Is there an energy-efficiency gap in China? Evidence from an information experiment

- 1. Is There an Energy-Efficiency Gap in China? Evidence from an Information Experiment Graham Beattie∗ , Iza Ding† , and Andrea La Nauze‡ September 24, 2020 Abstract We provide evidence of an energy-efficiency gap in China. Using an incentivized field experiment, we document that providing information to consumers on the energy costs of lightbulbs significantly affects their willingness to pay for energy-efficient bulbs. Unlike previous literature, we do not find evidence that this gap is driven by biased beliefs and our experimental design allows us to rule out that changes in willingness to pay are driven purely by the salience of energy or environmental costs of lightbulbs. Rather, the results are consistent with consumers being risk averse and uncertain about the benefits of more energy-efficient appliances. ∗ Department of Economics, Loyola Marymount University, 1 LMU Drive, Los Angeles, CA, 90066 † Department of Political Science, University of Pittsburgh, Wesley Posvar Hall, Pittsburgh, PA 15260 ‡ Department of Economics, University of Pittsburgh, Wesley Posvar Hall, Pittsburgh, PA 15260 Email addresses: graham.beattie@lmu.edu, yued30@pitt.edu, and lanauze@pitt.edu. We acknowledge funding from the University of Pittsburgh Social Science Research Initiative. We thank participants at the Association for Environmental and Resource Economists annual meeting and the Advances for Field Experiment Workshop for helpful comments. All errors, omissions, and views are our own. The pre-analysis plan for the experiment was filed in the AEA registry with the ID AEARCTR-0003096. The project was approved by the IRB at the University Pittsburgh on June 29, 2018 with the approval number PRO18050119. 1

- 2. 1 Introduction The overwhelming share of growth in global energy demand in coming years is expected to come from non-OECD countries. Wolfram et al. (2012) argue that household energy consumption, via the purchase of new appliances and motor vehicles, will account for a significant proportion of the growth in non-OECD energy consumption. Despite the promise of significant economic benefits, growth in energy consumption can also lead to increases in harmful local air pollutants and greenhouse gas emissions. As in the developed world, energy efficiency is seen as a key part of the policy response to these challenges. Increasing the energy efficiency of appliances and motor vehicles may lead to significant welfare benefits. However, increasing residential energy efficiency requires more than technological improvement – in the absence of bans, individuals and households must choose to purchase more energy-efficient products. Along with the social benefit from reducing overall emissions, this choice often involves private costs that are higher initially and lower in the longer term based on the longevity of the products and reduced energy use. Frictions or mental gaps may lead to households not accurately evaluating this tradeoff, leading to suboptimal consumption of energy-efficient products – a concept that has been labeled the energy-efficiency gap. The possibility of this gap drives a raft of policy measures in the developed world including minimum standards, labeling, tax rebates and other incen- tive programs. However, there is substantial disagreement about the existence, magnitude, and underlying causes of the gap (Handel and Schwartzstein, 2018; Allcott and Greenstone, 2012; Gerarden et al., 2017) and a dearth of evidence outside the developed world (Fowlie and Meeks, 2020). In this paper we report the results of a field experiment to estimate the magnitude of the gap in urban China. The Chinese context is particularly important - as China has expe- rienced rapid industrialization and economic growth, electricity use has grown accordingly. Between 2000 and 2014, electricity use per capita in China quadrupled and it became the 1

- 3. largest consumer of electricity.1 Yet this electricity is also associated with extreme levels of pollution, which has attracted considerable domestic and international attention. Against this backdrop, the Chinese government has implemented a range of energy-efficiency policies, including policy bans on some incandescent bulbs. Allcott and Taubinsky (2015) find that the energy-efficiency gap is insufficient to justify incandescent lightbulb bans in the United States. We set out to evaluate the magnitude of the gap in China. In a within-subject experiment, we find that informing subjects about the relative costs of using energy-efficient light emitting diode (LED) lightbulbs increased their willingness to pay for these bulbs by 11 Yuan ($1.50). We chose to study the lightbulb market for several reasons. First, lighting is a significant component of residential electricity consumption, representing up to 85% of consumption in the developing world (Mills, 2002). Second, lighting is a very common target of energy-efficiency programs (Allcott and Taubinsky, 2015). Third, information on the lifetime costs of using lightbulbs is relatively straightforward and can be easily communicated in a field setting to participants. Fourth, lightbulbs are fairly universal and replaced regularly, so subjects should be engaged with an experiment that allows them to acquire them. Finally, lightbulbs are a feasible durable good given constrained research budgets. Our experiment combines an incentivized multiple price list elicitation of willingness to pay with an information intervention outlining the relative energy costs of lightbulbs over ten years. We further differentiate our treatments by deliberately priming a random subset of subjects to consider the environmental and energy costs of the lightbulbs. We find that the energy-efficiency gap in urban China is similar to previous estimates of the gap in the United States. However unlike previous studies, our results are not consistent with the hypothesis that biased beliefs about long term cost savings cause underconsumption of energy-efficient products. Without our information intervention, subjects in the experi- ment are overly optimistic about the savings from LED bulbs. Our intervention simultane- 1 Source: data.worldbank.org 2

- 4. ously decreases beliefs about the cost savings from LED lightbulbs and increases willingness to pay for these bulbs. Further, the effect of energy-efficiency information is positive even for those who were the most optimistic about the energy efficiency of LEDs. We also find that asking subjects about these savings without providing them with information does not affect their willingness to pay. This is inconsistent with the hypothesis that the energy-efficiency gap is caused by lifetime energy costs lacking salience at the time of purchase. We propose an alternative explanation for the energy-efficiency gap based on uncertainty. In a simple model, we demonstrate that an information treatment that resolves uncertainty about the benefits of energy-efficient technologies may increase willingness to pay for energy efficiency even if it has no effect on average beliefs. Consistent with this hypothesis, our information treatment significantly decreases the between-subject dispersion of beliefs. Our primary contribution is to provide the first experimental evidence of the energy- efficiency gap in China. In doing so we contribute to experimental and non-experimental literature identifying varying degrees of inattention to energy efficiency in lightbulbs (Allcott and Taubinsky, 2015), vehicles (Allcott and Knittel, 2019; Allcott and Wozny, 2014; Sallee et al., 2016; Grigolon et al., 2018), home heating (Myers, 2019) and appliances (Houde, 2018). To date this literature has focused on the developed world and in particular, on analyses of the gap in the United States. Exceptions are Toledo (2016) who uses an experiment to investigate take up of LED lightbulbs in response to price and non price mechanisms in Brazil and Carranza and Meeks (2020) who experimentally identify the effect of energy efficiency on electric reliability in the Kyrgyz Republic. In China, prior work has focused on eliciting attitudes and measuring technology adoption (Ma et al., 2013; Dianshu et al., 2010). More generally, our results point to an under-explored mechanism of information cam- paigns: the resolution of uncertainty regarding product attributes. Unlike previous litera- ture, we find that subjects overestimate the savings of LED lightbulbs, but increase their willingness to pay for those bulbs when informed about actual cost savings. In contrast, Allcott and Taubinsky (2015) find evidence that information on energy efficiency operates 3

- 5. at least partially through changes in average beliefs. While Allcott and Knittel (2019) find no systematic evidence of consumers underestimating vehicle efficiency they also find no ev- idence of an energy-efficiency gap. Similarly, Allcott and Sweeney (2016) find some evidence that consumers over estimate energy savings but also do not find evidence of a significant energy-efficiency gap. Our simple model illustrates how the behavior we observe is consistent with unbiased consumers being uncertain about the energy savings of LED bulbs. Sallee (2014), following Gabaix (2012), models consumers who are unbiased but uncertain about the energy savings of a product. Consumers in these models are risk-neutral so changes in uncertainty that preserve mean beliefs would have no effect on willingness to pay for energy efficiency. In ad- dition, although information may affect decisions in this model, it should not systematically increase beliefs about lifetime cost savings from energy efficiency. We show that information interventions may increase willingness to pay for the uncertain attribute even when con- sumers are mean unbiased. Our findings suggest that public information campaigns such as labeling play an important role in addressing frictions such as imperfect information, even if consumers are unbiased. Finally, we contribute to a recent literature on experimenter demand and the Hawthorne effect. We rule out that the gap we estimate is driven purely by highlighting the existence of energy or environmental costs. In two of our treatment arms we deliberately primed participants to think about these costs. We find no evidence that increasing the salience of the costs of energy consumption in this manner changes willingness to pay for lightbulbs. We find weak evidence that increasing the salience of the environmental consequences of energy consumption may alter willingness to pay, but the magnitude of this effect is small relative to the effect of energy consumption information. These results are consistent with recent evidence that experimenter demand and the Hawthorne effect may not be a significant concern in field settings (De Quidt et al., 2018; Mummolo and Peterson, 2019). The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides context for energy- 4

- 6. efficiency policy in China. Section 3 outlines a conceptual framework for the effects of an information intervention. Sections 4 provides information on the design and implementation of the experiment. Section 5 presents the results and section 6 concludes. 2 Background We study the energy-efficiency gap in urban China, which is a particularly important setting to understand. The tensions between growth and pollution are highly salient in urban China. In 2007 China surpassed the United States as the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter and air pollution in urban areas has caused intense international scrutiny and domestic outcry. However, despite the focus of many citizens on urban pollution, the Chinese government also faces pressure to maintain the strong economic growth associated with its rapid development. In response to the growing costs of pollution, the Chinese government has placed greater emphasis on environmental policy. As a result, China is now the world’s largest investor in the research, development, and deployment of low-carbon energy technologies (Helveston and Nahm, 2019). The simultaneous need to maintain growth and reduce emissions have made energy efficiency particularly attractive for the Chinese government. The 12th Five- Year Plan (2011-2015) explicitly identified energy efficiency and clean energy as important areas of investment. Lighting, in particular, has received substantial political attention and standards on household appliances including lighting have become increasingly stringent in recent years. In 2011, China banned the import and sales of 100-Watt incandescent bulbs; this was followed by a 2014 ban on 60-Watt incandescent bulbs. A ban on all incandescent bulbs greater than 15W was planned at the time the 2014 ban, but was never enacted. The welfare impacts of these bans are potentially large. Yet to date the effects of bans, and energy-efficiency policies more generally, are poorly understood in China and in other countries at similar stages of development. In Section 4 we outline details of the experiment that allows us to measure the energy-efficiency gap in China. Before we do so, in the next 5

- 7. section we outline a conceptual framework for the experiment. 3 Conceptual framework A consumer i has a budget Zi out of which she has to purchase an energy-consuming durable good. She has two options: a conventional, not energy-efficient model (N), and an energy- efficient model (E). Each good has a price which are pN and pE respectively, where pN < pE . Each good also has a lifetime energy cost. The present value of the lifetime energy cost of the conventional good is cN i , which is known to the consumer and is a function of usage, energy prices, and the consumer’s discount rate.2 The present value of the lifetime energy cost (cE i ) of the energy-efficient product is not known to the consumer, but instead is distributed with mean cE i and variance σ2 i . The true value of cE i is denoted cE i ∗ . The lifetime energy costs of the good may not be fully salient to the consumer when she is making the purchase decision. The salience of the cost is given by γi ∈ [0, 1] where a consumer with γi = 0 ignores the lifetime energy costs entirely and a consumer with γi = 1 fully considers them. Consumer i’s utility (Ui(x)) is given by the money she expects to have left over after buying and operating the durable good (where Ui (x) > 0). Consumers are risk averse, so Ui (x) < 0. Consumer i chooses to buy the conventional good if Ui(E) < Ui(N) U(Zi − pE − γicE i ) < U(Zi − pN − γicN i ) (1) and chooses to buy the energy-efficient good if U(Zi − pE − γicE i ) > U(Zi − pN − γicN i ) (2) 2 The assumption that the consumer knows the energy cost of the conventional good simplifies the anal- ysis, but it can be relaxed without altering the main results. 6

- 8. If consumer i were fully informed and attentive, she would buy the conventional good if U(Zi − pE − cE i ∗ ) < U(Zi − pN − cN i ) (3) and the energy-efficient good if U(Zi − pE − cE i ∗ ) > U(Zi − pN − cN i ) (4) An energy-efficiency gap occurs if consumers choose not to buy the energy-efficient product, but would if they were fully informed and attentive. Formally, this occurs if there are more consumers for whom both (1) and (4) hold than for whom both (2) and (3) hold. This can be caused by one or more of the following: • Consumers’ beliefs about cE i are biased upwards, so that they underestimate the lifetime savings from the energy-efficient product. U(Zi − pE − γicE i ) is decreasing in cE i , so as cE i increases, (1) is more likely to hold. • Consumers are uncertain about cE i . Since U (Zi − pE − γicE i ) < 0, U(Zi − pN − γicE i ) is decreasing in σ2 i , so (1) is more likely to hold for high values of σ2 i . • The lifetime costs are not salient. Since Zi − pE < Zi − pN , we know that U(Zi − pE − γicE i ) − U(Zi − pN − γicN i ) is decreasing in γ for sufficiently low values of cE i and σ2 i . Further, if cE i and σ2 i are large enough so that U(Zi − pE − γicE i ) − U(Zi − pN − γicN i ) is increasing in γ, then (1) always holds. Therefore, (1) is more likely to hold for lower values of γi. Providing consumers with information about the lifetime energy costs may reduce σ2 i , increase γi, and, if cE i > cE i ∗ , reduce cE i . It could reduce the energy-efficiency gap regardless of which of these three factors cause it, so observing that information makes consumers more likely to buy energy-efficient products does not shed light on the underlying cause of the energy-efficiency gap, while our experimental setup does. 7

- 9. 4 Experiment design and implementation Our experiment consists of 7 modules.3 The treatments consisted of including and changing the order of the modules. Modules 1 and 4 (provided to all participants) elicited willingness to pay for an LED lightbulb relative to two incandescent lightbulbs. To incentivize truthful revelation, each participant was allocated a budget of 20 Yuan (approximately $2.85 US) and presented with a multiple price list for the two lightbulb packages one Philips 40W equivalent LED lightbulb or two Philips 40W incandescent lightbulbs. The length of the price list was 15 and the maximum price for either bulb exhausted the budget of 20 Yuan. The order of the lightbulbs (A and B) in the price list was randomized between LED and incandescent packages. The lightbulbs were chosen to be as comparable as possible - they are visually similar and both produce brightness of 500 lumens. The point at which partici- pants switch between options reveals their willingness to pay. We elicited willingness to pay twice from each participant. At the end of the experiment the enumerators used a random number generator to draw one decision from the two elicitations and participants received the associated lightbulb and any unspent budget in cash. Module 2 (Cost Information) consisted of information on the cost of using LED and in- candescent lightbulbs over a 10 year period. Participants who received the Cost Information received a handout detailing the differences in the expected costs of lighting using the bulbs over a 10 year period. Module 3 provided participants with placebo information on different lightbulb shapes and was delivered to all participants. This module serves as an alternative to Module 2 and should not have any effect on relative willingness to pay as both bulb op- tions are the same shape. Module 5 (Cost Questions) consisted of a series of questions about the costs of using the lightbulbs. Module 6 (Environment Questions) asked participants to choose whether economic development or environmental protection was more important to them, and asked them to nominate what they thought were the main contributions to air 3 The Supplementary Appendix contains a schematic of the experimental design and the materials for each module in Chinese and English. 8

- 10. pollution by individual citizens. Finally, Module 7 (Other Questions) collected demographic information and asked questions designed to assess characteristics of participants such as their experience with purchasing lightbulbs and paying electricity bills. Our experiment includes a control group and 5 treatment groups. The control group did not receive the information about lifetime costs; 4 the Information Treatment group (T1) did receive this treatment; the Cost Priming treatment group (T2) did not receive the infor- mation treatment and the cost questions (Module 5) were asked immediately after the first elicitation of willingness-to-pay; the Environmental Priming treatment group did not receive the information and the environmental questions (T3) were asked after the first elicitation of willingness to pay; the Information + Cost Priming treatment group (T4) received the information and were asked the cost questions between the first elicitation and the infor- mation; and the Information + Environmental Priming treatment group (T5) received the information and were asked the environmental questions between the first elicitation and the information. The purpose of the Cost Priming and Environmental Priming treatments is to assess the extent to which simply drawing attention to the costs of lightbulbs or to environmental problems has a direct effect on willingness to pay for LEDs. Further, because the Cost Questions module asks participants about costs, it has the additional benefit of providing us with data about participant beliefs. Participants in all groups were asked the same questions (i.e. Modules 5 and 6) at different points in the experiment. This allows us to assess the impact of the Information treatment on beliefs about the costs of LED relative to incandescent lighting. Our experiment was implemented between April 11 and June 9, 2018 at four outdoor locations in Beijing.5 We hired and trained experienced enumerators of a local survey com- pany to field the experiment.6 Enumerators were told to approach potential respondents on 4 All groups that did not receive the information treatment received the placebo information (Module 3) 5 We selected one site within each of the four major districts in central Beijing. 6 Enumerators were trained to adhere strictly to the script. Their training included several practice rounds with a member of the research team as well as several supervised practice surveys on members of 9

- 11. the street to participate in a “consumption habits survey”. In Modules 1 and 4, we elicit relative willingness to pay for energy-efficient bulbs using an incentive compatible multiple price list. There are two well-known limitations of the multiple price list methodology. The first is the possibility that subjects choose lightbulbs non-monotonically. Subjects who did not choose monotonically by switching between the bulbs more than once were prompted by the enumerators to choose again. After being prompted 14% of participants continued to give this type of response and were excluded from the sample. The second well-known limitation of multiple price list experiments is censoring of willingness to pay. A relatively larger share (48% in the first elicitation, 63% in the second) of subjects always chose one bulb, regardless of the price. These subjects were asked a follow-up question: How much must a [...] bulb cost for you to choose [alternative] bulb? In the first elicitation, 40% of subjects with censored WTP provided a stated response, while 63% did in the second elicitation. We assign all censored subjects the median value of willingness to pay among this group. As an alternative we drop any censored respondent who did not answer the follow-up question and assign the median of the stated responses to those who provided a stated response.7 To generate balance across treatments and enumerators, at the start of each day, each enumerator was given a randomized survey ordering. Enumerators were instructed to ap- proach potential participants at random, and deliver the experiment modules according to the order indicated in their randomized list.8 We collected 1,311 valid responses. The Control group (333 subjects) and Information group (T1=333 subjects) were approximately twice as large as the Cost Priming (T2=159 subjects), Environmental Priming (T3=171 sub- jects), Information + Cost Priming (T4=161 subjects), and Information + Environmental the public. Two supervisors from the survey firm were at the research site at all times and a member of the research team was periodically present. 7 In the Supplementary Appendix we present results when we drop censored responses from the analysis and assigning each participant their stated willingness to pay. 8 We provided enumerators with 12 versions of the experiment script, for each group (control or treatment (T1-T5) there was one script where LED bulbs were Bulb 1 and one script where incandescent bulbs were Bulb 1. 10

- 12. Priming (T5=154 subjects) treatment groups. Table 1 shows that the randomization of our treatments appears to have been successful as groups are balanced on collected observable characteristics as well as baseline relative WTP for the LED bulb. 5 Results 5.1 The energy efficiency gap Our experiment consisted of three main treatments: an information treatment, a cost salience treatment, and a environmental salience treatment. A positive and significant of the infor- mation treatment would be evidence that there is an energy efficiency gap in China. To estimate treatment effects, we use the following specification: DiffWTPi = α + β1Infoi + β2CostPrimingi + β3EnvPriming + Xiγ + i (5) For each subject i, DiffWTPi represents the difference in willingness to pay between the second elicitation and the first, Infoi, CostPrimingi, and EnvPriming are binary variables indicating whether or not a subject received each treatment, and Xi is a vector of demo- graphic variables including age, gender, children, income, education, and whether the subject is responsible for their own electricity bill. As our treatments are randomized this vector of controls should only affect the precision of our estimates. Table 2 shows the results of versions of this specification where subjects who have a censored WTP are assigned the median stated response. In Columns (1) to (3) all subjects are included, while in Columns (4) to (6) subjects who had a censored WTP and did not provide a stated response are dropped. Columns (1) and (4) include no controls, Columns (2) and (5) add controls and Columns (3) and (6) include interview and location fixed effects. The different measures of willingness to pay (columns (1)-(3) vs columns (4)-(6)) yield different magnitudes however the Information treatment has a significant positive effect 11

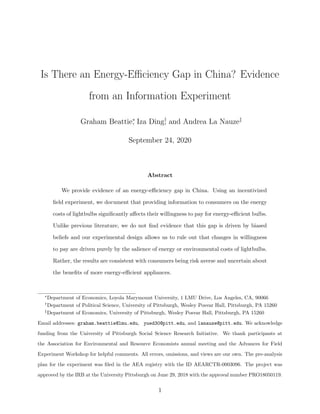

- 13. on willingness to pay across all specifications. The Environmental Priming treatment has an effect which is only significantly positive in some specifications, and the Cost Priming treatment has no significant effect on willingness to pay.9 The measure of WTP in Columns (1)-(3) is closest to the measure used by Allcott and Taubinsky (2015) and the magnitude of the effect of the information treatment (11.37 Yuan=$1.60) is not dissimilar to the $2.30 effect that Allcott and Taubinsky (2015) found. This suggests that the energy-efficiency gap in urban China is similar in magnitude to the energy-efficiency gap in the United States. 5.2 Beliefs, attention and uncertainty In our experiment, all subjects were asked to estimate the lifetime cost savings that the energy-efficient bulb provides (Module 5). Some subjects answered without seeing the in- formation treatment, either because they were in the control group, or because they were asked the cost questions prior to receiving the information treatment. Other subjects were asked about cost savings after receiving the Information treatment.10 Comparing the beliefs of these groups allows for an across-subject evaluation of the effect of information on beliefs. Figure 1 shows the distribution of beliefs of those with and without information (we refer to these groups as the informed and uninformed respectively). The distributions are bottom- coded and top-coded at -3000 and 3000. The information treatment updated beliefs towards 215 Yuan, which was the value provided in the Information treatment. There were fewer overly pessimistic subjects in the informed group – the 10th percentile of beliefs was 21 Yuan for uninformed subjects and 100 Yuan for informed – and fewer overly optimistic subjects – the 75th percentiles were 2300 Yuan and 999 Yuan. In addition, both the mean and median response are closer to 215 for the informed group and the standard deviation is smaller. 9 In the Supplementary Appendix we report all coefficients including the controls and the results of treatment effects for each of the 5 treatment groups. We find no significant interaction between Priming and Information treatments. We also include results for alternative measures of WTP. 10 Subjects were not asked about cost savings immediately after receiving the information. The placebo information module and the second elicitation of willingness-to-pay module took place between information and questions for all of these subjects. 12

- 14. Beliefs of the uninformed group were overly optimistic, so the net effect of information is to revise beliefs about the savings from an LED bulb downward.11 Figure 1 also shows that there is still dispersion in consumer beliefs about the energy efficiency of lightbulbs after the information treatment. A quarter of informed subjects estimated that the lifetime cost savings were 999 Yuan or more after being told that they were 215 Yuan and more than 10 percent said they were 3000 Yuan or more. A significant portion of subjects who received the Information treatment did not attend to, did not understand, or did not believe the information they were provided. Having information about subjects’ prior beliefs about savings allows us to test the hy- pothesis that the energy-efficiency gap is driven by biased beliefs. If the only effect driving the energy-efficiency gap is misinformed consumers – consumers do not optimize their purchases of energy-efficient products because they have biased beliefs about the lifetime cost savings – the effect of the Information treatment should be a function of prior beliefs. Specifically, subjects who are initially too pessimistic about the lifetime cost savings should experience an increase in their willingness to pay, while subjects who are initially overly optimistic should experience a decrease. Table 2 shows that the Information treatment has a significant positive effect on willing- ness to pay. Given that the sample was initially overly optimistic, this is somewhat surprising, as optimists should have their beliefs about cost savings, and thus their willingness to pay, re- vised downwards. By leveraging the fact that subjects who received the Information + Cost Priming treatment were asked about their beliefs before receiving the Information treatment, we are able to split the group into those who were initially optimistic and those who were initially pessimistic. Figure 2 shows that even these optimists increase their willingness to pay in response to information. We find that the effect of the Information treatment is con- sistently positive across subjects who are initially very optimistic (believe the savings from LED bulbs are more than 1.5 × 215 Yuan), initially very pessimistic (believe the savings 11 The mean and median of the uninformed consumers were 500 and 1032, respectively. 13

- 15. from LED bulbs are less than 0.5 × 215 Yuan), and approximately correct.12 Further, Figure 3 shows that the effect of the Information treatment does not vary significantly by initial willingness to pay. Those who are initially willing to pay more for the energy-efficient bulb still have their willingness to pay increased by the Information treatment.13 This suggests that biased beliefs is not the primary factor creating the energy-efficiency gap. A second possibility is that salience drives the energy-efficiency gap and consumers un- derinvest in energy-efficient products because the lifetime cost savings are not salient at the time of purchase. If this hypothesis is true, the Cost Priming treatment should have a pos- itive effect on willingness to pay because it increases the salience of these savings. Further, this effect should be larger for subjects with more optimistic beliefs about savings, as the savings they are reminded of to be larger. Finally, the Information treatment should have a similar positive effect as the Cost Priming treatment as it also serves to make lifetime cost savings salient for subjects. Table 2 suggests that salience is unlikely to be the factor that dominates beliefs. The effect of the Cost Priming treatment is statistically indistinguishable from zero and we can reject the hypothesis that it is equal to the effect of the Information treatment. Further, Figure 2 suggests that those who are reminded of overly pessimistic beliefs do not revise their willingness to pay upwards any less than those who are reminded of optimistic beliefs. It is possible that the primary driver of the energy-efficiency gap is salience but that the Cost Priming treatment does not close this gap. Although our experimental setup does not allow us to definitively reject this possibility, it does provide evidence that it is unlikely. If the lack of salience of lifetime cost savings is an important enough factor that closing it with the Information treatment has a large and significant effect on willingness to pay, it is reasonable to expect that drawing subjects’ attention to savings through asking directly 12 It is important to note that the 215 Yuan figure is an estimate based on projected energy prices. Therefore it is not accurate to classify a number that differs slightly from 215 Yuan as incorrect. By using a wide range of values around 215 Yuan we create groups that can be reasonably described as pessimistic, approximately correct, and optimistic. 13 The result that the effect is close to zero for the top categories in Figure 3 is largely a mechanical result of the top-coding of willingness to pay. 14

- 16. about them should have a detectable effect on willingness to pay. The remaining possibility is that a third factor, other than biased beliefs or lack of salience, is an important determinant of the energy-efficiency gap. As Section 3 illustrates, a likely candidate for this is uncertainty about cost savings. Although we do not test for uncertainty directly, the results of the experiment are con- sistent with uncertainty being the driving factor behind the energy-efficiency gap in China. The Cost Priming treatment should not reduce uncertainty since it does not provide any information. Indeed, we find that this treatment has no effect on willingness to pay. The significant effect of the Information treatment, even for initially optimistic subjects, is also consistent with uncertainty as subjects who receive the Information treatment have their uncertainty about the lifetime cost savings reduced. Providing initially optimistic subjects with information about the cost savings, even if the savings are not as large as their initial guess, may give them a basis for being willing to pay more for energy-efficient bulbs. A subject may be willing to pay more for an energy-efficient bulb if she is confident that the lifetime cost savings are 215 Yuan relative to a case where she estimates the savings are more than 215 Yuan but is not confident in her estimate. Our experimental setup does not allow us to directly test for a reduction in within-subject uncertainty. However, several pieces of suggestive evidence indicate that the information treatment reduces uncertainty. First, as Figure 1 shows, the Information treatment reduced dispersion in beliefs. Although the figure is a cross-section of subjects and does not show within-subject changes, this result is consistent with a reduction in within-subject uncer- tainty. Second, it is reasonable to hypothesize that a subject who held initial beliefs that are very different from the true value, as many of our subjects did, should be fairly uncertain about her estimate. Third, the effectiveness of the Information treatment at changing the distribution of beliefs argues that subjects must not have had strong prior beliefs and must attach credibility to the information. Taken together with the evidence against biased beliefs or salience driving the energy- 15

- 17. efficiency gap, the results of the experiment indicate that consumer uncertainty about the lifetime cost savings of energy-efficient products is the major determinant of the energy- efficiency gap. Consumers guess that energy-efficient products will save them money over the lifetime of the product and appear to consider this when making purchasing decisions. However, because they are not confident in their guess they are unwilling to invest as much in energy-efficient products as they would if they had more certainty about the lifetime energy costs. 6 Conclusion In this paper, we use an information experiment to test for an energy-efficiency gap in urban China. An energy-efficiency gap exists where consumers invest in fewer energy-efficient products than fully informed and attentive consumers would. This gap has been observed in many contexts in the developed world. Because of credit constraints and differences in preferences, energy efficiency outside the developed world is potentially different. Given the anticipated growth in energy consumption of the developing world, it is also important to understand. We perform two incentivized elicitations of relative willingness to pay for incandescent lightbulbs and energy-efficient LED lightbulbs. For the treatment group, we provide in- formation about the lifetime energy cost savings of the energy-efficient bulbs between the two elicitations. Since the treatment group is more informed about and more attentive to savings, a comparison across groups of the difference in willingness to pay between the two elicitations provides a measure of the energy-efficiency gap. We find results that are broadly consistent with previous measures taken in developed countries. However, our results point to a new mechanism behind inattention to energy efficiency. We rule out that biased beliefs or salience drive the gap that we observe, suggesting that a third factor must be the primary cause of the energy-efficiency gap. We present a 16

- 18. simple model showing that a likely candidate is uncertainty about the long term cost savings from energy efficiency and show that our results are consistent with this hypothesis. References Allcott, H. and M. Greenstone (2012): “Is there an energy efficiency gap?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26, 3–28. Allcott, H. and C. Knittel (2019): “Are consumers poorly informed about fuel econ- omy? Evidence from two experiments,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 11, 1–37. Allcott, H. and R. L. Sweeney (2016): “The role of sales agents in information dis- closure: evidence from a field experiment,” Management Science, 63, 21–39. Allcott, H. and D. Taubinsky (2015): “Evaluating behaviorally motivated policy: experimental evidence from the lightbulb market,” American Economic Review, 105, 2501– 2538. Allcott, H. and N. Wozny (2014): “Gasoline prices, fuel economy, and the energy paradox,” Review of Economics and Statistics, 96, 779–795. Carranza, E. and R. Meeks (2020): “Energy efficiency and electricity reliability,” Re- view of Economics and Statistics, Accepted. De Quidt, J., J. Haushofer, and C. Roth (2018): “Measuring and bounding experi- menter demand,” American Economic Review, 108, 3266–3302. Dianshu, F., B. K. Sovacool, and K. M. Vu (2010): “The barriers to energy effi- ciency in China: Assessing household electricity savings and consumer behavior in Liaon- ing Province,” Energy Policy, 38, 1202–1209. 17

- 19. Fowlie, M. and R. Meeks (2020): “Rethinking Energy Efficiency in the Developing World,” Review of Environmental Economics and Policy. Gabaix, X. (2012): “A sparsity-based model of bounded rationality, applied to basic con- sumer and equilibrium theory,” manuscript, New York University. Gerarden, T. D., R. G. Newell, and R. N. Stavins (2017): “Assessing the energy- efficiency gap,” Journal of Economic Literature, 55, 1486–1525. Grigolon, L., M. Reynaert, and F. Verboven (2018): “Consumer valuation of fuel costs and tax policy: Evidence from the European car market,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 10, 193–225. Handel, B. and J. Schwartzstein (2018): “Frictions or mental gaps: what’s behind the information we (don’t) use and when do we care?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 32, 155–78. Helveston, J. and J. Nahm (2019): “China’s key role in scaling low-carbon energy technologies,” Science, 366, 794–796. Houde, S. (2018): “How consumers respond to product certification and the value of energy information,” The RAND Journal of Economics, 49, 453–477. Ma, G., P. Andrews-Speed, and J. Zhang (2013): “Chinese consumer attitudes to- wards energy saving: The case of household electrical appliances in Chongqing,” Energy Policy, 56, 591–602. Mills, E. (2002): “Why we’re here: The $230-billion global lighting energy bill,” in Pro- ceedings from the 5th European Conference on Energy Efficient Lighting, held in Nice, France, Citeseer, 29–31. Mummolo, J. and E. Peterson (2019): “Demand effects in survey experiments: An empirical assessment,” American Political Science Review, 113, 517–529. 18

- 20. Myers, E. (2019): “Are home buyers inattentive? Evidence from capitalization of energy costs,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 11, 165–88. Sallee, J. M. (2014): “Rational Inattention and Energy Efficiency,” Journal of Law and Economics, 57. Sallee, J. M., S. E. West, and W. Fan (2016): “Do consumers recognize the value of fuel economy? Evidence from used car prices and gasoline price fluctuations,” Journal of Public Economics, 135, 61–73. Toledo, C. (2016): “Do environmental messages work on the poor? Experimental evi- dence from brazilian favelas,” Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, 3, 37–83. Wolfram, C., O. Shelef, and P. Gertler (2012): “How will energy demand develop in the developing world?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26, 119–38. 19

- 21. 7 Figures and Tables Figure 1: Beliefs about lifetime cost savings Notes: Figure plots density of stated beliefs of respondents regarding the 10 year energy savings of LED bulbs for (1) participants who had not received the information treatment (dashed line) and (2) participants who had received the information treatment (solid line). Stated beliefs are censored at -3000,3000. The solid vertical line at 215 represents the information provided to the participants on the expected savings. 20

- 22. Figure 2: Effect of information treatment by initial beliefs Notes: Figure plots estimated treatment effects of information by initial beliefs regarding the energy savings of LED lightbulbs. All respondents with censored WTP are assigned the median stated WTP across the censored group. Standard errors are robust. 21

- 23. Figure 3: Effect of information treatment by baseline WTP Notes: Figure plots estimated treatment effects of information by initial relative WTP for LED lightbulb. All respondents with censored WTP are assigned the median stated WTP across the censored group. Standard errors are robust. 22