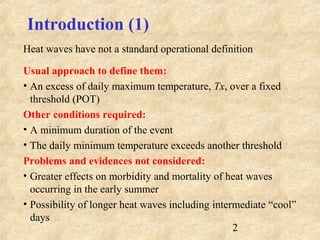

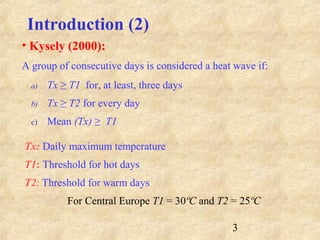

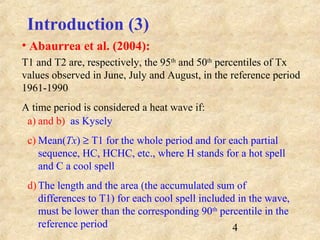

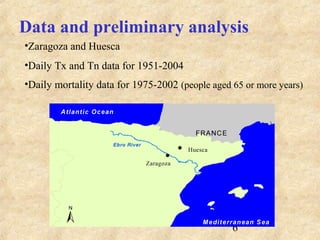

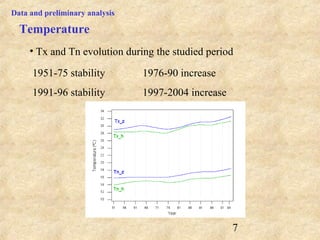

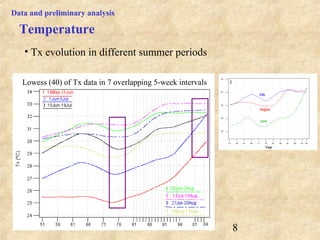

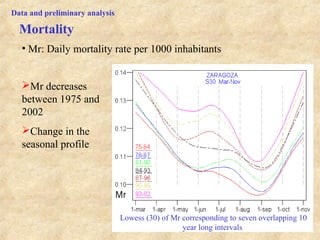

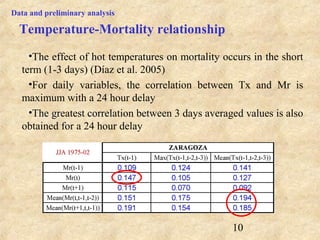

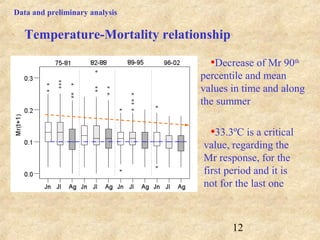

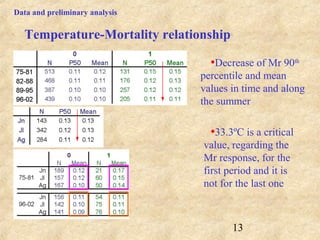

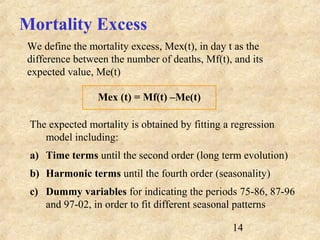

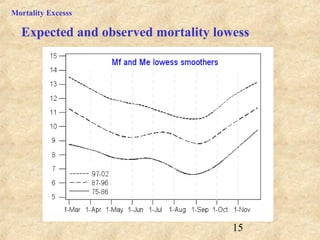

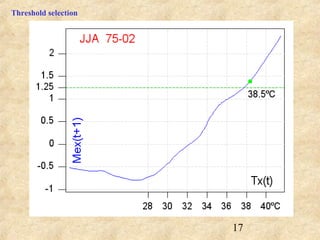

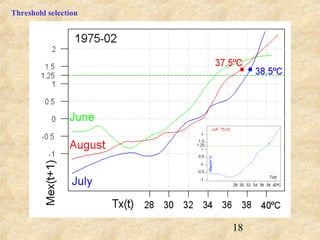

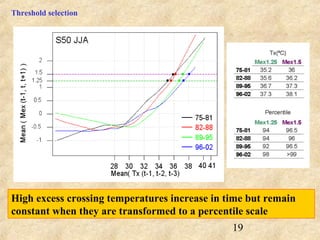

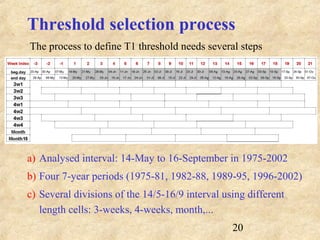

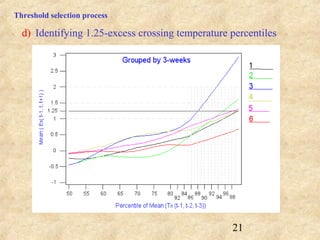

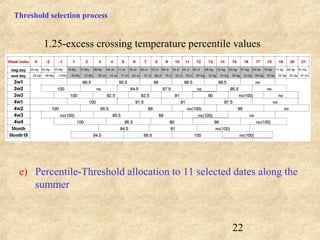

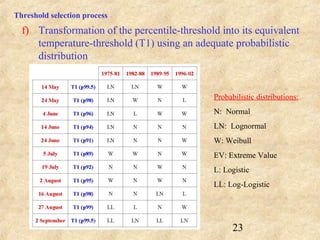

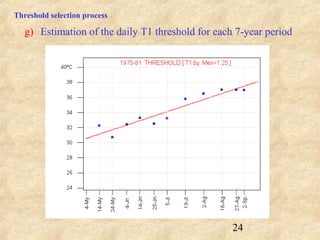

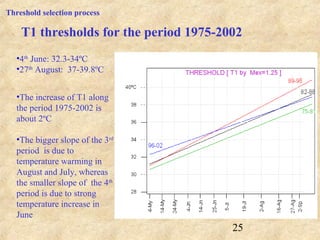

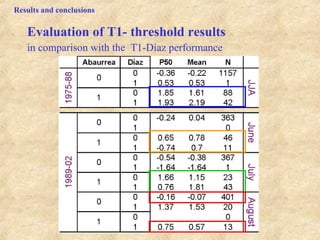

This document discusses definitions of heat waves and methods for determining heat wave thresholds. It analyzes temperature and mortality data from Zaragoza and Huesca, Spain from 1951-2004. A multi-step process is used to define a threshold temperature T1 based on identifying temperature percentiles associated with mortality excesses across time periods. T1 thresholds increase along summer months from 1975-2002 but remain constant when expressed as percentiles. The defined T1 thresholds generally perform better than an alternative definition for identifying periods of elevated mortality risk.