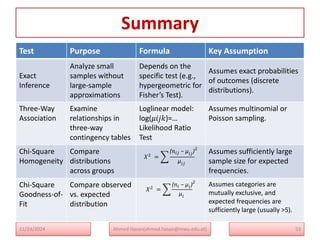

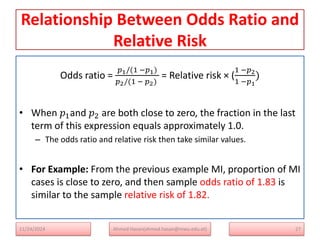

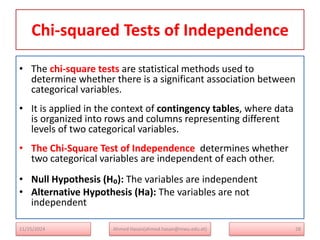

The document serves as a lecture note on categorical data analysis, focusing on contingency tables and their components, including probability structures, analysis methods, and measures of association. Key topics include chi-square tests for independence, relative risk, and odds ratios, along with their applications in comparing categorical data. The content emphasizes the importance of understanding relationships between categorical variables through various statistical approaches.

![Inference for Odds Ratios and Log

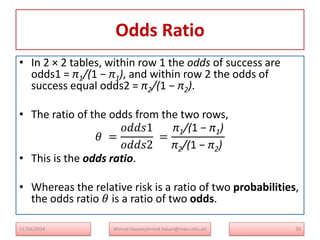

Odds Ratios

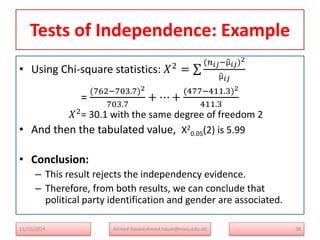

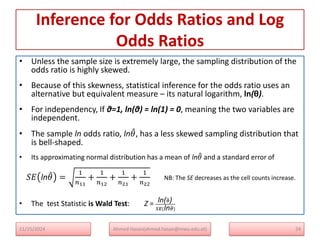

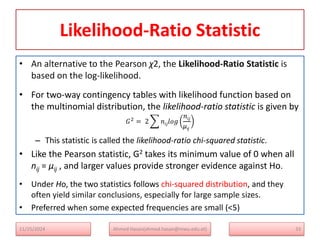

• For the population, a 95% confidence interval for lnθ equals

0.605 ± 1.96(0.123), or (0.365, 0.846).

• Back-transform to odds ratio scale: The corresponding confidence interval

for θ is

(e0.365, e0.846) = (1.44, 2.33)

• This is from the equality of ex = c is equivalent to ln(c) = x

– For instance, e0 = exp(0) = 1 corresponds to ln(1) = 0; similarly, e0.7 =

exp(0.7) = 2.0 corresponds to ln(2) = 0.7]

• Since the 95% confidence interval (1.44, 2.33) for the odds ratio does not

contain 1.0, the true odds of MI seem different for the two groups.

• We estimate that the odds of MI are at least 44% higher for subjects

taking placebo than for subjects taking aspirin.

26

Ahmed Hasan(ahmed.hasan@mwu.edu.et)

11/25/2024](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-241208081723-f1370246/85/Introduction-to-Categorical-Data-Analysis-Contingency-Table-26-320.jpg)

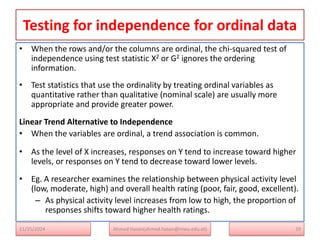

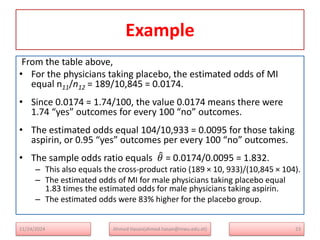

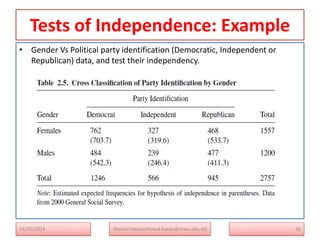

![Tests of Independence: Example

• Ho: political party identification and gender are Independent

Using likelihood test: G2 = 2 nij 𝒍𝒐𝒈

nij

µij

• The expected frequency, µij =

𝑛𝑖+𝑛+𝑗

𝑛

µ11 =

𝑛1+𝑛+1

𝑛

= µ11 =

1246∗1557

2757

= 703.

µ12 =

𝑛1+𝑛+2

𝑛

= µ11 =

1557∗566

2757

= 319.6

……..

µ23 =

𝑛2+𝑛+3

𝑛

= µ23 =

1200∗945

2757

= 411.3

• Now, G2 = 2[762 log

762

703.7

+…+477 log

477

411.3

] = 30

• with (I-1)(J-1) =2 degree of freedom

37

Ahmed Hasan(ahmed.hasan@mwu.edu.et)

11/25/2024](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch-241208081723-f1370246/85/Introduction-to-Categorical-Data-Analysis-Contingency-Table-37-320.jpg)