This document provides an overview and history of databases and the SQL language. It discusses early non-relational database systems that stored data hierarchically or as networks, and introduces Dr. E.F. Codd who in 1970 proposed representing data as sets of tables, known as the relational model. The remainder of the document outlines the structure and contents of the book "Learning SQL" which teaches the SQL language for querying and manipulating data in relational database systems.

![the MySQL implementation of regular expressions:

mysql> SELECT emp_id, fname, lname

-> FROM employee

-> WHERE lname REGEXP '^[FG]';

+--------+-------+----------+

| emp_id | fname | lname |

+--------+-------+----------+

| 5 | John | Gooding |

| 6 | Helen | Fleming |

| 9 | Jane | Grossman |

| 17 | Beth | Fowler |

+--------+-------+----------+

4 rows in set (0.00 sec)

The regexp operator takes a regular expression ('^[FG]'

in this example) and applies it to the expression on the

lefthand side of the condition (the column lname). The

query now contains a single condition using a regular

expression rather than two conditions using wildcard

characters.

Oracle Database and Microsoft SQL Server also support

regular expressions. With Oracle Database, you would

use the regexp_like function instead of the regexp

operator shown in the previous example, whereas SQL

Server allows regular expressions to be used with the

like operator.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/learningsqlbyalanbeaulieu-231102075622-ef996832/85/_Learning-SQL_-by-Alan-Beaulieu-pdf-115-320.jpg)

![Working with Temporal Data

Of the three types of data discussed in this chapter

(character, numeric, and temporal), temporal data is the

most involved when it comes to data generation and

manipulation. Some of the complexity of temporal data is

caused by the myriad ways in which a single date and

time can be described. For example, the date on which I

wrote this paragraph can be described in all the

following ways:

Wednesday, September 17, 2008

9/17/2008 2:14:56 P.M. EST

9/17/2008 19:14:56 GMT

2612008 (Julian format)

Star date [−4] 85712.03 14:14:56 (Star Trek format)

While some of these differences are purely a matter of

formatting, most of the complexity has to do with your

frame of reference, which we explore in the next section.

Dealing with Time Zones

Because people around the world prefer that noon

coincides roughly with the sun’s peak at their location,

there has never been a serious attempt to coerce

everyone to use a universal clock. Instead, the world has

been sliced into 24 imaginary sections, called time zones;

within a particular time zone, everyone agrees on the

current time, whereas people in different time zones do

not. While this seems simple enough, some geographic

regions shift their time by one hour twice a year

(implementing what is known as daylight saving time)

and some do not, so the time difference between two

points on Earth might be four hours for one half of the

year and five hours for the other half of the year. Even

within a single time zone, different regions may or may

not adhere to daylight saving time, causing different

clocks in the same time zone to agree for one half of the

year but be one hour different for the rest of the year.

While the computer age has exacerbated the issue,

people have been dealing with time zone differences

since the early days of naval exploration. To ensure a](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/learningsqlbyalanbeaulieu-231102075622-ef996832/85/_Learning-SQL_-by-Alan-Beaulieu-pdf-187-320.jpg)

![The Case Expression

All of the major database servers include built-in

functions designed to mimic the if-then-else statement

found in most programming languages (examples include

Oracle’s decode() function, MySQL’s if() function, and

SQL Server’s coalesce() function). Case expressions are

also designed to facilitate if-then-else logic but enjoy two

advantages over built-in functions:

The case expression is part of the SQL standard

(SQL92 release) and has been implemented by

Oracle Database, SQL Server, MySQL, Sybase,

PostgreSQL, IBM UDB, and others.

Case expressions are built into the SQL grammar and

can be included in select, insert, update, and

delete statements.

The next two subsections introduce the two different

types of case expressions, and then I show you some

examples of case expressions in action.

Searched Case Expressions

The case expression demonstrated earlier in the chapter

is an example of a searched case expression, which has

the following syntax:

CASE

WHEN C1 THEN E1

WHEN C2 THEN E2

...

WHEN CN THEN EN

[ELSE ED]

END

In the previous definition, the symbols C1, C2,..., CN

represent conditions, and the symbols E1, E2,..., EN

represent expressions to be returned by the case

expression. If the condition in a when clause evaluates to

true, then the case expression returns the corresponding

expression. Additionally, the ED symbol represents the

default expression, which the case expression returns if

none of the conditions C1, C2,..., CN evaluate to true (the

else clause is optional, which is why it is enclosed in

square brackets). All the expressions returned by the](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/learningsqlbyalanbeaulieu-231102075622-ef996832/85/_Learning-SQL_-by-Alan-Beaulieu-pdf-286-320.jpg)

![+---------+-------------+------------------------+

| cust_id | fed_id | name |

+---------+-------------+------------------------+

| 1 | 111-11-1111 | James Hadley |

| 2 | 222-22-2222 | Susan Tingley |

| 3 | 333-33-3333 | Frank Tucker |

| 4 | 444-44-4444 | John Hayward |

| 5 | 555-55-5555 | Charles Frasier |

| 6 | 666-66-6666 | John Spencer |

| 7 | 777-77-7777 | Margaret Young |

| 8 | 888-88-8888 | Louis Blake |

| 9 | 999-99-9999 | Richard Farley |

| 10 | 04-1111111 | Chilton Engineering |

| 11 | 04-2222222 | Northeast Cooling Inc. |

| 12 | 04-3333333 | Superior Auto Body |

| 13 | 04-4444444 | AAA Insurance Inc. |

+---------+-------------+------------------------+

13 rows in set (0.01 sec)

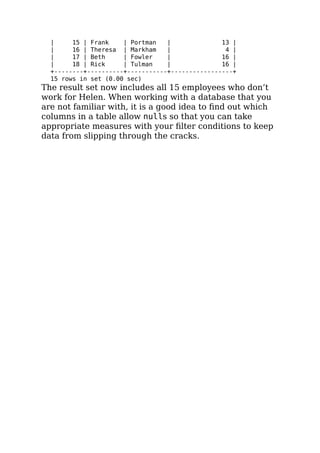

This version of the query includes only the customer

table in the from clause and uses correlated subqueries

to retrieve the appropriate name for each customer. I

prefer this version over the outer join version from

earlier in the chapter, since the server reads from the

individual and business tables only as needed instead

of always joining all three tables.

Simple Case Expressions

The simple case expression is quite similar to the

searched case expression but is a bit less flexible. Here’s

the syntax:

CASE V0

WHEN V1 THEN E1

WHEN V2 THEN E2

...

WHEN VN THEN EN

[ELSE ED]

END

In the preceding definition, V0 represents a value, and

the symbols V1, V2,..., VN represent values that are to be

compared to V0. The symbols E1, E2,..., EN represent

expressions to be returned by the case expression, and

ED represents the expression to be returned if none of

the values in the set V1, V2,..., VN match the V0 value.

Here’s an example of a simple case expression:

CASE customer.cust_type_cd

WHEN 'I' THEN](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/learningsqlbyalanbeaulieu-231102075622-ef996832/85/_Learning-SQL_-by-Alan-Beaulieu-pdf-288-320.jpg)