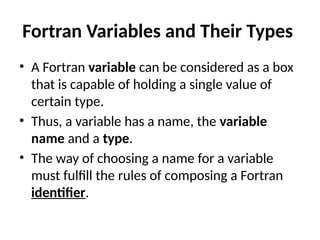

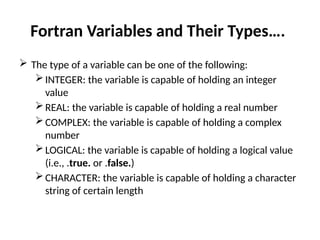

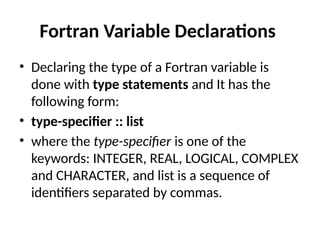

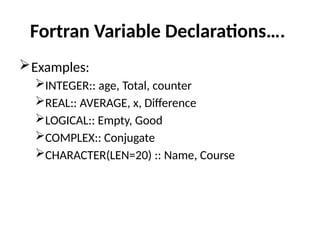

The document outlines the syllabus for a course on Object-Oriented Fortran Programming at Ahmadu Bello University, covering essential computer science topics such as computer systems, programming languages, and specific details about Fortran programming. Key elements discussed include computer hardware and software, Fortran program structure, constants, variables, and the categorization of programming languages. It emphasizes the importance of proper variable declaration and initialization, providing examples of different data types and their properties.

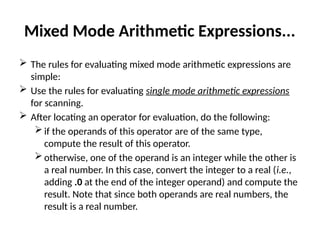

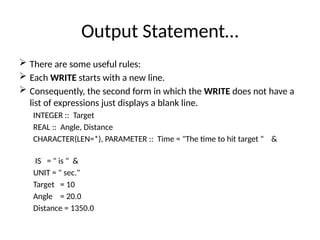

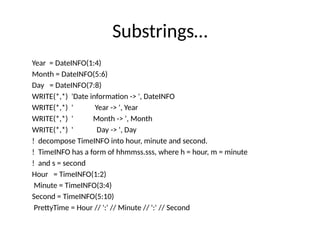

![F90 Program Structure

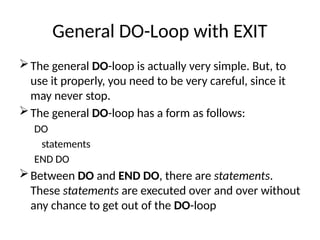

• A Fortran 90 program has the following form:

PROGRAM program-name

IMPLICIT NONE

[specification-part]

[execution-part]

[subprogram-part]

END PROGRAM program-name](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cosc344-240910141126-9c004e76/85/introduction-to-FORTRAN-programming-for-ABU-students-17-320.jpg)

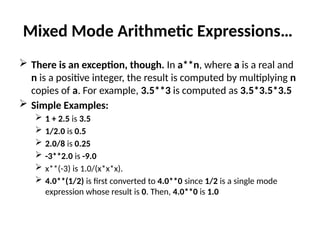

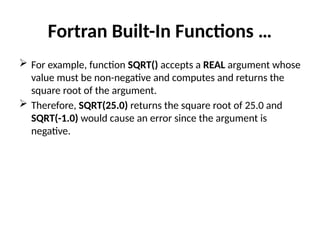

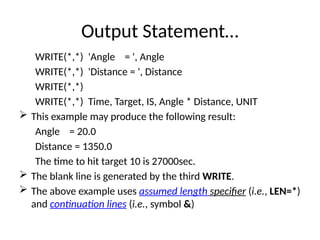

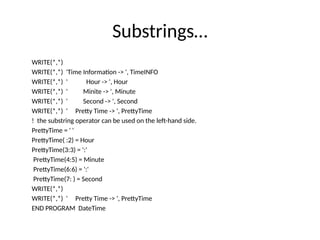

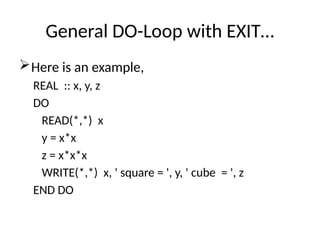

![Mathematical functions…

Note that all trigonometric functions use radian rather than

degree for measuring angles.

For function ATAN(x), x must be in (-PI/2, PI/2).

For ASIN(x) and ACOS(x), x must be in [-1,1].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cosc344-240910141126-9c004e76/85/introduction-to-FORTRAN-programming-for-ABU-students-64-320.jpg)

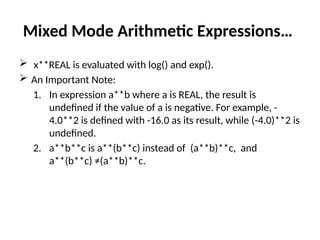

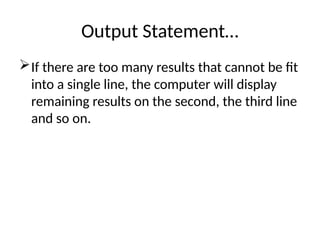

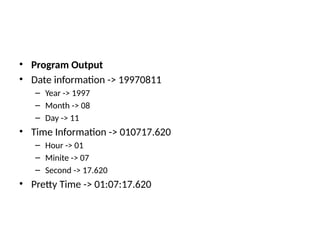

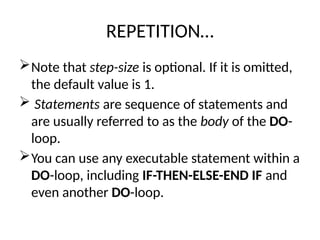

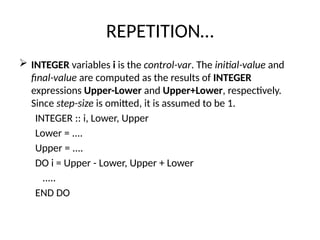

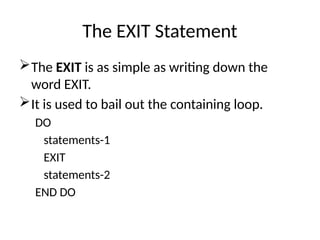

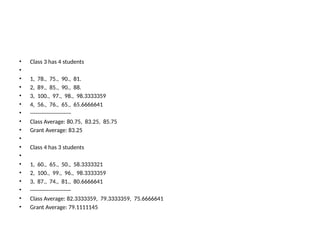

![REPETITION

There are two forms of loops:

the counting loop

the general loop.

The syntax of the counting loop is the following:

DO control-var = initial-value, final-value, [step-size]

statements

END DO

• where :

– control-var is an INTEGER variable,

– initial-value and final-value are two INTEGER expressions,

– and step-size is also an INTEGER expression whose value cannot be

zero.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cosc344-240910141126-9c004e76/85/introduction-to-FORTRAN-programming-for-ABU-students-120-320.jpg)

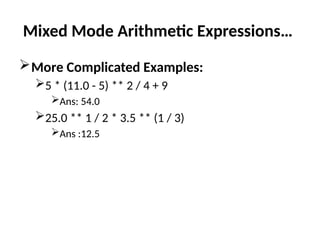

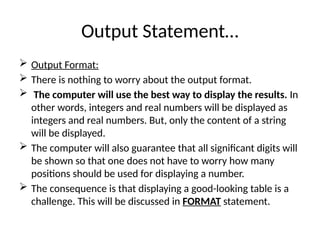

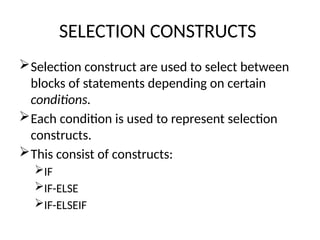

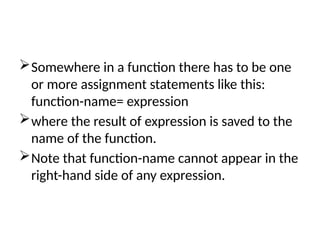

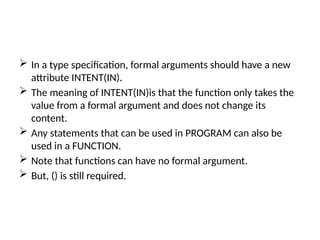

![Type FUNCTION function-name(arg1, arg2, ..., argn)

IMPLICIT NONE

[specification part]

[execution part]

[subprogram part]

END FUNCTION function-name

Type is a Fortran 90 type (e.g., INTEGER, REAL,LOGICAL,

etc.) with or without KIND.

function-name is a Fortran 90 identifier zarg1, …, argn are

formal arguments.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cosc344-240910141126-9c004e76/85/introduction-to-FORTRAN-programming-for-ABU-students-158-320.jpg)

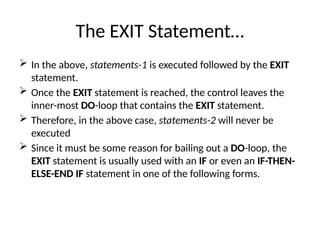

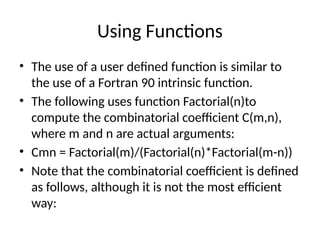

![Where Do Functions Go:

Fortran 90 functions can be internal or external.

Internal functions are inside of a PROGRAM, the

main program:

PROGRAM program-name

IMPLICIT NONE

[specification part]

[execution part]

CONTAINS

[functions]

END PROGRAM program-name](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cosc344-240910141126-9c004e76/85/introduction-to-FORTRAN-programming-for-ABU-students-163-320.jpg)