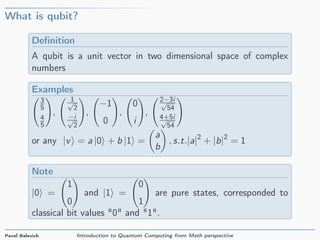

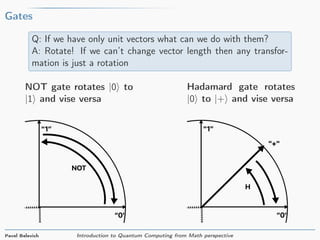

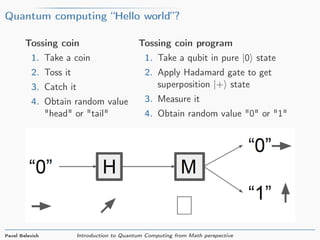

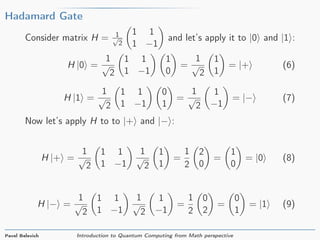

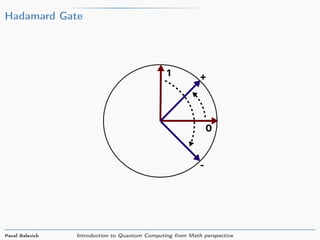

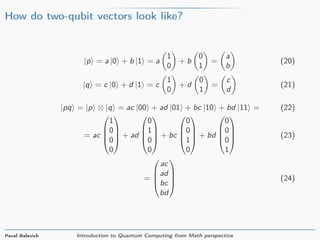

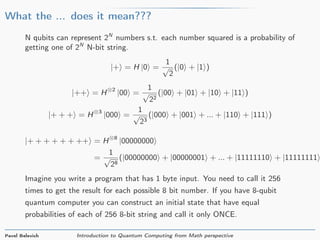

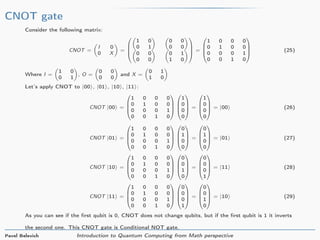

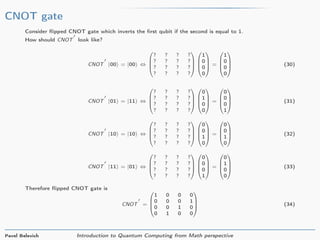

The document provides an introduction to quantum computing from a mathematical perspective. It defines a qubit as a unit vector in a two-dimensional complex vector space. Common qubit states like |0⟩ and |1⟩ are described. Basic quantum gates like the Hadamard gate and NOT gate are introduced as matrices that rotate qubit states. The document explains that two qubits can be represented as a four-dimensional vector and describes how gates like CNOT operate on multi-qubit states. In summary, the document introduces the basic mathematical concepts underlying quantum computing including qubit states, gates as rotations, and representations of multi-qubit systems.

![SWAP gate

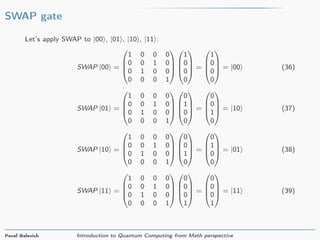

What if we apply CNOT, flipped CNOT and CNOT consequently?

Figure: SWAP circuit [I. Chuang(2004b)]

SWAP =

1 0 0 0

0 1 0 0

0 0 0 1

0 0 1 0

1 0 0 0

0 0 0 1

0 0 1 0

0 1 0 0

1 0 0 0

0 1 0 0

0 0 0 1

0 0 1 0

=

1 0 0 0

0 0 1 0

0 1 0 0

0 0 0 1

(35)

Pavel Belevich Introduction to Quantum Computing from Math perspective](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introductiontoquantumcomputingfrommathperspective-180328145845/85/Introduction-to-Quantum-Computing-from-Math-perspective-19-320.jpg)

![Creating Bell state

Consider two qubits and let’s apply H to the first and CNOT to both:

Figure: EPR Creation [I. Chuang(2004a)]

CNOT(H ⊗ I) |00 =

1 0 0 0

0 1 0 0

0 0 0 1

0 0 1 0

1

√

2

1 1

1 −1

⊗

1 0

0 1

1

0

0

0

=

1

√

2

1 0 0 0

0 1 0 0

0 0 0 1

0 0 1 0

1 0 1 0

0 1 0 1

1 0 −1 0

0 1 0 −1

1

0

0

0

=

1

√

2

1

0

0

1

=

1

√

2

1

0

0

0

+

0

0

0

1

=

1

√

2

(|00 + |11 )

Pavel Belevich Introduction to Quantum Computing from Math perspective](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/introductiontoquantumcomputingfrommathperspective-180328145845/85/Introduction-to-Quantum-Computing-from-Math-perspective-21-320.jpg)