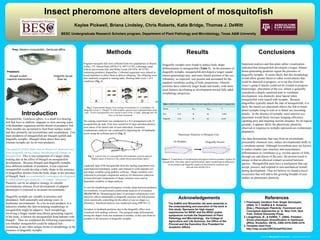

Mosquitofish were raised in environments with and without dragonfly nymphs to observe phenotypic plasticity. Statistical analysis found mosquitofish developed a longer, thinner posterior region and more lateral eye placement in the presence of dragonfly nymphs. These traits likely aid in detecting and evading attacks. The study demonstrates non-contact chemical cues can induce vertebrate developmental shifts, representing a novel example of phenotypic plasticity in response to invertebrate predators.