The document discusses the intertwining relationship between vision, embodiment, and the cultural constructions of subjectivity, particularly in the context of photography and mental illness. It examines historical practices from the 19th century, illustrating how photographic technologies shaped perceptions of mental health and identity, revealing a complex relationship between authenticity and performance. The analysis highlights contemporary video art as a continuation of this discourse, where artists explore the fragility of the self through performative acts recorded for the camera.

![104 111,11111,1 lowry

i.:aling it, the position of the observer is displaced from any direct engagemen

wilh the participants in the scene. Toe spectator is, through this deflectim

positioned so that he or she cannot identify with the subject, but must instea

observe them. In each case he or she is confronted with the spectacle of

clinical theatre and is thereby situated in a place from which the subject

behaviour demands not to be engaged with or responded to, but instead to b

V •. 1ead as a set of sympt�signs of sorne invisible and unarticulated traumt,

Both these works use the quasi-clinical heritage of photographic technologie

to define the individual subject as inherently unstable and hysterical, and tof,

establish the screen of video projection as a site for the display and perforJ

manee of their symptoms. Toe medium of video projection has thus become,

in a very material way, associated with a particular way of understanding what

it is to be a person in contemporary society.

However, developments in the way in which video portraits have been

installed in recent years have given their relationship with the spectator an

'::/::.. added complexity. Toe size and scale of these projectionsand their architectural

.¡.__ presence situate them in a very different domain from that of work displayed

on a monitor. And the emphasis on a confrontation with the face itself means

that the spectator's relationship to the subject is of a very different kind from

that represented by the two works described above. In both cases the spectator

could be a detached observer of hysterical behaviour, whereas in these works

the subject is larger than life andin a sense confronts thespectator, requiring of

them, in sorne obscure and indefinable way, that they read their signs. Between

,()'

' �

C:_ -

)

r-. l

•;,J)

·"-

�'

..e

'·

1996 and 2003 Thomas Struth recorded a series of large-scale video portraits

<½,_ __Q!at were to be ro·ected onto hanging screens. These wefe displayed li¡;

/J' spectral_p

resences around t e uge museum space, the apparatus of projec-

tfon subtl�was an archival structure underpinning the work,

arguably borrowed from the example of still photographer August Sander's

early twentieth-century portraits of subjects classified by profession: Struth's

subjects included a number of distinct bourgeois social types, including an

architect, a student, an art dealer, Struth's godson, a little girl ... Toe subjects

were not selected for their individuality but because, at sorne level, they were

fairly unremarkable, resolutely middle-class, benignly typical - their personal

histories were unimportant for the work. It was their anonymity and conse

quently their emptiness as potential spaces for the inscription of meaning and

the projection of fantasy that made them compelling. This anonymity initially

impelled the spectator to consider these portraits at the level of surface, as

occupying the flat dimensions of the screen. Without a sense of a particular

person to whom one might begin to ascribe sorne meaning and identity, the

faces that were presented to the spectator could only return his or her reading

back onto themselves. Their blankness refused any narrative coding of the

time of the oose. Toe emohasis on snectacularlv 1::mrp_ fnrm;il. ;incl �imnlP

Projecting syrnpl.0111',

screens also encouraged the spectator to see the screens as modernist objects,

drawing attention to the elusive materiality of the surface of the screen itselC

reiriforcing the fact that, though it offered a representational depth, the screen

was also an object that was absolutely without depth, absolutely thin: one

could walk behind it.

These screens, though, also operated as sites for exposing the self under

a certain duress. Toe subjects sat or stood for a whole hour in front of the

camera, as still as possible, their concentration occasionally interrupted by the

blinkof an eye, a slight wriggle of the body or shifting of their pose.Under the

imposition of the rigid terms of engagement they entered into a trance-like

state, alternating almost imperceptibly between a subtle self-consciousness in

front of the camera and a withdrawn meditative state, flickering in between

the place of being and the requirement to become a sign. At times it seemed

that these people were on the brink of becoming so self-absorbed that they

might slip out of visibility itself, withdraw into sorne other imaginary space

and leave one with only the surface of the screen to gaze at. Toe relation

ship between the surface materiality of the image and the performance was

absolutely fragile and thin. But in that context the subject seems fragile too,

holding him- or herself together for the sake of the recording. In this sense,

despite the calmer tone of these works, which contrasts with those earlier

video pieces I have discussed, Struth's works could, perhaps surprisingly, be

seen to reinforce the sense of the screen as a site for the inscription of our

psychic fragility.

-One way offñterpreting these portraits is as being about the way in which

��ituted as subjects in a technological culture; they dramatise the

tension between technologies of surveillance and the sélf-determination of

-performance that is at the heart of my discussion here. But the works also

rarse rmportant questions about the gaze and the significance it takes on in the

gallery context. Struth's screens were suspended from the ceiling and hung,

angled away from each other so that they could only be looked at one at a

time.Holding their pose as still as possible for such a long period of time and

staring straight into the camera lens was certainly an exercise in endurance for

the subjects, one which had its own power dynamic in relation to the mobile,

shiftingaudience that passed through the museumhalls where it was installed.

Toe spectator felt compelled to return the gaze, to watch back, but inevitably

could not meet the challenge - was out-faced, and turned to move on to the

next encounter uncomfortably aware of his or her irrelevance to the subject

they had left behind. Part of the discomfiture was of course related to the fact

that the gaze that seemed to be directed at the spectator was not directed at

him or her at all, but at the camera. Toe very directness of the apparent form

of address was in fact an illusion, masking the presence of the filmic apparatus.

'Tl, ,o r"l'l'Y,::H"'., ; ,..., ¾-l-.� r- T�-rr,....,],- ...,,,..,....-,..,,,....,..,._+,...,. ;l ,..., 1-l!- ...l �-�J..!_ .&.L - __! --- _ 1 .C. - 1 _] y_. - •,

105

�](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/joannalowry-proyectandosintomas-ingles-241213150606-4a6dde1c/85/Joanna-Lowry-Proyectando-Sintomas-Ingles-pdf-7-320.jpg)

!['"º /1 1,11111,1 l 1 1fVIV

1iil' s¡wcialor's gaze, but it was now absent and became a kind of vanishing

¡1oi111 for a returning gaze that could never be met.

Whcn faced with works like this, we also feel as though there is a sense

in which, in front of the image, it is we who are positioned in the place of

!he visible. We are reminded of Lacan's discomfiture in his anecdote about

thc sardine can bobbing in the sea, glinting in the sun, not seeing him as he

sits in the boat with the laughing fishermen, but nevertheless placing him

in the field of the visible.1

1

Now we become aware that the very fact that the

subjects of these works don't see us exposes the space of the visible as far

from being a continuous plane. It is in fact uneven, fissured, and folded, and

we are reminded that this space of visibility is peculiarly complicated by the

intervention of the apparatus. It is this fault-line in the visible, at thej>9Jnt of

the illusory_C()l1Vergence ()f th;s_e t;;.�Jia�-es=-thejuqfrc:fi:afld_tl-i�_ §pi_�tator's

- that defines the difference and the distánce between us.

Struth's work can be seen as typical of a genre of contemporary video

portraiturecentred on thelargeprojectedface.I havesuggestedthatthere is an

ambivalence within this work about how it addresses the spectator, not oE!Y,

as the diseng3:ged spe_ct_atQr ofªIU-º.d�rn_i�t_tr_a_cfü_i9I12.p _

t1J aJ_s9_i!_s__�_I1..Qtject of

_the gáze produced by the image, and finally and perhaps most fundamentally

as a spectator who is 'diagnostic' and who can see and interpret the vulner

ability of the subject portrayed. This is a hypothesised spectator who can

clearly be traced back to the traditions of photographic representation that

were discussed earlier in this essay. However, in many contemporary video

installations we are no longer positioned asobjective observers by our specta

torial position; we are positioned instead as embodied spectators in the space;

the theatre includes us; it is fundamentally dialogic. In such works there is a

convergence between a diagnostic gaze and a space of performance of the self

within a dialogical framework.This establishes the space of projection as one

that is bounded by the psychical parameters of the therapeutic relationship.

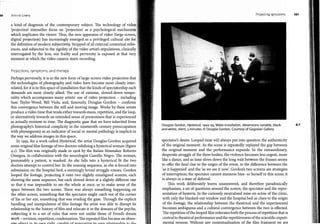

In 2006 Phil Collins installed a major piece of work, gerr;egin geri donü�ü

(the return ofthe real) (2005), in the Tate Gallery Turner Prize show (figure

4-4). In a long darkened room, empty apart from benches for the spectators

clown each side, two projections faced each other. On one wall, at a large

scale, there was a series of faces of Turkish individuals who had been partici

pants in reality TV shows, each recounting in a series of lengthy interviews

the impact that this experience had had upon their life.On the opposite wall

a separate projection displayed their interviewer. He was himself a director

of rcality shows, but in this situation took the role of a kindly counsellor or

lhcrapist, eliciting their story, encouraging them to tell more, nodding his

asscnl lo their attempts to construct the narrative of their lives, sympatheti

c,dly c11gaging with their confusion and despair, and, by his very neutral and

11011 j11d¡_,_c111<:11tal nrcsen,f'_ pnrn11r"aina thPm t� �� ,,._+1-,~- ---l ·-11 -

Projl'l lÍIIIJ •,y11r¡>l<>III',

Phil Collins, ger�egin geri donü�ü (the return ofthe real), 2005. Multi-channel video

installation, colour, sound, 60 minutes. lnstallation view, Ausstellungshalle zeitgeni::is

sische Kunst Münster, 2007. Photo: Thomas Wrede. Courtesy Shady Lane Productions.

Whilst the former participants were represented against a blank backdrop

- representing the neutrality of the 'studio' as a site of representation - the

director was clearly seen in the studio that is the site of production, with all his

equipment behind him, theinterviewees' facesbeingsimultaneouslyscreened,

as they spoke, on a monitor behind him. This screen, the one displaying the

director, therefore represented not only the scene of production but also that

of projection, and in this sense it also implicitly complied with the construc

tion of the kind of narcissistic structuring of video space that was endemic to

the forms of early video art referred to above. In such works artists performed

to the camera whilst simultaneously being seen performing on the monitor, a

form of practice which Rosalind Krauss has famously declared to be charac

teristic of the medium itself: 'The body ... [is] centred between two machines

that are the opening and closing of a parenthesis. The first of these is the

camera; the second is the monitor, which re-projects the performer's image

with the immediacy of a mirror:12

The interviews, then, in the way in which they were displayed, theatri-

107

4.4

'

ij'

,,

1¡

1

1

:,1

lji

'1

'1

'l.

[!

j]il

,1,

¡Ji

:''¡:

1

!](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/joannalowry-proyectandosintomas-ingles-241213150606-4a6dde1c/85/Joanna-Lowry-Proyectando-Sintomas-Ingles-pdf-8-320.jpg)