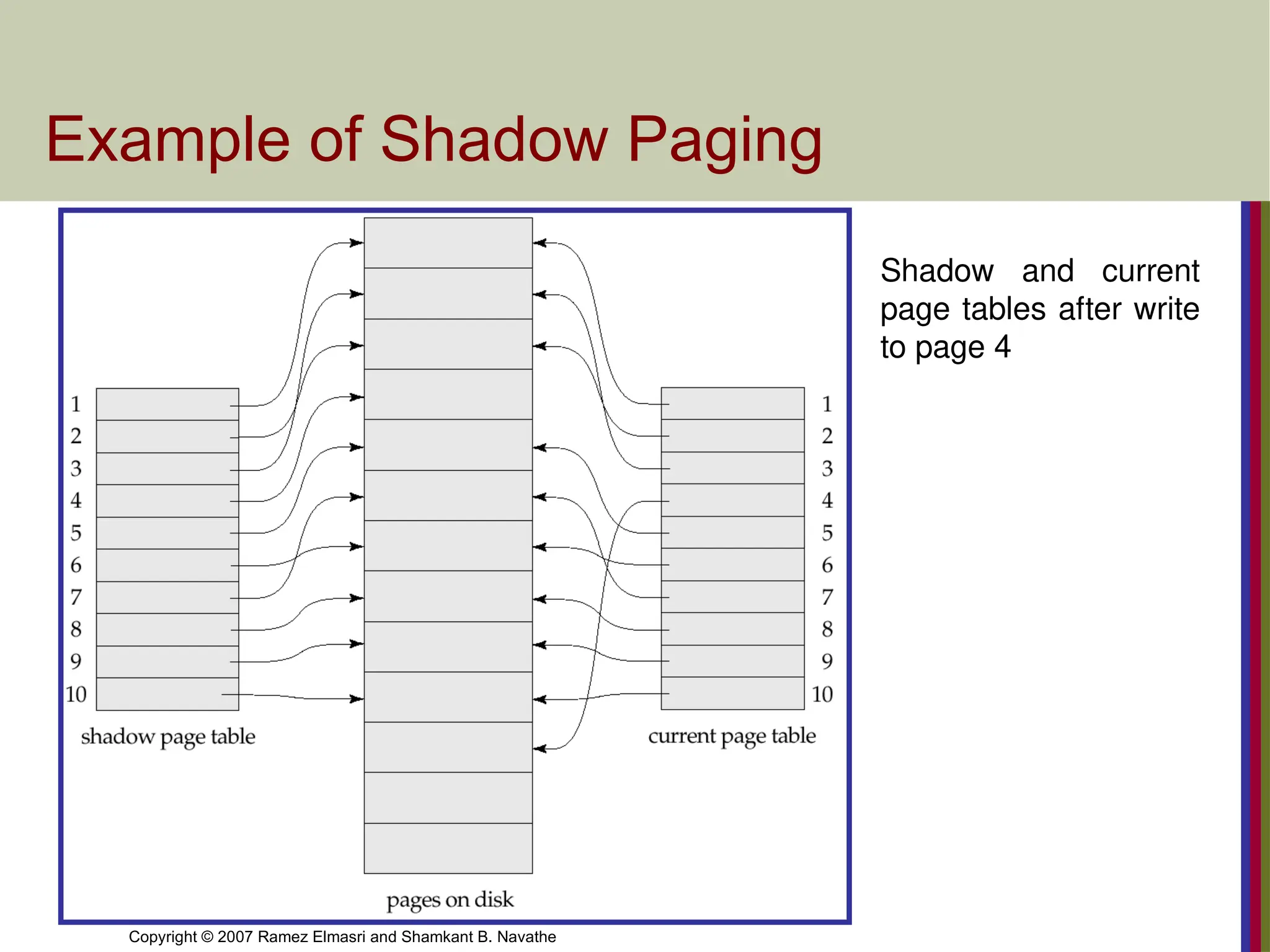

Example of Shadow Paging

Shadow and current

page tables after write

to page 4

- 36.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

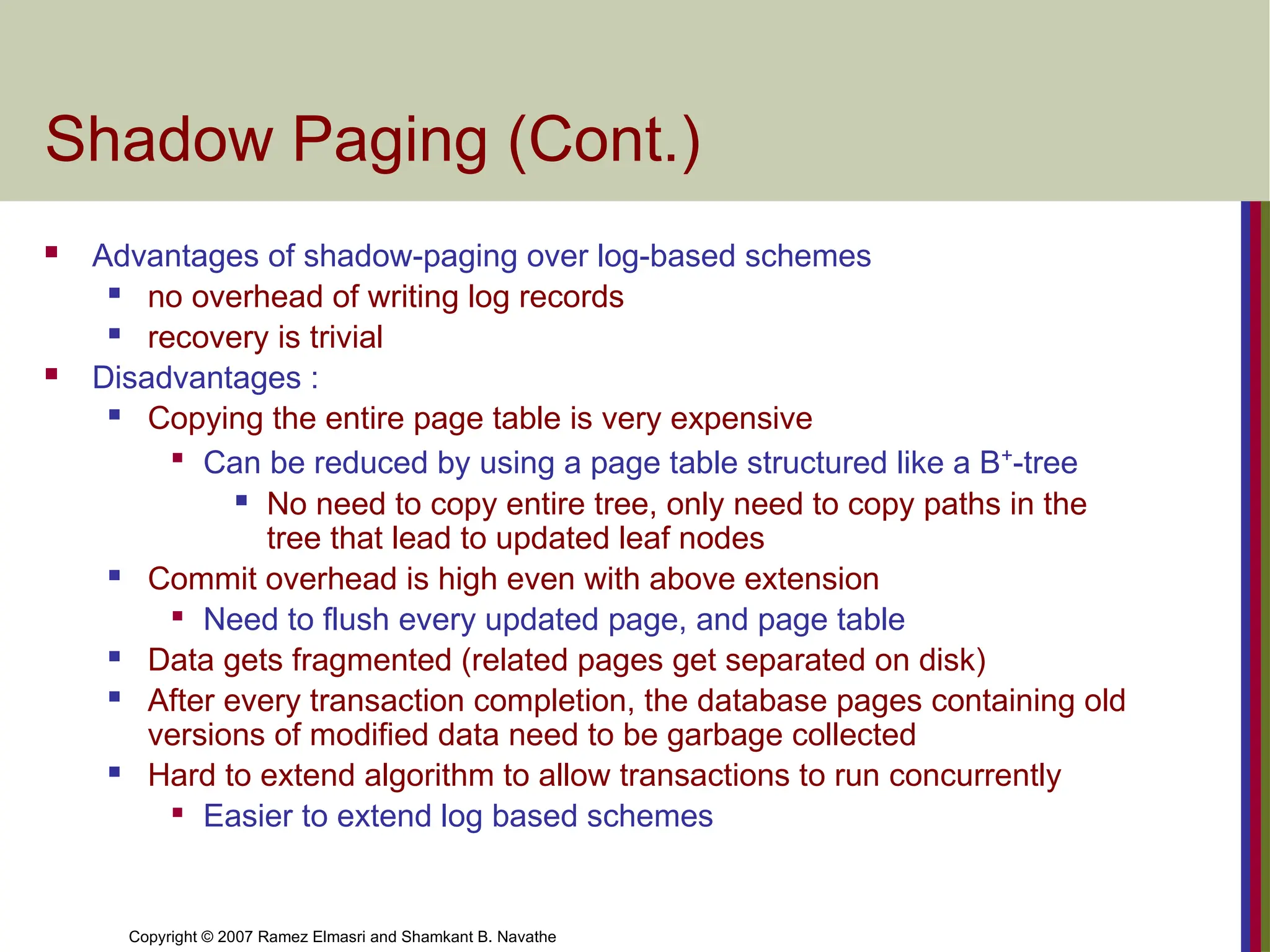

Shadow Paging (Cont.)

Advantages of shadow-paging over log-based schemes

no overhead of writing log records

recovery is trivial

Disadvantages :

Copying the entire page table is very expensive

Can be reduced by using a page table structured like a B+

-tree

No need to copy entire tree, only need to copy paths in the

tree that lead to updated leaf nodes

Commit overhead is high even with above extension

Need to flush every updated page, and page table

Data gets fragmented (related pages get separated on disk)

After every transaction completion, the database pages containing old

versions of modified data need to be garbage collected

Hard to extend algorithm to allow transactions to run concurrently

Easier to extend log based schemes

- 37.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

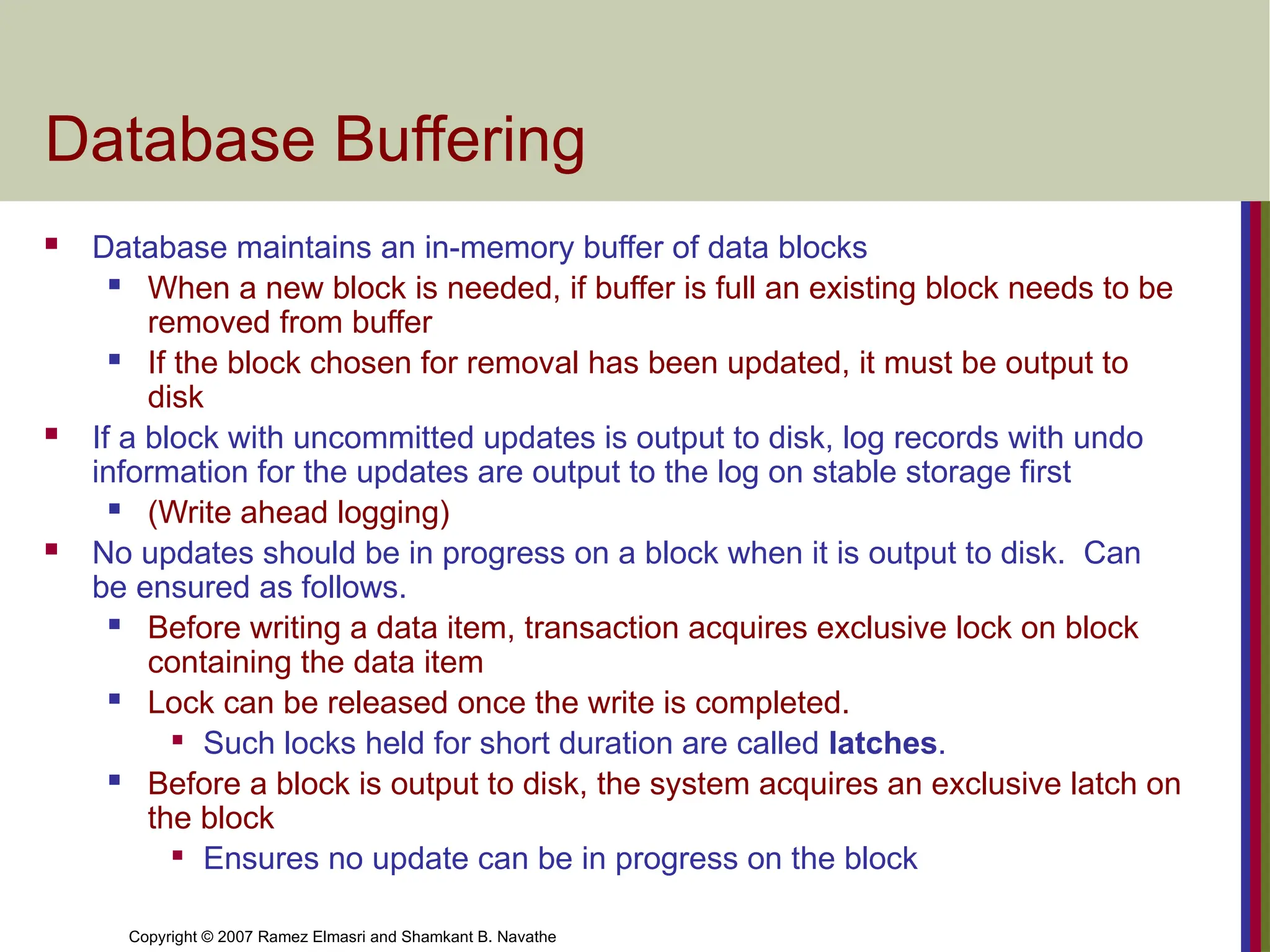

Database Buffering

Database maintains an in-memory buffer of data blocks

When a new block is needed, if buffer is full an existing block needs to be

removed from buffer

If the block chosen for removal has been updated, it must be output to

disk

If a block with uncommitted updates is output to disk, log records with undo

information for the updates are output to the log on stable storage first

(Write ahead logging)

No updates should be in progress on a block when it is output to disk. Can

be ensured as follows.

Before writing a data item, transaction acquires exclusive lock on block

containing the data item

Lock can be released once the write is completed.

Such locks held for short duration are called latches.

Before a block is output to disk, the system acquires an exclusive latch on

the block

Ensures no update can be in progress on the block

- 38.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

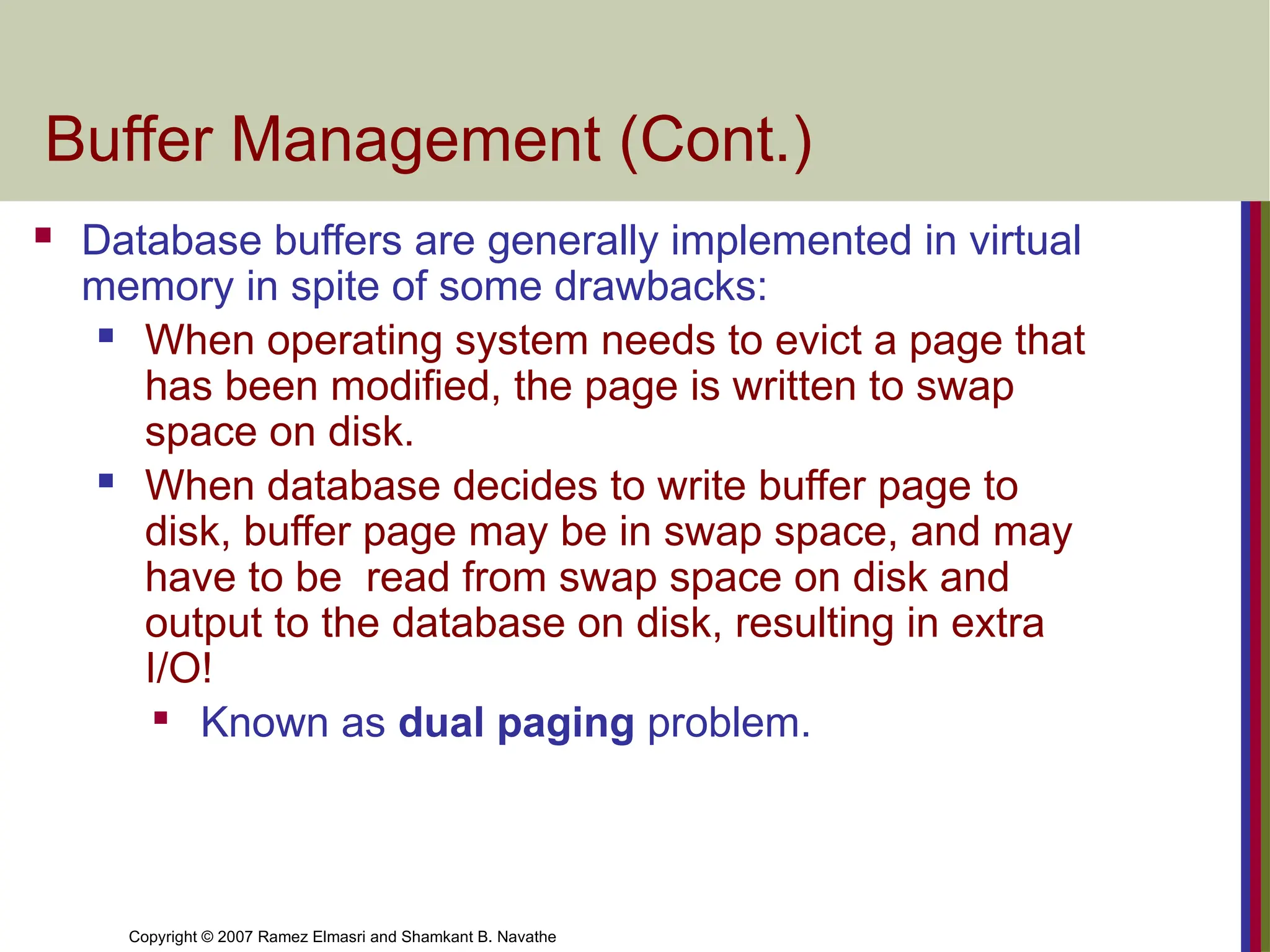

Buffer Management (Cont.)

Database buffers are generally implemented in virtual

memory in spite of some drawbacks:

When operating system needs to evict a page that

has been modified, the page is written to swap

space on disk.

When database decides to write buffer page to

disk, buffer page may be in swap space, and may

have to be read from swap space on disk and

output to the database on disk, resulting in extra

I/O!

Known as dual paging problem.

- 39.

- 40.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe

Next Slides are not in Syllabus

Slide 19- 49

- 41.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 50

Database Recovery

The ARIES Recovery Algorithm

The ARIES Recovery Algorithm is based on:

WAL (Write Ahead Logging)

Repeating history during redo:

ARIES will retrace all actions of the database

system prior to the crash to reconstruct the

database state when the crash occurred.

Logging changes during undo:

It will prevent ARIES from repeating the completed

undo operations if a failure occurs during recovery,

which causes a restart of the recovery process.

- 42.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 51

Database Recovery

The ARIES Recovery Algorithm (contd.)

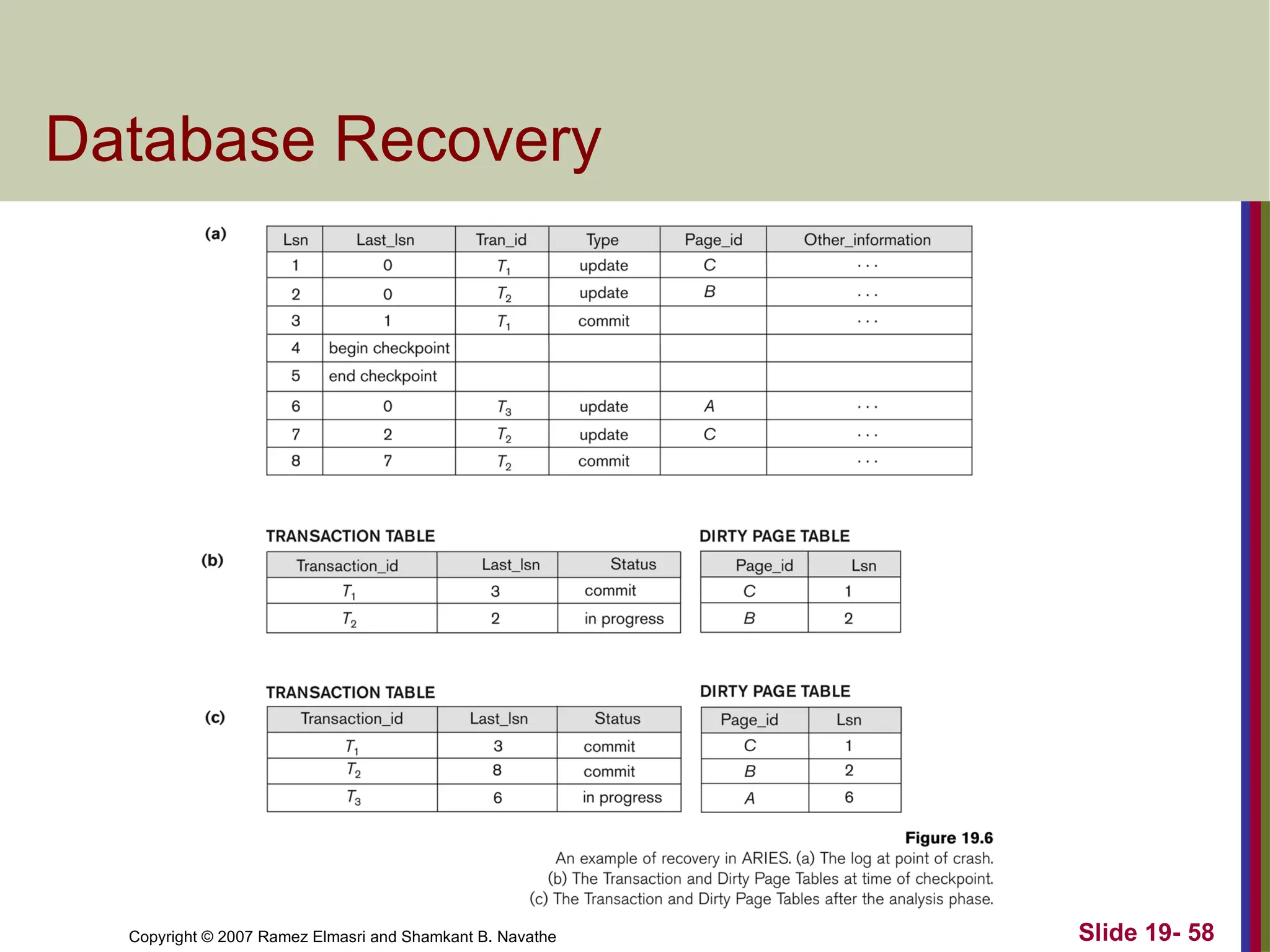

The ARIES recovery algorithm consists of three steps:

1. Analysis: step identifies the dirty (updated) pages in the

buffer and the set of transactions active at the time of

crash. The appropriate point in the log where redo is to

start is also determined.

2. Redo: necessary redo operations are applied.

3. Undo: log is scanned backwards and the operations of

transactions active at the time of crash are undone in

reverse order.

- 43.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 52

Database Recovery

The ARIES Recovery Algorithm (contd.)

The Log and Log Sequence Number (LSN)

A log record is written for:

(a) data update

(b) transaction commit

(c) transaction abort

(d) undo

(e) transaction end

In the case of undo a compensating log record is

written.

- 44.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 53

Database Recovery

The ARIES Recovery Algorithm (contd.)

The Log and Log Sequence Number (LSN) (contd.)

A unique LSN is associated with every log record.

LSN increases monotonically and indicates the disk address

of the log record it is associated with.

In addition, each data page stores the LSN of the latest log

record corresponding to a change for that page.

A log record stores

(a) the previous LSN of that transaction

(b) the transaction ID

(c) the type of log record.

- 45.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 54

Database Recovery

The ARIES Recovery Algorithm (contd.)

The Log and Log Sequence Number (LSN) (contd.)

A log record stores:

1. Previous LSN of that transaction: It links the log record of each

transaction. It is like a back pointer points to the previous record

of the same transaction

2. Transaction ID

3. Type of log record

For a write operation the following additional information is logged:

1. Page ID for the page that includes the item

2. Length of the updated item

3. Its offset from the beginning of the page

4. BFIM of the item

5. AFIM of the item

- 46.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 55

Database Recovery

The ARIES Recovery Algorithm (contd.)

The Transaction table and the Dirty Page table

For efficient recovery following tables are also

stored in the log during checkpointing:

Transaction table: Contains an entry for each

active transaction, with information such as

transaction ID, transaction status and the LSN of

the most recent log record for the transaction.

Dirty Page table: Contains an entry for each dirty

page in the buffer, which includes the page ID and

the LSN corresponding to the earliest update to that

page.

- 47.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 56

Database Recovery

The ARIES Recovery Algorithm (contd.)

Checkpointing

A checkpointing does the following:

Writes a begin_checkpoint record in the log

Writes an end_checkpoint record in the log. With this record

the contents of transaction table and dirty page table are

appended to the end of the log.

Writes the LSN of the begin_checkpoint record to a special

file. This special file is accessed during recovery to locate the

last checkpoint information.

To reduce the cost of checkpointing and allow the system to

continue to execute transactions, ARIES uses “fuzzy

checkpointing”.

- 48.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 57

Database Recovery

The ARIES Recovery Algorithm (contd.)

The following steps are performed for recovery

Analysis phase: Start at the begin_checkpoint record and

proceed to the end_checkpoint record. Access transaction table

and dirty page table are appended to the end of the log. Note that

during this phase some other log records may be written to the log

and transaction table may be modified. The analysis phase

compiles the set of redo and undo to be performed and ends.

Redo phase: Starts from the point in the log up to where all dirty

pages have been flushed, and move forward to the end of the log.

Any change that appears in the dirty page table is redone.

Undo phase: Starts from the end of the log and proceeds

backward while performing appropriate undo. For each undo it

writes a compensating record in the log.

The recovery completes at the end of undo phase.

- 49.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 58

Database Recovery

- 50.

Copyright © 2007Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 60

Summary

Databases Recovery

Types of Failure

Transaction Log

Data Updates

Data Caching

Transaction Roll-back (Undo) and Roll-Forward

Checkpointing

Recovery schemes

ARIES Recovery Scheme

Recovery in Multidatabase System

![Copyright © 2007 Ramez Elmasri and Shamkant B. Navathe Slide 19- 23

Database Recovery

7 Checkpointing

Time to time (randomly or under some criteria) the

database flushes its buffer to database disk to minimize

the task of recovery. The following steps defines a

checkpoint operation:

1. Suspend execution of transactions temporarily.

2. Force write modified buffer data to disk.

3. Write a [checkpoint] record to the log, save the log to disk.

4. Resume normal transaction execution.

During recovery redo or undo is required to transactions

appearing after [checkpoint] record.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/lecture11-backupandrecovery-drpreetiaggarwal-250316162900-77552f48/75/LECTURE-11-Backup-and-Recovery-Dr-Preeti-Aggarwal-pptx-23-2048.jpg)