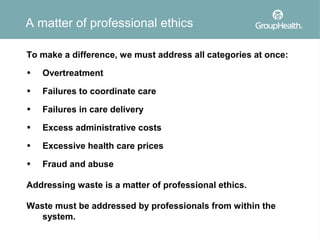

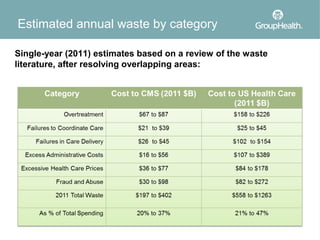

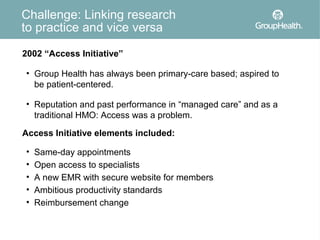

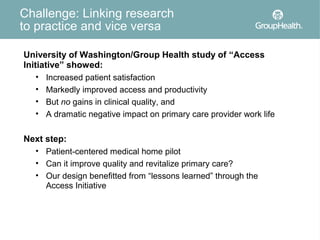

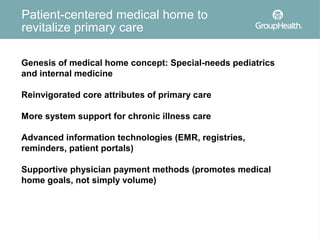

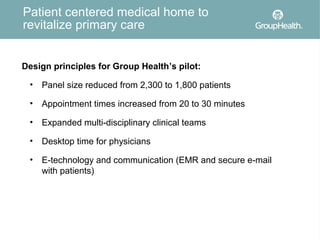

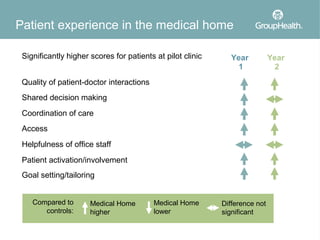

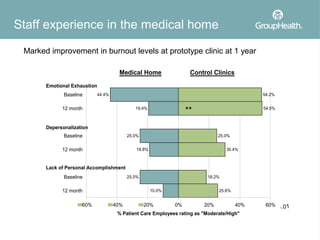

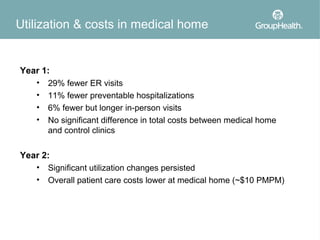

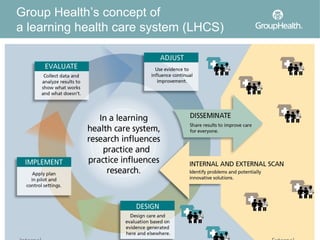

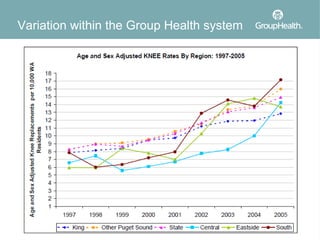

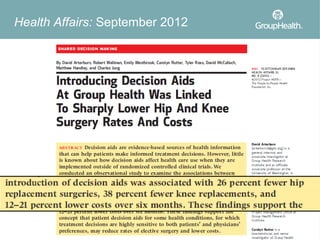

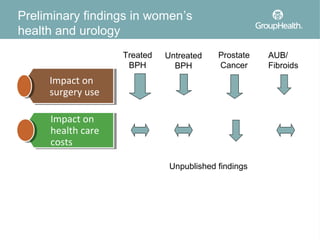

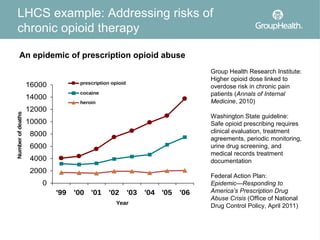

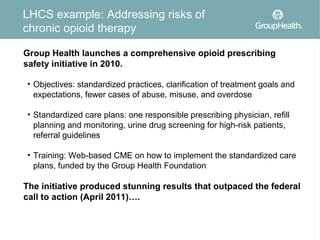

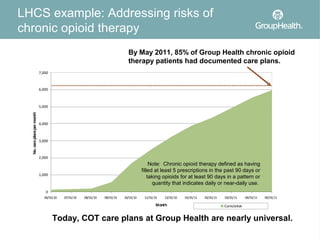

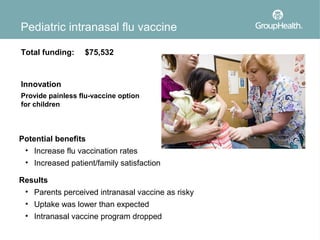

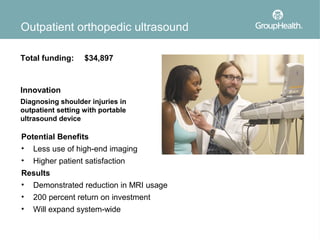

The document discusses the concept of learning health care systems (LHCS) as a potential solution to the ongoing challenges in the U.S. health care system, including issues of quality, access, and cost. It highlights the Group Health Cooperative as a successful model of LHCS that integrates research and clinical practice, demonstrating improvements in patient care and cost efficiency. The document also outlines various initiatives and research efforts aimed at reducing waste and enhancing patient-centered care within the healthcare framework.