This document is a table of contents for a book on Java programming. It lists 19 chapters that introduce concepts related to computers, the Internet, Java, classes, objects, control statements, methods, arrays, inheritance and polymorphism. Each chapter is divided into multiple sections that cover specific topics in more detail. The table of contents provides an overview of the content and organization of the book.

![Section 23.3. Thread Priorities and Thread Scheduling...........................................................................................................1075

Section 23.4. Creating and Executing Threads.........................................................................................................................1077

Section 23.5. Thread Synchronization......................................................................................................................................1081

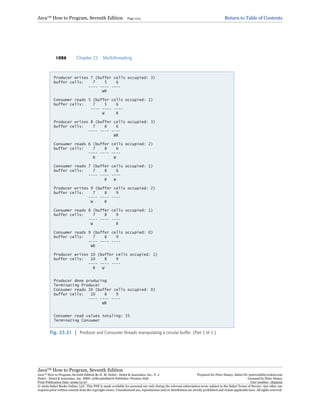

Section 23.6. Producer/Consumer Relationship without Synchronization............................................................................ 1090

Section 23.7. Producer/Consumer Relationship: ArrayBlockingQueue..................................................................................1097

Section 23.8. Producer/Consumer Relationship with Synchronization..................................................................................1100

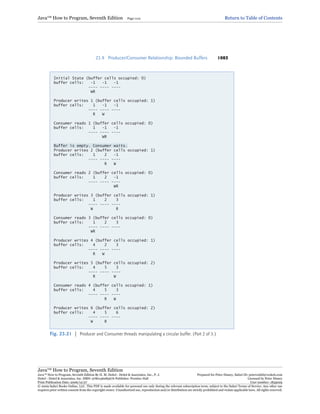

Section 23.9. Producer/Consumer Relationship: Bounded Buffers........................................................................................ 1106

Section 23.10. Producer/Consumer Relationship: The Lock and Condition Interfaces.......................................................... 1114

Section 23.11. Multithreading with GUI....................................................................................................................................1120

Section 23.12. Other Classes and Interfaces in java.util.concurrent........................................................................................ 1135

Section 23.13. Wrap-Up............................................................................................................................................................. 1135

Summary.................................................................................................................................................................................... 1136

Terminology............................................................................................................................................................................... 1142

Self-Review Exercises................................................................................................................................................................ 1143

Answers to Self-Review Exercises............................................................................................................................................. 1144

Exercises.................................................................................................................................................................................... 1144

Chapter 24. Networking......................................................................... 1146

Section 24.1. Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... 1147

Section 24.2. Manipulating URLs.............................................................................................................................................1148

Section 24.3. Reading a File on a Web Server........................................................................................................................... 1153

Section 24.4. Establishing a Simple Server Using Stream Sockets........................................................................................... 1157

Section 24.5. Establishing a Simple Client Using Stream Sockets........................................................................................... 1158

Section 24.6. Client/Server Interaction with Stream Socket Connections............................................................................... 1159

Section 24.7. Connectionless Client/Server Interaction with Datagrams................................................................................. 1171

Section 24.8. Client/Server Tic-Tac-Toe Using a Multithreaded Server.................................................................................. 1178

Section 24.9. Security and the Network.................................................................................................................................... 1193

Section 24.10. [Web Bonus] Case Study: DeitelMessenger Server and Client......................................................................... 1194

Section 24.11. Wrap-Up............................................................................................................................................................. 1194

Summary....................................................................................................................................................................................1194

Terminology...............................................................................................................................................................................1196

Self-Review Exercises................................................................................................................................................................ 1197

Answers to Self-Review Exercises............................................................................................................................................. 1197

Exercises.................................................................................................................................................................................... 1198

Chapter 25. Accessing Databases with JDBC.......................................... 1201

Section 25.1. Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................1202

Section 25.2. Relational Databases...........................................................................................................................................1203

Section 25.3. Relational Database Overview: The books Database......................................................................................... 1204

Section 25.4. SQL...................................................................................................................................................................... 1207

Section 25.5. Instructions for installing MySQL and MySQL Connector/J............................................................................. 1216

Section 25.6. Instructions for Setting Up a MySQL User Account........................................................................................... 1217

Section 25.7. Creating Database books in MySQL....................................................................................................................1218

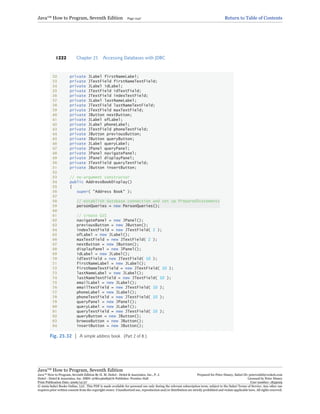

Section 25.8. Manipulating Databases with JDBC................................................................................................................... 1219

Section 25.9. RowSet Interface................................................................................................................................................. 1236

Section 25.10. Java DB/Apache Derby..................................................................................................................................... 1239

Section 25.11. PreparedStatements...........................................................................................................................................1254

Section 25.12. Stored Procedures..............................................................................................................................................1256

Section 25.13. Transaction Processing......................................................................................................................................1256

Section 25.14. Wrap-Up.............................................................................................................................................................1257

Section 25.15. Web Resources and Recommended Readings.................................................................................................. 1257

Summary....................................................................................................................................................................................1259

Terminology.............................................................................................................................................................................. 1264

Self-Review Exercise................................................................................................................................................................. 1265

Answers to Self-Review Exercise.............................................................................................................................................. 1265

Exercises.................................................................................................................................................................................... 1265

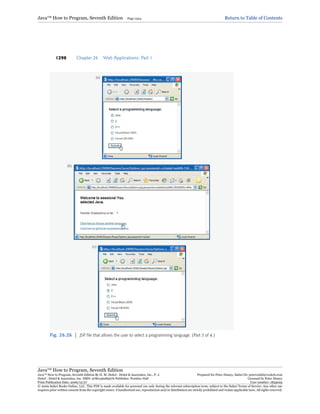

Chapter 26. Web Applications: Part 1.....................................................1268

Section 26.1. Introduction.........................................................................................................................................................1269

Section 26.2. Simple HTTP Transactions.................................................................................................................................1270

Section 26.3. Multitier Application Architecture......................................................................................................................1272

Section 26.4. Java Web Technologies.......................................................................................................................................1273

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-9-320.jpg)

![xxvi Preface

• We updated Chapter 25, Accessing Databases with JDBC, to include JDBC 4

and to use the new Java DB/Apache Derby database management system, in ad-

dition to MySQL. The chapter features an OO case study on developing a data-

base-driven address book that demonstrates prepared statements and JDBC 4’s

automatic driver discovery.

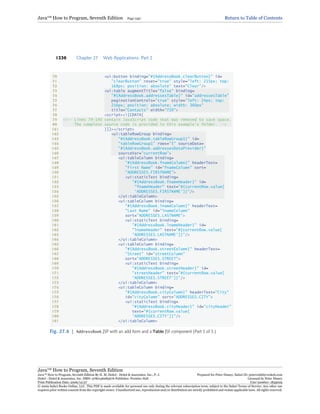

• We added Chapters 26 and 27, Web Applications: Parts 1 and 2, which intro-

duce JavaServer Faces (JSF) technology and use it with Sun Java Studio Creator

2 to build web applications quickly and easily. Chapter 26 includes examples on

building web application GUIs, handling events, validating forms and session

tracking. The JSF material replaces our previous chapters on servlets and JavaSer-

ver Pages (JSP).

• We added Chapter 27, Web Applications: Part 2, that discusses developing Ajax-

enabled web applications, using JavaServer Faces and Java BluePrints technology.

The chapter features a database-driven multitier web address book application

that allows users to add contacts, search for contacts and display contacts’ ad-

dresses on Google™ Maps. This Ajax-enabled application gives the reader a real

sense of Web 2.0 development. The application uses Ajax-enabled JSF compo-

nents to suggest contact names while the user types a name to locate, and to dis-

play a located address on a Google Map.

• We added Chapter 28, JAX-WS Web Services, which uses a tools-based approach

to creating and consuming web services—a signature Web 2.0 capability. Case

studies include developing blackjack and airline reservation web services.

• We use the new tools-based approach for rapid web applications development; all

the tools are available free for download.

• We launched the Deitel Internet Business Initiative with 60 new Resource Centers

to support our academic and professional readers. Check out our new Resource

Centers (www.deitel.com/resourcecenters.html) including Java SE 6 (Mus-

tang), Java, Java Assessment and Certification, Java Design Patterns, Java EE 5,

Code Search Engines and Code Sites, Game programming, Programming Projects

and many more. Sign up for the free Deitel® Buzz Online e-mail newsletter

(www.deitel.com/newsletter/subscribe.html)—each week we announce our

latest Resource Center(s) and include other items of interest to our readers.

• We discuss key software engineering community concepts, such as Web 2.0,

Ajax, SOA, web services, open source software, design patterns, mashups, refac-

toring, extreme programming, agile software development, rapid prototyping

and more.

• We completely reworked Chapter 23, Multithreading [special thanks to Brian

Goetz and Joseph Bowbeer—co-authors of Java Concurrency in Practice, Addi-

son-Wesley, 2006].

• We discuss the new SwingWorker class for developing multithreaded user inter-

faces.

• We discuss the new Java Desktop Integration Components (JDIC), such as

splash screens and interactions with the system tray.

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 9 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-22-320.jpg)

![xxxii Preface

Terminology. We include an alphabetized list of the important terms defined in each chap-

ter. Each term also appears in the index, with its defining occurrence highlighted with a

bold, blue page number.

Self-Review Exercises and Answers. Extensive self-review exercises and answers are includ-

ed for self-study.

Exercises. Each chapter concludes with a substantial set of exercises including simple recall

of important terminology and concepts; identifying the errors in code samples, writing in-

dividual program statements; writing small portions of methods and Java classes; writing

complete methods, Java classes and programs; and building major term projects. The large

number of exercises enables instructors to tailor their courses to the unique needs of their

students and to vary course assignments each semester. Instructors can use these exercises

to form homework assignments, short quizzes, major examinations and term projects.

[NOTE: Please do not write to us requesting access to the Prentice Hall Instructor’s Re-

source Center. Access is limited strictly to college instructors teaching from the book.

Instructors may obtain access only through their Prentice Hall representatives.] Be sure

to check out our Programming Projects Resource Center (http://www.deitel.com/Pro-

grammingProjects/) for lots of additional exercise and project possibilities.

Thousands of Index Entries. We have included an extensive index which is especially useful

when you use the book as a reference.

“Double Indexing” of Java Live-Code Examples. For every source-code program in the

book, we index the figure caption both alphabetically and as a subindex item under “Ex-

amples.” This makes it easier to find examples using particular features.

Student Resources Included with Java How to Program, 7/e

A number of for-sale Java development tools are available, but you do not need any of

these to get started with Java. We wrote Java How to Program, 7/e using only the new free

Java Standard Edition Development Kit (JDK), version 6.0. The current JDK version can

be downloaded from Sun’s Java website java.sun.com/javase/downloads/index.jsp.

This site also contains the JDK documentation downloads.

The CDs that accompany Java How to Program, 7/e contain the NetBeans™ 5.5 Inte-

grated Development Environment (IDE) for developing all types of Java applications and

Sun Java™ Studio Creator 2 Update 1 for web-application development. Windows and

Linux versions of MySQL® 5.0 Community Edition 5.0.27 and MySQL Connector/J

5.0.4 are provided for the database processing performed in Chapters 25–28.

The CD also contains the book’s examples and a web page with links to the Deitel &

Associates, Inc. website and the Prentice Hall website. This web page can be loaded into

a web browser to afford quick access to all the resources.

You can find additional resources and software downloads in our Java SE 6 (Mustang)

Resource Center at:

www.deitel.com/JavaSE6Mustang/

Java Multimedia Cyber Classroom, 7/e

Java How to Program, 7/e includes a free, web-based, audio-intensive interactive multime-

dia ancillary to the book—The Java Multimedia Cyber Classroom, 7/e—available with new

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 15 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-28-320.jpg)

![xl Before You Begin

examples to the C: drive directly and refer to this drive throughout the text. You

may choose to save your files to a different drive based on your computer’s set up,

the setup in your school’s lab or personal preferences. If you are working in a

computer lab, please see your instructor for more information to confirm where

the examples should be saved.]

Changing the Read-Only Property of Files

The example files you copied to your computer from the CD are read-only. Next, you will

remove the read-only property so you can modify and run the examples.

1. Opening the Properties dialog. Right click the examples directory and select

Properties from the menu. The examples Properties dialog appears (Fig. 3).

2. Changing the read-only property. In the Attributes section of this dialog, click the

box next to Read-only to remove the check mark (Fig. 4). Click Apply to apply

the changes.

3. Changing the property for all files. Clicking Apply will display the Confirm At-

tribute Changes window (Fig. 5). In this window, click the radio button next to

Apply changes to this folder, subfolders and files and click OK to remove the read-

only property for all of the files and directories in the examples directory.

Fig. 2 | Copying the examples directory.

Select CopyRight click the examples directory

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 23 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-36-320.jpg)

![Setting the PATH Environment Variable xliii

Microsoft Windows. This particular dialog is from a computer running Mi-

crosoft Windows XP. Your dialog might include different information.]

2. Opening the Environment Variables dialog. Select the Advanced tab at the top of

the System Properties dialog (Fig. 7). Click the Environment Variables button to

display the Environment Variables dialog (Fig. 8).

3. Editing the PATH variable. Scroll down inside the System variables box to select

the PATH variable. Click the Edit button. This will cause the Edit System Variable

dialog to appear (Fig. 9).

Fig. 7 | Advanced tab of System Properties dialog.

Fig. 8 | Environment Variables dialog.

Select the

Advanced tab

Click the Environment

Variables button

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 26 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-39-320.jpg)

![1.13 Typical Java Development Environment 13

javase/6/download.jsp. Carefully follow the installation instructions for the JDK provided

in the Before You Begin section of this book (or at java.sun.com/javase/6/webnotes/

install/index.html) to ensure that you set up your computer properly to compile and execute

Java programs. You may also want to visit Sun’s New to Java Center at:

java.sun.com/developer/onlineTraining/new2java/index.html

[Note: This website provides installation instructions for Windows, Linux and Mac OS X.

If you are not using one of these operating systems, refer to the manuals for your system’s

Java environment or ask your instructor how to accomplish these tasks based on your com-

puter’s operating system. In addition, please keep in mind that web links occasionally

break as companies evolve their websites. If you encounter a problem with this link or any

other links referenced in this book, please check www.deitel.com for errata and please no-

tify us by e-mail at deitel@deitel.com. We will respond promptly.]

Phase 1: Creating a Program

Phase 1 consists of editing a file with an editor program (normally known simply as an

editor). You type a Java program (typically referred to as source code) using the editor,

make any necessary corrections and save the program on a secondary storage device, such

as your hard drive. A file name ending with the .java extension indicates that the file con-

tains Java source code. We assume that the reader knows how to edit a file.

Two editors widely used on Linux systems are vi and emacs. On Windows, a simple

editing program like Windows Notepad will suffice. Many freeware and shareware editors

are also available for download from the Internet on sites like www.download.com.

For organizations that develop substantial information systems, integrated develop-

ment environments (IDEs) are available from many major software suppliers, including

Sun Microsystems. IDEs provide tools that support the software development process,

including editors for writing and editing programs and debuggers for locating logic errors.

Popular IDEs include Eclipse (www.eclipse.org), NetBeans (www.netbeans.org),

JBuilder (www.borland.com), JCreator (www.jcreator.com), BlueJ (www.blueJ.org),

jGRASP (www.jgrasp.org) and jEdit (www.jedit.org). Sun Microsystems’s Java Studio

Enterprise (developers.sun.com/prodtech/javatools/jsenterprise/index.jsp) is an

enhanced version of NetBeans. [Note: Most of our example programs should operate prop-

erly with any Java integrated development environment that supports the JDK 6.]

Phase 2: Compiling a Java Program into Bytecodes

In Phase 2, the programmer uses the command javac (the Java compiler) to compile a

program. For example, to compile a program called Welcome.java, you would type

javac Welcome.java

in the command window of your system (i.e., the MS-DOS prompt in Windows 95/98/

ME, the Command Prompt in Windows NT/2000/XP, the shell prompt in Linux or the

Terminal application in Mac OS X). If the program compiles, the compiler produces a

.class file called Welcome.class that contains the compiled version of the program.

The Java compiler translates Java source code into bytecodes that represent the tasks

to execute in the execution phase (Phase 5). Bytecodes are executed by the Java Virtual

Machine (JVM)—a part of the JDK and the foundation of the Java platform. A virtual

machine (VM) is a software application that simulates a computer, but hides the under-

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 40 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-53-320.jpg)

![1.14 Notes about Java and Java How to Program, 7/e 15

This would cause the Java program to display an error message. If this occurs, you would

have to return to the edit phase, make the necessary corrections and proceed through the

remaining phases again to determine that the corrections fix the problem(s). [Note: Most

programs in Java input or output data. When we say that a program displays a message,

we normally mean that it displays that message on your computer’s screen. Messages and

other data may be output to other devices, such as disks and hardcopy printers, or even to

a network for transmission to other computers.]

Common Programming Error 1.1

Errors like division by zero occur as a program runs, so they are called runtime errors or

execution-time errors. Fatal runtime errors cause programs to terminate immediately without

having successfully performed their jobs. Nonfatal runtime errors allow programs to run to com-

pletion, often producing incorrect results. 1.1

1.14 Notes about Java and Java How to Program, 7/e

Java is a powerful programming language. Experienced programmers sometimes take

pride in creating weird, contorted, convoluted usage of a language. This is a poor program-

ming practice. It makes programs more difficult to read, more likely to behave strangely,

more difficult to test and debug, and more difficult to adapt to changing requirements.

This book stresses clarity. The following is our first Good Programming Practice tip.

Good Programming Practice 1.1

Write your Java programs in a simple and straightforward manner. This is sometimes referred

to as KIS (“keep it simple”). Do not “stretch” the language by trying bizarre usages. 1.1

You have heard that Java is a portable language and that programs written in Java can

run on many different computers. In general, portability is an elusive goal.

Portability Tip 1.2

Although it is easier to write portable programs in Java than in most other programming lan-

guages, differences between compilers, JVMs and computers can make portability difficult to

achieve. Simply writing programs in Java does not guarantee portability. 1.2

Error-Prevention Tip 1.1

Always test your Java programs on all systems on which you intend to run them, to ensure that

they will work correctly for their intended audiences. 1.1

We audited our presentation against Sun’s Java documentation for completeness and

accuracy. However, Java is a rich language, and no textbook can cover every topic. A web-

based version of the Java API documentation can be found at java.sun.com/javase/6/

docs/api/index.html or you can download this documentation to your own computer

from java.sun.com/javase/6/download.jsp. For additional technical details on many

aspects of Java development, visit java.sun.com/reference/docs/index.html.

Good Programming Practice 1.2

Read the documentation for the version of Java you are using. Refer to it frequently to be sure

you are aware of the rich collection of Java features and are using them correctly. 1.2

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 42 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-55-320.jpg)

![16 Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, the Internet and the Web

Good Programming Practice 1.3

Your computer and compiler are good teachers. If, after carefully reading your Java documenta-

tion, you are not sure how a feature of Java works, experiment and see what happens. Study each

error or warning message you get when you compile your programs (called compile-time errors

or compilation errors), and correct the programs to eliminate these messages. 1.3

Software Engineering Observation 1.4

Some programmers like to read the source code for the Java API classes to determine how the

classes work and to learn additional programming techniques. 1.3

1.15 Test-Driving a Java Application

In this section, you’ll run and interact with your first Java application. You’ll begin by run-

ning an ATM application that simulates the transactions that take place when using an

ATM machine (e.g., withdrawing money, making deposits and checking account balanc-

es). You’ll learn how to build this application in the optional, object-oriented case study

included in Chapters 1–8 and 10. Figure 1.10 at the end of this section suggests other in-

teresting applications that you may also want to test-drive after completing the ATM test-

drive. For the purpose of this section, we assume you are running Microsoft Windows.

In the following steps, you’ll run the application and perform various transactions.

The elements and functionality you see in this application are typical of what you’ll learn

to program in this book. [Note: We use fonts to distinguish between features you see on a

screen (e.g., the Command Prompt) and elements that are not directly related to a screen.

Our convention is to emphasize screen features like titles and menus (e.g., the File menu)

in a semibold sans-serif Helvetica font and to emphasize non-screen elements, such as file

names or input (e.g., ProgramName.java) in a sans-serif Lucida font. As you have

already noticed, the defining occurrence of each term is set in bold blue. In the figures in

this section, we highlight in yellow the user input required by each step and point out sig-

nificant parts of the application with lines and text. To make these features more visible,

we have modified the background color of the Command Prompt windows.]

1. Checking your setup. Read the Before You Begin section of the book to confirm

that you have set up Java properly on your computer and that you have copied

the book’s examples to your hard drive.

2. Locating the completed application. Open a Command Prompt window. This can

be done by selecting Start > All Programs > Accessories > Command Prompt.

Change to the ATM application directory by typing cd C:examplesch01ATM,

then press Enter (Fig. 1.2). The command cd is used to change directories.

Fig. 1.2 | Opening a Windows XP Command Prompt and changing directories.

File location of the ATM application

Using the cd command to

change directories

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 43 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-56-320.jpg)

![1.15 Test-Driving a Java Application 17

3. Running the ATM application. Type the command java ATMCaseStudy (Fig. 1.3)

and press Enter. Recall that the java command, followed by the name of the ap-

plication’s .class file (in this case, ATMCaseStudy), executes the application. Spec-

ifying the .class extension when using the java command results in an error.

[Note: Java commands are case sensitive. It is important to type the name of this

application with a capital A, T and M in “ATM,” a capital C in “Case” and a cap-

ital S in “Study.” Otherwise, the application will not execute.] If you receive the

error message, “Exception in thread "main" java.lang.NoClassDefFound-

Error: ATMCaseStudy," your system has a CLASSPATH problem. Please refer to the

Before You Begin section of the book for instructions to help you fix this problem.

4. Entering an account number. When the application first executes, it displays a

"Welcome!" greeting and prompts you for an account number. Type 12345 at the

"Please enter your account number:" prompt (Fig. 1.4) and press Enter.

5. Entering a PIN. Once a valid account number is entered, the application displays

the prompt "Enter your PIN:". Type "54321" as your valid PIN (Personal Iden-

tification Number) and press Enter. The ATM main menu containing a list of

options will be displayed (Fig. 1.5).

Fig. 1.3 | Using the java command to execute the ATM application.

Fig. 1.4 | Prompting the user for an account number.

Fig. 1.5 | Entering a valid PIN number and displaying the ATM application’s main menu.

Enter account number promptATM welcome message

ATM main menuEnter valid PIN

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 44 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-57-320.jpg)

![18 Chapter 1 Introduction to Computers, the Internet and the Web

6. Viewing the account balance. Select option 1, "View my balance", from the

ATM menu (Fig. 1.6). The application then displays two numbers—the Avail-

able balance ($1000.00) and the Total balance ($1,200.00). The available

balance is the maximum amount of money in your account which is available for

withdrawal at a given time. In some cases, certain funds, such as recent deposits,

are not immediately available for the user to withdraw, so the available balance

may be less than the total balance, as it is here. After the account balance infor-

mation is shown, the application’s main menu is displayed again.

7. Withdrawing money from the account. Select option 2, "Withdraw cash", from

the application menu. You are then presented (Fig. 1.7) with a list of dollar

amounts (e.g., 20, 40, 60, 100 and 200). You are also given the option to cancel

the transaction and return to the main menu. Withdraw $100 by selecting option

4. The application displays "Please take your cash now." and returns to the

main menu. [Note: Unfortunately, this application only simulates the behavior of

a real ATM and thus does not actually dispense money.]

Fig. 1.6 | ATM application displaying user account balance information.

Fig. 1.7 | Withdrawing money from the account and returning to the main menu.

Account balance information

ATM withdrawal menu

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 45 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-58-320.jpg)

![1.17 Web 2.0 25

Answers to Section 1.16 Self-Review Exercises

1.1 [Note: Answers may vary.] a) A television’s attributes include the size of the screen, the num-

ber of colors it can display, its current channel and its current volume. A television turns on and off,

changes channels, displays video and plays sounds. b) A coffee maker’s attributes include the maxi-

mum volume of water it can hold, the time required to brew a pot of coffee and the temperature of

the heating plate under the coffee pot. A coffee maker turns on and off, brews coffee and heats cof-

fee. c) A turtle’s attributes include its age, the size of its shell and its weight. A turtle walks, retreats

into its shell, emerges from its shell and eats vegetation.

1.2 c.

1.3 b.

1.17 Web 2.0

The web literally exploded in the mid-to-late 1990s, but hard times hit in the early 2000s

due to the dot com economic bust. The resurgence that began in 2004 or so, has been

named Web 2.0. The first Web 2.0 Conference was held in 2004. A year into its life, the

term “Web 2.0” garnered about 10 million hits on the Google search engine, growing to

60 million a year later. Google is widely regarded as the signature company of Web 2.0.

Some others are Craigslist (free classified listings), Flickr (photo sharing), del.icio.us (social

bookmarking), YouTube (video sharing), MySpace and FaceBook (social networking),

Salesforce (business software offered as an online service), Second Life (a virtual world),

Skype (Internet telephony) and Wikipedia (a free online encyclopedia).

At Deitel & Associates, we launched our Web 2.0-based Internet Business Initiative

in 2005. We're researching the key technologies of Web 2.0 and using them to build

Internet businesses. We're sharing our research in the form of Resource Centers at

www.deitel.com/resourcecenters.html. Each week, we announce the latest Resource

Centers in our newsletter, the Deitel® Buzz Online (www.deitel.com/newsletter/

subscribe.html). Each lists many links to free content and software on the Internet.

We include a substantial treatment of web services (Chapter 28) and introduce the

new applications development methodology of mashups (Appendix H) in which you can

rapidly develop powerful and intriguing applications by combining complementary web

services and other forms of information feeds of two or more organizations. A popular

mashup is www.housingmaps.com which combines the real estate listings of

www.craigslist.org with the mapping capabilities of Google Maps to offer maps that

show the locations of apartments for rent in a given area.

Ajax is one of the premier technologies of Web 2.0. Though the term’s use exploded

in 2005, it’s just a term that names a group of technologies and programming techniques

that have been in use since the late 1990s. Ajax helps Internet-based applications perform

like desktop applications—a difficult task, given that such applications suffer transmission

delays as data is shuttled back and forth between your computer and other computers on

the Internet. Using Ajax, applications like Google Maps have achieved excellent perfor-

mance and the look and feel of desktop applications. Although we don’t discuss “raw” Ajax

programming (which is quite complex) in this text, we do show in Chapter 27 how to

build Ajax-enabled applications using JavaServer Faces (JSF) Ajax-enabled components.

Blogs are web sites (currently about 60 million of them) that are like online diaries,

with the most recent entries appearing first. Bloggers quickly post their opinions about

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 52 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-65-320.jpg)

![2.2 A First Program in Java: Printing a Line of Text 39

Line 1

// Fig. 2.1: Welcome1.java

begins with //, indicating that the remainder of the line is a comment. Programmers insert

comments to document programs and improve their readability. This helps other people

read and understand your programs. The Java compiler ignores comments, so they do not

cause the computer to perform any action when the program is run. By convention, we

begin every program with a comment indicating the figure number and file name.

A comment that begins with // is called an end-of-line (or single-line) comment,

because the comment terminates at the end of the line on which it appears. A // comment

also can begin in the middle of a line and continue until the end of that line (as in lines 11

and 13).

Traditional comments (also called multiple-line comments), such as

/* This is a traditional

comment. It can be

split over many lines */

can be spread over several lines. This type of comment begins with the delimiter /* and

ends with */. All text between the delimiters is ignored by the compiler. Java incorporated

traditional comments and end-of-line comments from the C and C++ programming lan-

guages, respectively. In this book, we use end-of-line comments.

Java also provides Javadoc comments that are delimited by /** and */. As with tra-

ditional comments, all text between the Javadoc comment delimiters is ignored by the

compiler. Javadoc comments enable programmers to embed program documentation

directly in their programs. Such comments are the preferred Java commenting format in

industry. The javadoc utility program (part of the Java SE Development Kit) reads

Javadoc comments and uses them to prepare your program’s documentation in HTML

format. We demonstrate Javadoc comments and the javadoc utility in Appendix H, Cre-

ating Documentation with javadoc. For complete information, visit Sun’s javadoc Tool

Home Page at java.sun.com/javase/6/docs/technotes/guides/javadoc/index.html.

1 // Fig. 2.1: Welcome1.java

2 // Text-printing program.

3

4 public class Welcome1

5 {

6 // main method begins execution of Java application

7 public static void main( String args[] )

8 {

9 System.out.println( "Welcome to Java Programming!" );

10

11 } // end method main

12

13 } // end class Welcome1

Welcome to Java Programming!

Fig. 2.1 | Text-printing program.

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 66 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-79-320.jpg)

![42 Chapter 2 Introduction to Java Applications

Line 6

// main method begins execution of Java application

is an end-of-line comment indicating the purpose of lines 7–11 of the program. Line 7

public static void main( String args[] )

is the starting point of every Java application. The parentheses after the identifier main in-

dicate that it is a program building block called a method. Java class declarations normally

contain one or more methods. For a Java application, exactly one of the methods must be

called main and must be defined as shown in line 7; otherwise, the JVM will not execute

the application. Methods are able to perform tasks and return information when they

complete their tasks. Keyword void indicates that this method will perform a task but will

not return any information when it completes its task. Later, we will see that many meth-

ods return information when they complete their task. You will learn more about methods

in Chapters 3 and 6. For now, simply mimic main’s first line in your Java applications. In

line 7, the String args[] in parentheses is a required part of the method main’s declara-

tion. We discuss this in Chapter 7, Arrays.

The left brace, {, in line 8 begins the body of the method declaration. A corre-

sponding right brace, }, must end the method declaration’s body (line 11 of the program).

Note that line 9 in the body of the method is indented between the braces.

Good Programming Practice 2.7

Indent the entire body of each method declaration one “level” of indentation between the left

brace, {, and the right brace, }, that define the body of the method. This format makes the struc-

ture of the method stand out and makes the method declaration easier to read. 2.7

Line 9

System.out.println( "Welcome to Java Programming!" );

instructs the computer to perform an action—namely, to print the string of characters

contained between the double quotation marks (but not the quotation marks themselves).

A string is sometimes called a character string, a message or a string literal. We refer to

characters between double quotation marks simply as strings. White-space characters in

strings are not ignored by the compiler.

System.out is known as the standard output object. System.out allows Java applica-

tions to display sets of characters in the command window from which the Java applica-

tion executes. In Microsoft Windows 95/98/ME, the command window is the MS-DOS

prompt. In more recent versions of Microsoft Windows, the command window is the

Command Prompt. In UNIX/Linux/Mac OS X, the command window is called a ter-

minal window or a shell. Many programmers refer to the command window simply as the

command line.

Method System.out.println displays (or prints) a line of text in the command

window. The string in the parentheses in line 9 is the argument to the method. Method

System.out.println performs its task by displaying (also called outputting) its argument

in the command window. When System.out.println completes its task, it positions the

output cursor (the location where the next character will be displayed) to the beginning

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 69 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-82-320.jpg)

![44 Chapter 2 Introduction to Java Applications

source Centers at www.deitel.com/ResourceCenters.html, we provide links to tutorials

that help you get started with several popular Java development tools.

To prepare to compile the program, open a command window and change to the

directory where the program is stored. Most operating systems use the command cd to

change directories. For example,

cd c:examplesch02fig02_01

changes to the fig02_01 directory on Windows. The command

cd ~/examples/ch02/fig02_01

changes to the fig02_01 directory on UNIX/Linux/Max OS X.

To compile the program, type

javac Welcome1.java

If the program contains no syntax errors, the preceding command creates a new file called

Welcome1.class (known as the class file for Welcome1) containing the Java bytecodes that

represent our application. When we use the java command to execute the application,

these bytecodes will be executed by the JVM.

Error-Prevention Tip 2.3

When attempting to compile a program, if you receive a message such as “bad command or file-

name,” “javac: command not found” or “'javac' is not recognized as an internal or ex-

ternal command, operable program or batch file,” then your Java software installation was

not completed properly. If you are using the JDK, this indicates that the system’s PATH environ-

ment variable was not set properly. Please review the installation instructions in the Before You

Begin section of this book carefully. On some systems, after correcting the PATH, you may need to

reboot your computer or open a new command window for these settings to take effect. 2.3

Error-Prevention Tip 2.4

The Java compiler generates syntax-error messages when the syntax of a program is incorrect.

Each error message contains the file name and line number where the error occurred. For exam-

ple, Welcome1.java:6 indicates that an error occurred in the file Welcome1.java at line 6. The

remainder of the error message provides information about the syntax error. 2.4

Error-Prevention Tip 2.5

The compiler error message “Public class ClassName must be defined in a file called

ClassName.java” indicates that the file name does not exactly match the name of the public

class in the file or that you typed the class name incorrectly when compiling the class. 2.5

Figure 2.2 shows the program of Fig. 2.1 executing in a Microsoft® Windows® XP

Command Prompt window. To execute the program, type java Welcome1. This launches

the JVM, which loads the “.class” file for class Welcome1. Note that the “.class” file-

name extension is omitted from the preceding command; otherwise, the JVM will not exe-

cute the program. The JVM calls method main. Next, the statement at line 9 of main dis-

plays "Welcome to Java Programming!" [Note: Many environments show command

prompts with black backgrounds and white text. We adjusted these settings in our envi-

ronment to make our screen captures more readable.]

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 71 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-84-320.jpg)

![2.3 Modifying Our First Java Program 45

Error-Prevention Tip 2.6

When attempting to run a Java program, if you receive a message such as “Exception in thread

"main" java.lang.NoClassDefFoundError: Welcome1,” your CLASSPATH environment vari-

able has not been set properly. Please review the installation instructions in the Before You Begin

section of this book carefully. On some systems, you may need to reboot your computer or open a

new command window after configuring the CLASSPATH. 2.6

2.3 Modifying Our First Java Program

This section continues our introduction to Java programming with two examples that

modify the example in Fig. 2.1 to print text on one line by using multiple statements and

to print text on several lines by using a single statement.

Displaying a Single Line of Text with Multiple Statements

Welcome to Java Programming! can be displayed several ways. Class Welcome2, shown in

Fig. 2.3, uses two statements to produce the same output as that shown in Fig. 2.1. From

this point forward, we highlight the new and key features in each code listing, as shown in

lines 9–10 of this program.

Fig. 2.2 | Executing Welcome1 in a Microsoft Windows XP Command Prompt window.

You type this command to

execute the application

The program outputs to the screen

Welcome to Java Programming!

1 // Fig. 2.3: Welcome2.java

2 // Printing a line of text with multiple statements.

3

4 public class Welcome2

5 {

6 // main method begins execution of Java application

7 public static void main( String args[] )

8 {

9

10

11

12 } // end method main

13

14 } // end class Welcome2

Fig. 2.3 | Printing a line of text with multiple statements. (Part 1 of 2.)

System.out.print( "Welcome to " );

System.out.println( "Java Programming!" );

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 72 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-85-320.jpg)

![46 Chapter 2 Introduction to Java Applications

The program is similar to Fig. 2.1, so we discuss only the changes here. Line 2

// Printing a line of text with multiple statements.

is an end-of-line comment stating the purpose of this program. Line 4 begins the Welcome2

class declaration.

Lines 9–10 of method main

System.out.print( "Welcome to " );

System.out.println( "Java Programming!" );

display one line of text in the command window. The first statement uses System.out’s

method print to display a string. Unlike println, after displaying its argument, print

does not position the output cursor at the beginning of the next line in the command win-

dow—the next character the program displays will appear immediately after the last char-

acter that print displays. Thus, line 10 positions the first character in its argument (the

letter “J”) immediately after the last character that line 9 displays (the space character be-

fore the string’s closing double-quote character). Each print or println statement re-

sumes displaying characters from where the last print or println statement stopped

displaying characters.

Displaying Multiple Lines of Text with a Single Statement

A single statement can display multiple lines by using newline characters, which indicate

to System.out’s print and println methods when they should position the output cursor

at the beginning of the next line in the command window. Like blank lines, space charac-

ters and tab characters, newline characters are white-space characters. Figure 2.4 outputs

four lines of text, using newline characters to determine when to begin each new line. Most

of the program is identical to those in Fig. 2.1 and Fig. 2.3, so we discuss only the changes

here.

Welcome to Java Programming!

1 // Fig. 2.4: Welcome3.java

2 // Printing multiple lines of text with a single statement.

3

4 public class Welcome3

5 {

6 // main method begins execution of Java application

7 public static void main( String args[] )

8 {

9 System.out.println( "Welcome to Java Programming!" );

10

11 } // end method main

12

13 } // end class Welcome3

Fig. 2.4 | Printing multiple lines of text with a single statement. (Part 1 of 2.)

Fig. 2.3 | Printing a line of text with multiple statements. (Part 2 of 2.)

n n n

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 73 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-86-320.jpg)

![48 Chapter 2 Introduction to Java Applications

2.4 Displaying Text with printf

Java SE 5.0 added the System.out.printf method for displaying formatted data—the f

in the name printf stands for “formatted.” Figure 2.6 outputs the strings "Welcome to"

and "Java Programming!" with System.out.printf.

Lines 9–10

System.out.printf( "%sn%sn",

"Welcome to", "Java Programming!" );

call method System.out.printf to display the program’s output. The method call speci-

fies three arguments. When a method requires multiple arguments, the arguments are sep-

arated with commas (,)—this is known as a comma-separated list.

Good Programming Practice 2.9

Place a space after each comma (,) in an argument list to make programs more readable. 2.9

Remember that all statements in Java end with a semicolon (;). Therefore, lines 9–10

represent only one statement. Java allows large statements to be split over many lines.

However, you cannot split a statement in the middle of an identifier or in the middle of a

string.

Common Programming Error 2.7

Splitting a statement in the middle of an identifier or a string is a syntax error. 2.7

Method printf’s first argument is a format string that may consist of fixed text and

format specifiers. Fixed text is output by printf just as it would be output by print or

println. Each format specifier is a placeholder for a value and specifies the type of data to

output. Format specifiers also may include optional formatting information.

1 // Fig. 2.6: Welcome4.java

2 // Printing multiple lines in a dialog box.

3

4 public class Welcome4

5 {

6 // main method begins execution of Java application

7 public static void main( String args[] )

8 {

9

10

11

12 } // end method main

13

14 } // end class Welcome4

Welcome to

Java Programming!

Fig. 2.6 | Displaying multiple lines with method System.out.printf.

System.out.printf( "%sn%sn",

"Welcome to", "Java Programming!" );

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 75 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-88-320.jpg)

![2.5 Another Java Application: Adding Integers 49

Format specifiers begin with a percent sign (%) and are followed by a character that

represents the data type. For example, the format specifier %s is a placeholder for a string.

The format string in line 9 specifies that printf should output two strings and that each

string should be followed by a newline character. At the first format specifier’s position,

printf substitutes the value of the first argument after the format string. At each subse-

quent format specifier’s position, printf substitutes the value of the next argument in the

argument list. So this example substitutes "Welcome to" for the first %s and "Java Pro-

gramming!" for the second %s. The output shows that two lines of text were displayed.

We introduce various formatting features as they are needed in our examples.

Chapter 29 presents the details of formatting output with printf.

2.5 Another Java Application: Adding Integers

Our next application reads (or inputs) two integers (whole numbers, like –22, 7, 0 and

1024) typed by a user at the keyboard, computes the sum of the values and displays the

result. This program must keep track of the numbers supplied by the user for the calcula-

tion later in the program. Programs remember numbers and other data in the computer’s

memory and access that data through program elements called variables. The program of

Fig. 2.7 demonstrates these concepts. In the sample output, we use highlighting to differ-

entiate between the user’s input and the program’s output.

1 // Fig. 2.7: Addition.java

2 // Addition program that displays the sum of two numbers.

3

4

5 public class Addition

6 {

7 // main method begins execution of Java application

8 public static void main( String args[] )

9 {

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17 System.out.print( "Enter first integer: " ); // prompt

18

19

20 System.out.print( "Enter second integer: " ); // prompt

21

22

23

24

25

26

27 } // end method main

28

29 } // end class Addition

Fig. 2.7 | Addition program that displays the sum of two numbers. (Part 1 of 2.)

import java.util.Scanner; // program uses class Scanner

// create Scanner to obtain input from command window

Scanner input = new Scanner( System.in );

int number1; // first number to add

int number2; // second number to add

int sum; // sum of number1 and number2

number1 = input.nextInt(); // read first number from user

number2 = input.nextInt(); // read second number from user

sum = number1 + number2; // add numbers

System.out.printf( "Sum is %dn", sum ); // display sum

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 76 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-89-320.jpg)

![2.8 Decision Making: Equality and Relational Operators 59

The application of Fig. 2.15 uses six if statements to compare two integers input by

the user. If the condition in any of these if statements is true, the assignment statement

associated with that if statement executes. The program uses a Scanner to input the two

integers from the user and store them in variables number1 and number2. Then the pro-

gram compares the numbers and displays the results of the comparisons that are true.

The declaration of class Comparison begins at line 6

public class Comparison

The class’s main method (lines 9–41) begins the execution of the program. Line 12

Scanner input = new Scanner( System.in );

declares Scanner variable input and assigns it a Scanner that inputs data from the stan-

dard input (i.e., the keyboard).

Relational operators

> > x > y x is greater than y

< < x < y x is less than y

≥ >= x >= y x is greater than or equal to y

≤ <= x <= y x is less than or equal to y

1 // Fig. 2.15: Comparison.java

2 // Compare integers using if statements, relational operators

3 // and equality operators.

4 import java.util.Scanner; // program uses class Scanner

5

6 public class Comparison

7 {

8 // main method begins execution of Java application

9 public static void main( String args[] )

10 {

11 // create Scanner to obtain input from command window

12 Scanner input = new Scanner( System.in );

13

14 int number1; // first number to compare

15 int number2; // second number to compare

16

17 System.out.print( "Enter first integer: " ); // prompt

18 number1 = input.nextInt(); // read first number from user

Fig. 2.15 | Equality and relational operators. (Part 1 of 2.)

Standard algebraic

equality or relational

operator

Java equality

or relational

operator

Sample

Java

condition

Meaning of

Java condition

Fig. 2.14 | Equality and relational operators. (Part 2 of 2.)

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 86 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-99-320.jpg)

![64 Chapter 2 Introduction to Java Applications

The cash dispenser begins each day loaded with 500 $20 bills. [Note: Due to the limited

scope of this case study, certain elements of the ATM described here do not accurately

mimic those of a real ATM. For example, a real ATM typically contains a device that reads

a user’s account number from an ATM card, whereas this ATM asks the user to type the

account number on the keypad. A real ATM also usually prints a receipt at the end of a

session, but all output from this ATM appears on the screen.]

The bank wants you to develop software to perform the financial transactions initi-

ated by bank customers through the ATM. The bank will integrate the software with the

ATM’s hardware at a later time. The software should encapsulate the functionality of the

hardware devices (e.g., cash dispenser, deposit slot) within software components, but it

need not concern itself with how these devices perform their duties. The ATM hardware

has not been developed yet, so instead of writing your software to run on the ATM, you

should develop a first version of the software to run on a personal computer. This version

should use the computer’s monitor to simulate the ATM’s screen, and the computer’s key-

board to simulate the ATM’s keypad.

An ATM session consists of authenticating a user (i.e., proving the user’s identity)

based on an account number and personal identification number (PIN), followed by cre-

ating and executing financial transactions. To authenticate a user and perform transac-

tions, the ATM must interact with the bank’s account information database (i.e., an

organized collection of data stored on a computer). For each bank account, the database

stores an account number, a PIN and a balance indicating the amount of money in the

account. [Note: We assume that the bank plans to build only one ATM, so we do not need

to worry about multiple ATMs accessing this database at the same time. Furthermore, we

assume that the bank does not make any changes to the information in the database while

a user is accessing the ATM. Also, any business system like an ATM faces reasonably com-

Fig. 2.17 | Automated teller machine user interface.

Keypad

Screen

Deposit Slot

Cash Dispenser

Welcome!

Please enter your account number: 12345

Enter your PIN: 54321

Insert deposit envelope hereInsert deposit envelope hereInsert deposit envelope here

Take cash hereTake cash hereTake cash here

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition Page 91 Return to Table of Contents

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition

Java™ How to Program, Seventh Edition By H. M. Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc., P. J.

Deitel - Deitel & Associates, Inc. ISBN: 9780136085676 Publisher: Prentice Hall

Prepared for Peter Disney, Safari ID: peterwaltd@wokeh.com

Licensed by Peter Disney

Print Publication Date: 2006/12/27 User number: 1839029

© 2009 Safari Books Online, LLC. This PDF is made available for personal use only during the relevant subscription term, subject to the Safari Terms of Service. Any other use

requires prior written consent from the copyright owner. Unauthorized use, reproduction and/or distribution are strictly prohibited and violate applicable laws. All rights reserved.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/javahowtoprogram-7e-150314072615-conversion-gate01/85/Java-How-to-Program-7e-104-320.jpg)

![2.9 Examining the Requirements Document 65

plicated security issues that are beyond the scope of a first or second programming course.

We make the simplifying assumption, however, that the bank trusts the ATM to access

and manipulate the information in the database without significant security measures.]

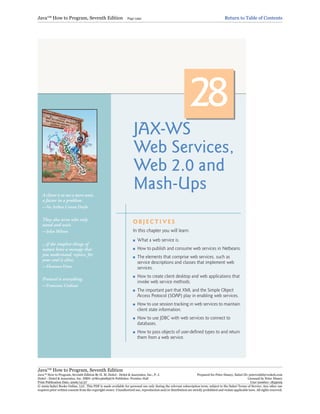

Upon first approaching the ATM (assuming no one is currently using it), the user

should experience the following sequence of events (shown in Fig. 2.17):