The document summarizes a study that analyzed 4 genetically engineered strains of Clostridium thermocellum with differing pathways for converting phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to pyruvate. The strains were cultured and their metabolite concentrations and reversibility of reactions were measured to calculate free energy changes. Strain 1138 diverted flux through the malate shunt, strain 1163 expressed an exogenous pyruvate kinase, and strain 1251 expressed pyruvate kinase and deleted PPDK and the malate shunt. Strain 1163 had higher GDP and GTP, suggesting its PEP to oxaloacetate conversion was more efficient. Further optimizing the PEP to pyruvate pathway, such as

![Metabolomic and thermodynamic analysis of C. thermocellum strains

engineered for high ethanol production

Jordan Brown1, Dave Stevenson2, Daniel Amador-Noguez2

1-Department of Botany-Microbiology (Genetics), Ohio Wesleyan University

2-Department of Bacteriology, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Introduction

Ethanol is a carbon neutral fuel that can be produced from the microbial conversion of

cellulosic biomass [1]. One microorganism that is being engineered to perform this conversion

is the aerobic thermophillic bacteria, Clostridium thermocellum. Past efforts that focused solely

on metabolomic analyses have been able to increase ethanol production, but only up to a

certain amount. Studies show that the overall pathway of this conversion is not as energetically

favorable as in other biofuel producing strains. This causes the conversion of cellulose to

ethanol to proceed slowly and, in some cases, allows for reactions in the pathway to proceed in

reverse. By making the change in free energy (∆G) more negative at key steps in the reaction,

the overall reaction will become more spontaneous and proceed at a faster rate. This would

increase ethanol production, and drive down the price, allowing ethanol-based biofuels to

better compete with fossil fuels at the pump.

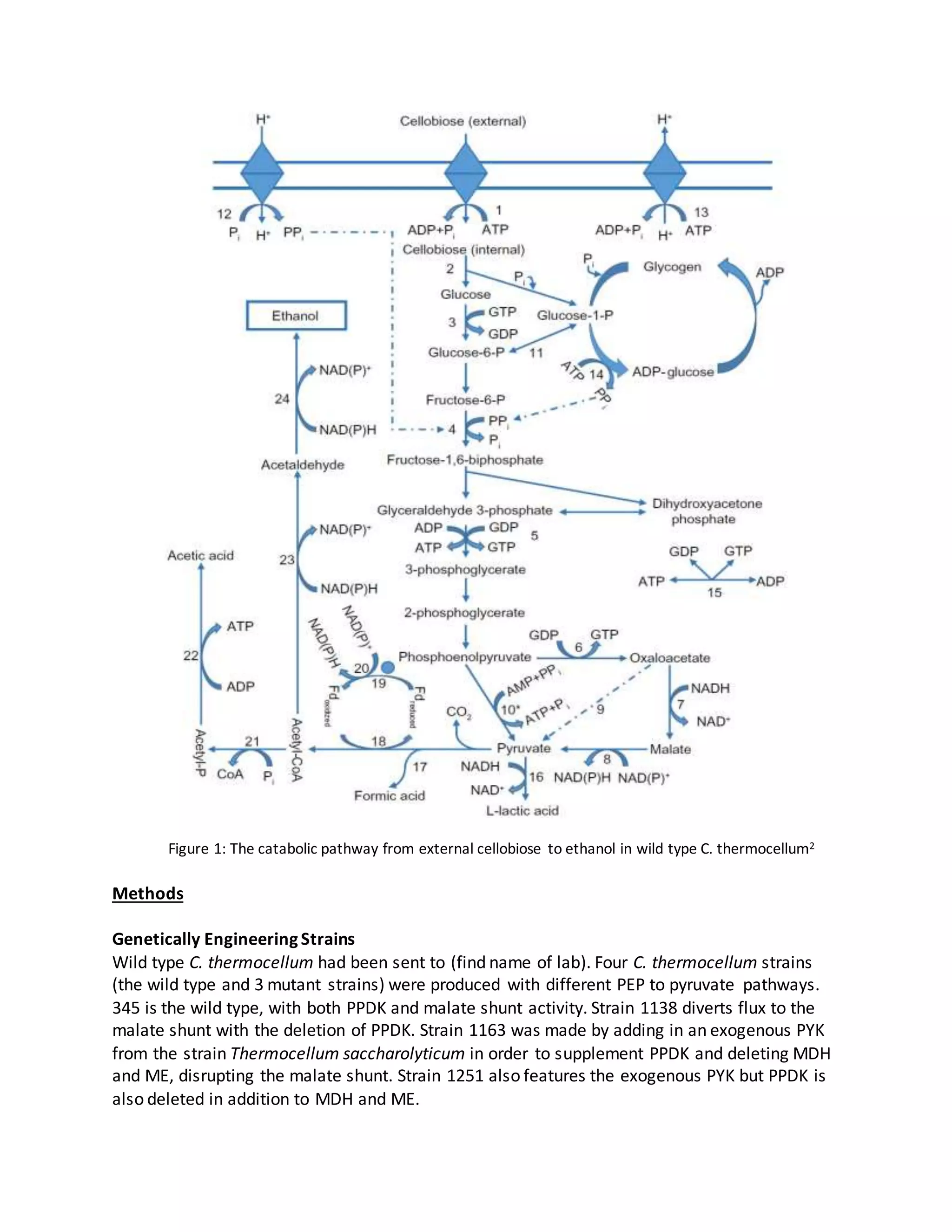

One key step in the pathway to be optimized is the conversion of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) to

pyruvate. C. thermocellum utilizes the Emben-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathway, but unlike

other bacteria that use this pathway it does not have the enzyme pyruvate kinase (PYK), which

catalyzes the direct conversion of PEP to pyruvate. Instead it utilizes two different pathways.

One is the direct conversion of PEP to pyruvate by a different enzyme, pyruvate phosphate

dikinase (PPDK). This pathway has been experimentally shown not to be able to be the sole

pathway in PEP to pyruvate conversion. The other pathway is the malate shunt, which uses PEP

carboxylase (PEPCK), malate dihydrogenase (MDH) and malic enzyme (ME)1. This pathway has

been shown to be able to be the sole PEP to pyruvate pathway.

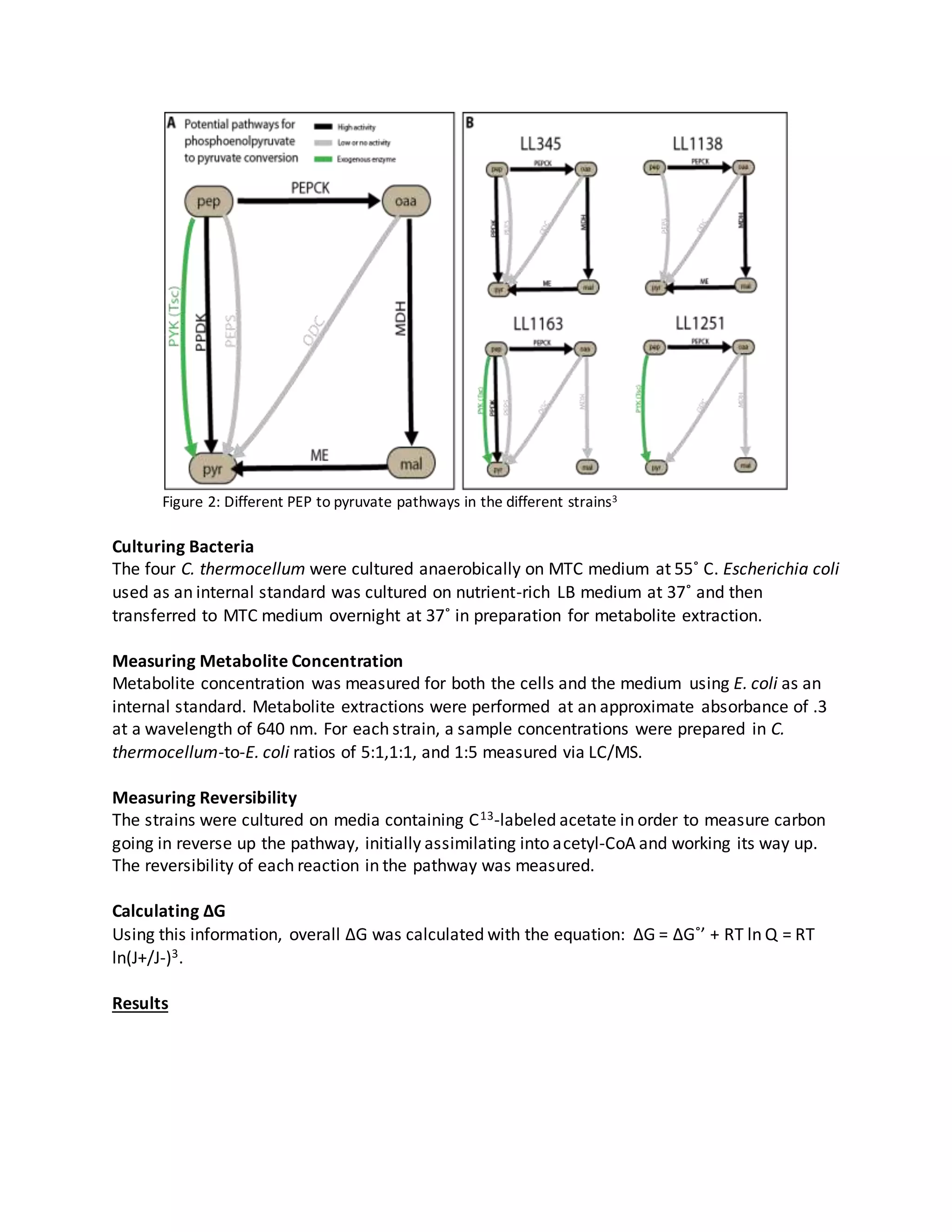

4 genetically engineered strains of C. thermocellum with differing pathways for the PEP to

pyruvate conversion were created and analyzed from an integrated metabolomic and

thermodynamic point of view. Comparison of alternate pathways for this conversion will allow

for determining the optimal PEP to pyruvate pathway to be used in C. thermocellum in

converting cellulosic biomass to ethanol.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18f65bde-10fc-4e37-8fb5-08825d007067-161025102119/75/JB-REU-Report-1-2048.jpg)

![Discussion

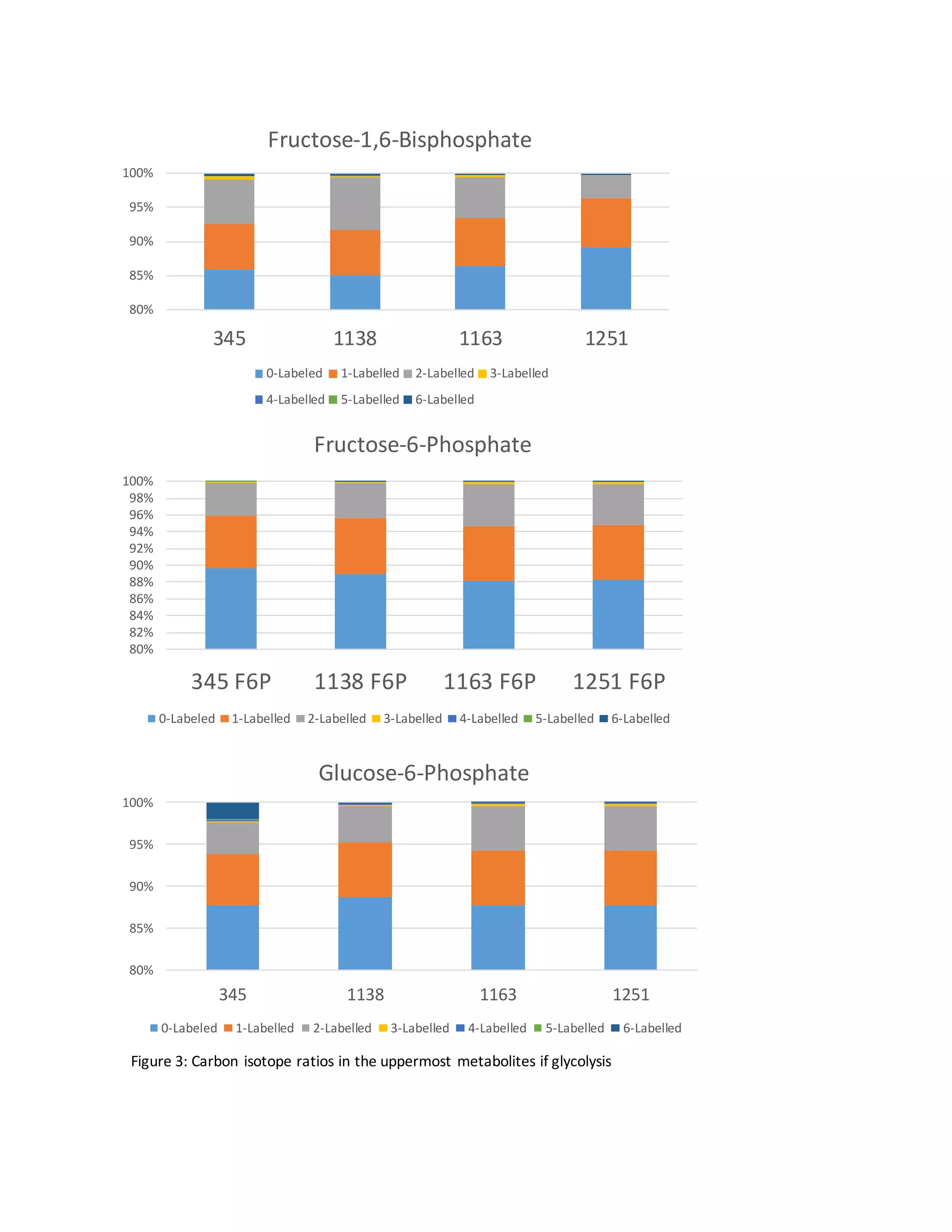

Glycolytic Reversibility

Contrary to most organisms, in which the reactions of upper glycolysis display essentially 100%

forward flux, the reactions in the EMP pathway of C. thermocellum display some extent of

reverse flux. This is particularly unique in the uppermost reactions of glycolysis[3].

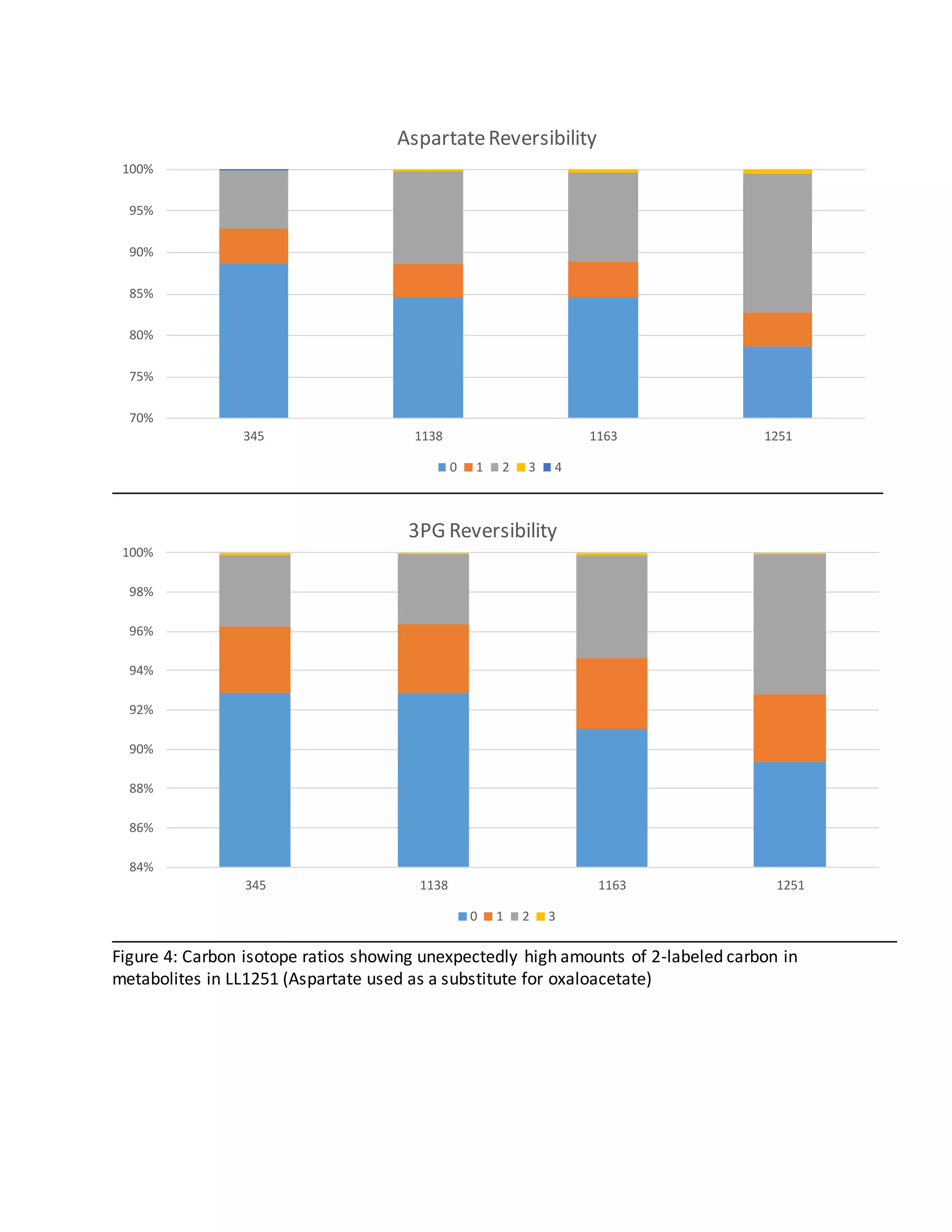

Secret Pathways

In LL1251 the only way for labeled carbon to make its way back through the pathway to

oxaloacetate is in reverse from pyruvate to PEP and then forward to oxaloacetate. Because the

enzyme responsible for PEP-> pyruvate (PYK) in LL1251 is relatively less reversible than those

used in other strains (PPDK or PYK and PPDK together), it would be expected for less label to be

found in oxaloacetate in LL1251. This however is not the case [4]. This suggests that there are

additional pathways present in this mutant involving these metabolites that have yet to be

elucidated.

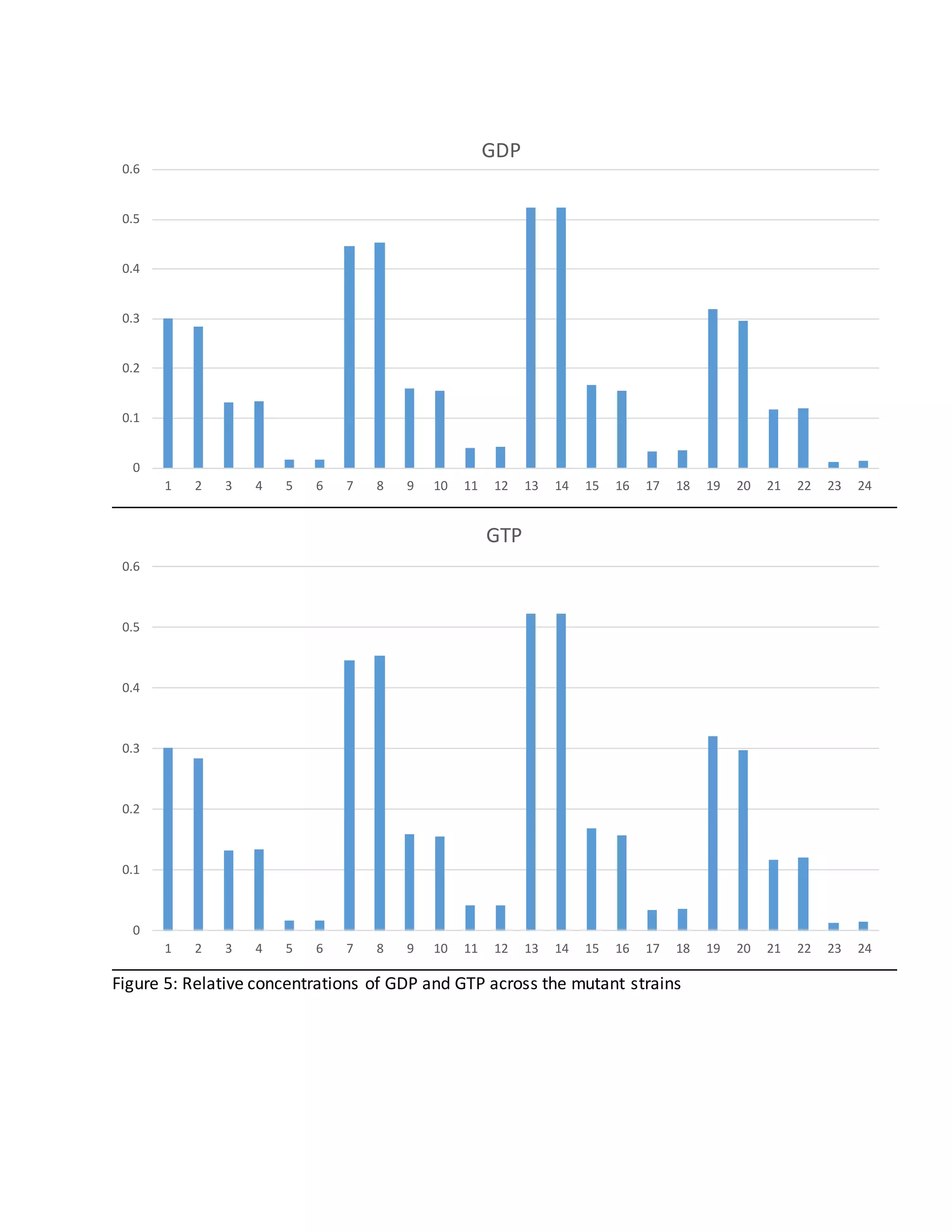

Increase GDP and GTP in LL1163

Compared to the other strains, there is a considerably higher relative concentration of GDP and

GTP in LL1163. This is particularly of interest because GTP production is linked to conversion of

PEP to oxaloacetate.

Further Research

C. thermocellum contains the gene for oxaloacetate decarboxylase (ODC), an enzyme that

catalyzes the conversion of oxaloacetate to pyruvate. However, there is no ODC expression in

wild type C.thermocellum. It would be of use to investigate this, and attempt to express this

gene to create a novel and potentially more efficient pathway for the PEP to pyruvate

conversion.

References

1) Olsen,Daniel G.,Manuel Hörl,TobiasFuhrer,JingxuanCui,MarybethI.Mahoney,Daniel Amador-

Noguez,LiangTian,Uwe Sauer,and Lee R. Lynd."Conversionof PhosphorenolpyruvatetoPyruvate in

ClostridiumThermocellum." *Currently underReview and NotYet Published (n.d.):n.pag.Print.

2) Chinn,Mari, andVeronicaMbaneme."ConsolidatedBioprocessingforBiofuel Production:Recent

Advances."EECTEnergy and Emission ControlTechnologies (2015): 23. Web.

3) Park, JunyoungO.,SaraA. Rubin,Yi-FanXu,Daniel Amador-Noguez,JingFan,TomerShlomi,and

JoshuaD. Rabinowitz."MetaboliteConcentrations,FluxesandFree EnergiesImplyEfficientEnzyme

Usage."NatureChemical Biology NatChemBiol (2016): n.pag. Print.

4) Flamholz,A.,E.Noor,A. Bar-Even,W.Liebermeister,andR.Milo."GlycolyticStrategyasa Tradeoff

between EnergyYieldandProteinCost." Proceedingsof theNationalAcademy of Sciences 110.24

(2013): 10039-0044. Print.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/18f65bde-10fc-4e37-8fb5-08825d007067-161025102119/75/JB-REU-Report-7-2048.jpg)